The year 1974 marked a turning point in France’s nuclear weapons tests. After eight years of atmospheric nuclear testing, the military decided to begin a series of underground tests, regarded as cleaner and, above all, less visible. But before that, France’s “Pacific experimentations centre”, the CEP, had established a programme for the final series of atmospheric tests which was described in an internal document as being “extremely tight”.

The document was a 110-page report, dated November 26th 1974, on the subject of the last series of atmospheric blasts that had by then recently come to an end. “The difficult balance between security imperatives and the demands of the calendar” had been “brought to the limit of breaking point”, it noted.

It was in that political and scientific context that, on July 17th 1974, France proceeded with its 41st atmospheric nuclear test, triggered over the atoll of Mururoa. The codename for the bomb was “Centaure” (Centaurus).

Using available meteorological data from the date of the explosion, along with scientific measurements of the size of the post-blast radioactive cloud and also previously unpublished information from French military archives, we have modelized the hour-by-hour trajectory of the fallout.

This study shows, for the first time, the extent of the radioactive fallout that landed on the island of Tahiti and the 80,000 inhabitants of its principal city, Papeete, the capital of French Polynesia.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Just 24 hours before the bomb was triggered, the weather forecast by the French test programme’s meteorologists calculated that the radioactive cloud would travel north, reaching the Tureia and Hao atolls in the space of 20 hours. Further weather checks were made 12 hours before the blast was due, and which confirmed that the cloud would indeed take the northerly direction towards Tureia and Hao.

But for the French military command, there was no reason to justify interrupting the operation. A preparatory report concluded that the risk of contamination for the population would be “sufficiently weak” to allow for the atmospheric test to go ahead.

At the time, Tureia was inhabited by about 60 civilians and several hundred soldiers. As for the Hao atoll, it was mostly populated by French air force personnel housed at a military base. Despite the numbers of people who were directly in line with the expected path of the cloud, Vice Admiral Christian Claverie, the then military commander of France’s Pacific nuclear test centre, gave his authorisation for the bomb to be triggered.

As expected, the explosion of Centaure formed an immense mushroom cloud within minutes. But there was a problem: it did not reach the height forecast by the scientists. Instead of rising to 9,000 metres as they believed it would, it reached a ceiling point at 5,200 metres, and at that altitude the prevailing winds did not blow it northwards, but instead towards the west. Lying almost directly on its path was Tahiti, the largest and most populated island in French Polynesia.

One hour after the explosion, the radioactive cloud began reaching Tematangi atoll, which was the location of the nearest meteorological station to Mururoa atoll from above which the bomb was triggered. The cloud then moved on to the inhabited atoll of Nukutepipi, nicknamed “billionaire’s island”, and across to the atolls of Anuanurunga and Anuanuraro. The fallout reached Tahiti at around 2am on July 19th 1974.

Between the triggering of the bomb and the arrival of the radioactive cloud over Tahiti, more than 42 hours had passed and yet the island’s population was not informed of the approaching nuclear fallout. Despite the gravity of the situation and the high risk of contamination, the local inhabitants were not asked to take shelter nor to refrain from consuming foodstuffs and water which the authorities knew would be contaminated.

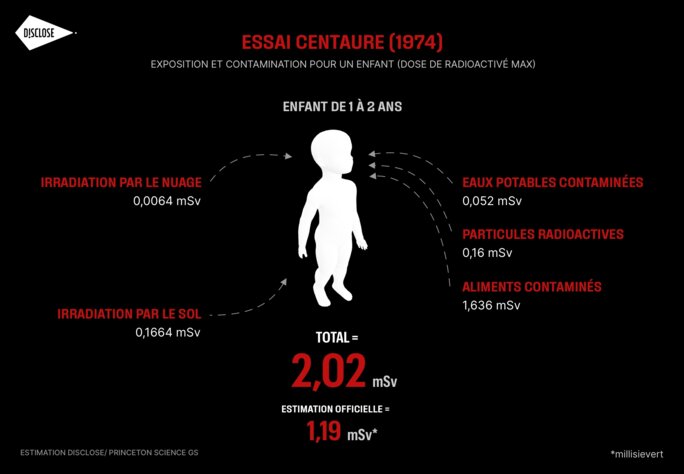

By studying data from declassified French military documents, Disclose re-evaluated the radioactive doses to which the population was exposed from the explosion of Centaure. The resulting estimations are that the inhabitants of Tahiti and the surrounding islands of the Windward group were subjected to doses of ionizing radiation higher than 1 millisievert (mSv).

For an individual to be recognised as a victim, according to the criteria of France’s official Committee for the Indemnification of Victims of Nuclear Tests, the CIVEN, they must prove that they received a dose of at least 1 mSv from the fallout, and developed any of 23 illnesses officially recognised as potentially radio-induced. The population affected by the fallout on and around Tahiti in 1974 numbered around 110,000.

To reach our conclusion on the doses of ionizing radiation to which the population was exposed, Disclose used data collected by the French joint radiological safety service, the SMSR, at the time of the explosion. This is the same data cited in a 2006 report by the French atomic energy commission, the CEA, in its re-evaluation of the doses of radiation to which local inhabitants were exposed. But comparing our calculations with those of the CEA, we found that the latter underestimated the level of exposure by around 40%.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

That underestimation is the result of three miscalculations, as is revealed by a close study of the methods used by the CEA 15 years ago.

Firstly, in order to calculate the effective dose, which is radioactivity a person is exposed to over all of their body, the CEA experts used as their reference only the radioactive deposits recorded on the ground during the first day of the contamination. Yet in fact, new radioactive deposits were recorded to have fallen over the first three days following the cloud’s arrival. But instead of the 3,400,000 becquerels per square metre that were then recorded, the CEA cited a figure that was 36% less.

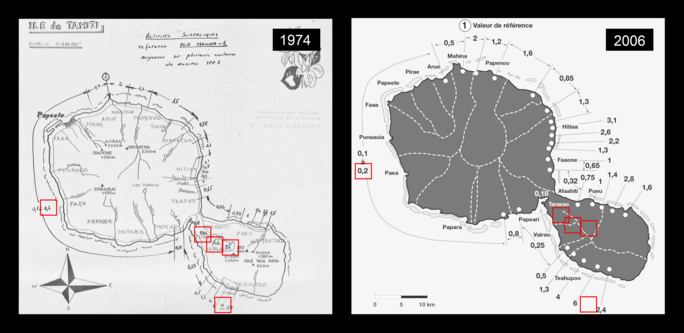

Furthermore, the CEA scientists used as their reference only those measures recorded at their main base on Tahiti, at Mahina, close to the French Polynesian capital Papeete, without taking into account measurements elsewhere on the island, and which were higher. This is shown on a map drawn up at the time, and reproduced below.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

The CEA featured the map in its report published in 2006, but it omitted to include some key recorded measurements, like those made at Teahupoo, in south-west Tahiti, which recorded the highest radioactive contamination, and those taken on the Plateau of Taravao, another of the most contaminated zones, situated in the south-east of the island. But the most flagrant redaction of the map concerned the zone of Papeete, where the recordings of radioactivity on the original map were decreased in value, without explanation.

After Disclose corrected the data modifications, this showed that the exposure to radioactivity of the inhabitants of Papeete was twice as much as presented in the official figures. In the case of Hitiaa, situated on the north-east of the island and which was exposed to a large amount of fallout, we calculate that the dose that infants aged under two would have received to their thyroids may have exceeded 50 mSv, as opposed to current official estimations of 49 mSv, and would today justify preventive treatment with iodine supplements. Meanwhile, an adult living in Teahupoo at the time would, we calculate, have received an effective dose of 9.40 mSv – twice as much as the estimates by the CEA.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Last September, Disclose met in Tahiti with one of the victims of the Centaure nuclear bomb blast. Aged 11 at the time, Valérie Voisin has few recollections about the summer of 1974, when her island was covered with radioactive fallout. She was then living in Papara, a few kilometres from Papeete. What the mother-of-three does remember clearly is the cyst that appeared on her left breast afterwards. Thirty years later it was removed, when she was diagnosed with cancer in 2008.

Valérie Voisin’s illness has had terrible and irremediable consequences; she has lost all her teeth and suffers from a degenerative spine condition, and a weak hip. “My doctor told me I have the skeleton of a lady of 90,” she said. Now she wants her five nieces to undergo medical tests, but they are refusing to do so. “They are frightened about what the doctors might find,” she explained.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- A French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse