A legal battle at the Paris Commercial Court replete with secret investors, fabulous profits and serious conflicts of interest has lifted the lid on the inner workings of French private equity funds.

Mediapart's Laurent Mauduit has gained exclusive access to the details of the case that pits Atria Capital Partners and Pragma Capital against Massena Capital Partners. Among the investors caught up in the dispute are the Californian state teachers' retirement system, CalSTRS, the largest US teachers' retirement fund, British fund Pantheon Ventures and French giant Axa.

-------------------------

Private equity funds are capital investment firms not listed on the stock market. They specialise in asset management for wealthy clients. Working far from the hurly-burly of the market, these firms and their clients prefer to stay in the wings, out of the public glare.

The long-simmering dispute between Atria Capital Partners and Pragma Capital against Massena Capital Partners is now due to erupt into a very public washing of dirty linen early this year in the Commercial Court of Paris (see full details of each party's arguments in the tab marked 'PROLONGER', top of page here).

Mediapart's investigation into the affair highlights the surprising financial mores of certain actors in venture capitalism, the sector of French capitalism where activities are the most concealed. The case is all the more high-profile in that one of the investors involved is sector heavyweight Axa Private Equity, with a portfolio of 25 billion dollars, along with major American, British and European funds.

It opens the door to the world of investment banking of a type that, over the past ten years, prospered in France and which dips in and out of the capital of Small- to Medium-sized businesses (SMBs). In circles where silence usually reigns and where dirty linen is laundered in private, this rowdy courtroom clash is all the more uncommon and worthy of interest.

The heart of the matter is that Massena considers that its interests were wronged and has taken the unheard of step of filing a suit against Atria. The legal procedure sheds a light on staggering practices - worthy of a three card Monte -which produce no added wealth or value but are, nonetheless, worth millions in capital gains. Practices that saw the rapid enrichment of the fund managers who paid slight attention to rules concerning conflict of interest, and who were subject to derisory tax rates.

When misdeeds occur, the French press largely focuses on those of the best-known CEOs, those from blue-chip CAC-40 companies as they cash in their barrels of stock options or their too generous golden parachutes. The media also focuses on the large investment funds that are invading the Paris stock market, dictating their terms, imposing their rules of corporate governance or of shareholder value. But beyond the known world of listed companies - known because the markets require a certain level of information - there exists a circle that is much less well-known: of firms that are not quoted and thus less transparent.

The case began in 2000 in the most routine manner. Atria Capital Partners launched a special type of fund that invests in unquoted companies, called Atria Private Equity Fund 1 (APEF1). Atria is one of many asset management funds which, based on the American model, is now well-established in Parisian financial circles. Its mission is to seek out innovative or highly-profitable SMBs in which to invest. Shareholder funds are invested for several years then traded, if possible with a hefty capital gain.

Atria is a small, independent management firm, founded by Dominique Oger (pictured left and whose website can be consulted here). Although not large, Atria represents a respectable portfolio. Its shareholders put 124 million euros into the pot for the APEF1 fund, of which the largest single contribution, a sum of 38 million euros, was supplied by Axa Private Equity. Axa Private Equity's CEO is Dominique Sénéquier, a leading European proponent of capital investment and a well-known figure in international financial circles.

The APEF1 fund followed the rules ordinarily regulating all funds of this kind. Each investor pledged a total amount of capital. Each time a new acquisition was made, shareholders paid a share of the pledged capital. But they had no voice in selecting acquisitions made by the fund or in its management. In this case, fund manager Atria had carte blanche to make the acquisitions it deemed promising and to trade them later. The only guarantees for investors were the regulations of the fund to which they subscribed.

As a general rule, an investment fund usually begins to sell off assets after five years. Most of the time, the fund's conditions are that it winds up after ten years. Then, if all goes well, the initial shareholders can hope to earn a substantial capital gain over the initial investment. Payment of fund managers is based on the capital gain and is also detailed in the fund regulations. In most cases, the managers share 20% of the gains obtained for their clients if the fund has made the predicted gains, which on average are around an annual growth of between 7% and 8%. In financial jargon, this 20% cut of the profits set aside for the fund managers is called the ‘carried interest'. This notion is at the crux of the case.

Managed by Dominique Oger and his staff, APEF1, Axa funds included, operated on this basis for several years. Acquisitions were made then traded a few years later when a sizable capital gain was to be made. The Atria website provides a comprehensive list of investments made by the firm in recent years and those of two other funds it manages (more here).

A comfortable gain of 48 million euros

Enlargement : Illustration 3

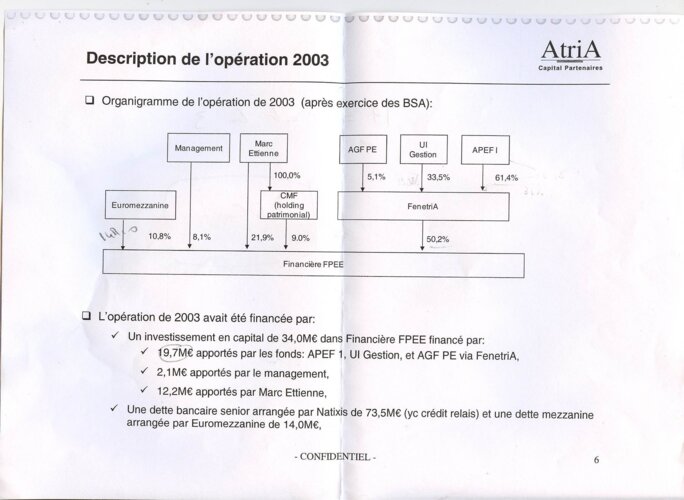

In 2003, APEF1 paid 12 million euros for a 30.8% share in FPEE, a high-performance SMB of 650 employees. The company has five production sites and is specialized in the production of window frames and industrial carpentry (see its website here). As shown by the diagram below (available in French only), this acquisition was made through an intermediary company, Fenetria. Fenetria is controlled by APEF1 in conjunction with AGF Private Equity and UI Gestion, a company tied to France's Crédit Agricole bank.

Click document to enlarge

Enlargement : Illustration 4

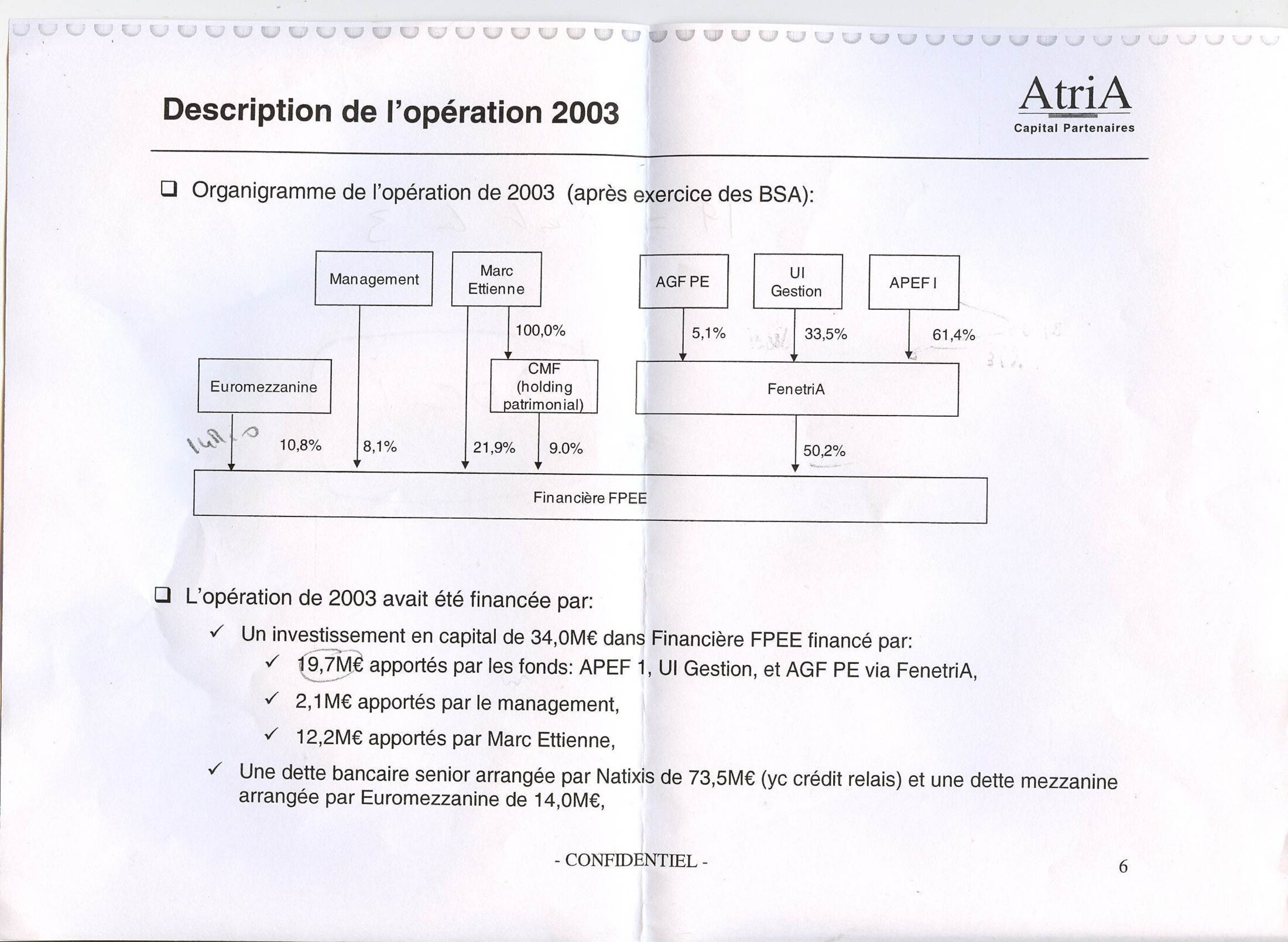

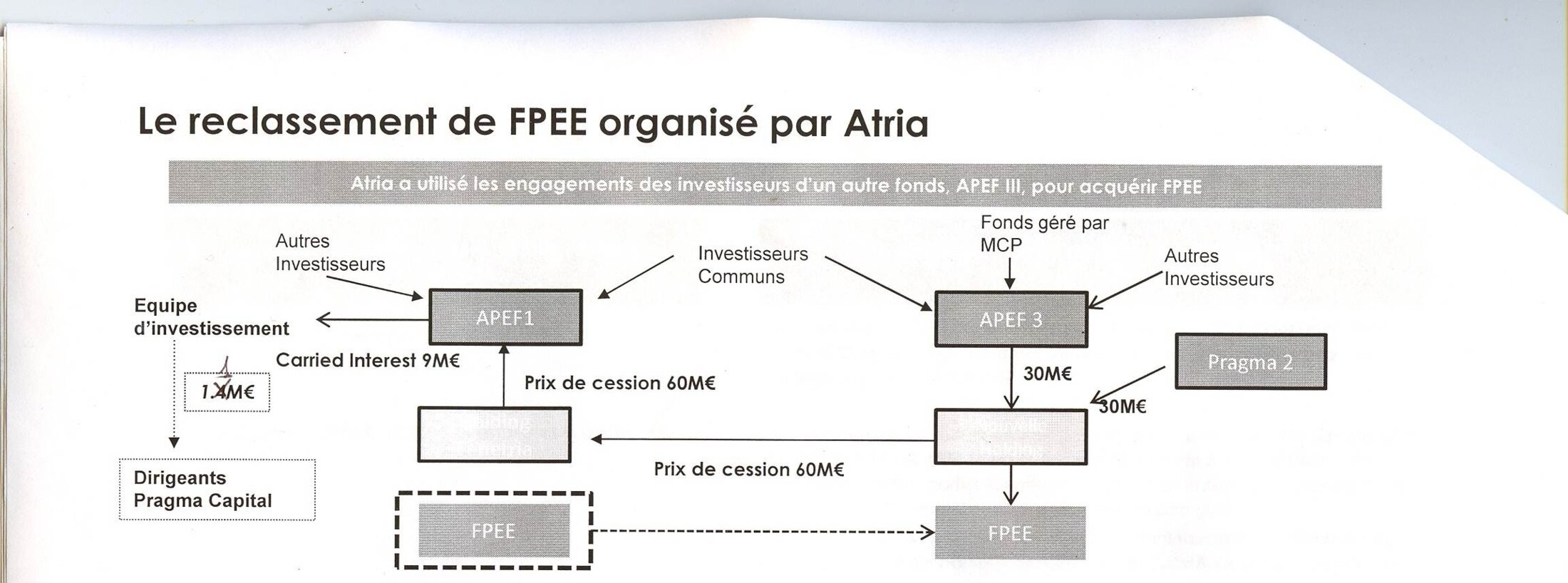

When the APEF1 fund was wound up at the end of its ten-year life span, it had sold off all of its acquisitions except for one. In 2009, just months before it was due to wind up completely, the fund still held the FPEE shares acquired in 2003. At this time an asset transfer was implemented, and that move lies at the heart of the story. Atria opted to transfer the fund's assets to another of its funds.

Atria manages three investment funds (presented here). These are APEF1, which raised 124 million euros in 2000 and invested in 14 companies; APEF2, which raised 196 million euros in 2004 and invested in 11 companies, and APEF3, which raised 300 million euros in 2006. Atria decided to asset transfer the APEF1 holding into the APEF3 fund. In other words, APEF3 bought 50% of APEF1 shares in FPEE. The other 50% stake was acquired by an outside fund, Pragma2, managed by Pragma Capital (its website is here).

The operation itself is legal. When a fund winds up, the fund manager, who has carte blanche in asset management, is allowed to transfer the assets of the old fund to another vehicle which he also manages. But this type of asset transfer transaction is strictly bound by the fund management regulations; by ethical rules especially those concerning conflict of interest; and it must be performed in a transparent manner.

Yet, this particular operation piqued the interest of one of the APEF3 investors, Massena Capital Partners, which naturally seeks to ensure its funds are being well managed.

Massena (its website is here) is an independent asset management firm that manages the wealth of several well-off families, mostly by investing in other management funds. It's a kind of fund of funds, or a ‘multi-family office' as it's called in these circles. Mediapart has learnt that Massena manages a number of ranking private fortunes from northern France. Like all financial institutions of this type, its reputation is performance-based but discretion is also highly valued - the golden rule is not to rock the boat. Massena's stake in APEF3 is a mere 10 million euros, a small share of the 300 million euros the firm manages. It's also a minority partner in the fund. It therefore has no particular interest in calling attention to the transaction.

However, the curious character of the operation caused Massena to become intrigued. Later it ignored calls for funds to which it had pledged to contribute, worried that its clients were wronged by the transaction. It attempted to find a solution, but this proved impossible and Massena was forced to bring the case to the attention of the courts.

The first question raised by Massena regards the cost of the transaction. Acquired for 12 million euros in 2003 by APEF1, the stake in FPEE was sold in 2009 for 60 million euros. APEF3 paid 30 million euros, a 50% stake and Pragma2 provided the other 30 million euros required. With a capital gain of four times the initial investment in six years - a comfortable 48 million euros earned-this was a satisfactory transaction for APEF1. The company hit the jackpot, through an investment in a large SMB.

But for Massena, the cost of the transaction was surprising. In 2009, the financial markets were reeling from two successive years of severe turbulence. The venture-capital sector had collapsed according to an overview of the French market (see below or download from here, available in French only).

To enlarge the document, click on Fullscreen.

The figures speak for themselves (see page 6 of the document). In France, because of the financial crisis, the number of leveraged buyouts (LBOs) shrank from 15 operations per 4.542 billion euros in 2008 to 2 operations per 247 million euros in 2009. In a market paralysed by the crisis, Massena management had doubts over the regularity of the fabulous capital gains realised by Atria by selling itself part of its own assets. Massena management claim that the APEF3 fund management regulations have been abused or violated. That claim was the opening salvo in the judicial battle. Calling on advisors such as the lawyer Jean-Pierre Versini-Campinchi and a well-known law professor specialising in stock market issues, Jean-Jacques Daigre, Massena requested and obtained the appointment of an expert to assess the market value of FPEE and is now bringing the case to the Commercial Court of Paris.

The cost of the transaction is the main issue of discord between Massena on the one hand, and Atria together with Pragma on the other. "The independent expert should have provided the market price," Massena's attorney, Jean-Pierre Versini-Campinchi, told Mediapart. "When the operation began [editor's note: late 2008/early 2009], the market was near-dead. He gave it an abstract economic value, not the market-value."

Dominique Oger, founder of Atria, countered: "Massena's criticisms are not justified," he protested. "The price is right, it's a brilliant operation, it is obviously perfectly legal. No detriment was caused. The truth is that Massena had first wanted to sell itself off at a good price. Without success. Massena then attempted an operation to denigrate us among the 70 other investors in the fund. Again without success."

"APEF1 is not being asset transferred to APEF3. If our APEF3 fund is participating in a capital restructure by managers along with new third-party investors, it's quite simply because we believe in the firm concerned. As for the price, let's also add that, during the capital restructure other top rank investors joined us, in the same conditions as those of APEF3, in the capital restructure of FPEE," Oger told Mediapart.

"Sincerely, I don't understand the dispute, because no detriment can possibly have been incurred," argued Pragma attorney Maurice Lantourn, also interviewed by Mediapart. "It is even the opposite that is true. All the investors have reason to be delighted, because this is an exceptional operation. The best way to judge if it was a good deal is to see if there is a virtual capital gain. And in fact there is a very high one," Lantourn concluded.

[Editor's note: The complete arguments and replies supplied to Mediapart by the different parties concerned in this affair can be found by clicking on the ‘Prolonger' tab at top of page.]

A carried interest of 11.464 million euros

This version of the case is not corroborated by the expert report submitted to the court and which Mediapart has been able to consult. Both Pragma and Atria contest the conclusions of the report and want it annulled. Commenting the cost of the transaction, the report said that it was "probable that Atria sensed that if the bank [editor's note: asked to handle the sale] had solicited the deal, it would no doubt have received some interest, but at a price strongly impacted by the prevailing crisis atmosphere."

But the differences go beyond the question of price alone. There are two other bones of contention. The operation is protected by three security mechanisms defined in the APEF3 regulations. Of the three security clauses, two must be imperatively met. The first is that the shareholder advisory committee must approve the transaction and secondly, either an independent expert must set the purchase price or an independent investor must join the business transaction to back the APEF3 fund.

These APEF3 regulations, requiring that two out of three criteria be met, is similar to the rules applied to all investment funds and follows the two codes of ethics set out by the French Association of Capital Investors (available here in French only and the ethical code of management firms (download available here in French only). On page 13 of the latter, the ethics code sets out the obligations that must be followed in this type of transfer operation.

Here again, the expert's report lifts the veil on some strange practices. It notably shows that Axa Private Equity invested heavily in APEF1 and is also the main investor in APEF3 with a 30 million euro stake of the 300 million-euro pot. The group is therefore present in both shareholder advisory committees - that of the vendor fund and that of the buyer fund.

In this very complex transfer operation, as seen in the diagram below (available in French only), Axa Private Equity is also an investor in the Pragma2 fund, backing APEF3 to buy the controversial assets from APEF1 to the tune of 60 million euros; 30 million paid by APEF3, and 30 million met by Pragma2. Issues of conflict of interest are clearly raised.

Click on the document to enlarge

Enlargement : Illustration 5

The expert's report comes down harshly on the risk capital giant: "Axa Private Equity does indeed find itself in a situation where there is a conflict of interest, and this involves a double, and even triple, interest." It adds: "Atria should either have abandoned its plan or restructured its advisory committee in such a way as to bring in investors who did not have a conflict of interest."

Axa Private Equity's legal counsel, William Bourdon, strongly contests this analysis of the situation: "He is totally wrong. The expert starts from an incorrect assumption concerning the role of the advisory committee, which is not in any case ever empowered to take a view on the price, but only to obtain assurances that the procedure, in particular that covering conflicts of interest, has been observed in conformity with Atria's internal rules. Therefore the expert's conclusion is in fact erroneous both in terms of the law and the facts. The expert could have avoided this error if he had taken the time to question all the protagonists, and notably the representatives of Axa Private Equity."

But there are even more surprising things to be found under the third criterion, which creates an obligation for APEF3 to find an ally to buy the asset from APEF1, in order to guarantee the fairness of the transaction price. The intention here is not hard to understand: if Atria could simply buy an asset internally, transferring it from one fund to another and pocketing a hefty capital gain on the way, there would be legitimate doubts as to the fairness of the transaction. However, if another independent investor came in and backed the purchase, this doubt disappeared. Why would a new investor agree to pay over the odds for the purchase?

So in a formal sense everything was done according to the rules, because, as we have seen, APEF3 linked up with Pragma on a 50-50 basis to buy the asset from APEF1. But there is a catch. In fact, Massena soon had doubts about the true independence of Pragma, whose two top managers are Gilles Gramat and Jean-Pierre Créange.

On this point the expert's report confirmed Massena's fears. First of all, Pragma is affiliated with UI Gestion, which took part in the purchase of the asset at the heart of this controversy with APEF1 in 2003.

But above all, according to information made available to Mediapart, Pragma's own managers had a financial interest in the capital gain made by APEF1. This means the supposedly independent joint buyers actually benefitted from the gain made by the seller.

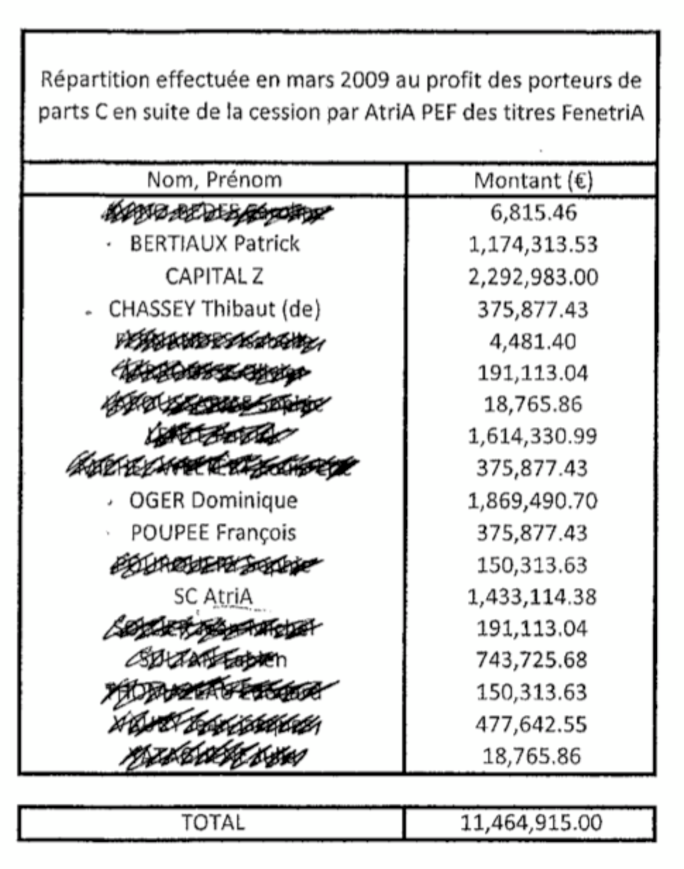

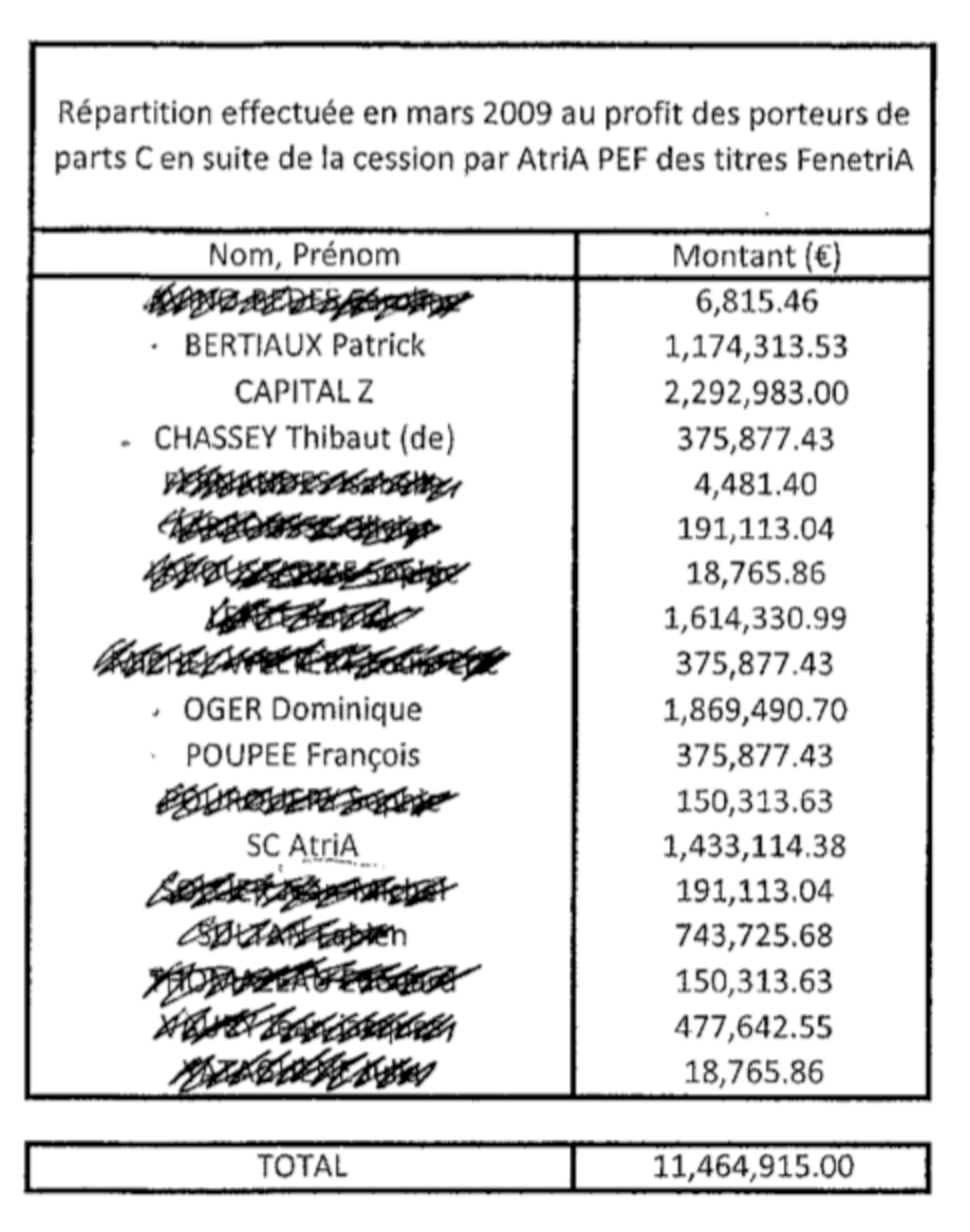

As we have seen, once an investment adds value of 8% a year, the fund's managers are entitled to 20% of the capital gain in the form of something financial circles call ‘carried interest'. And this is what happened in this particular case: when in 2009 Atria's managers sold the asset, which they had bought six years earlier for 12 million euros, at a price of 60 million euros - selling half to themselves and half to Pragma - they realised a fantastic capital gain of 48 million euros. These managers therefore benefitted from a colossal carried interest of 11.464 million euros. The three members of Atria's executive committee thus shared out nearly 3.5 million euros between them. Of this sum, 1.8 million euros went to executive committee chairman Dominique Oger, 300,000 euros to Thibaut de Buretel de Chassey and more than 1.1 million euros to Patrick Bertiaux.

Click on the document to enlarge

Enlargement : Illustration 6

These figures can be found in Annex 28 of the expert's report, shown above. (The names left visible are of those who Mediapart has been able to ascertain played a role in the affair; the others, Atria employees, have been hidden.)

This little windfall is even juicier when one considers that French tax rules are very accommodating for financial revenues. While salaries are subject to income tax with a top marginal rate of 40%, excluding general social security contributions and the CSG, a specific social security contribution, which are also deducted from salaries. But carried interest is treated more favourably: the 2009 draft finance bill called for its taxation to be brought in line with that for gains from transferable securities which is 30.1% including deduction of the CSG.

In addition, in this table of beneficiaries of carried interest we can also see that an entity called SC Atria also benefitted to the tune of 1.4 million euros. Mediapart sources indicate that this carried interest comes for the most part from rights owned by Pragma's managers, worth 1.198 million euros.

The independent investors who came in to back APEF3 in buying the asset in question from APEF1, and whose presence was supposed to guarantee that the transaction was above board, earned a packet for themselves because they had a share in the capital gain made by APEF1.

The parties involved argue there is no reason to contest the transaction. Questioned by Mediapart (their position can also be read in full by using the ‘Prolonger' tab found at the top of the pages of this article), their comments included the following: "Carried interest is inherent to the profession of being an investor. Funds all over the world use it, and in particular, it aligns the interests of the management team with those of investors in the fund. Regarding our own position, the shares in the carried interest held by us were sold prior to the transaction, and at a lower price than would have been the case had we held these shares until the transaction was carried out." They added that in any case, obtaining a report from an independent expert was sufficient for abiding by the fund's rules.

Californian teachers' retirement fund saw 'major conflict'

Atria chairman Dominique Oger said: "Atria observes the highest possible standards in terms of adhering to rules governing professional ethics" As for Pragma, it observed that "its two managers sold their shares in the carried interest, which they had held since 1999, to SC Atria at a 25% discount and before the transaction was carried out. Therefore everything was done with the strictest possible observance of the rules, without the slightest conflict of interest."

However, the events are a little more complicated than that. Although the two Pragma managers sold their shares in the carried interest just before the transaction, they only received payment afterwards. Annex 25 of the expert's report shows that the two Pragma managers were paid for the sale of their rights in the carried interest "25% in April 2009 and the remainder in September 2009" - although the asset transfer transaction in question was completed in March 2009. Therefore it can be simply resumed that both transactions, the asset transfer and the sale of shares in the carried interest, were carried out in a coordinated and simultaneous manner.

Graver still is the fact that the head of Atria, Dominique Oger, called a meeting of APEF3's advisory committee on February 12, 2009, which was a legal obligation, to approve the transaction. But during this committee meeting the identity of the supposedly independent investor was not revealed, as can be seen in the minutes of the meeting which figure in the expert's reports reproduced below, and which can be downloaded here.

To enlarge the document, click on Fullscreen.

These minutes constitute a valuable document. Firstly, they reveal that numerous members of the advisory committee, who are among the fund's investors, were aware that this transaction posed unusually serious problems of conflict of interest. Among these were CalSTRS, the Californian state teachers' retirement system, the largest teachers' retirement fund in the US and the country's second-largest public pension fund, which ended up voting against the plan, and stressed in the minutes that it saw "the current situation as posing a major conflict of interest for the management company because the team would receive a large sum in carried interest from APEF1 as part of the proposed transaction."

A little later during the meeting, the minutes show, there was even a premonitory exchange: the representative of a British fund, Pantheon Ventures, "reminded the team that the investment will be closely examined by the investors". The minuted reply says: "The team confirms that it is aware that its reputation is more at risk with this transaction than with any other planned investment."

Despite this, not once during the whole meeting was the name of the co-investor mentioned. There was only a remark from the representative of Axa Private Equity, Vincent Gombault, who "asked the team to confirm that the new investor accepts the price and that it is completely independent from Atria." The minutes note: "The team confirms these points."

Clearly, the advisory committee did not know that the third party investor was Pragma, and was far from being informed that Pragma had rights to a share of the carried interest obtained by Atria in its capacity as the manager of APEF1, the fund selling the asset in question.

Dominique Oger appears not to understand why this could cause astonishment. "We answered all the questions that were put to us at the advisory committee. We had two potential candidates in the running at the time of the meeting, both were third parties," he told Mediapart.

Yet again, the matter is far more complex than that. Because the AFIC's code of conduct (available again here) is very clear. Article 5 lays down the following: "Members must do everything to avoid finding themselves in a situation of conflict of interest, whether with another member, with a partner company or with investors, and also to avoid conflicts that could arise between investors and companies. All members should manage their business in the interests of investors, with the intention of acting fairly in relation to partner companies or co-investors. Members who exercise several activities are obliged to set up rules and procedures that allow them to foresee, detect and manage conflicts of interest. A member may have direct and significant financial interests in companies in direct competition with each other simultaneously, on condition that they have previously informed the companies concerned."

Article 8 adds: "Members must observe the principle of transparency towards investors at all times and supply them, in the context of the duty to inform, and as frequently as necessary, with information on the development of the business, the billing of fees paid directly or indirectly to companies that may be linked directly or indirectly, the risks involved and the methods used to deal with potential conflicts of interest."

Even if he was never asked the question, should not Atria's head have told his advisory committee that his friends in Pragma received a share of the carried interest, lest he infringe this Article 8? The question weighs even more heavily because it is precisely the issue that precipitated the tension in relations between Atria and Massena before they became embittered and ended in legal action. Massena asked Atria several times who the third party investor was, but never obtained a reply.

"From the very first day [in February 2009] Massena asked again and again for the name of the third party investor," said Jean-Pierre Versini-Campinchi, Massena's legal counsel. "For months it did not obtain a reply. When Massena was finally informed [in July 2009], it raised the question of independence and received assurances on this."

"A year later [April 2010] these were invalidated when a director of Atria who had been ousted provided Massena with an affidavit that showed - as has since been recognised - that two of the directors of the third party investor had had a personal financial interest in the fund making the sale."

The expert's report provides de facto confirmation that more than a year after the transaction, Atria had still not disclosed the fact that the two Pragma managers had an interest in the sale. Massena had to make repeated requests before the expert sought and obtained the necessary documents.

Axa voices tardy reservations

The question posed here is whether the actions of asset manager Atria involved any major wrongdoing. Surprisingly, its main ally, Axa Private Equity, has recently begun to query the transaction.

Certainly, the company's number two, Vincent Gombault, maintains his confrontational stance towards Massena. He swears by his ‘bible' that is the profession's worldwide code of professional conduct, the Private Equity Principles - it can be downloaded here - that he has not infringed it even once. He believes that Massena is fighting a rather different battle.

"In this period of financial crisis, Massena is just seeking pretexts for pulling out and recovering its initial investment. There are no other reasons for these groundless accusations against Atria. Yes, false accusations, since to my knowledge all the rules were respected, I made sure of that since an independent evaluation of the price was held," he said.

Massena wrote a letter to Dominique Sénéquier, head of Axa Private Equity, on October 1, 2010 (available here). The letter angered her counsel, William Bourdon, who even says he is now considering a lawsuit for blackmail and attempted extortion.

Vincent Gombault added: "Given this, it is true that I did not know the identity of the co-investor until after the transaction, and I only discovered then that this investor had owned rights to a share of the carried interest."

Asked by Mediapart whether, if he had known before hand, would he have taken the same decision in the advisory committee, Gombault replied: "Probably not. It wouldn't have changed the fact that an expert's report on the pricing was carried out and that the transaction was therefore proper both from a regulatory and technical point of view. But from an ethical point of view, it would have led me to look more closely at the situation. Different options could have been envisaged."

So, was the transaction shocking from an ethical point of view but proper in regulatory terms? In fact, a meticulous reading of the rules laid down by the French stock exchange regulatory authority, l'Autorité des Marchés Financiers (AMF), or of certain clauses in the legal and regulatory framework for the financial industry in France, the Code Monétaire et Financier, suggest a different interpretation.

In the first instance, Articles 313-18 and 313-19 of the AMF's general regulations (they can be downloaded here) place an obligation on providers of investment services to take "all reasonable measures to ensure that situations where there is conflict of interest are detected." And among potential situations of conflict of interest, it identifies one such case as being where "the provider (...) is likely to realise a financial gain or avoid a financial loss at the expense of the client."

This rule is the logical extension of Article L214-3 of the Code Monétaire et Financier (available here in French only), which sets a rule that is absolutely critical for the business of risk capital funds and asset management companies: for "Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities, the depositary and the management company must act exclusively for the benefit of subscribers."

In the light of these provisions, the story takes on a new dimension, and not only for Atria but also for Pragma. As Maurice Lantourne, Pragma's lawyer, stressed in a letter to Mediapart, (please see ‘Prolonger' tab at top of this page), in a legal sense, Pragma "is not part of the lawsuit involving Massena and Atria." But Pragma's managers nonetheless took part in the transaction in question without informing their own investors that they had pocketed part of the carried interest.

Whatever, when Massena's managers took exception to these practices in 2009, they got very little support. Indeed, they sent the expert's report to all of Atria's major investors: Axa Private Equity, IDI Invest (which last year bought up AGF Private Equity), Amundi (majority-owned by Crédit Agricole); as well as to other reputable investors like Fondinvest, Finava or Caisse des Dépôts. But none of them took action.

However, the dispute has taken a significant development now that the matter is to come before the Paris Commercial Court and an appeal has been lodged with the AMF (click here to consult the lawsuit, made available to Mediapart by a manager from Massena). Other major foreign funds that invest in Atria, like the Britain's Pantheon Financial , LGT of Lichtenstein or Calstrs, the California teachers' pension fund, may not entirely appreciate the somewhat accommodating and frankly opaque practices carried out in Paris.

The moral of this investment fund saga is surely this: France has adopted the bad habit of copying the most dubious free-market practices of countries like the US and Britain, especially when they allow operators to rake in vast fortunes in no time at all, but it has shown no haste to import the regulations and transparency that usually accompany that form of capitalism.

This gives French business the worst, most worrying image possible, that of a jungle where anything goes. And, as is often the case in Paris's rather incestuous capitalism, it has tacit government blessing. Atria's chairman, Dominique Oger, was made a Knight of the Légion d'Honneur, France's highest civil honour, on July 14th, 2010, after he was nominated for the decoration by the former French Secretary of State for Commerce and Small Trades, Hervé Novelli.

-------------------------