It was about 4pm on July 15th 2015, a warm and sunny day, when Mohamed Abrini, a Belgian from the Molenbeek district of Brussels where he had recently sold his snack bar, arrived as agreed in front of a pizzeria in the Small Heath area of the British city of Birmingham. It was close to a local park, where members of the local Muslim community often prey when the weather allows.

Just a few days earlier, Abrini had left Syria.

Abrini, of Moroccan descent, spoke into his phone in a mixture of English and Arabic, two languages that he spoke with difficulty. The person he was talking with told him to wait for a man dressed in a blue top and three-quarter-length trousers.

Abrini had arrived at Heathrow airport on July 9th on a flight from Istanbul. He spent the four days between July 10th and 13th shopping in London, before travelling to Birmingham where he took photographs around the city, notably the back of the central New Street railway station, and hung around the casino. Abrini, who was arrested in Belgium the following year, would explain that, “I am a gambler, it’s my vice, I play roulette, poker and one-armed bandits”.

He held numerous phone conversations with a man who had sent him on several occasions to the park in Small Heath, and each time the appointment was finally called off, which he later explained was a way of checking he wasn’t being followed. He would subsequently learn that it was also to make sure he was who he was supposed to be and not an undercover police officer.

That afternoon on July 15th Abrini had waited about ten minutes before a dark-skinned man with a blue top, his head covered by its hood and, despite the heat, his face obscured by a scarf , approached him. At a distance he indicated to Abrini to follow him. Separated by about ten metres, they walked through Small Heath Park, then crossed a bridge over the nearby A45 motorway and entered some woodland where a third man – who had no beard, moustache or disguise –was waiting. Abrini would later explain: “I began by speaking in Arabic and he said to me that it was OK, I could speak in French.”

The third man handed Abrini a bag and the meeting was quickly over. The Belgian left the woodland, back the way he came, and made for his hotel. Over the following days Abrini continued with his travels, including a visit to the Manchester United football club’s ground Old Trafford where he also took pictures of the stadium. Abrini was an avowed supporter of Spanish club Barcelona.

On his WhatsApp profile is a photo in which Abrini can be seen giving a thumbs-up beside two street entertainers who are disguised as Marvel comics hero Iron Man. In the photo is a cash collection bucket with a price marked up in pounds, and in the background is an advert in English. On July 16th Abrini, a man unknown to intelligence services and with no criminal record, left Britain, slipping away as invisible as he had arrived.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

It was much later when the West Midlands Police Counter Terrorism Unit, one of five teams that form the national UK Counter Terrorism policing Network, became interested in his sojourn in Birmingham, when the two men he met in Small Heath, members of a local Islamist cell, were identified and arrested. They were accused of handing £3,000 (about 3,800 euros) to Abrini who, the police established, had also been in contact during his stay in Britain with Abdelhamid Abaaoud, a childhood friend who had become a senior figure in the Islamic State group (IS). Abaaoud was suspected of being one of the principal planners of the November 2015 attacks in Paris (and who was killed by French police several days later).

Abrini had taken precautions before his trip. He had asked his-brother-in-law in Belgium to keep a record of five phone numbers which he did not want to be discovered in case of his arrest in Britain. These included numbers which connected with warehouses in Turkey where on-site guards were able to make contact with Abaaoud.

It was in April 2016 that Abrini was arrested in Belgium for his role in the terrorist bombings Brussels in March that year. He was filmed on CCTV cameras pushing a luggage trolley containing a suitcase bomb at Brussels’ Zaventem airport on March 22nd 2016, alongside two of the suicide bombers and half-hidden behind sunglasses and a hat. Following his arrest, British counter-terrorism police assisted his questioning by the Belgian colleagues. Abrini admitted travelling to Syria in June 2015, which he said was to visit the grave of his younger brother who had been killed in combat there. He said that while there, Abdelhamid Abaaoud had given him the task of collecting money he was owed by the men he met in Birmingham. The claim was placed in doubt given that Abaaoud gave Arbrini 2,000 US dollars to make the trip, which would have left little change against the money supposedly owed. The British police concluded that he had in fact made the trip to carry out reconnaissance.

In compiling this report, Mediapart has had access to numerous documents, many of which are cited here. These include statements, both from suspects and witnesses, and documents from intelligence services, notably, but not only, the French internal and external services, respectively the DGSI and the DGSE, which are directly cited here. Mediapart has also interviewed officials from security services and former jihadists. This report also draws on research by third-party organisations, referenced in their comments below.

In an IS video claiming responsibility for the November 13th 2015 terrorist shootings and bombings in and around Paris, which left 130 people dead and another 368 wounded, it also threatened attacks in Britain – threats which were illustrated with images of then British prime minister David Cameron and also the British parliament. A report by the French internal intelligence service, the DGSI, reported that the threat was “very credible” and that, “Along with France and Belgium, the United Kingdom featured among the priority targets of Abdelhamid Abaaoud during the summer of 2015”.

Under questioning, Mohamed Abrini insisted that he did not travel to Britain in July 2015 to prepare terrorist attacks. In his statement he said: “Neither in London, nor Birmingham nor Manchester did I carry out reconnaissance in connection with the preparing of terrorist attacks […] There is no plan aimed at England as a potential target of a terrorist act. From what I know, it’s France that is the sworn enemy of the Islamic State. I think that England has secret services that are more developed, better in the practice of observation and so on. Therefore more difficult to hit. I haven’t had contact either with English nationals in Syria.”

Concerning his photographing of the Old Trafford football stadium in Manchester, he added: “I had nothing to do so I went by the [Manchester United] football stadium.” He said an Algerian national who worked in a hookah bar spoke to him about “visits, activities that went on” at the Manchester United ground. “So I visited the stadium and took photos,” he said, insisting: “I have played football all my life […] I was not carrying out reconnaissance.”

In a separate statement, given just a few days earlier, Abrini had referred to the connection that could be made between his visit to Old Trafford and the Paris attacks in November 2015 when, along with the mass shootings at the Bataclan music hall and of customers of Paris cafés, suicide bombers also attacked the Stade de France sports stadium. “Even if you can make a link between the attacks in Paris – the stadium in Paris and the photos of the stadium in Manchester, I confirm that it [Editor’s note: the visit to Old Trafford] did not involve reconnaissance,” his statement read. “It was pure tourism.”

But Abrini’s insistence that he was an innocent man unknowingly caught up in a web of terrorism by a childhood friend does not stand up to examination. Indeed, as French daily Le Monde revealed earlier this year, shortly before he arrived in Britain one of Abrini’s mobile phones had been in contact with Réda Hame, a French member of IS who was arrested in the summer of 2015 in France where, he admitted under questioning, he had been sent from Syria by Abaaoud to commit an attack against a concert hall.

As for the suggestion by Abrini that he had travelled to Syria to visit his brother’s grave, a report by the French internal intelligence service, the DGSI, found that he had stayed for several months within IS-controlled territory in Syria, between December 2014 and May 2015.

Shortly after the November 13th 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris, Nicolas Moreau (see page 1 of the first report in this series) asked to be re-questioned by the DGSI. The repentant French jihadist had been first interrogated by the DGSI after his arrest in June that year on his return to France from Syria where he had joined the ranks of IS. But now, Moreau, who was raised in France by a couple from the town of Nantes after they adopted him from an orphanage in South Korea, offered information about two men which he said would be the “jackpot” for the DGSI because “you will avoid terrorist actions” in the future.

The men Moreau offered information about were “Abu Souleymane” and an accomplice, both from Brussels and of Moroccan origins, and both members of what Moreau called “the Islamic State’s external secret services”. He said neither took part in combat on the frontline, nor would they be called to carry out suicide bombings, such was their importance to the IS group. He described them as “true professionals in melting into the crowd”. They are tasked with buying weapons and, more generally, looking after “organization and logistics”.

“They won’t directly carry out an attack, but they will ensure it’s a success,” said Moreau. During his subsequent trial in December 2016 and January 2017, when he was sentenced to 10 years in prison for criminal association with a terrorist group, the true identity of the man who went by the nom de guerre Abu Souleymane emerged; it was Mohamed Abrini. Souleymane was the first name of his deceased younger brother.

After Abrini’s arrest in Belgium in April 2016, he partially revealed his loyalties under questioning by a Belgian examining magistrate. He tried to justify the actions of IS which was made up, he said, of “people who wanted to defend the people who were being massacred”, “to defend widows and orphans”, adding: “Of course there are other things. That’s life madam,” he told the magistrate. “It’s not Alice in Wonderland.” The “other things” he referred to were terrorist attacks in which IS carried out in its war against what it calls “the crusaders”.

One month after the IS murdered by decapitation US hostage James Foley, a senior IS figure who was reportedly acting as a double agent for the British intelligence, Abu Ubeida, was himself executed by IS – although there remain doubts as to the certainty of his death (see pages 4 and 5 in the second of this series of reports). The IS spokesman, Sheikh Abu Mohamed al-Adnani, officially declared the group’s war on Westerners on September 22nd 2014. In a vitriolic address to jihadists following the coalition air strikes against IS that began in August that year, he said: “If you can kill an American or European non-believer, in particular the nasty and dirty French […], then count upon Allah and kill them in any manner […] Hit his head with a stone, cut his throat with a knife, run over him with his car, throw him from a high place, strangle him or poison him.”

In reality, IS had long been preparing to make just such a call on jihadists to mobilize, but until then the DGSI considered that evidence of violent actions ordered by IS had not been “demonstrated”. IS never claimed responsibility for the shooting attack on the Brussels Jewish Museum on May 24th 2014, carried out by one of its members, Mehdi Nemmouche, when four people were killed in what was the first of its terrorist actions in Europe. After Nemmouche was arrested one week later, he was found in possession of a video recording intended to be used for the purpose of claiming responsibility, which began with a picture of a flag on which was written, in Arabic, “Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant”. Five months before the Brussles attack, Nemmouche, then in Turkey, held a 24-minute phone call with Abdelhamid Abaaoud.

In a phone call made on July 5th 2013, which was tapped, a French jihadist who served as Abu Ubeida’s bodyguard spoke with another jihadist who had returned to France. The bodyguard spoke of Nemmouche, who was beside him in Syria, telling his correspondent in France that “finally, his [Nemmouche’s] thing is delayed for very much later, you understand?”. At one point, the bodyguard hands Nemmouche his phone. “Everything that I told you, almost everything, has auto-cancelled itself [...] Everything we talked about [...], there’s no real date, you see,” he tells the correspondent in France, who asked: “It stays the same but it’s just put off, is that it?” Nemmouche answered: “Yeah, but it could be put back far, you understand what I mean?”.

Two weeks later, the bodyguard for Abu Ubeida had another phone conversation, again tapped, with an Islamist friend who had remained in France without joining the jihad in the Middle East. The bodyguard infers that the project of sending jihadists to carry out terrorist actions in Europe had been approved by the highest authorities of the fledgling IS group. The bodyguard asked his friend if he knew of “someone who makes false passports”, to which the other replied, “It’s costly”, mentioning the price of 5,000 euros. “That doesn’t matter, it’s an order from the emir of the believers,” replied the bodyguard, in an apparent reference to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the group’s leader, and future self-declared caliph.

After his release, former IS hostage Federico Motka, an Italian aid worker held hostage by the group between March 2013 and May 2014, told Italian investigators that an IS interrogator asked he and other hostages held with him “lots of questions about the refugees who sought asylum in Europe, he wanted to know how the procedure worked”.

Clearly, one year before the beginning of coalition airstrikes against IS, and therefore one year before Abu Mohamed al-Adnani’s call to jihadists to murder Westerners, the group was already laying plans to send jihadist killers to Europe. The branch of IS that was in charge of preparing such actions and all clandestine operations outside the group’s self-declared caliphate was Amn Al-Kharji, a section of its secret service, the Amniyat.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The public recognition by IS of the existence of its secret service came only after the March 2016 bombings in Brussels, when its statement in Arabic claiming responsibility for the attacks, which claimed the lives of 32 people, said the perpetrators belonged to a mafraza amniyya, meaning a “security detachment”. When, in May 2016, the group claimed responsibility for the simultaneous bomb attacks on the Syrian coastal towns of Jableh and Tartus, which killed 184 people, it spoke of the role played by members of “the Amniyat”.

Following the shooting attack on a police van on the Champs-Elysées avenue on April 20th 2017, which left one officer dead, one of the IS propaganda websites, Rumiyah, took pains to explain that if the perpetrator had the surname al-Beljiki, meaning “the Belgian”, it said it was a “codename” used for “security reasons” in the attacker’s conversations with “his case officer”, otherwise known as a “handler”.

***

In a document entitled “The five pillars of global jihad”, the DGSE, France’s external intelligence service, describes “a particularly flexible” operating mode allowed to jihadist killers. “Substantial room for manoeuvre appears to be left to the discretion of this kind of assailant in terms of targets (concerts, trains, stations, synagogues, churches, café terraces etc.), of timing and mode of operation,” it noted.

The repented French jihadist Nicolas Moreau described the process by which the Amniyat would consider propositions from jihadists for terror attacks. “They look to see if you’re not burnt in your country, if you can be trusted,” he said under questioning. He said it was Abu Omar al-Soussi – the nom de guerre of Abdelhamid Abaaoud, in a reference to the Sousse Valley in Morocco from where his family had its origins – who had “a look in” on such proposals, but that “two Tunisians” who had the final word on agreeing to them or not.

It described the IS process of mounting exterior operations: “Initial training in Syriaof a group of volunteers; a selection of individuals who are to be infiltrated in Europe and to then work isolated from each other while waiting the signal to move into action (sleeper cell): supply of necessary logistical support from local cells, which themselves are activated, independently of the operational actors, from Syria.”

In Raqqa, a pool of jihadists who were designated to carry out terrorist attacks had been formed in the space of just a few months, described by Réda Hame, arrested in France in 2015 after he had been sent from Syria to carry out an attack, as a “proper factory”. Former DGSI head Patrick Calvar, speaking while he was still in the job before a French parliamentary committee of enquiry in May 2016, insisted a new “dimension” in terrorist operations had come about. “The organisation which, today, plans attacks on European soil is made up of professionals [...] totally accustomed to clandestine conditions and who, in the past, have already demonstrated their know-how,” he said.

On January 9th 2015, Amedy Coulibaly attacked a kosher supermarket, Hyper Cacher, on the south-east tip of Paris taking customers and staff hostage, shooting dead four of them. He claimed to be acting in the name of IS. During the several hours of the hostage-taking, before he was finally killed by police when they stormed the building, RTL radio managed to reach him by phone. In the ensuing interview, he warned: “Others like me will come, and there will be more and more.”

Amedy Coulibaly, who did not try to join the jihad in Syria, perhaps because he was already previously on the radar of the French justice system for terrorist-related activity (an attempt to break out an Islamist from prison in 2013), knew what he was talking about with that threat.

Coulibaly attacked the Hyper Kasher store two days after the January 7th 2015 attack against the satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo, when brothers Chérif and Saïd Kouachi shot 12 people dead and wounded 11 others, claiming to act for Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). Coulibaly had the next day shot and killed a trainee policewoman in a Paris suburb, before mounting his attack the following day on the kosher supermarket. He was killed when police simultaneously stormed the kosher store and the printers’ shop, north of Paris, where the Kouachi brothers had found refuge. The attacks by Coulibaly and the Kouachi brothers were coordinated.

Coulibaly was in direct contact with IS, which on January 7th, the day of the attack on Charlie Hebdo, sent a message which was later found on a computer belonging to him. In code-like style, he received a message from IS saying, “Indications soon fr find friends to help you”. On January 8th, another message arrived: “Not possible friends, work on alone”. Until now, the French intelligence services have still not been able to identify the person, or persons, who sent the messages.

“We know that there is the cyber-criminality police who monitor all the connections,” said Swedish jihadist Osama Krayem, questioned by a Belgian magistrate after his arrest in April 2016 on suspicion of being involved in the March 2016 bombings in Brussels.”We didn’t take such a risk. [...] In the field of terrorism, contacts are made through encrypted means.”

The Amniyat had a specialist in secure communications. According to statements from Réda Hame, questioned by the DGSI, that person was an Anglophone “Black”, who had “short braids” and who wore “a cap back-to-front”. Hame said the specialist gave jihadist terror operatives a memory stick that contained software for encryption, which erased data records of internet connections, and which contained passwords and IDs used to communicate with the Amniyat on websites. “It worked like a dead letter box,” said Hame. In espionage jargon, a dead letter box is a place where messages and other material can be left and collected without the operative or his handler ever meeting.

Video games also offer an opportunity for clandestine conversation, as apparently was the case with the Kouachi brothers. When already under surveillance in 2012, a DGSI report said Saïd Kouachi “spends a large part of his time playing video games online with his brother Chérif”. The pair was particularly fond of Call of Duty, a wargame popular among jihadists. It offered the advantage of allowing participants to chat amongst themselves without being listened to. A December 2016 report into the workings of the Amniyat by the US-based International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism also said that IS operatives communicate via video game chat networks.

The IS however warns its operatives against using the iPhone, nicknamed “the spy-phone”, and also against using phones in hotel rooms because of the risk of bugging. It also advises that outside conversations should always be conducted with a hand obscuring the mouth, and to use coded nicknames about subjects discussed, such as “cheese” for France, “kebab” for Turkey, “pizza” for Italy and “hamburger” for the US.

But in general, IS operatives are, as one western intelligence IT specialist put it, “disciplined, they master coded messages with an encrypted key, they are practically untraceable”.

***

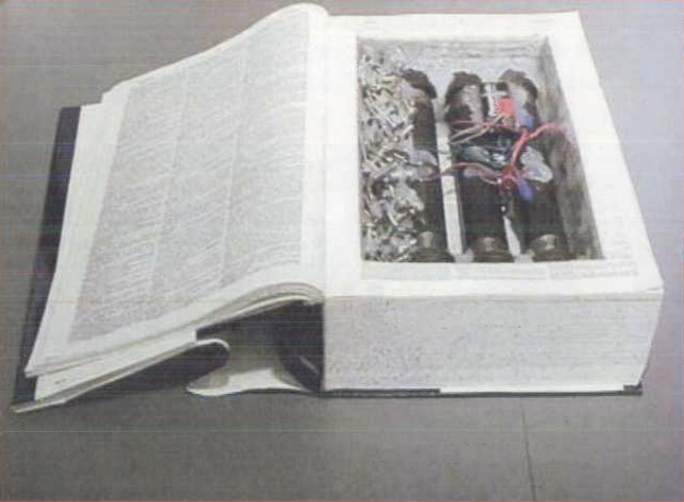

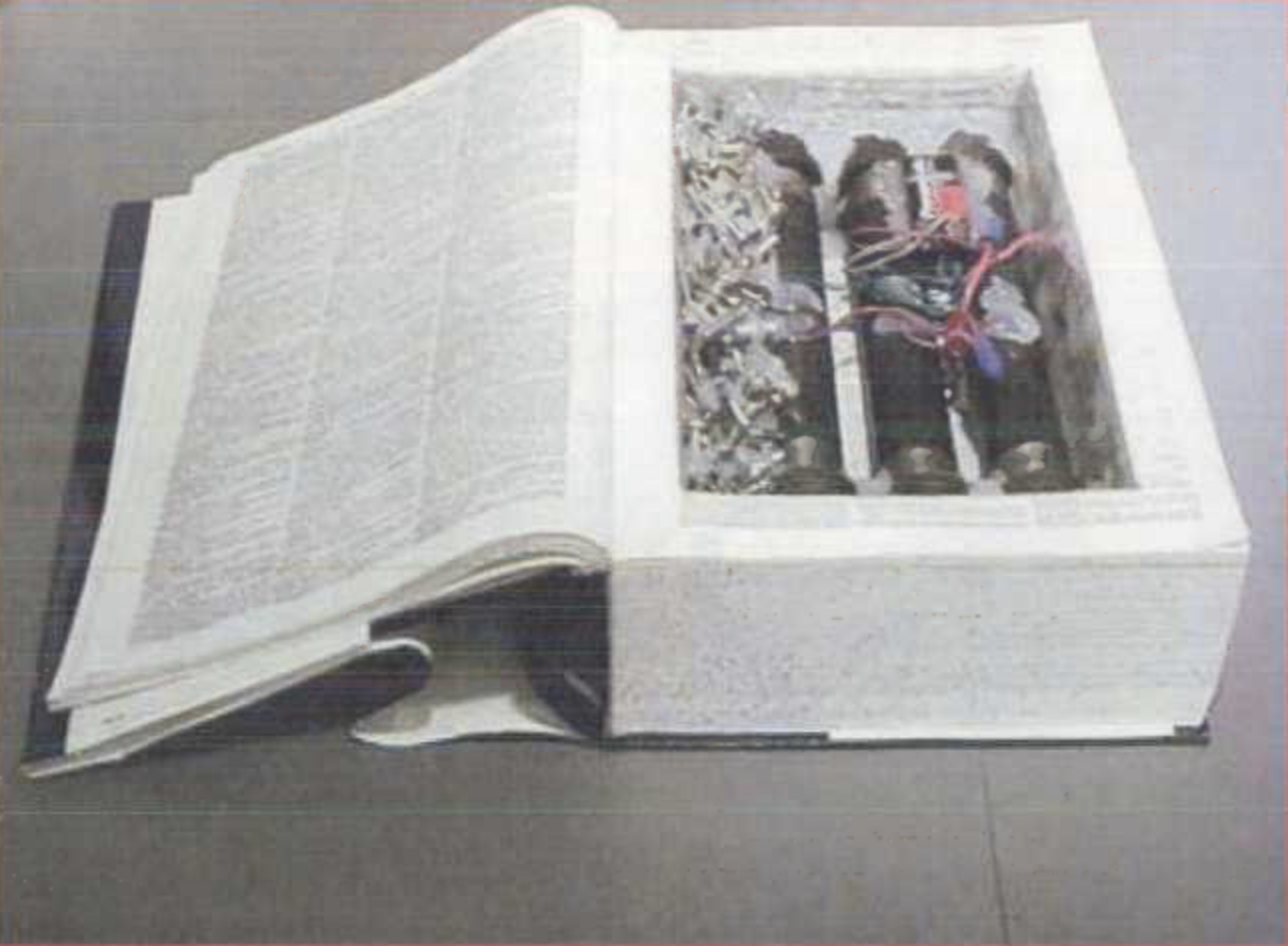

In 2011, two jihadists of dual French-Tunisian nationality were arrested as they separately their way back to France from an al-Qaeda training camp situated close to the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan. One was arrested in Turkey the other in Bulgaria. Inside the watches of both were found tiny memory cards that contained 50 videos, 2,500 images and 250 documents explaining how to prepare explosive weapons, from mines to suicide belts, how to booby-trap vehicles and to transform mobile phones into detonators.

On March 25th 2016, three days after the bombings of Brussels airport and an underground train, Algerian national and IS member Abderrahmane Ameuroud, 39, was arrested at at a tramway station in the Belgian capital. Ameuroud was a veteran jihadist, who was jailed in France in 2005 for having provided logistical help for the assassination of Ahmad Shah Massoud, the powerful Afghan political and military leader, head of the Northern Alliance who, after playing a major part in the Afghan resistance to Soviet occupation in the 1980s, later fought against the Taliban during the civil war in the country. Massoud died from his injuries sustained in a suicide bomb attack on September 9th 2001when he was being interviewed by a group masquerading as a television crew. The assassination was later regarded as connected to the September 11th terrorist attacks in the US, and it is speculated that it was ordered by al-Qaeda leader Osama Bin Laden.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Ameuroud’s arrest was a dramatic scene; he was shot in the leg by police and as he lay on the ground a robot device was used to secure a rucksack he was carrying. Police initially feared the rucksack contained explosives – Ameroud was suspected of having been trained 15 years earlier in Afghanistan in the handling explosives – or even toxic gas because of the strong odours that seeped from it. Finally, it transpired that it contained phials of excrement, but why is still unclear.

***

Nasser al-Bahri, a former bodyguard for bin Laden, wrote a book (co-authored by French journalist Georges Malbrunot) about his experiences in al-Quaeda, which was first published in French in 2010 under the title Dans l’ombre de Ben Laden – “In the shadow of Bin Laden” – and which was later published in English entitled Guarding Bin Laden: My life in al-Qaeda. Writing about the training camps in Afghanistan during the 1990s, al-Bahri recalled: “We spent whole days studying the habits of our targets,” adding that there were course on “How to change the features of [our] faces? How to address neighbours of the target?”. Al-Bahri said all new recruits followed such training, which included learning how to “write coded letters”.

Senior al-Qaeda operative Anas al-Libi (real name Nazih Abdul-Hamed al-Ruqai) was captured in his native Libya in October 2013 by US commandos and sent for trial in New York for his alleged leading role in the 1998 bombing of US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania which killed 224 people. He died from liver disease in January 2015 before the start of his trial.

In the year 2000 in the British city of Manchester, where he was then living after being granted asylum as an opponent to Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi, police carried out a search of his home. On his computer they found a file containing an al-Qaeda training manual, which included two separate chapters dedicated to “espionage” and “security”. This very complete manual included advice for jihadists on leaving their home country, how to act in countries they transit through, and how to behave upon arriving in Pakistan.

Much later, the Kouachi brothers and Toulouse gunman Mohamed Merah, who in a spree of attacks in the southern French city in March 2012 shot dead seven people including an 8-year-old Jewish girl, all attended al-Qaeda camps abroad, escaping arrest along the way. In 2010, the first edition of al-Qaeda’s online magazine Inspire offered jihadists advice on how to get through airport security controls. During the summer of 2015, Inspire published what it called “a military analysis” of the Kouachi brothers’ attack on the Paris offices of Charlie Hebdo in January that year and which claimed the lives of 12 people. It described the massacre as a successful “special intelligence operation”, detailing why this was so.

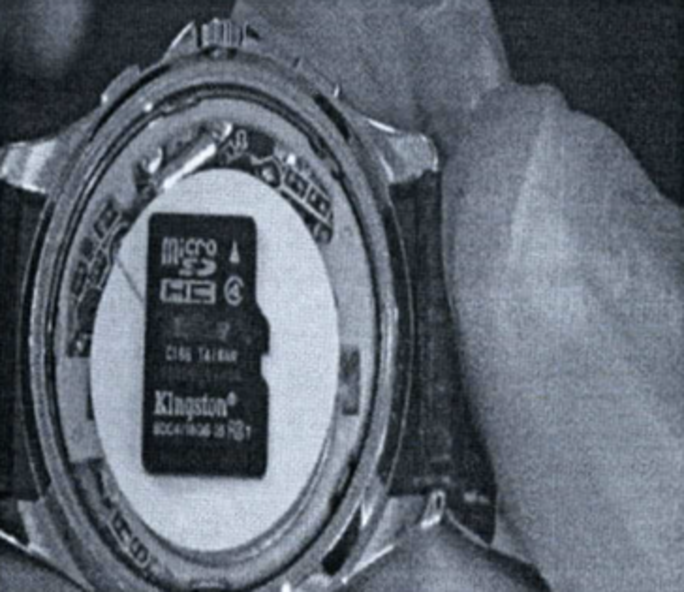

Also in 2015, a 70-page jihadist manual entitled How to Survive in the West was published on the internet. "This book is a guide for the Muslims who are living in a majority non Muslim land," it read. "It will teach you how to be a secret Agent who lives a double life, something Muslims will have to do to survive in the coming years." It advises watching the Jason Bourne series in order to learn how to escape being followed, and recommends carrying out attacks in countries worst-hit by the economic crisis because their intelligence and security means are supposedly depleted. It even forecast that the recession across the Western world would result in weakening counter-terrorism services, which will become saturated.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

“Since more than 30 years, there exists technical literature that’s put about which doensn’t concern the way of carrying out an attack but [rather] how to protect oneself from the intelligence services,” said former DGSE official Yves Trotignon, who now works as a consultant on risk analysis and also teaches at the Paris political sciences school Sciences-Po. The Islamic State publications are very specialised. Dabiq [Editor’s note: an IS online publication] dedicated six pages explaining how to protect data on iPhone and Android. Al-Naba [an IS online newsletter] writes articles with illustrations on how IMSI catchers [mobile phone tracking surveillance devices] work, how drone attacks are carried out.”

Numerous petty methods are employed by jihadists to appear uninvolved in religion. In an interview with Mediapart two years ago, a man previously convicted of terrorism-related activity explained how he would empty a beer can and fill it with apple juice to pretend to police that he was no longer a militant Islamist. There was also the case of a group in France who planned to finance their journey to join up with jihadists abroad by armed robbery, and who advised, in the event that they were caught, to tell the police that they had “met in a night club” and that they did not take part in prayers. Jihadist manuals advise shaving off beards, using scent, what dress colours to use and above all to avoid wearing a watch on the right hand – a tradition among mujahedeen.

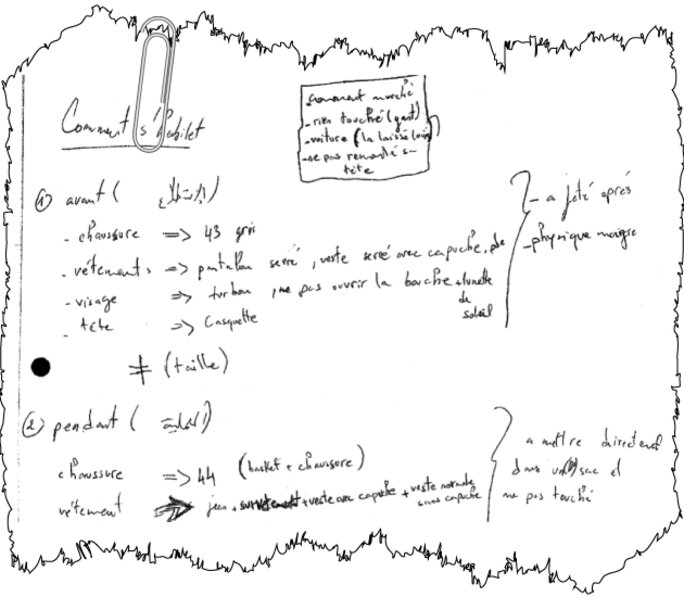

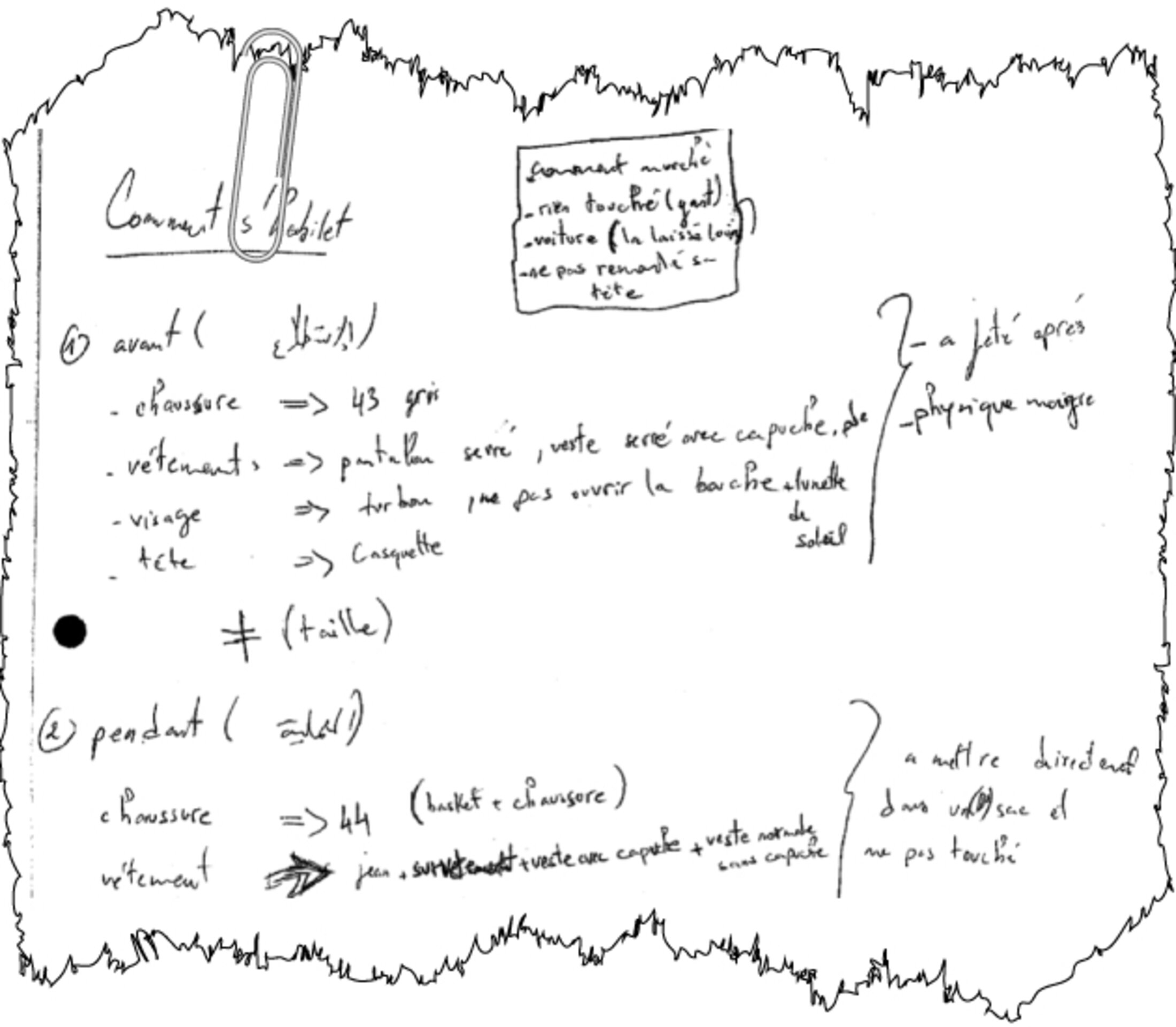

On April 19th 2015, Sid Ahmed Ghlam, a 24-year-old computer student of Algerian origin, was arrested after he apparently accidentally shot himself in the leg during his alleged preparations to attack two churches in the southern Paris suburb of Villejuif . The body of a 31-year-old woman was found in her car nearby, shot dead at point-blank range in what is believed to be an attempt by Ghlam to hi-jack her vehicle. Ghlam’s Renault Mégane car was later found on a car park in another Paris suburb, Aulnay-sous-Bois, containing weapons and bullet-proof vests. But among the objects in the car was also a 27-page document. A police report noted that this featured, “A succession of lists of technical, and even tactical, acts to be carried out before, during and after the fulfilment [of the attack]”. Indicating that the sites of CCTV cameras should be carefully referenced, it advised Ghlam on “how to dress” – for example, that he should wear grey shoes in French size 43 during the days before the attack, swapping to size 44 trainers when carrying out the attack.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Under questioning following his arrest in April 2016, Mohamed Abrini recalled: “In all the safehouses there were wigs […] It was gross, but apparently the grosser it was the better it worked.”

***

On the evening of January 12th 2015, “ Pashtun”, a former Brussels tramway driver, was the target of a Belgian police surveillance operation. He was a member of an IS cell that was lying dormant in Verviers, a suburb of Liège, while awaiting orders from Abdelhamid Abaaoud. It was just days after the attacks in Paris against Charlie Hebdo magazine and the Hyper Cacher kosher supermarket. French investigators suspected that the cell could have been the “friends” that Amedy Coulibaly, who attacked the Hyper Cacher store, was expecting help from in his two-day shooting spree.

According to a DGSI document, the jihadist cell planned to attack “police stations on Belgian territory”, adding that during its investigation “it appeared that members of the cell were well used to clandestine conditions and multiplied security measures” which, further on in the report, were described as “rudimentary” but which “complicated” investigations. “They regularly changed vehicles and mobile phones, while using coded language. They also had instructions to show no exterior signs of radicalisation,” it said.

During the trial earlier this year of members of two jihadist cells that operated together – one based in Cannes in southern France, the other in Torcy, east of Paris – in preparing terrorist attacks and organizing departures for Syria, a police officer told the court how one of the jihadists was “well-experienced” in countering tailing operations. “He would take off through red lights, use one-way streets [driving the wrong way], make several tours of a roundabout,” he said. In a raid on one of the jihadists’ homes, police found a list of cars with their makes and colours. Under questioning, the jihadist explained that, “I thought they were those of the police who were watching me”.

***

In an attempt to avoid the arrest of the cell in Verviers, Abdelhamid Abaaoud, who had set up a temporary base in Athens, ordered one of the jihadists to cut off relations with “Pashtun”, and decided that another of them, who was also too vulnerable, should be transferred to another “team”. A Belgian police report noted that the Verviers group were “very suspicious, even paranoid” about being followed. “They appear to be aware of the possibility that the police localize their car, and talk about the necessary verifications to be made to ensure that is not the case (take a torchlight to check underneath’),” it read.

On January 15th 2015, Belgian security forces stormed the cell in Verviers, shooting dead two members and rounding up the rest. Abdelhamid Abaaoud narrowly escaped arrest when police raided the apartment he was staying in Athens. Greek investigators found on his computer hard drive evidence of a plan to attack an airport.

Swedish jihadist Osama Krayem was arrested in Belgium, along with Abrini and three others, on April 8th 2016. He was recorded on CCTV footage on March 22nd 2016 in Brussels, alongside one of the suicide bombers, Khaled el-Bakraoui, shortly before the latter detonated his explosive charge at the Maalbeek metro station causing the deaths of 18 people. Krayem was also seen on CCTV footage buying rucksacks used that same day in the suicide bombings at Brussels airport which killed 32 people.

Six months before his arrest, Krayem was in an IS hideout in Schaerbeek, Brussels, situated on the rue Henri-Bergé. He was with Ibrahim el-Bakraoui, brother of Khaled. It is believed it was the first time the two men had met. El-Bakraoui, who appears to have wielded a certain authority over Krayem, asked the Swede to carry out a reconnaissance mission at Amsterdam’s Schiphol airport. Krayem, who considred himself a “soldier” for IS, was reluctant but followed El- Bakraoui’s instructions. “It was to go and see if, at the airport, there were luggage lockers […] of a certain volume,” he later explained.

El-Bakraoui was a hardened criminal, who in 2010 shot and wounded a policeman during a robbery in Brussels. Under questioning, Krayem would later describe the El-Bakraoui brothers as “the big bosses” of the IS sleeper cell. Neither lived at the address on the rue Henri-Bergé. “Like any boss in a business, a boss always has a place for himself and a place for those who work for him,” said Krayem. “It’s to avoid attracting attention to them.”

Ibrahim used his personal computer, and had contact with all the members of the cell who he gave orders to, rather than conversations with. “There’s a hierarchy,” said Krayem. “Someone gives orders and others carry them out. Nobody can do anything out of initiative, he must receive orders from Islamic State.”

The coach tickets for Krayem and an accomplice who was to join him on the 200-kilometre journey to Amsterdam were bought that night, using cash. The other members of the cell living on the rue Henri-Bergé were not made aware of the mission. Krayem would claim that he had no idea what the purpose of it was.

In most intelligence activities, agents have only partial knowledge of an operation that involves a whole team. A recent jihadist document available on the internet explains how separating information given to members of a cell can avoid the risk of a whole network being dismantled. Sometimes, even the senior member is kept in the dark.

“I was there to carry out an attack,” explained, under questioning, Ayoub el-Khazzani whose attempted attack on passengers in the Amsterdam-Brussels-Paris Thalys train in August 2015 was thwarted by three Americans travelling to Paris. “But I say clearly to you that I didn’t know myself what I was to do,” the Moroccan continued in his statement. He explained that Abdelhamid Abaaoud, who commanded him and who had accompanied him on his journey from Syria to Belgium, “told me nothing”, adding: “On the Wednesday he told me that the target was in the Thalys, where I was to attack Americans.” Two days later he boarded the train to carry out the attack.

“These networks are very compartmentalized,” said Bernard Bajolet, then DGSE boss, speaking before the aforementioned French parliamentary commission last year. He said certain failures by the security services were explained by that fact, which meant that “even when we know an attack is going to happen, however well we know the names of the terrorists, we can’t always prevent it”.

When Krayem boarded the coach to Amsterdam, he was off the radar of European intelligence services, despite the fact that he had been engaged in combat in Syria. He was travelling with false Belgian ID papers, and when he was subject to a control at the Dutch border he was waved on. When he reached the airport he strolled around it for two hours without finding any baggage lockers. Back in Schaerbeek that same evening, he briefed Ibrahim el-Bakraoui.

***

The afternoon before Krayem left for Amsterdam, Mohamed Abrini had watched while a group of childhood friends in the Belgian town of Charleroi filled a Seat car with weapons and explosives, wrapped in plastic. Abrini climbed into a Renault Clio, carrying nothing illegal, to head off in convoy with the Seat behind. One of his friends had fitted the Clio with a radio jammer, to block out eventual monitoring. Abrini's role was to act as a scout for any trouble ahead, staying in permanent phone contact with the occupants of the second car.

***

Protected from possible eavesdropping, and driving to the accompaniment of Islamic chants on their stereos, what Abrini later dubbed as “the convoy of death” travelled straight to the Paris region. “I was sick of things, sad, because I knew it was over,” he later said under questioning. “I was accompanying my friends during their last breath. I know that all of those guys were going to die.”

Abrini said that once they had arrived at a small rented house in the Paris suburb of Bobigny, he was nervous, unlike the others. “They were calm, peaceful,” he later said in a statement. “They prepared something to eat in the kitchen, watched television. I saw no stress in them.” He recalled how, when it soon came to the time for him to leave, he hugged Abdelhamid Abaaoud in the garden behind the house. “”Really, it was very hard,” he said. Abaaoud “was sad and I was crying”. Abrini would later find excuses for the murderous acts committed by his friends.”They know that it’s France which bombs them ceaselessly, which bombs schools,” he argued, adding that, “for them their dead [their victims in France] have no more value than the dead of them [in Syria]”.

Abrini left that night by taxi. The cost of the trip back to Brussels was 365 euros. He went back to the rue Henri-Bergé in Schaerbeek. The next day, November 13th 2015, Krayem would leave for Amsterdam and that evening, beginning at around 9.15 pm, the mission of what Abrini called ‘the convoy of death” would begin in Paris, when suicide bombers and gunmen claimed the lives of 130 people – including 89 at the Bataclan music hall – and wounded more than 400 others.

-------------------------

- The French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse