Confidential documents seen by Mediapart highlight the financial plight of some of France's top-flight professional football clubs as a result of the Coronavirus pandemic. In particular, clubs in the top echelons of the French game, Ligue 1 and Ligue 2, have felt the full effects of the abrupt end of the 2019-2020 season on March 13th because of the virus.

The shutdown meant a halt to televised rights payments from broadcasters Canal+ and beIN Sports, a loss of turnstile revenue, a collapse in sponsorship deals and a major reduction in the number of transfer deals. But while these income sources dried up the clubs' outgoings, and in particular the huge wage bill of their players, have remained, plunging clubs into unprecedented financial problems.

Officially, the Ligue de Football Professionnel (LFP), the body which oversees Ligue 1 and Ligue 2, sees the problem as temporary turbulence. At its general assembly, held by videoconference on Wednesday May 20th, which led to a brief press statement, LFP members voted for a resolution authorising its director general Didier Quillot to take out a state-guaranteed loan of 224.5 million euros. This figure corresponds to the broadcast rights money that clubs have not yet received for the remainder of the current season. The hope is that this sum will enable clubs to be on a sound footing when the new season is able to get under way. There was little dissent and the resolution was backed by almost 70% of the vote. The only ripple of controversy was when Olympique de Marseille's president Jacques-Henri Eyraud, who was in a row with a counterpart from L2, pointed out that Mediapart was about to publish an investigation into the issue.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

However, confidential LFP documents that were drawn up to prepare for the general assembly, and which Mediapart can now reveal, contradict this superficial optimism. They show that professional football's financial crisis is a lot worse that has been stated, to the point that several Ligue 1 clubs are on the brink of going into to administration - Olympique de Marseille, Girondins de Bordeaux, AS Saint-Étienne and LOSC de Lille seem the most at risk.

One cannot even rule out the possibility of the LFP itself getting into serious difficulty and finding it hard to repay the huge loan that it has just taken on. The inevitable consequences of this would be that, after years of crazy ever-higher broadcast rights money to help pay huge salaries to young footballers and to fund transfer fees that are just as exorbitant, the French taxpayers would have to foot the bill for these football industry excesses.

To understand the risk that the LFP is taking by agreeing to this loan – and the French state, too, in guaranteeing 90% of it – we need to go back a year. For even in 2019, before the virus crisis, many football clubs were in a very difficult financial situation because of the direction the football indsutry has been taking.

The official figures published for the 2018-2019 season by the body which oversees the accounts of professional football clubs, the Direction Nationale du Contrôle de Gestion (DNCG), give an idea of the picture. In that year L1 and L2 clubs had combined net losses of 160 million euros, with 126 million euros for L1 clubs alone. In L1 Olympique de Marseille (OM) had a deficit of 91 million euros, while Lille were 66 million euros in the red and Bordeaux 25.7 million euros.

As a backdrop to the crazy situation Ligue 1 now finds itself in – having imported all the traits of Anglo-Saxon financial capitalism into the sport – it should be noted that these clubs have had virtually no financial stability in recent years. Yes, football income has been rising through broadcast rights, the transfer market, sponsorship and ticket sales, but the costs have gone up just as much, starting with huge player salaries. Trapped inside this ever-expanding bubble, the clubs have nearly always been in deficit.

Professional football's mad descent into the world of financial capitalism

Yet at the end of the 2018-2019 season many Ligue 1 clubs believed that matters would improve, notwithstanding the 126 million-euro deficit. In February 2020 the sports newspaper L'Équipe summed up the way the clubs saw things: “The clubs look forward to the start of the new broadcast deals. It is known that for the period 2020 to 2024 Mediapro [editor's note, the Spanish multimedia company] has bought most of the rights to Ligue 1 matches with the promise of an annual cheque of 780 million euros (to which one must add 330 million euros from beIN Sports and 50 million euros from Free to reach a record total of 1.153 billion euros) and a good number of Ligue 2 matches for a cost (with beIN Sports) of 64 million euros a year. That represents a rise of almost 60% compared with the current sums. And even more for some.”

So at a difficult time financially, struggling L1 and L2 clubs were awaiting salvation in the form of a further increase in broadcast rights income. Yet the clubs are now at risk of losing out on this gamble because of the coronavirus crisis. It is one of the features of speculative bubbles that they can collapse at any time. That is what has happened with the Covid-19 crisis: at a stroke the ground has been taken from under the feet of the Ligue 1 clubs.

So rather than bouncing back, most of the clubs have fallen into a bottomless pit; the short-term virus crisis has revealed the longer-term structural crisis of the football industry.

The mechanics of how football arrived in this situation are straightforward. The game's income has been constantly rising in recent years. But everything changed on March 13th when because of the Covid-19 epidemic, professional football was abruptly stopped and the clubs' entire income virtually dried up overnight.

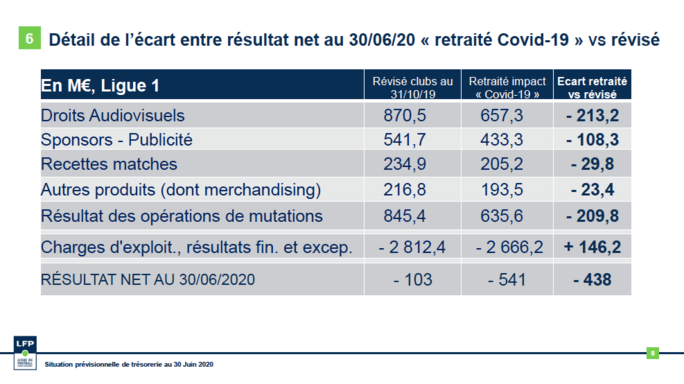

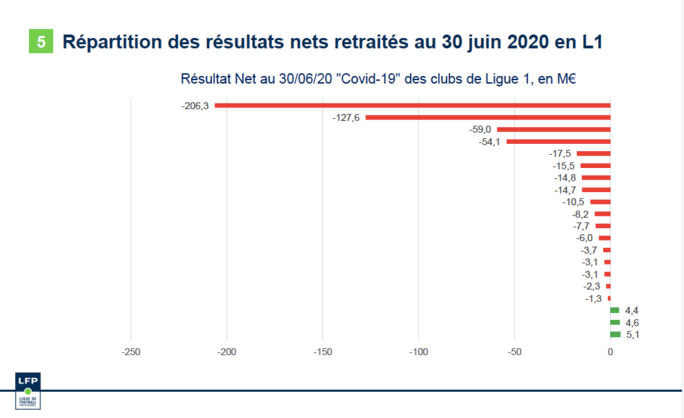

Canal + stopped paying the broadcast rights money that was due to run until the end of the year; ticket receipts ended immediately; and income from transfers dropped massively. As a result the total deficit forecast to be caused by the Covid-19 crisis for L1 clubs by the end of June was 438 million euros, as the table below from the confidential LFP documents shows.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

This table shows that the unpaid broadcast rights total 213.2 million euros, marketing income will be down by 108.3 million euros and transfer income will have tumbled by 209.8 million euros.

It was against this backdrop that the LFP's board of directors started thinking about taking out a state-guaranteed loan for 224.5 million euros to at least compensate clubs for the unpaid broadcast rights income. This was the project that came to fruition on Wednesday May 20th, and the vote by the LFP's general assembly, details of which can be seen on page 10 of the document below.

The go-ahead from the French Treasury

However, this loan is set to cause as many problems as it resolves, if not more.

On page 3 of the document the LFP states the aim of the loan deal as follows: “Money earmarked to meet the needs of the LFP's cash flow to deal with the financial consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic; the money will be used to preserve activity and employment in France.”

This explanation appears curious; by using the pretext of saving employment the LFP presents itself as a normal company, even though this is about saving the football business industry, including its financial excesses.

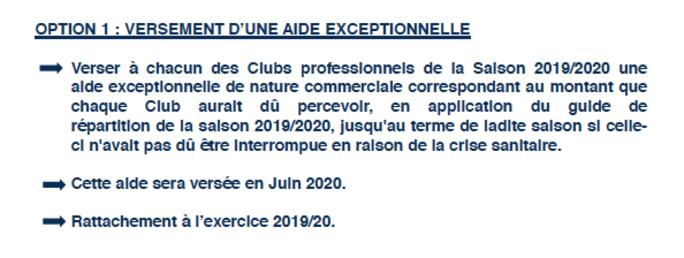

The document gives more details about the use that will be made of the state-guaranteed loan: “To give each of the professional clubs for the 2019-2020 season a one-off payment of a commercial nature corresponding to the sum the club would have received by the end of the season, by applying the distribution breakdown [of money] for the 2019/2020 season, if it had not had to be interrupted because of the health crisis.”

The way the loan is presented here is thus very clear. But the reality is more complex. First of all, in most cases French companies who ask for these loans – known as PGEs for prêt garanti par l’État – are those which are in financial difficulties. “A company whose finances are impacted by the coronavirus-Covid-19 epidemic can ask for a state-guaranteed loan, whatever its size and status. This aid is applicable until December 31st 2020,” explains the government site Service Public, which summarises the major decisions made by the public authorities.

The LFP clearly does not come into this category as it is not its own finances that have been hit by the health crisis, but those of the L1 and L2 clubs which it represents. So is the LFP legally allowed to take out a state-guaranteed loan? There is another issue, too; while the LFP has sought a loan on behalf of the clubs, ten of them have also applied for their own state loans.

These clubs can do this legally as long as the total amount of the loans they receive does not exceed 25% of their turnover. During an earlier general assembly on May 4th the chairman of L1 club Olympique Lyonnais, Jean-Michel Aulas, was worried about the overlap between the loan taken out by the LFP and those taken directly by the ten clubs.

On May 6th the LFP's Didier Quillot replied to his concerns by email: “I have received from the CIRI [editor's note, the Comité Interministériel de Restructuration Industrielle, a body under the control of the French Treasury] which looks after the management of the PGEs [state loans] inside the Ministry of Finance the following confirmation: 'The procurement by the Ligue of a state-guaranteed loan will not have an impact on the eligibility of the clubs who could also ask for a loan, as long as the clubs each respect the criteria laid out in the law to benefit from these loans (which will be assessed on a case by case basis by the banks'.”

This fairly vague email does not remove all the uncertainty over the correctness of the procedure chosen. But it is absolutely clear on one point: the whole set-up was cleared at high level by the Ministry of Finance.

Some observers insist that the arrangement was very straightforward, and that the LFP's finance director went to the Société Générale bank's branch at Neuilly-sur-Seine, west of Paris, and it was here that the state-guaranteed loan deal was put together. But the state does not guarantee a loan of 224.5 million euros without the matter being passed up to the minister of finance's desk, and probably not without the minister – currently Bruno Le Maire - then referring the issue to the Élysée.

The key point here is that the state agreed to a relatively complex arrangement which puts the burden of risks of the loan on the LFP.

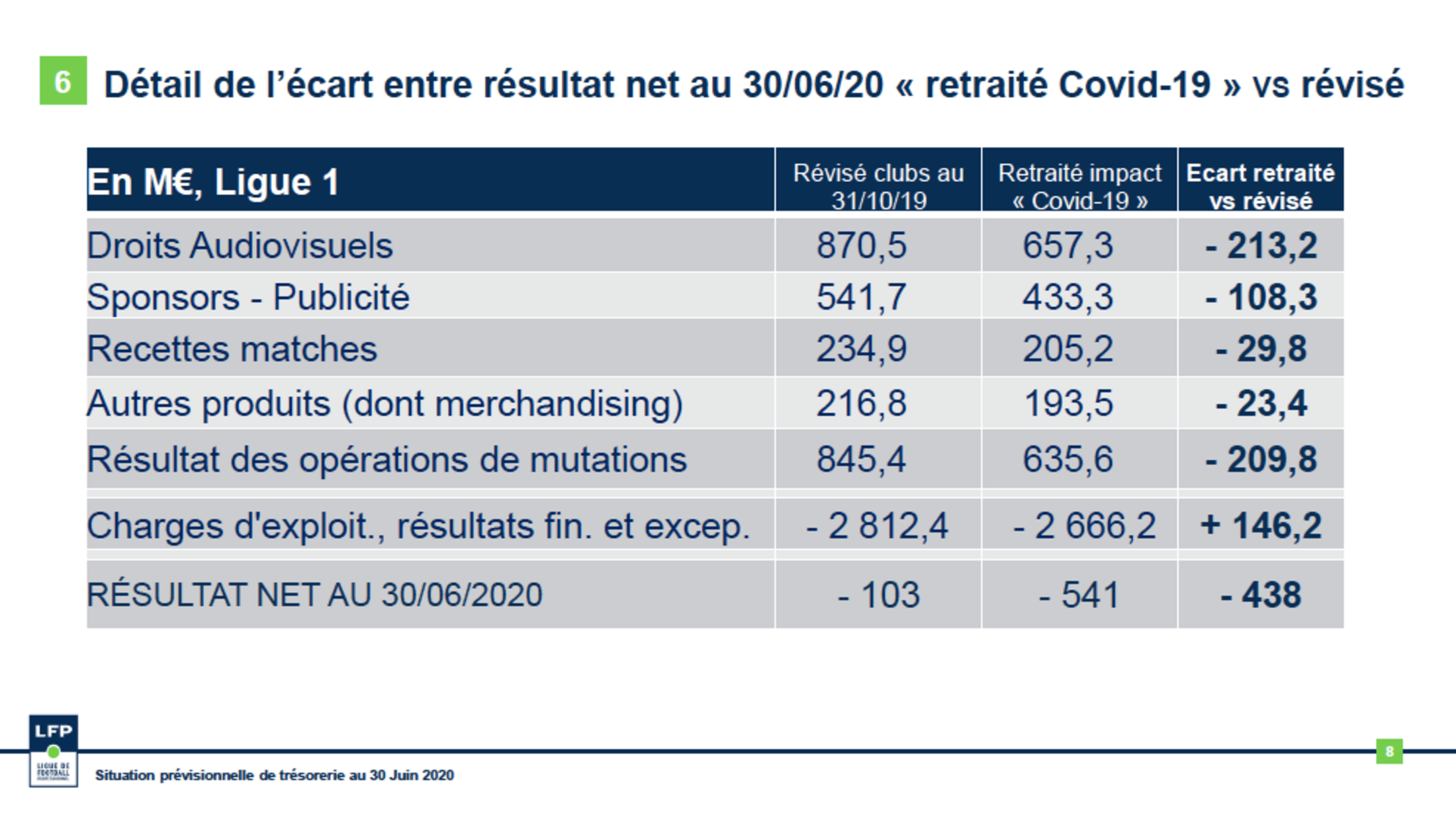

So what will the effects be of this state-guaranteed loan? The clubs from Ligue 1 and, to a much lesser extent, Ligue 2 are thus going to receive in June what they will have lost in broadcast rights because of the abrupt end to the season. The LFP has not stated publicly how the money from the loan will be shared out, but it is revealed in the organization's internal documents, in particular the one below.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

We can see here that the rationale behind the division of the loan is to compensate the clubs on a pro rata basis for the money they would have got from the broadcast rights. Priority is not being given to clubs who are most in difficulty, even if among those clubs who will get the most from the loan there are some who are also in great need. Moreover, the money will be divided out very unequally as the first seven clubs who appear in the table are going to get a large slice of the loan total.

In any case, it is a very odd kind of state-guaranteed loan as it seeks to save the football business industry as a whole and not individual clubs.

Marseille, Bordeaux, Saint-Étienne and Lille in trouble

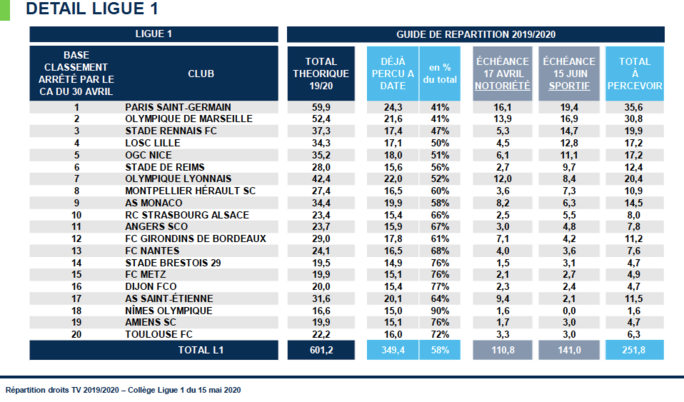

But the greatest concern is that this loan might not in fact be big enough to save some big clubs from bankruptcy. This comes out very clearly in other confidential LFP documents. In particular, to prepare for its general assembly on May 20th the Ligue performed some financial simulations which set out what the situation would be for L1 clubs after the sharing out of the “one-off” payments from the loan.

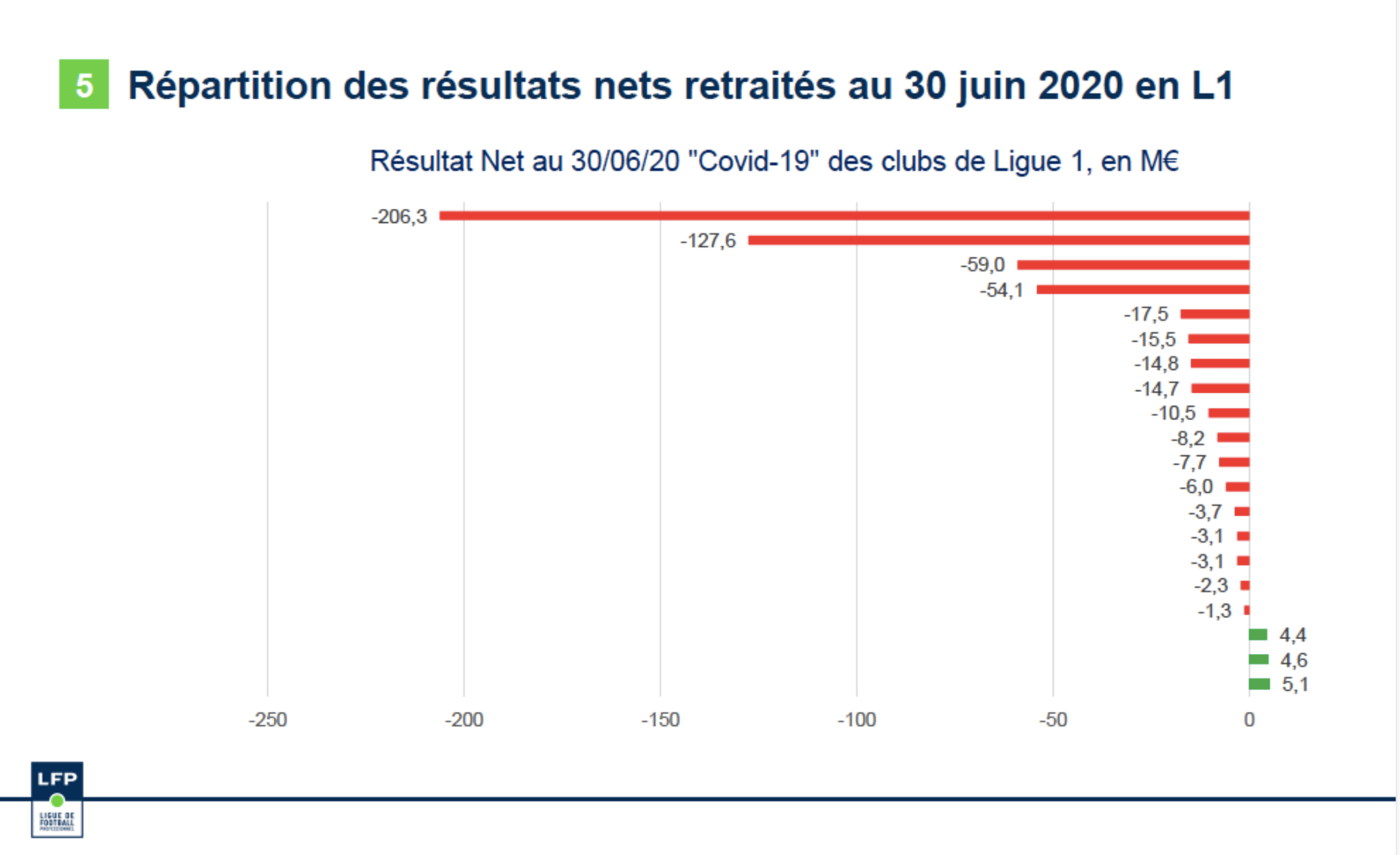

This document reveals that some clubs will still be in an absolutely catastrophic situation. Page 6 sets out what might be the net operating results for Ligue 1 clubs as of June 30th 2020 as a result of the epidemic: and it suggests a net deficit of 541 million euros across all the clubs.On the following page the document sets out the individual situation of each club within this 541 million-euro loss, though anonymously. It shows how some clubs are in a very serious situation. Out of the 20 Ligue 1 clubs just three are forecast to operate at a profit, and these only just, with all the rest in the red. But what catches the attention above all are the huge operating losses of four of these clubs. The first has a deficit of 206.3 million euros, the second 127.6 million, the third 59 million and the fourth 54.1 million euros.

Enlargement : Illustration 9

Can a club survive at that level of deficit? Or is bankruptcy inevitable? On paper one can imagine the shareholders concerned ploughing more money into the clubs. But it could be that some shareholders could have had enough and throw in the towel. That is why one cannot exclude the possibility that this saga will end with some clubs going into administration.

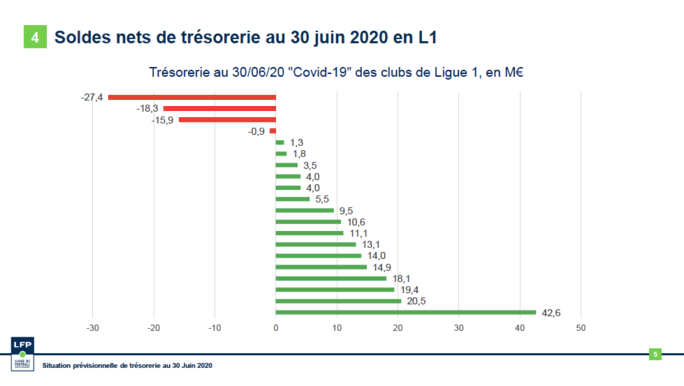

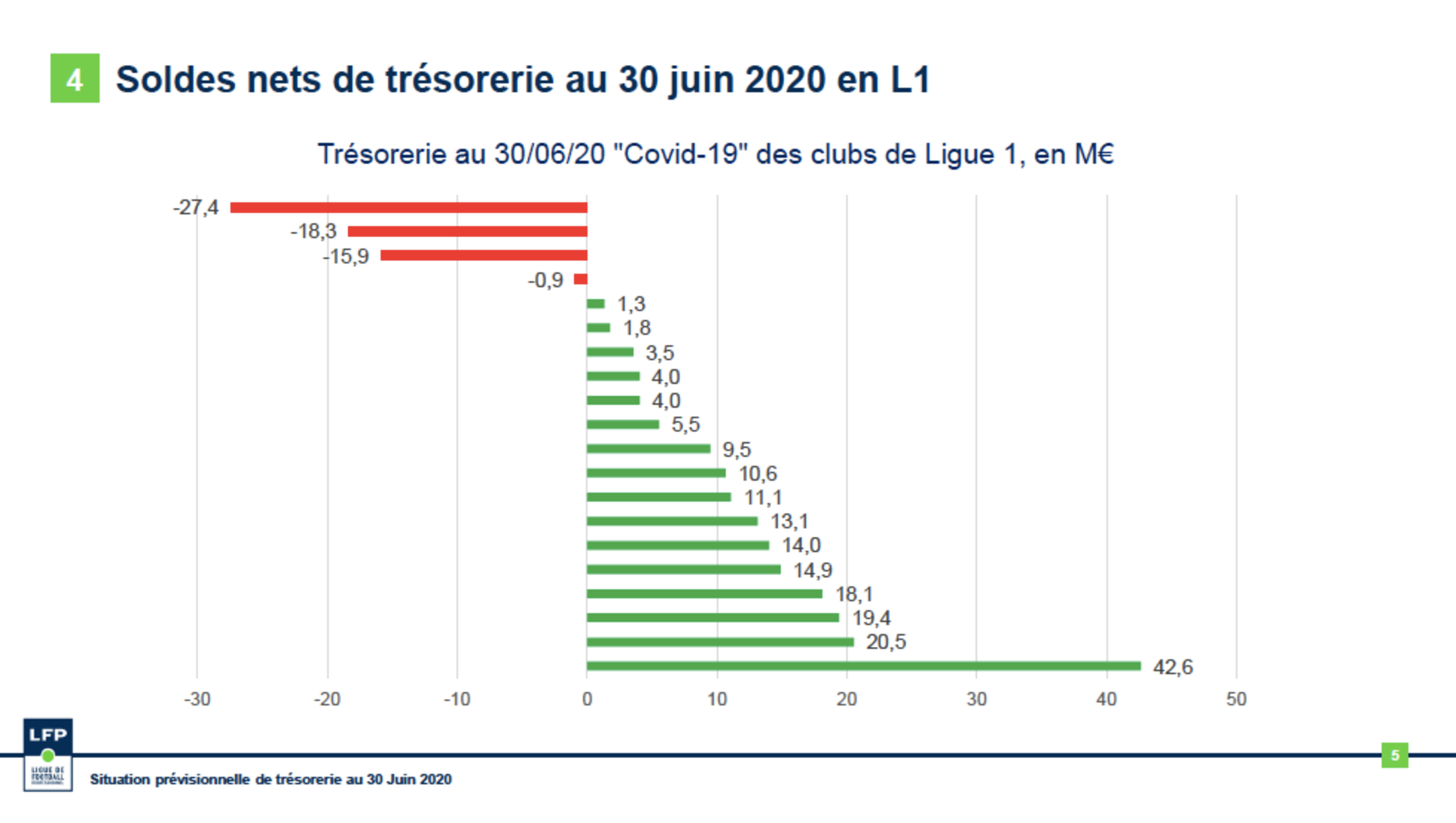

That fear is increased by another confidential LFP document which details what the net cash balance or liquid assets of these clubs will be on June 30th 2020, in other words after the sharing out of the loan money.

Enlargement : Illustration 10

It shows that four clubs – we do not know if they are the same four as mentioned above – will have negative net cash balances close to 60 million euros. One of the clubs will have a negative net cash flow of 27.4 million euros. In others words they are potentially in a situation where they cannot pay their bills.

The body that oversees the club's accounts, the Direction Nationale du Contrôle de Gestion (DNCG), has not carried out an assessment of the latest situation so the LFP refuses to name the clubs in most difficulty. But according to very reliable sources their identity is no great mystery.

One of them could well be Olympique de Marseille (OM), which was already the club with the biggest deficit in the previous season, and could be the club which is set to post a massive loss of 206.3 million euros at the end of June 2020. Alongside OM are Girondins de Bordeaux, AS Saint-Étienne and LOSC de Lille. For some years Lille balanced its books thanks to the sale of some of its players at the end of each season. But this season the great professional football depression will have a major impact on those transfers and the sums they can raise.

The state-guaranteed loan is thus a very risky gamble for these clubs. But it is just as much a risk for the LFP itself, for fairly obvious reasons. It is true that the LFP can argue that it would not be affected by the possible bankruptcy of some clubs, because these clubs do not have to reimburse the amounts they will receive via the Ligue organisation anyway. These payments from the loan have been classified as a “one-off” payment, and are in effect a gift. The Ligue will thus be looking to repay the 224.4 million euro loan by other means.

The repayment plan was part of the resolution adopted by the LFP general assembly on May 20th. It envisages a “business continuity plan and replenishing the LFP's own equity capital over a period of four seasons from the 2020/2021 season, through priority deductions each season of a net sum before tax of at least 67.2 million euros from the broadcast rights which will be paid to the LFP by the L1 and L2 broadcasters, before applying the breakdown of payments and before any distribution to the clubs, which will allow [the LFP] to generate each season a net sum after corporation tax of 55.9 million euros.”

The LFP will thus repay the 224.5 million euro loan over four years by debiting 67.2 million euros each year from the broadcast rights due to the clubs. But this runs the risk of making the crisis last longer. For it means that the clubs themselves will receive less money each year from those broadcast deals. In this way the football business industry bubble is in the process of bursting, to an extent at least. After the euphoria of the deal, the hangover will last a long time.

Even so, it would be wrong to think that the LFP itself is not at risk as well. It is true that in a sense the league organisation is just operating as a form of serving hatch, passing on the loan money from the state to the clubs in the form of huge gifts, and getting repaid from the TV rights each year. However, ultimately it is the LFP that is taking out this huge loan and will be responsible for it, and not the clubs. And that is a huge risk. Back in 2018 the Spanish media group Mediapro beat off Canal+ to become the official broadcasters of Ligues 1 and 2 for the period 2020 to 2024 with a bid of 780 million euros. Yet many people have raised questions about the financial soundness of the Spanish group.

At the time of the bid process the boss of Canal+, Maxime Saada, publicly raised questions about the ability of its rival to “get to the end of the process financially” and to obtain the “necessary value” to pay back its initial stake.

These words can be dismissed as the reaction of a sore loser, but they do highlight that Mediapro's television foray into France, where it aims to pick up 3 million to 3.5 million subscribers, is not an easy one. This threshold of 3.5 million subscribers to fund the purchase of the broadcast rights is very high; the beIN Sports group reached this level at one point only to see its number of subscribers drop spectacularly. That group has continued to record losses since launching in France.

Mediapro could encounter exactly the same problems with one additional handicap; the beIN Sports chain has a state behind it in the form of Qatar, while Mediapro is simply a media group which, like all companies in this sector, has been massively affected by the Coronavirus pandemic. Moreover, the structure it used to bid for the broadcast rights in France was set up on an ad hoc basis, without it being clear exactly what the role of the head company in Spain will be ultimately. That creates some uncertainty.

What would happen if this new player on the French broadcast scene were to go bust? Even though the Spanish group would be able to sub-licence some of its broadcast rights to rivals, such a move could put the LFP in danger.

In the professional football world no one is taking these threats seriously. No one wants to imagine that after the possible bankruptcy of some Ligue 1 clubs, the LFP could itself be at risk of going bust. Yet it is clear from the way the loan has been arranged that it is the LFP that is taking on the debt, and so it must take on the burden of the risks that go with it.

For if Mediapro were unable to meet its obligations, the LFP would be unable to repay this loan debt. At the same time the state's guarantee of that loan would come into play. In such a scenario – which while not certain is indeed possible - French taxpayers would then be asked to pick up the bill to pay off the excesses of the football industry.

What is even more ridiculous about this saga is that though it involves a risky operation, no one – neither the LFP or the state – wanted to put in any safeguards. For example, the LFP could have decided that the money from the loan would only be paid out after the DNCG accounts body had carried out checks on the solvency of the clubs due to receive it. An internal document shows that this option was in fact considered at one point:

Enlargement : Illustration 11

But in the end a different plan was adopted, one which did not involve checks by the DNCG:

As for the French state, there was the same lax approach. What is striking is the ease with which the LFP obtained the state guarantee from the Ministry of Finance. Did officials at the ministry or the Banque Publique d'Investissement investment bank ask questions about the risks they were taking with public money in approving such an arrangement? Reliable sources have told Mediapart that this was not the case and that there were no checks made as to the solvency of the outfits concerned.

The LFP is not the only beneficiary of this behaviour, for the Ministry of Finance is using these state-guaranteed loans to shore up the finances of any company who asks for them, and it is not asking for any commitments in return, either about preserving employment or the use to which the loan money is put.

The Ministry of Finance has in effect opened up a strange new business in which it declares: “Come on in! The money is yours – the risks are ours!” The football industry would have been ill-advised not to have made the most of it.

After the initial publication of this article in French the LFP published a statement in which they “firmly” denied “all the falsehoods relating to the PGE [editor's note, the state-guaranteed loan] contained in this article”.

It continued: “This loan carries no financial risk for the LFP which has adopted, concurrently with the PGE, a repayment plan over 4 years by a deduction at source from the 5.3 billion euros of broadcast income already agreed and to be paid over the 2020/2024 cycle. This sum is made up of combined payments from 4 different broadcasters and not just Mediapro, with the repayments representing no more than 5% of the overall income of the LFP and with no possibility that the French taxpayers will have to contribute.” However, it did not deny any of the information published by Mediapart, which was based on LFP documents.

Meanwhile the LFP announced that it had made a formal complaint to the prosecution authorities against persons unknown “in order to shed all possible light on the circumstances in which confidential discussions and documents were divulged without authorisation”.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter