Hammadi Khlifi was there at the birth of the Arab Spring. On December 18th, 2010, he watched the first videos of clashes between the police and locals in his home town of Sidi Bouzid in central Tunisia. It was the day after Mohamed Bouazizi, a Sidi Bouzid street vendor, had set himself on fire, a protest against harassment that triggered the Tunisian Revolution and uprisings in other Arab states.

Khlifi took a bus from Sfax, Tunisia's second city, back to Sidi Bouzid and posted messages on Facebook warning of the violent incidents taking place there. And on December 27th his Facebook account was blocked and censured. His profile was returned to him on January 13th, 2011, the day before Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, the overthrown Tunisian dictator, left the country.

Now, six years later, his Facebook account has got him into even deeper trouble. On December 21st last year, Khlifi was arrested for posting of a picture of the current Tunisian president, Béji Caïd Essebsi, and his bodyguard with the comment: “Yes you can, we are all behind you.” This was a reference to the assassination of the Russian ambassador to Turkey by a Turkish policeman charged with his security.

Khlifi was arrested and taken with no explanation first to the police station, then to Bouchoucha detention centre in the capital, Tunis, where he was kept for 48 hours with no contact with the outside world. He also lost his job at the Sfax Truth and Dignity Commission.

Now Khlifi is waiting for a hearing before a judge. At 24 he faces a sentence of three years' imprisonment for incitement to murder under article 51 of legal decree 115 that covers the press in Tunisia. “The message was black humour that was wrongly interpreted. Under Ben Ali my profile was blocked but no one arrested me, given the chaos there was then. Six years later, I post a message and the next day I am taken to the police station. It's unheard of,” he said.

News of his arrest spread fast on Facebook. He says he was released ahead of his trial because of pressure from activists and people on social media. Facebook has become one of the country's main forms of communication, perhaps even of information, with six million Tunisians online, according to a recent report from Medianet Labs, a Tunisian web agency. From pictures of a snow-bound northern Tunisia to calls to help people in need, Facebook has become a media outlet, contrasting with certain official sources of information, which are tightly controlled.

In another example of repression linked to Facebook posts, last year two unionised police officers were arrestedbecause they posted comments on failures in the investigation into the 2015 terrorist attack on the Bardo Museum on their Facebook pages.

There have also been arrests related to terrorism offences in which the authorities have specifically cited the use of a Facebook account by the alleged perpetrators. In a press release published on December 23rd, the Tunisian Interior Ministry announced that a member of a Takfiri group had been arrested and that photos and videos glorifying Islamic State, or Daesh, had been found on his Facebook page. Last year the ministry published around 15 such press releases.

However, the authorities have made no distinction between people such as Khlifi and those involved in alleged terrorist activity. The trivialisation of Facebook has meant that potential terrorists are put on the same level as activists employing political caricature or defending human rights, or conservatives. And although Facebook was at the time a powerful tool for sharing information during the revolution, its use has since changed to reflect the divisions within Tunisian society. For some it is an example of freedom of expression, for whistle-blowers it serves as a means to leverage pressure, for others it is an outlet for ranting.

Each week local news, racist crimes or injustice in civil society are reported on its pages even before they are carried by the media. Amna Guellali, director of Human Rights Watch in Tunis, took to Facebook on January 16th to protest that representatives of civil society were refused an audience in Parliament for discussion on a draft bill on drugs. Three days later, associations were finally granted the audience they sought. “It made sense to put it on Facebook first,” she said. “The impact is bigger from the outset and it is a sounding board that allows information to propagate more quickly.”

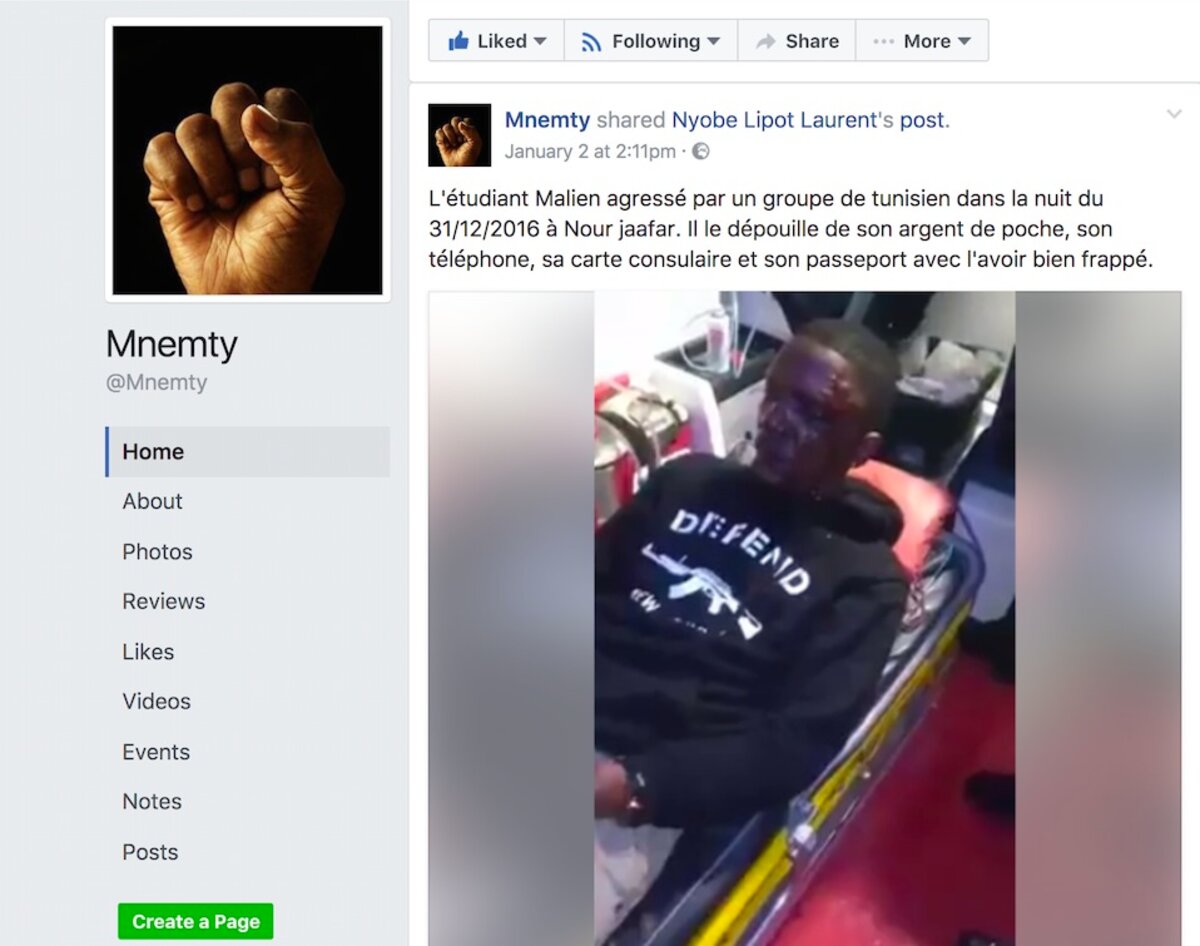

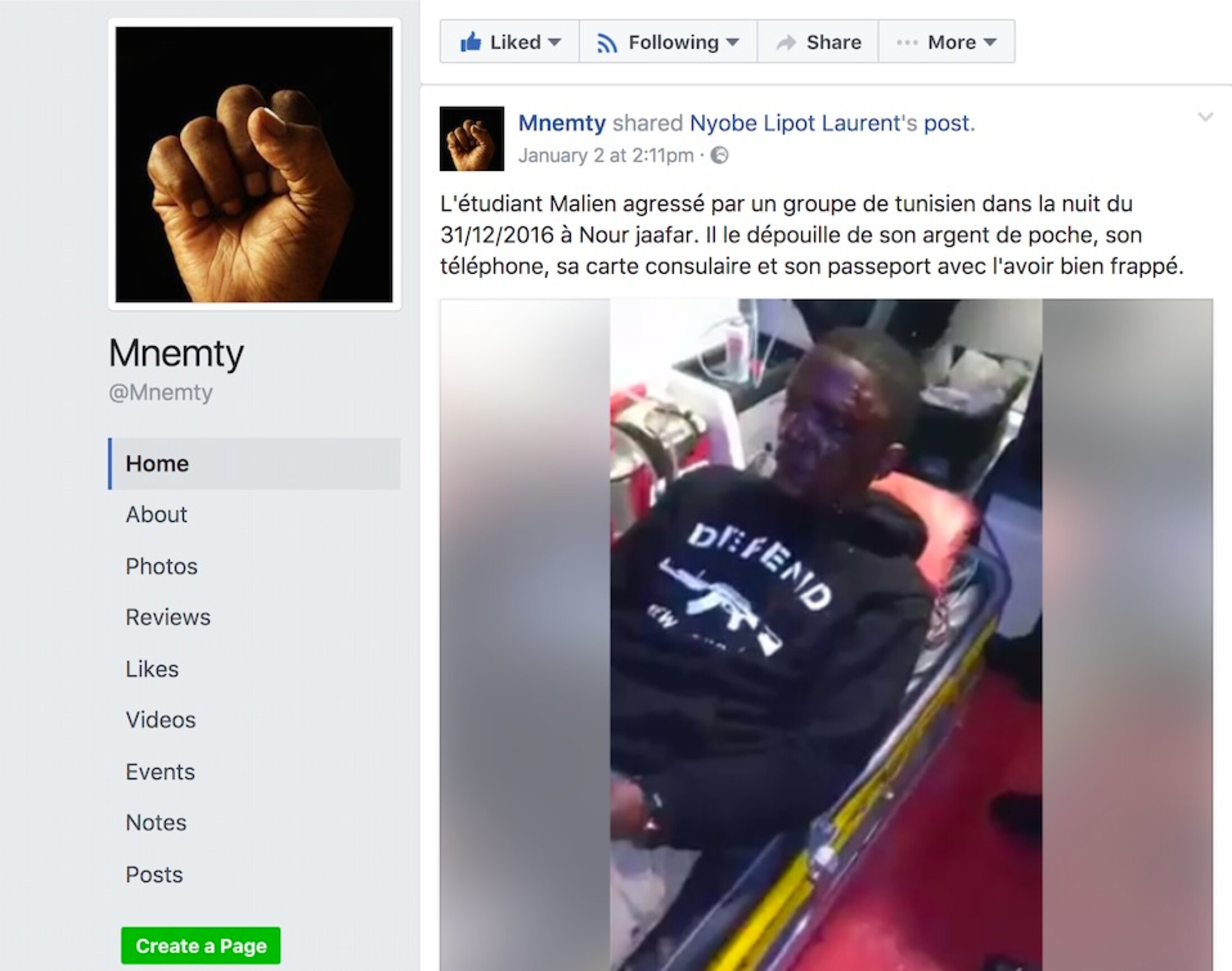

Saadia Mosbah, president of Mnemty, an anti-racist association, sees Facebook as a vehicle to effect gradual changes in attitudes. In late December it was the association's Facebook page that reported a racist attack on three Congolese citizensin Tunis city centre. “Facebook allowed us to group attacks together and denounce them and the various problems related to racial discrimination in Tunisia,” she said. “Thanks to this social media, daily insults like the term 'oussif ', which means slave, are tending to disappear from public arenas such as television, public offices and other local institutions.”

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Facebook has also become a useful tool for organisations defending lesbian, gay, bisexual and transsexual (LGBT) rightsto sound the alert over arrests of homosexuals or the anal tests that they are sometimes made to undergo. But even in these cases, using social media is a double-edged sword. People behind such Facebook pages often receive threats, and activists who post their opinions openly are not safe either.

'We were used to attacks from the government in power, not from Tunisian society'

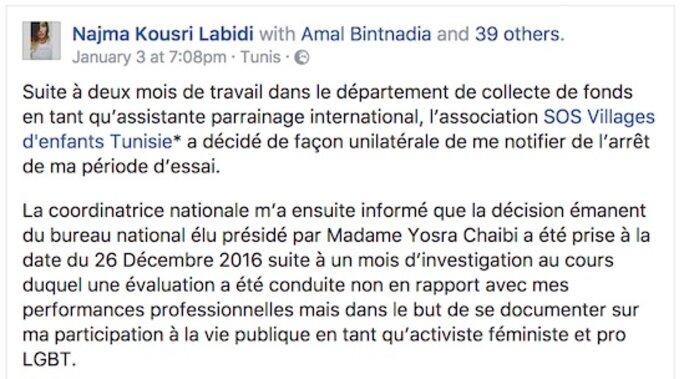

“As a militant for LGBT and women's rights I post a lot on Facebook,” says Najma Kousri Labidi, 25, a member of the Tunisian Association of Democratic Women. “That is how I receive testimonies and am also able to make contact with others.” But because of her open activism, she was fired from her job at a Tunisian NGO in early January.

Her post denouncing an unfair dismissal was widely shared on Facebook. “It started as soon as I took part in a campaign against sexual harassment last October. Some of my work colleagues consulted my profile and I got negative comments on some of my posts – which is very contradictory for the NGO I work for, which is supposed to defend human rights,” she said.

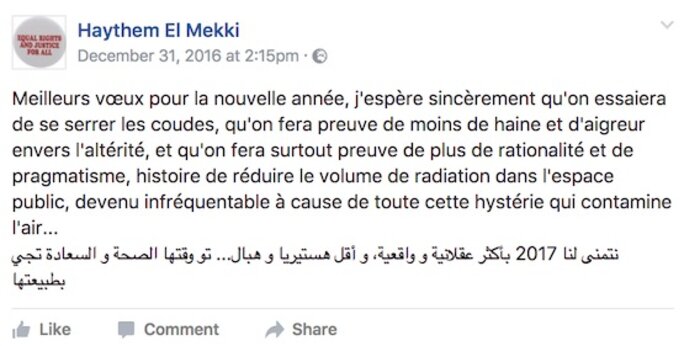

For many Tunisians, Facebook is no longer only a place of free expression for civil society. From 2012 to 2014 it became a ranting space where that freedom of expression was confused with propagating hatred and apology for terrorism, particularly as elections drew near. Haythem el-Mekki, a blogger before the revolution who is now a commentator for Mosaïque FM radio, calls this a “Facebookracy”, a perversion of democracy in which “everyone speaks without rules or moderation”.

He has 100,000 followers and is exposed to hate comments because of his free thinking, especially when he comments on political parties. But the threats are not the true danger, he says. He is more worried about misinformation and the way different types of information are given the same importance on Facebook. “We've had mob movements based on misinformation that circulated on Facebook, like the case of art works exhibited at the Al Abdellia Palace where people said the place was threatened by Salafists, or the case of a kid who set up a network for pornographic casting. That went a long way because the media commented on it, the government too, until people realised that all of it was just rumour,” he says.

As well as rumours, hate speech proliferates and there are often backward comments in social debates on Facebook. Scandals such as the case of a judge in El Kef forcing a 13-year-old girl to marry her rapist generate both indignation and approval on the internet. “It's appalling because we were used to attacks from the government in power not from Tunisian society, which is becoming more and more intolerant specifically on Facebook, with the screen of their smartphone or computer boosting people's feeling of impunity,” says Dhouha Ben Youssef, an activist for rights and liberty on the internet.

Facebook has become commonplace and ingrained in people's habits over the past two years in Tunisia, and intolerance and the constant circulation of 'buzz' news undermines the power of street mobilisation, she adds. “Although Facebook helped to mobilise people on the streets during the revolution and also during the two years that followed, nowadays demonstrating means commenting or sharing posts or being a troll.”

The rush to Facebook also has damaging effects on civil society, notes Kousri Labidi. “At the end of the day we're in a dialogue of the deaf in which everyone shouts what they can but the authorities do not hear. We should think about the weakening of civil society today and our inability to mobilise on the streets to demand our rights,” she says.

Facebook was behind a demonstration on January 8th calling for a rejection of the return of Tunisian jihadis from Syria. But it is hard to find demonstrations to defend human rights. And the overwhelming predominance afforded to the latest 'buzz' news tends to overshadow social movements in the country's interior. Ghassen Ben Khelifa, an activist against Ben Ali, says this benefits the government. “I think it is very convenient for the ruling government that Tunisians are more active on the web than on Avenue Habib-Bourguiba,” he says, referring to the main avenue in Tunis.

“We should not take Facebook for something it is not,” he adds. “Certainly it has always been a way of getting round official information and having other sources, but its role was vastly overestimated during the revolution, as it is today.”

Yet, there were real, as opposed to virtual, signs of progress around celebrations on January 14th of the sixth anniversary of the Tunisian revolution, despite the ubiquitous crisp and flag-sellers. That evening, the hearings of the Tunisian Truth and Dignity Commission, the transitional justice authority, were held and broadcast live on television for the third time.

As a result, statements from Amira Yahyaoui, a former president of NGO Al Bawsala, were picked up on Facebook. She was one of the people behind “Journée sans Ammar”, a protest in which Tunisians wearing white t-shirts demonstrated in 2010 against censorship of the internet.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Sue Landau