It began with an article published by Mediapart. Now it has become known in France as 'l'affaire Karachi' and dubbed 'Karachigate' by the international press. It is potentially one of the biggest French political scandals of the past two decades, engulfing President Nicolas Sarkozy along with a former president and two ex-prime ministers. It's a complex and fast-moving story involving multi-billion-euro arms deals, political funding, shell companies, shadowy intermediaries - and the murders of 11 French naval engineers. Here, Michael Streeter presents a clear 'questions and answers' guide to the affair, followed by a chronology of the main events.

----------------------------

Question: Why is it called the Karachi affair?

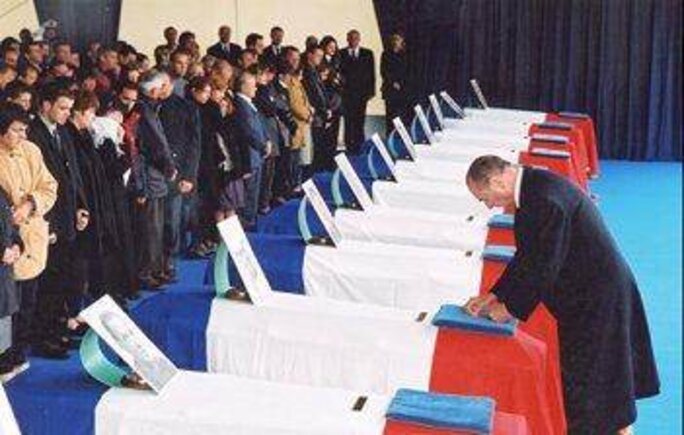

Because it centres around the murders, on May 8th 2002, in the Pakistani port city of Karachi, of 11 French naval engineers who were killed when a suicide bomber drove a car packed with explosives into the side of their minibus. Three Pakistani nationals, including the bomber, also died in the attack.

The engineers, employees of the French naval construction company DCN, were in Karachi to help build one of three Agosta 90B submarines sold by France to Pakistan in a deal concluded eight years earlier.

Their unsolved murders are the object of an ongoing official investigation in France, led by an independent magistrate. Both the Pakistan and French governments initially blamed al-Qaeda. However, that theory has now been cast aside by the French investigation, which is currently focussed on a very different lead that is causing significant embarrassment among France's political establishment.

Q: So what makes it become 'an affair'?

In short: because the investigation into the engineers' murders has uncovered strong evidence that the sale of the submarines involved money-laundering to fund a French political campaign in which Nicolas Sarkozy, well before he became president, was a key figure. While he has denied any involvement in the alleged scam, the incidents of official obstructions in providing information to the magistrate investigating the engineer's deaths have served to increase suspicions of a cover-up. Evidence from the investigation also suggests, but does not prove, that the murders of the engineers was indirectly the result of a high-level political spat in France which led to the source of the illegal party funds - bribes paid in Pakistan - being cut-off.

In detail: The magistrate investigating the engineers' murders is currently focussing his investigation on the theory that this attack was ordered in reprisal for a decision by French president Jacques Chirac's government (1995-2002) to cancel significant 'commissions' - in reality bribes - owed on the sale of the three submarines.

Although now outlawed by an international agreement, the paying of bribes in 1994 was legal and widespread to secure arms sale agreements. In this case they were paid to high-ranking local intermediaries, and were staggered over a period of time.

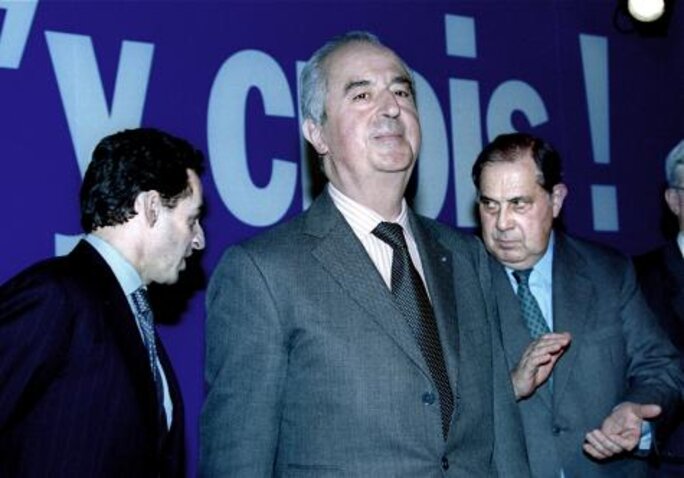

Chirac's order to cancel the outstanding payments on the Agosta submarine deal has been confirmed in testimony by his then-defence minister, Charles Millon, along with other witnesses.

Millon said Chirac was keen to purge immoral behaviour. The former defence minister said he had an "intimate conviction", following a review of the contract, that some of the vast sums of money set aside for bribes were actually re-routed back to France, via intermediaries and offshore structures. Unlike the payment of bribes to local intermediaries, which was then legal, it was illegal for bribe money to return to third parties in France.

The key allegation is that these so-called 'retro-commissions', bribes destined for Pakistan but ultimately cashed in France, were to help fund the failed 1995 presidential campaign of Edouard Balladur, a centre-right politician, rival of Chirac, who was prime minister when the submarine deal was signed. This would mean, in effect, that French public funds were secreted into the coffers of a political party via obscure financial structures.

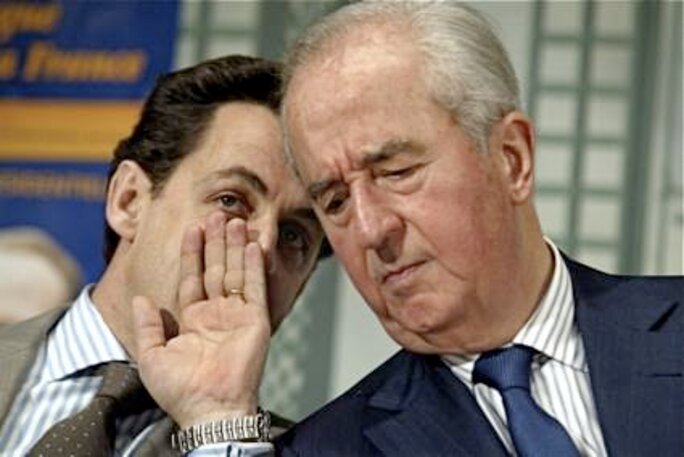

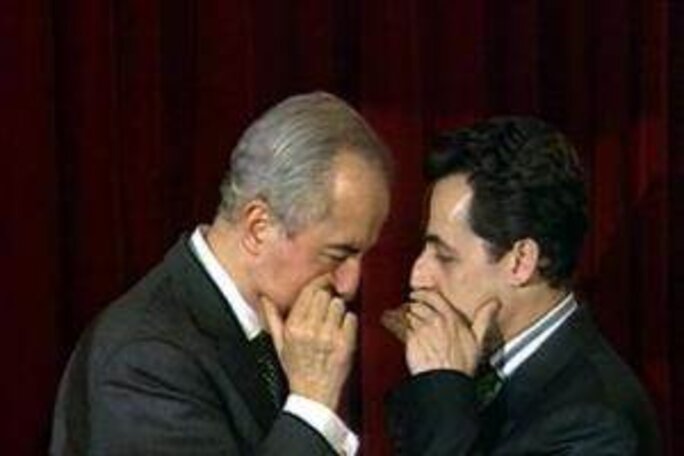

This allegation becomes even more important by the fact that the current French president, Nicolas Sarkozy, was Balladur's budget minister in 1994, and his election campaign spokesman in 1995 (see further below). It is argued, not least by the relatives of the dead engineers, that it would have been impossible for Sarkozy not to have been involved in organising the alleged illegal funding of the campaign via retro-commissions. Both men deny the allegation.

But what creates the 'affair' is the fact that until only recently (see further below), the Karachi blast was officially blamed on terrorism, while the stack of evidence that links it to the non-payment of bribes was shelved - until an examining magistrate uncovered part of it. The suggestion is that the real reasons for the attack on the engineers were known and kept secret within the corridors of power, suppressed from the families and public at large to avoid revealing a shameful political scam.

Q: What is the political backdrop?

The mid-1990s were the final years of socialist president François Mitterrand's long period in office (which consisted of two terms, from 1981-1995). The Centre-Right opposition led by Jacques Chirac, head of the Gaullist Rassemblement pour la République (RPR) party, won the parliamentary elections in 1993. President Mitterrand was thus forced to have a government and prime minister from the political right.

Chirac put forward his friend and ally Edouard Balladur as prime minister, allowing Chirac to concentrate on his campaign for the presidential election in 1995. However, Balladur soon acquired presidential ambitions of his own and broke his agreement not to run against Chirac. This caused a bitter political split between the chiraquiens - Dominique de Villepin and Alain Juppé among them - and balladuriens, who included Nicolas Sarkozy. Balladur's immediate problem was that he had no source of party funding to run his campaign; The RPR backed Chirac, not him. So he and his allies - who included defence minister François Léotard as well as budget minister and government spokesman Sarkozy - had to search for alternative funds.

Q: So where did Balladur's election war chest come from?

That is a key question. On April 26th,1995, after Balladur was eliminated in the first of the election's two rounds,10.25 million francs (about 1.5 million euros) were deposited into his campaign account in Paris in large denomination notes.

Balladur's team say the money came from collections at party rallies and from the sale of items such as T-shirts, a view dismissed by investigators working for France's highest constitutional authority, the Constitutional Council. Another theory was that the money came from

so-called 'special funds' that French prime ministers had access to at his time. These were significant chests of cash that were handed around ministries to be handed out as ministers and prime ministers so wished.

The third theory - central to the Karachi affair - is that the money came from the retro-commissions linked to the sale of three submarines to Pakistan.

Q: What is the difference between 'commissions' and 'retro-commissions'?

During the 1990s, when the submarine sale was concluded, it was still legal for French arms firms to pay 'commissions' - in reality bribes - to foreign dignitaries and decision-makers to persuade their country to buy defence equipment from France rather than another country. They could even be offset against tax. This was widespread, not limited to France. An OECD agreement among member states in 2000 finally outlawed the practice.

However, in 1994, it was already illegal for any of those commissions (i.e. paid to bribe local officials) to be channelled back into France. These are what are known as retro-commissions.

Q: Where are the Balladur retro-commissions said to have come from?

In 1992, before Balladur became prime minister, France was negotiating to sell Pakistan three Agosta-class submarines. By the summer of 1994, the deal was all but signed for a total value of 826 million euros (the value negotiated then in French francs). However, at the last minute, Balladur's government insisted that two

extra intermediaries be paid with commissions - bribes - totalling 33 million euros, even though other commissions had already been authorized under the deal. The allegation is that these monies were channelled through 'shell' companies, at least one of which is said to have been set up under the direct supervision of then budget minister Nicolas Sarkozy. And that they were then used to fund Balladur's election campaign.

Q: Who were these new intermediaries?

Lebanese businessmen Ziad Takieddine and Abdulrahman El-Assir. Takieddine describes Sarkozy as a "friend".

Q: When did stories of these illegal retro-commissions first emerge?

In political circles, almost immediately. Chirac's camp knew that his rival Balladur had no party political funding and there were rumours that the latter's campaign money came via arms deal commissions. In 1995, the newly-elected President Chirac ordered the examination of arms deal commission payments authorized when Balladur was prime minister. Chirac ordered that the payments be immediately halted in those where retro-commissions were found or believed to be involved.

Chirac's camp has presented this as an attempt to clean up public life. However, Chirac's own track record suggests probity was far from the top of his agenda. What has been widely suggested in the media and by a number of politicians, but unproven, is that it was bid to cut off the funds of the man who betrayed him and who could otherwise continue to represent a political threat. However, the fact that the Constitutional Council approved Balladur's election campaign accounts in 1995 - against the advice of its own investigators - helped prevent the stories becoming public.

It was only in September 2008, when Mediapart broke news of the existence of an internal DCN report linking the Karachi bomb attack to the cancellation of arms deal commissions, that the allegations began to emerge.

Q: What is the evidence for the retro-commissions?

There is the opinion of the Constitutional Council's own investigators about the dubious provenance of the 10.25 million francs that Balladur's campaign received in cash. If the money did not come from campaign rallies, where did it come from? Another is the evidence of Charles Millon, defence minister under Chirac in 1995 who Chirac put in charge of conducting internal inquiries into the existence of the retro-commissions. In his evidence in November 2010 to the judge investigating these illegal commissions he confirmed his "intimate conviction" of their existence in the Karachi deal. And in January 2010 Luxembourg police said that some of the funds that had passed through a shell company in the Duchy in 1995 "came back into France to finance French political campaigns".

Q: What are the ongoing investigations into the affair?

The main investigation into the Karachi bombing murders is led by French judge Marc Trévidic. His is a murder investigation, for under French law the deaths of French nationals abroad can be investigated - and those charged eventually tried - in France. The relatives of the engineers are civil parties to the case. His line of inquiry is that the bomb attack was a reprisal for the scrapping by Jacques Chirac's government of commissions linked to the Agosta submarine sale.

He has ruled out, for lack of evidence, the previously officially-supported theory that it was carried out by Al-Qaeda, even though they claimed responsibility for it. Two men sentenced to death in Pakistan for the atrocity have since been acquitted.

Importantly, and fuelling suspicions of a cover-up, Trévidic has been refused access to official documents on the grounds that they are classified as secret for national defence interests. He has also been denied access to transcriptions of the hearings of a parliamentary enquiry into the Karachi bombing in a move organised by the chairman of the assembly's defence commission, Guy Teissier, an MP from Sarkozy's ruling UMP party.

A second inquiry is being led by French judge Renaud Van Ruymbeke. He is investigating the financial background, and specifically whether retro-commissions from the Karachi submarine deal served to fund a political cause. His investigation was launched in spite of opposition from the prosecution authorities in Paris. The prosecution authorities ultimately answer to political masters. As part of the judiciary the investigative judges - also called examining magistrates - are independent. The prosecutor's office has launched an appeal to have Van Ruymbeke's case quashed on grounds of legal technicalities, and his questioning of witnesses appears to be a race against time before that appeal is heard in the coming weeks.

Q: What is Sarkozy's role in all this?

His name has come up on a number of occasions. He was budget minister and government spokesman under the government of Edouard Balladur (1993-1995). Sarkozy was then spokesman for Balladur's election campaign in 1995, the campaign suspected of using the illegal retro-commissions.

According to a January 2010 report by Luxembourg police, the creation of a Luxembourg company called Heine in late 1994 was supervised and approved "directly" by Sarkozy, who was then budget minister. This 'shell' company is said to have been used to channel commissions from the Agosta submarine deal. Between 2004 and 2006 the former boss of this company, Jean-Marie Boivin, tried to blackmail the then French government, demanding eight million euros in return for silence over what he knew about commission payments.

One of the letters was sent to Sarkozy. Boivin also went to see Sarkozy's former law firm partner. Boivin claims that on October 26th, 2006, he received a visit from two former intelligence agency officials, and was physically threatened. Boivin says they were sent by Nicolas Sarkozy, then the interior minister. This was just months before Sarkozy stood in and won the 2007 presidential election.

As president, Sarkozy has promised to help the Karachi victims' families find justice. But they complain bitterly of the obstacles preventing the investigation from advancing properly, notably the official refusals to hand over information to the judge. Sarkozy has dismissed the allegations about his involvement as "preposterous" and a "fairytale".

Q: What role have the Karachi victims' families played in the affair?

Represented by their dogged lawyer Olivier Morice, the families of the French victims have helped to maintain the momentum of the investigation. In particular, Morice has worked closely with Judge Trévidic. It was Morice's efforts that forced the launching of the separate, parallel investigation led by Judge Renaud Van Ruymbeke, which is now examining the question of retro-commissions. The families are also planning to sue former president Jacques Chirac and his then chief of staff Dominique de Villepin for manslaughter on the grounds that it was their cancellation of the commissions that caused the revenge attack in Karachi. Importantly, there is evidence suggesting they had been warned

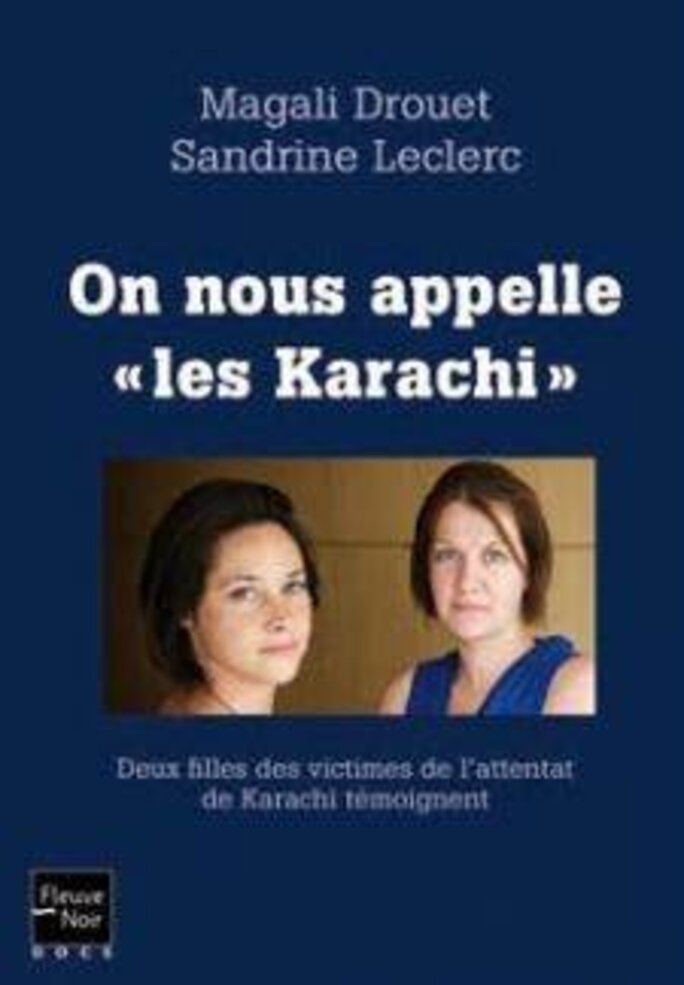

of the dangers. Villepin has already given evidence in both judicial investigations into the affair. The families are also pushing for President Sarkozy to give evidence as a witness. In November, Magali Drouet and Sandrine Leclerc, daughters of engineers murdered in the blast and who have become the spokeswomen of the relatives' campaign for justice, published an angry account of their ongoing struggle to discover the truth (On nous appelle 'les Karachi' - They call us 'the Karachis' -published in French by Fleuve Noir).

Q: What are the likely ramifications of the affair?

Potentially huge. The Karachi scandal could haunt Nicolas Sarkozy for the rest of his presidency. This in turn could have a knock-on effect on his likelihood of getting re-elected as president in 2012. If Sarkozy were found to be implicated in illegal party funding then he could not be prosecuted while in office, because of presidential immunity. But the prosecution of anyone close to Sarkozy over the affair would be politically damaging, not to say politically fatal for him.

The Karachi affair has also re-opened political wounds on the right between the balladuriens and the chiraquiens. However, whether the engineers' families will ever learn the whole truth about the retro-commissions and exactly why they were murdered in May 2002 remains open to doubt.

-------------------------

Click here for Mediapart's video presentation of the story, with English sub-titles. NEXT PAGE NOW: The chronology.

How the scandal grew: a chronology of the Karachi affair

1992

September - Commissions totalling 52 million euros agreed by French defence contractor DCN in relation to proposed sale of three Agosta-class submarines to Pakistan.

1993

March 29 - Edouard Balladur becomes prime minister under President Mitterrand.

March 30 - Nicolas Sarkozy becomes budget minister and government spokesman.

1994

Summer - Government of Edouard Balladur orders two new intermediaries and 33 million euros in new commissions to be added to Agosta deal even though sales contract is just awaiting signature.

September 21 - Agosta contract signed.

November 18 - Creation by DCN of Luxembourg-based company Heine.

1995

January 28 - Balladur announces running for presidency against centre-right colleague and friend Jacques Chirac.

April 23 - Balladur eliminated in first round of presidential election.

April 26 - 10.25 million French francs (about 1.5 million euros) deposited in large denomination notes in Balladur's campaign bank account in Paris.

May 7 - Jacques Chirac elected president of France. Chirac quickly orders new defence minister Charles Millon to identify those arms contracts containing retro-commissions signed under premiership of his rival Balladur.

October 3 - Investigators working for Constitutional Council recommend rejecting Balaldur's election accounts.

October 11 - The Council approves the accounts.

1996

July - The Agosta contract intermediaries used by Balladur's government are informed they will not get the balance of the commissions due to them.

1997

September - French armed Forces controller-general Jean-Louis Porchier starts inquiry into Agosta contract.

1998

May - Porchier delivers report. Based on what he has found out, he is asked to start another inquiry in tandem with the financial investigation authorities, the Inspection générale des finances (IGF).

1999

March - Porchier delivers final report to defence ministry. It remains classified.

2000

September 28 - OECD-negotiated agreement outlawing corrupt payments - bribes - to foreign officials adopted into French law.

2001

September 21 - internal DCN memo confirms that remaining commission due to Agosta intermediary has not been paid.

2002

May 5 - Jacques Chirac re-elected president of France.

May 8 - car bomb aimed at bus carrying DCN staff working on Agosta contract in Karachi kills 14, 11 French citizens and three Pakistanis.

May 27 - judicial inquiry into murders begins. Anti-terrorist judge Jean-Louis Bruguière works on theory that blast was work of Al-Qaeda.

September - former counter-espionage official Claude Thévenet concludes inquiry into the bombing. His report, known as Nautilus, concludes that blast was linked to Agosta contract commissions.

December 4 - Two men, Asif Zaheer and Mohammad Rizwan, arrested by police in Pakistan on suspicion of being involved in the murders.

2003

June 30 - Asif Zaheer, Mohammad Rizwan and a third man Muhammad Sohai - said to be on the run - sentenced to death in Pakistan for carrying out the attack.

2006

- In series of private letters to senior people in French state, Jean-Marie Boivin, former boss of Luxembourg-based company Heine, threatens revelations about commission payments unless he is paid eight million euros.

26 October - Boivin receives visit from two former security agency officials over his threats and he claims they were sent by then-interior minister Nicolas Sarkozy and that he was threatened physically.

2007

January - Jean-Louis Bruguière resigns from his job as magistrate to begin a political career with Nicolas sarkozy's UMP party. He is replaced by judge Marc Trévidic who starts the inquiry from scratch.

May 6 - Nicolas Sarkozy elected president of France.

2008

April 4 - President Sarkozy meets families of Karachi victims and promises he will do all he can to help the inquiry.

September 13 - Mediapart reveals existence of Nautilus report. Judge Trévidic requests that the authorities send him a copy.

2009

January 24 - Boivin signs an agreement with the DCN and French state in relation to Heine and its activities.

May 5 - Asif Zaheer and Mohammad Rizwan are acquitted by the High Court in Pakistan which says there is no proof they were behind the attack.

June 18 - Judge Trévidic tells Karachi victims' families that he is no longer looking at the theory that Al-Qaeda were behind the attack. From now on the investigation will focus on the lead that it was linked to the cancellation of commissions by the Chirac government.

June 19 - President Sarkozy describes theory that attack was linked to commissions and retro-commissions that financed Balladur's campaign as a "fairytale".

2010

19 January - report by Luxembourg police says that as budget minister Nicolas Sarkozy was "directly" involved in setting up the company Heine that was used to channel commission payments.

May - Mediapart journalists Fabrice Lhomme and Fabrice Arfi publish their book "Le Contrat" on the Karachi affair.

June 28 - Boivin is interviewed under caution by judges Françoise Desset and Jean-Christophe Hullin who are investigating separate allegations of corruption at the DCN.

June - Victims' families make formal complaint about the impeding of justice, false testimony and corruption in relation to the investigation into the Karachi affair.

September 14 - Under pressure from the families' complaint, Paris prosecution authorities hand new investigation into impeding justice and false testimony - but not corruption - to experienced judge Renaud Van Ruymbeke. Working in parallel with Judge Trévidic, however, within weeks he announces he is opening an investigation into the issue of the retro-commissions, i.e. alleged corruption.

October 7th - The Paris public prosecutor's office launches an appeal (in the Paris Appeals Court) to have Van Ruymbeke's investigation annulled. The Court's decision on this is pending.

November 9 - Former DCN finance director Gérard-Philippe Menayas confirms existence of blackmail by Boivin against the French state in relation to Heine and commission payments.

November 10 - Speaker of the National Assembly Bernard Accoyer refuses to hand over to Judge Trédivic the witness statements of 60 people who gave evidence to a parliamentary inquiry into the affair.

November 19 - Prime Minister François Fillon refuses permission for Judge Van Ruymbeke to search the offices of the French intelligence agency the DGSE which had been involved in investigating the commissions paid in the Karachi deal.

November 22 - Giving evidence to Van Ruymbeke, former defence minister Charles Millon confirms that after his investigations he concluded retro-commissions were paid in the Agosta arms deal. He suggests they were also paid in a separate arms deal also concluded under Balladur's premiership - the sale to Saudi Arabia of three La Fayette-class frigates. This deal, worth three billion euros (at the time negotiated in French francs) was officially called Sawari II.

November 30 - Judge Van Ruymbeke asks for official sanction to extend the brief of his corruption investigation to the Sawari II contract.