The Grand Palais in Paris is hosting an exceptional exhibition of major modern artworks from the widely scattered collection of the celebrated Stein family of art patrons who settled in the French capital from the US in the early 20th century. The stunning show of works by Renoir, Cézanne, Picasso, Matisse, Manguin and Bonnard - to name but a few - is the fruit of five years of dogged detective work by specialists in France and from the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. Joseph Confavreux talks to the team behind this unprecedented worldwide treasure hunt.

-------------------------

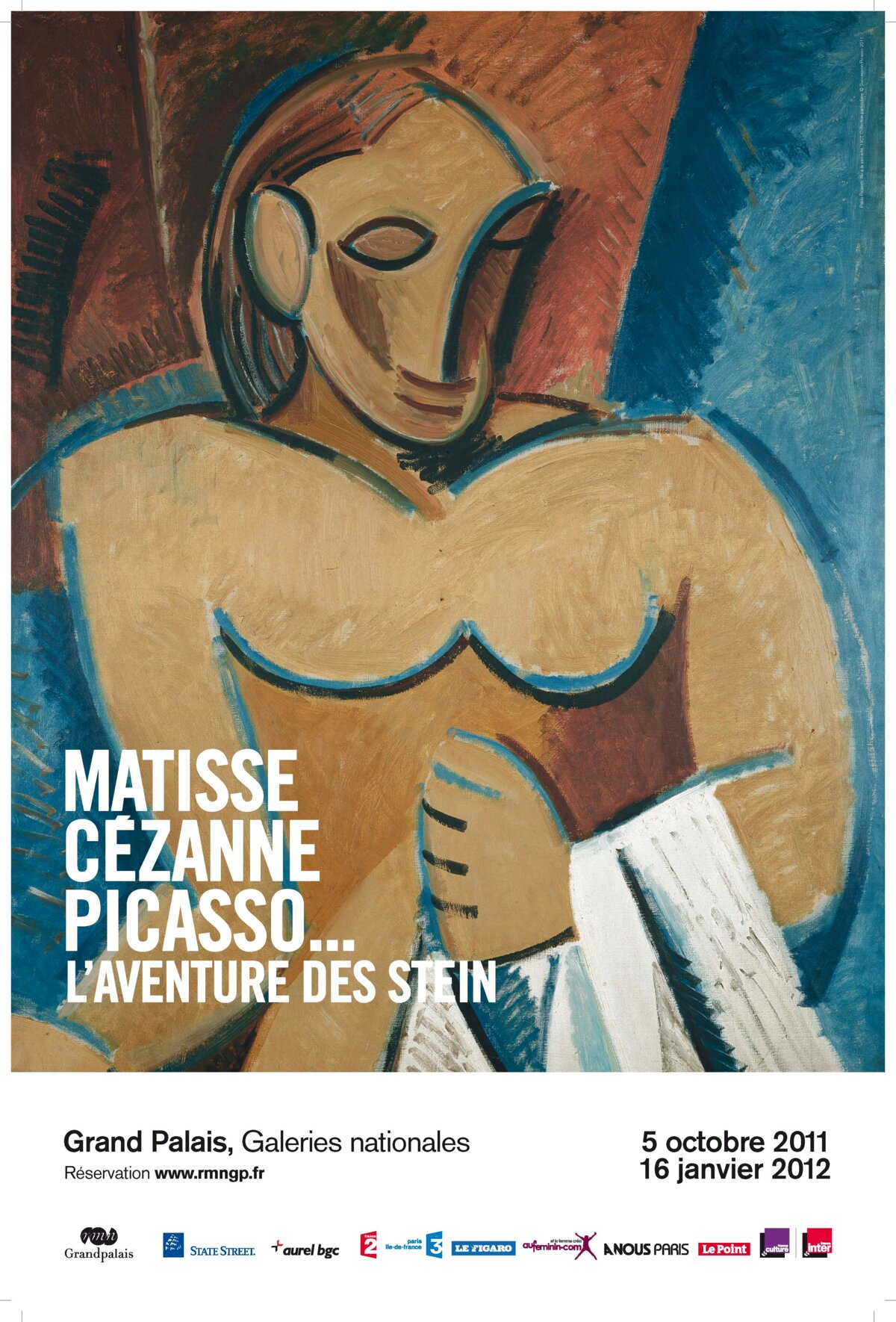

The paintings, drawings and documents in the exhibition ‘Matisse, Cézanne, Picasso... The Stein Family' that opened this month at the Grand Palais in Paris were scattered during the lifetimes and after the deaths of the Stein brothers and sisters, escaping inventory, and changing hands throughout the 20th century. Reunited after five years of research by US and French specialists, they now form one of the most important modern art collections in the world.

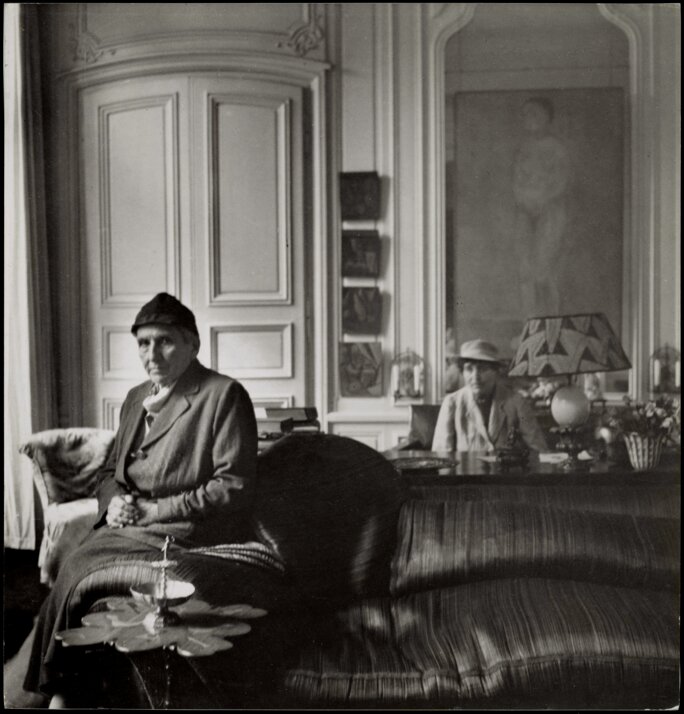

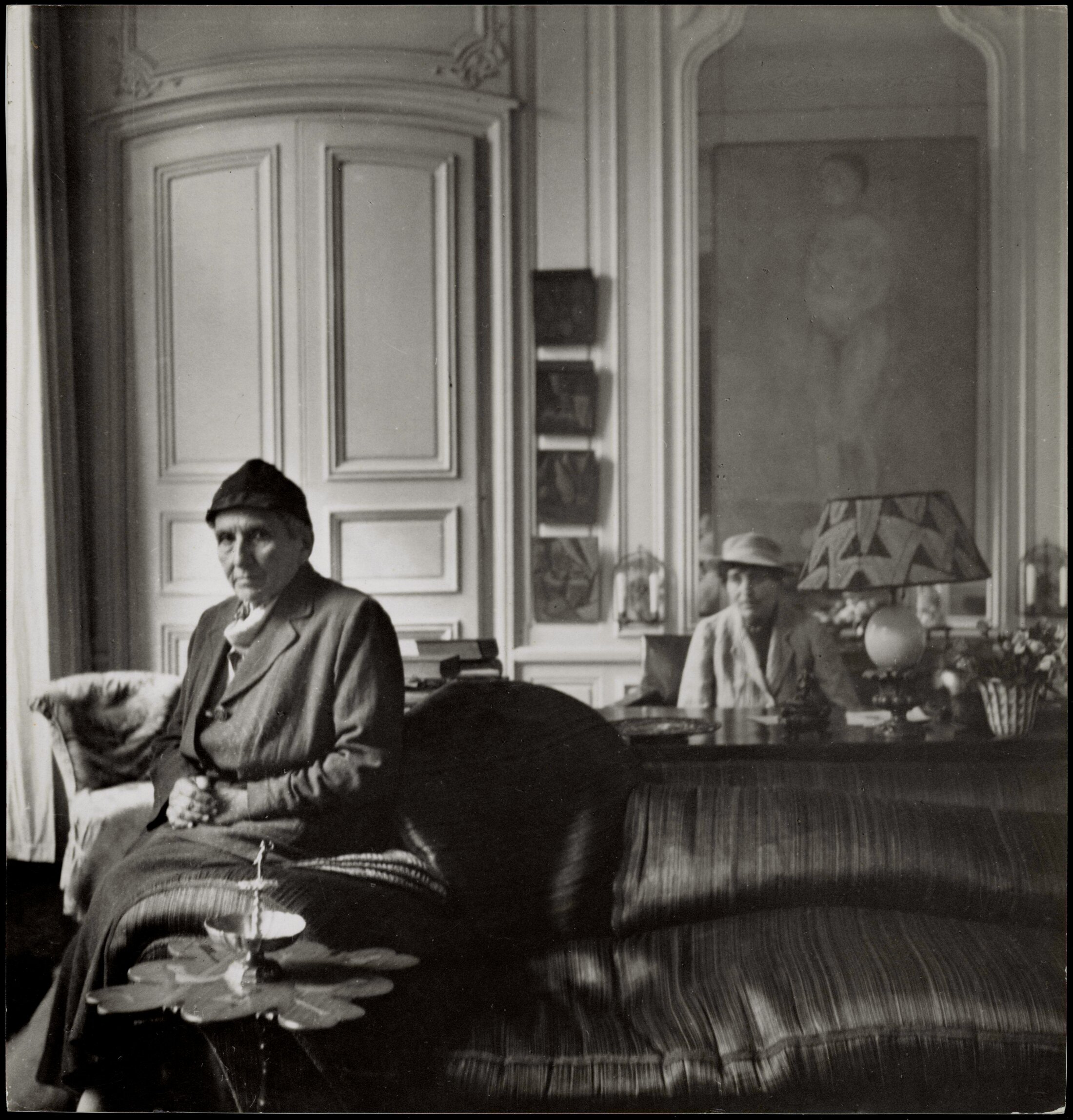

Perception of modern art in Europe, and then in America, was sculpted in a major way by writer Gertrude Stein, her brothers Leo and Michael, and Michael's wife Sarah. The exhibition displays the works acquired in the course of the Steins' exceptional adventures and include several masterpieces, some of which have rarely been seen in France.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Following the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) and before the New York Metropolitan, the Grand Palais in Paris is paying tribute to these visionary patrons of the arts, who spotted then little-known painters such as Matisse and Picasso and astutely connected works, artists and collectors.

But behind the visual pleasure of discovering certain paintings, and understanding the significance of the collection at a crucial point in the history of painting, is an unprecedented work of investigation and research. "Exhibitions like these are increasingly rare," stresses Cécilie Debray, the curator of the Parisian version of the exhibition. "It's the fruit of a major international collaboration of a kind we see very little of nowadays."

The San Francisco MOMA, the Grand Palais in Paris and the New York Met shared the preparatory work and financing of the project. "I think we were innovative in terms of sharing data, information," points out Carrie Pilto, an American who was, on the US West Coast, the lynchpin of the project, working alongside the curator of the San Francisco MOMA, Janet Bishop. "I'm thinking for example of the moment when the curator of the Metropolitan, Rebecca Rabinow, told us about a letter she had found among Gertrude Stein's papers at Yale University. Her brother Michael mentioned in it a "cloisonné pot" that Matisse had borrowed from them in order to paint a canvas he had to send to Munich. I remembered a photo in the archives of our museum, dating back to 1962, of a Japanese pot, and I managed to locate it with friends of the Stein family in San Franciso. A picture search then allowed us to find this object faithfully represented in the middle of the Matisse painting in the Munich Pinakothek der Moderne." The pot is now exhibited at the Grand Palais, alongside the works by Matisse who, for his inspiration, often borrowed objects kept by Sarah Stein, particularly pieces from the East.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Thus the three institutions joined forces and pooled their research resources for an exceptional collective project, in order to assemble the pieces of a puzzle - an endeavour played out on a global, art-historical scale. "We shared out the artists, because on a project like this you need to work closely with the ‘Picassoists' and the ‘Matissists'. And we did the same with individual collectors," explains Cécile Debray. "I focused on Gertrude, San Francisco on Michael and Sarah, who were the first to go back to the States, and the Metropolitan on Leo".

'There were never 600 works together at the Steins'

Enlargement : Illustration 3

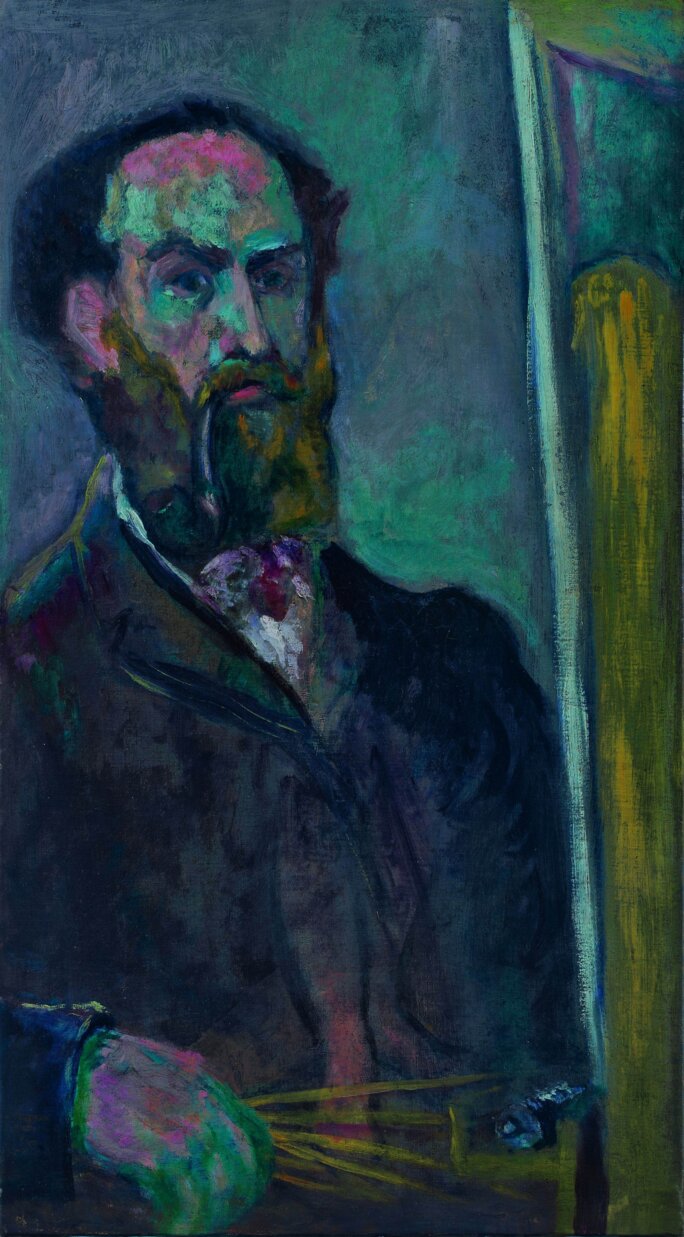

The starting point for this resurrection of the Stein collection is also its cornerstone: La Femme au chapeau (Woman with a Hat), by Matisse (pictured right), a fundamental work for the Fauvist movement, shown in the Autumn Salon of 1905, which was held over a century ago in the very same Grand Palais where the collection has been reassembled today.

Leo Stein, the first member of this Jewish American family to move to Paris at the beginning of the 20th century, bought it thanks to family income from investments in tramways and real estate in San Francisco. Thus began the Stein's acquisition of canvases signed by young painters such as Matisse, or a certain Spaniard just starting to exhibit in Paris, Pablo Picasso. This Woman with a Hat, later taken to the United States by Michael and Sarah worried by the rise of fascism in Europe, ended up in the hands of a friend of the couple's, who gave it to the San Francisco MOMA in 1990. The idea of an exhibition sprang from that donation.

Sleeves were rolled up and work began, becoming more and more vertiginous as the researchers and curators who had embarked on the adventure became aware of the scope of all the paintings and drawings that had passed, at one time or another, through the Steins' hands. "In 2007, I was employed for an exhibition initially scheduled for 2009," remembers Pilto. "In the end more than two extra years were needed." Pilto, who spent a long time in France, explained that she worked from a "bible", the 1970 exhibition catalogue entitled Four Americans in Paris.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

After the death of Alice B. Toklas, the companion and legatee of Gertrude Stein, her works, acquired by a consortium of collectors from the MoMA in New York, were indeed exhibited in 1970 with numerous pieces from Michael and Sarah's collection. "But this catalogue included only 250 references, sometimes very brief, without any images, such as ‘Matisse, Tree, 1898?', or ‘Picasso, Nude, 1906'", says Carrie Pilto. It was therefore necessary to work, for five years, from "letters, photographic archives, dealers' inventories," adds Cécile Debray.

The task was complicated by the fact that the Steins, notably Leo, had a relaxed attitude to their collection. "They bought, they sold, according to their discoveries and desires," explains Debray. "There were never 600 works at any one time at the Steins', even though a large number of masterpieces did feature on their walls."

The Stein collection was constantly renewed in the lifetime of the brothers and sisters, and then scattered after their death, notably to indulge the costly passion for racehorses of David, the grandson of Sarah and Michael.

Hence the paintings found themselves all over the world: Hiroshima, Sao Paolo, Copenhagen, Madrid... a dispersion increased by the dispute between Gertrude and Leo Stein, each going off with part of the collection, never to see each other again. Sarah and Michael's ill fortune didn't help either. At Matisse's instigation they lent several of their key pieces to the Gurlitt gallery in Berlin for the painter's solo exhibition. It was the summer of 1914, the war was to start a month later, and they would never see the works again.

Negotiating with 100 lenders

The work of listing and assembling the maximum number of pieces from the Stein collection was therefore riddled with pitfalls.

"For example, for a long time I got stuck on a little painting that could be seen in a photo of the living room of the rue Madame," explains Carrie Pilto. "We couldn't see much more than a black rectangle, because of the quality of the photo and dimensions of the painting. After a few weeks I said to myself, if this painting seems so black, could it simply be that it's the representation of a black figure? It could therefore be a Gauguin or a Picasso, and leafing through dozens of books on Gauguin, zooming in on the photo, I managed to identify a portrait of a Tahitian woman that we didn't know had passed through the Michael and Sarah Stein collection. It was all the more interesting for possibly being the sister of the very beautiful portrait of a Tahitian man owned by Matisse, giving a new example of the symbiotic dynamic between the painter and his collectors. But though I was able to list it in the inventory, it wasn't, unfortunately, possible to actually find the canvas."

Enlargement : Illustration 5

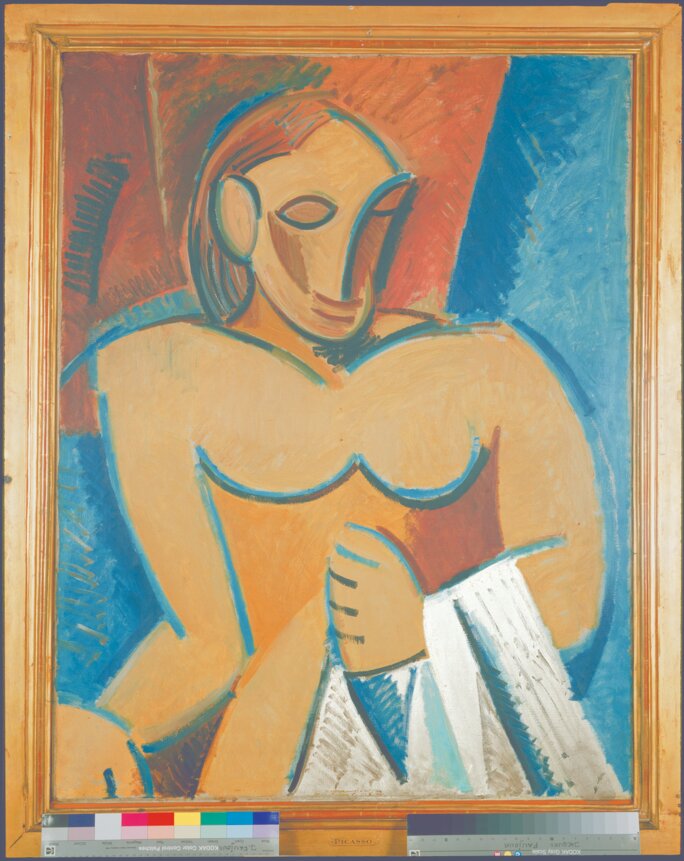

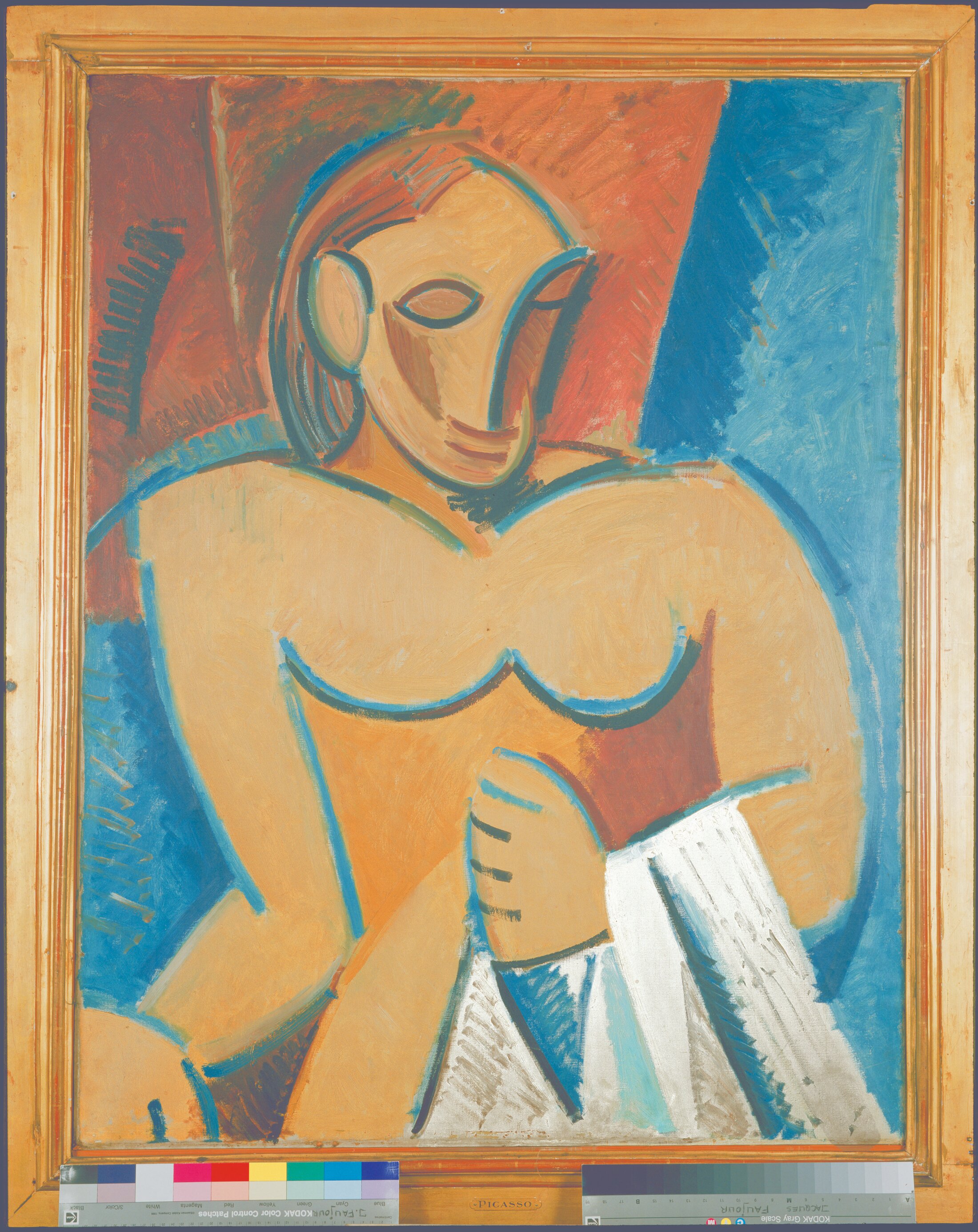

Cécile Debray evokes the case of the Nu à la serviette (Nude with Towel) by Pablo Picasso (pictured right). Invisible for years, it adorns the cover of the French version of the Grand Palais exhibition catalogue and poster. "It took us a long time to identify it, because it didn't feature on any of the photos of the Stein's home. And for a long time we confused it with the Nu à la draperie, at the Hermitage museum in Saint Petersburg, which never belonged to the Steins."

It is also this painstaking, meticulous work, combined with a lucky star, that allowed the notes taken by Sarah Stein at the Académie Matisse to be found. These offer exclusive insight into the work and teaching of the painter, which could otherwise have ended up in the rubbish bin. "I remember, it was February 2009, I was on the trail of Daniel Stein, one of Sarah and Michael's grandsons, and I learnt that he had just died, in December 2008," explains Carrie Pilto. "He had bequeathed his house and its entire contents to a long-term neighbour and friend, who was about to empty it for renovation work. We went there with Janet Bishop and he gave us access to rarely-opened boxes, which were full of photos and family documents." These included albums showing daily life at Le Corbusier's Villa Stein-De Monzie, and the bundle of letters Gertrude Stein had sent the family during her 1934 tour of America. "Above all," continues Pilto, "in the office, hidden away behind modern books, there was Sarah's precious notebook."

Enlargement : Illustration 6

This quest for works that had passed through the Stein collection also required infinite negotiations to convince over a hundred lenders. Some of them were intransigent. The major collection belonging to Dr Barnes, who had acquired numerous pieces belonging to Leo Stein, didn't receive an exit visa, in accordance with the Barnes Foundation statutes. But for the rest, "it was also five years of diplomatic ballet" smiles Cécile Debray.

Such an effort for the inventory, to be found in its entirety in the American catalogue, wasn't however simply intended to be exhaustive. "To simply show a collection isn't necessarily exciting," comments Cécile Febray. "What I wanted to capture, and this is possible with the Steins, is how a collection could be a resource for reflecting on art. Leo Stein opened the eyes of Americans to modern art. He made the connection between the impressionists - Manet, Renoir, Cézanne, Degas - and the paintings of Picasso and Matisse. He prefigured what was to become MOMA's approach. This exhibition isn't just a collection of works of art, it makes sense".

The curator of the Grand Palais exhibition also recalls how the friendship of Gertrude Stein and Pablo Picasso nourished the writing of the one and the painting of the other, though Gertrude Stein does embellish a part of the story, saying it took 83 sittings for Picasso to paint her portrait, which was the only one the writer donated to a museum in her lifetime.

The role of the Stein collectors wasn't therefore limited to the purchasing of canvases. In a letter exhibited at the Grand Palais, Picasso asked to see the Gauguins owned by the Steins, and Matisse was able to contemplate Cézannes hung in a bohemian fashion on the walls of the rue de Fleurus and rue Madame residences in Paris. The Stein adventure not only enriched, painting by painting, an exceptional collection, it has also influenced our ways of seeing.

-------------------------

English version: Chloé Baker(Editing by Graham Tearse)

-------------------------

The exhibition 'Matisse, Cézanne, Picasso...The Stein Family' is on at the Grand Palais in Paris until January 16th. (Metro station: Champs-Elysées-Clemenceau).

Open Friday- Monday from 9 a.m. to 11 p.m., Tuesdays from 9 a.m. to 2 p.m., Wednesdays from 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. and Thursdays from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. Entrance fee: 12 euros, under-13s free.