There are ordeals that reveal a nation unto itself. That is the case for those who live in France since the terrorist attacks in Paris on January 7th, 8th and 9th. Will we be able to recognise this France such as it is, such as it works and lives, such as it suffers, such as it dreams and invents itself, such as it straightens itself up and rallies together? Or will we continue to ignore it by denigrating and depreciating it, by lowering it, making it panic by leading it onto this self-hate fuelled by unfortunate questions of identity, of a ‘French suicide’ and by fantasies of submission in which macerate bitterness and resentment?

The true face of France is that of those who died during those three days of attacks upon our freedom. Three days of crimes, beginning with the attack upon Charlie Hebdo magazine, followed by the executions of police officers and the murders of Jews. It was the assassination of the right to live, to think and to express oneself in security, within the diversity of our opinions and our origins and of our convictions and our beliefs. Christians, Jews, Muslims, freemasons, atheists, agnostics, from here and elsewhere, those who were killed by the terrorists are the very image of our country, one which is diverse, multicultural and multi-faith, from near and far. A nation nourished by its constant interaction with the world, where these identities knitted by relations, exchanges and sharing are invented and are the foundation of common causes.

In its ordeal, France showed that face, free of frontiers and barriers. That of the words of the Internationale, the song of Parisian proletarians which, after having for so long circled the world, was sung to accompany the coffin of Charlie Hebdo editor Charb, during his funeral in the town of Pontoise: “The human race... There are no supreme saviours… let us save ourselves… Decree the common salvation... The earth belongs only to men... Equality wants other laws” Humanity as a common demand, without distinctions of origins, appearance or belief, in mutual respect of our heritage and belonging.

It was a sign of destiny for he who, in a murderous moment, was the true portrait of France - generous and courageous, hard-working and audacious – yet was not of French nationality, (before gaining it since by the miracle of his actions). ‘He’ is Lassana Bathily, the young man who saved hostages in the kosher supermarket after it was attacked by one of the gunmen on January 9th. Of Malian origin and Muslim faith, a black immigrant worker who was until recently threatened with deportation, he is now a French citizen with all his rights. It was as if the world had suddenly come to our aid. That world which, for centuries, has made France, which shapes its people, which contributes to its wealth.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

A Muslim hero. Two other people, one of Muslim faith, the other of Muslim origins, were among the victims of the two gunmen who attacked the offices Charlie Hebdo – a policeman and a copy editor. Two guardians, one could say, one an officer of the peace and the other of language – of the French language and of French peace. If I underline this, it is naturally not to distinguish them from the other victims, but simply to set out this plain truth: Islam belongs to France. That was similarly the message of German Chancellor Angela Merkel regarding Germany, when she spoke on the issue of the racist demonstrations in that country which call for a Europe without Muslims, the amputation of a part of itself, a section of its humanity removed.

This truth must, more than ever, be said. For while it has already been shaken, now it is threatened. Firstly by the terrorists – those three assassins armed by a murderous and delirious ideology - who are always at the service of politics of the worst kind. By the weight of their crimes carried out in the name of Islam but which they betray and deface, caricaturing it in a more savage and painful manner than any inoffensive and innocent caricature on paper could. In sum, they threaten this truth by the negation of their own humanity as signified by their cold, premeditated murder of other human beings because of their ideas, origins and beliefs.

In face of their acts, for which they are accountable and for which they paid with their lives, one is reminded of the observation of French writer, essayist and poet Charles Peguy (1873-1914), a committed Christian and republican, writing about religious sectarians, whoever they may be. “Since they don't have the courage of being from the world, they believe that they are of god,” he wrote. “Since they don't have the courage of being one of the parts of mankind, they believe they are one belonging to god. Since they are not of mankind, they believe they are of god. Since they don't love anybody, they believe that they love god.” Péguy invited these sectarians to remember that “Jesus Christ was of man”, as might also be said of Moses or Muhammad.

A world heading for a brick wall

“It suffices not to lower the temporal in order to raise oneself into the category of the eternal,” wrote Péguy in his inimitable style that joins prose with homily. “It does not suffice to lower the world to rise into the category of god…No-one will be diminished so that others appear greater”. Those lines were written just weeks before Péguy was killed on September 5th 1914 in Europe’s blind rush to war, the continent sinking into an endless conflict of nations and civilizations and on to the final barbarity of crimes against humanity. While in 2014, during the centenary commemorations of World War One, we recalled with lucidity this tragic mistake, the disastrous sacred unions and lying propaganda, will we know how to avoid its repetition, between East and West?

Put thus, the question is not alarmist but simply lucid. The contexts might well be different, but we know from recent experience in the world the trap into which we are invited. It is that of the politics of fear which, turning a blind eye to the causes and targeting the effects, only increase the peril and threat. That was the dramatic mistake made in the US, after the September 11th 2001 terror attacks in the country, and for which we are today paying the price. It was not only the emblematic moral discredit brought upon a democracy, which attacked its own freedoms and fundamental human rights to the point of allowing torture, but above all the invasion of Iraq, which offered, in the murderous decomposition of the country and its institutions, a new breeding ground for totalitarian ideologies for which Islamic State is now the flag.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

To warn ourselves to this is to demonstrate concern about France, its security and its wellbeing. In face of disorders born from injustice and misery, resentment and humiliation, lightweight politicians rush to a short-cut of security and authoritarian measures, eager to proclaim that they will bring an end to the troubles, even if at the price of new injustices. They are short-sighted and short-term, solving nothing fundamental, and building only provisional protection behind which – the same causes producing the same effects – the enemies of democracy and freedom will find new arguments and new recruits.

On the opposite, responsible politicians will always seek to identify the injustice which is the cause of the disorder, to think about it, to reduce it and to solve it. To have a true concern about the security of one’s people and, wider still, humanity, is to follow this approach, in both depth and duration. It is to take the risk of inviting reflection beyond emotion and, consequently, to understand that this totalitarian violence which hit us will not only not cease but will become worse if we do not meet the challenge that is thrown down to us: affront the injustices, inequalities, miseries and humiliations that produced it, whether at a worldwide level or that of our country.

A world which accepts that the richest 1% of the global population will soon own more than half of international wealth is heading for a brick wall, where lies endless violence, beyond frontiers and territories, as is the new shape of war. The first to know this, for they have for so long suffered because of it, are the peoples of the Arab world, who are predominantly of Muslim culture. Peoples who are so enduringly confronted with corrupt regimes which are indifferent to misery and poverty and which offer no horizon of hope to the young, thus leaving free reign to terrorism. How can we not question our responsibility in France for this impasse when, in 2014, our own state congratulated itself for the steep rise in French weapons sales, for which the principal client is the obscurantist religious kingdom of Saudi Arabia?

But despair is not only found far away, and we can no longer pretend to ignore it, turning our gaze away from the misery on our streets, on our pavements, or simply never seeing the poverty relegated to what an official vulgate calls “neighbourhoods”, in reference to the low-income urban zones. Must we have become so blind to ourselves for it to be so difficult to stare this reality in the face? Just like their predecessors who committed anti-Semitic crimes in Toulouse and in Brussels, the three terrorists involved in the attacks during this dark January of 2015 are children of our society, of our nation, of our republic. Born French, they had not come from elsewhere, they came from here.

These assassins are from our people. To remind ourselves of this is in no way to excuse their acts, but simply to be republican, truly republican, not in a posturing manner but in a demanding one. Republican as was the celebrated French 19th-century writer Victor Hugo. In 1849, after his election to the French parliament and conscious of the urgency of addressing issues of social misery, he gave a speech before the house in which he scolded his conservative colleagues: “How can one want to cure the ill if one does not examine the wounds?” he asked them. “You have done nothing, as long as the spirit of revolution has public sufferance as its aide. You have done nothing, nothing, as long as in this work of destruction and darkness, which continues underground, the nasty man has as his collaborator the unhappy man.” Hugo ended with the warning: “Gentlemen, think about it,it is anarchy that opens up the abyss, but it is misery that digs it.”

Hate cannot be given the excuse of humour

Resentment is a sour force in History. It is made of unhealed wounds, of ineffaceable affronts, of violence suffered, accumulated humiliations, distant traumatisms that leave a heavy heritage. In sum, a sufferance and a necrosis of hope, leading to the sentiment of being at a total impasse, with an impossible and unthinkable future. At that stage, resentment destroys the value of politics as a common good. Those who succumb to wallowing in victimisation ceaselessly look for scapegoats for their despair. Their grievance runs up against so many walls that they only imagine escaping from the situation through destruction, to the point of openly denying the humanity that they have not been given. This is made all the easier by our interconnected world, with its reduced space and immediacy, which offers them via computers a nihilistic ideology that fills this existential vacuum.

We in France have never stopped fuelling this resentment among a section of our people, of our young. That section which, on a daily basis, does not live out the ‘republic for all’. A section which, for decades, has been reductively looked upon with regard to its origins, its appearance, its culture, its religion, as if it was apart from the rest, kept to one side and at a cautious distance. This section comes from France’s long projection abroad and which has circled back to the ‘America’ of Europe that our country represents, a country in which the working classes have always been renewed by waves and mixtures of migration. It is a section of our people whose legitimate democratic and social expectations have so often been dismissed on the basis of ethnicity or religious pretexts.

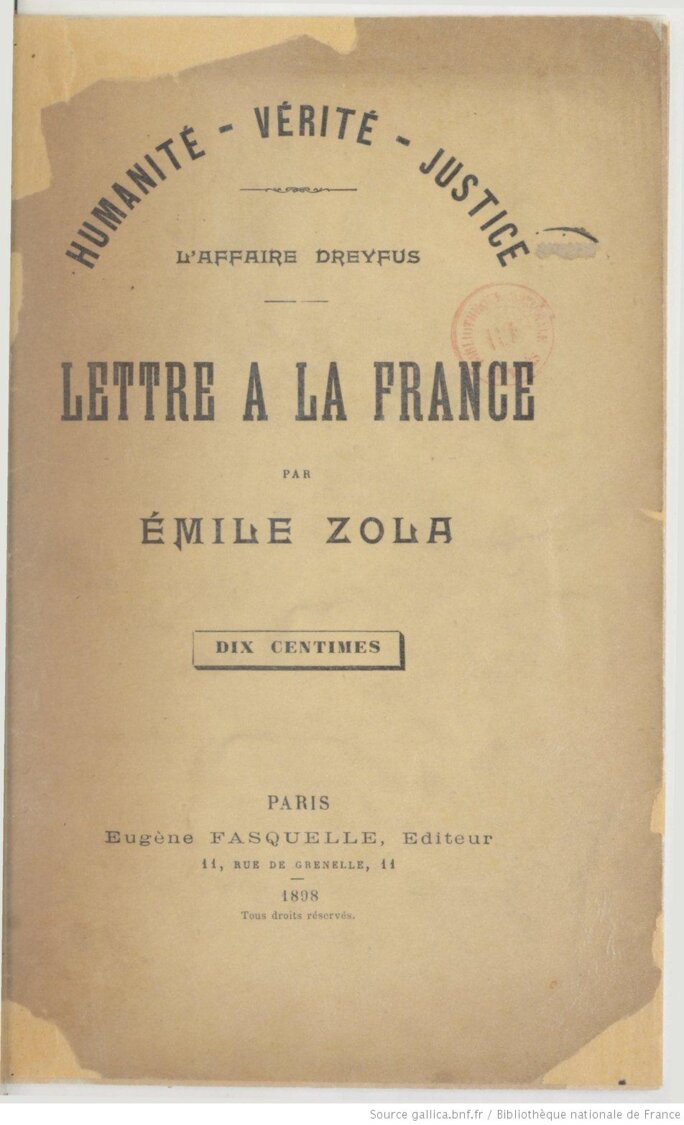

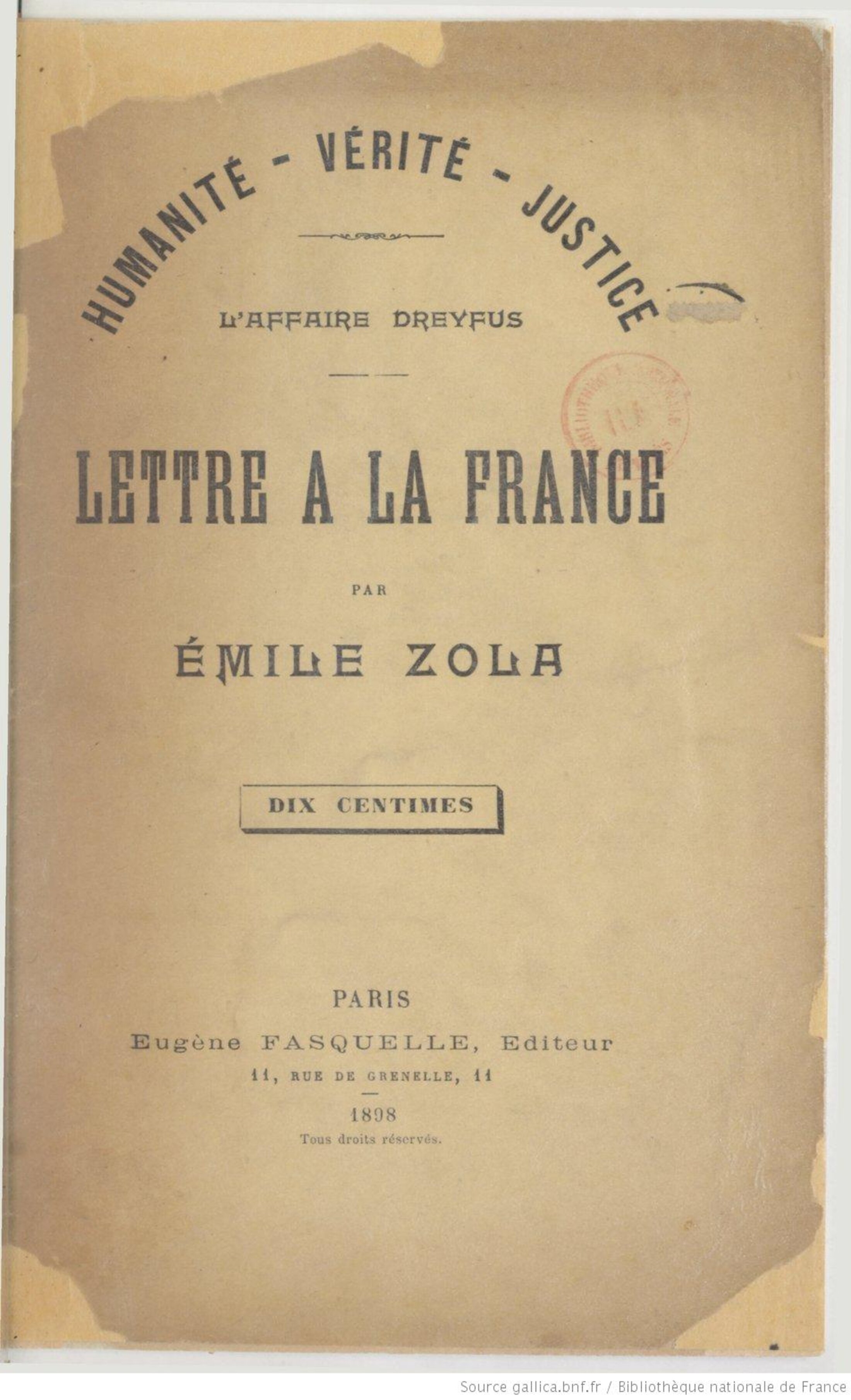

That was the sense of the alarm I raised in my book published in France in September last year entitled Pour les musulmans (For the Muslims). The book was a prolongation of another I published last spring, Dire non (To say no), an appeal to say ‘no’ to the monsters that are racism and xenophobia, hate and violence, the morbid phenomena of times of transition and uncertainty, when the old world dies and the new one is late coming. “By regularly waving a scarecrow at the people, one creates the true monster”: In writing one alert after another, I have never ceased citing this quote from French writer Émile Zola (1840-1902), taken from his 1896 book Pour les juifs (For the Jews) which was my departure point. It was in vain, alas, because the media and editorial landscape was, until the terror attacks this January, full of Islamophobic scenarios which designated our Muslim compatriots, across their diversity of origins, culture and beliefs, as trouble-makers, as devious and threatening invaders for whom deportation from our country, theirs, should be envisaged.

How can we teach our young simple civility, to respect the other, to not insult and offend someone because of their origins, appearance of faith if the media and politicians adopt the reverse approach? One that is an irresponsible transgression, destructive of every ideal of solidarity, of a common republic, of any national community. The proclamation of freedom of expression, the defence of the right to caricature, with its ironic or mocking excesses, and which have accompanied the demonstration of solidarity with Charlie Hebdo, does not imply that our public life must lower and lose itself in the detestation of a section of our people for reasons of its origins, culture or religion. Hate cannot be given the excuse that is that of humour.

Pour les musulmans could just as well have been entitled Pour la France (for France). For it is an appeal for common causes, for an awakening of society so that all of this republic be at last for everyone, to take this path of empathy upon which, in walking towards the other, one finds oneself. To look together for that democratic and social horizon which, alone, can leave behind the clouds and storms that threaten. To rally together and to collectively support the demands of equality, that equality of rights and possibilities that the obsession with identity seeks to ruin, allowing the ravages of inequalities, hierarchies and exclusions.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

“France, wake up, think of your glory,” wrote Emile Zola in his 1898 work, Lettre à la France (A Letter to France), from which I have extracted this warning: “The republic is invaded by reactionaries of all types, they love it with a sudden and terrible love, they embrace it to suffocate it.” For the author of the celebrated denunciation of the injustice of the Dreyfuss affair, J’accuse… !, could only imagine the French republic as one in motion, invention and creation, at the opposite of the immobilisation and conservatism which, too often, claims right to the name of the republic while cautioning rejection and feeding fear.

Zola, the son of an Italian immigrant, addressed his country thus: “Is that what you want, France, the placing in peril of all that you have so dearly paid for, religious tolerance, equal justice for all, the fraternal solidarity of all citizens?”

France, more than a century later, I ask you the same question.

-------------------------

- The original French text of this op-ed can be found here.