It was early in the afternoon on Wednesday when a boat fishing close to the French port of Calais alerted the French regional surveillance and rescue centre (CROSS) at Cap Gris-Nez that it could see several people in the cold waters.

As a rescue operation immediately got underway, one of those sent to the scene by the CROSS was Charles Devos, a voluntary lifeboat operator with 43 years’ experience. “We picked up six dead people, one of who was a pregnant woman,” he said, visibly shocked at what he had seen. “We picked up more and more migrants during our rescue efforts. I always said to my colleagues that ‘It’s going to end up in tragedy’. There it is, it’s today. It’s happened.”

According to the latest official toll on Thursday, the bodies of 27 people, including three children and seven women, one of who was pregnant, had been retrieved. Meanwhile, two survivors, both of them men, were in a critical condition in a hospital in Calais. Precisely how many people in all were in the boat when it left the French shore is still unknown.

The boat, a long inflatable dinghy with no rigid underbelly, was deflated when its remains were brought ashore. “When you see container ships, 300-metres long, or 200-metre-long car ferries, you can tell yourself that alongside those, an inflatable doesn’t count for much in the water,” added Devos. The Channel, and notably the 35-kilometre-wide strait between Calais and Dover, the narrowest point between France and Britain, is one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world.

While an investigation into the tragedy is underway in France, led by magistrates based at the inter-regional specialised judicial services (JIRS) based in the city of Lille, there is speculation that the migrants’ overcrowded dinghy was either hit by a large boat, or took on water due to its weight.

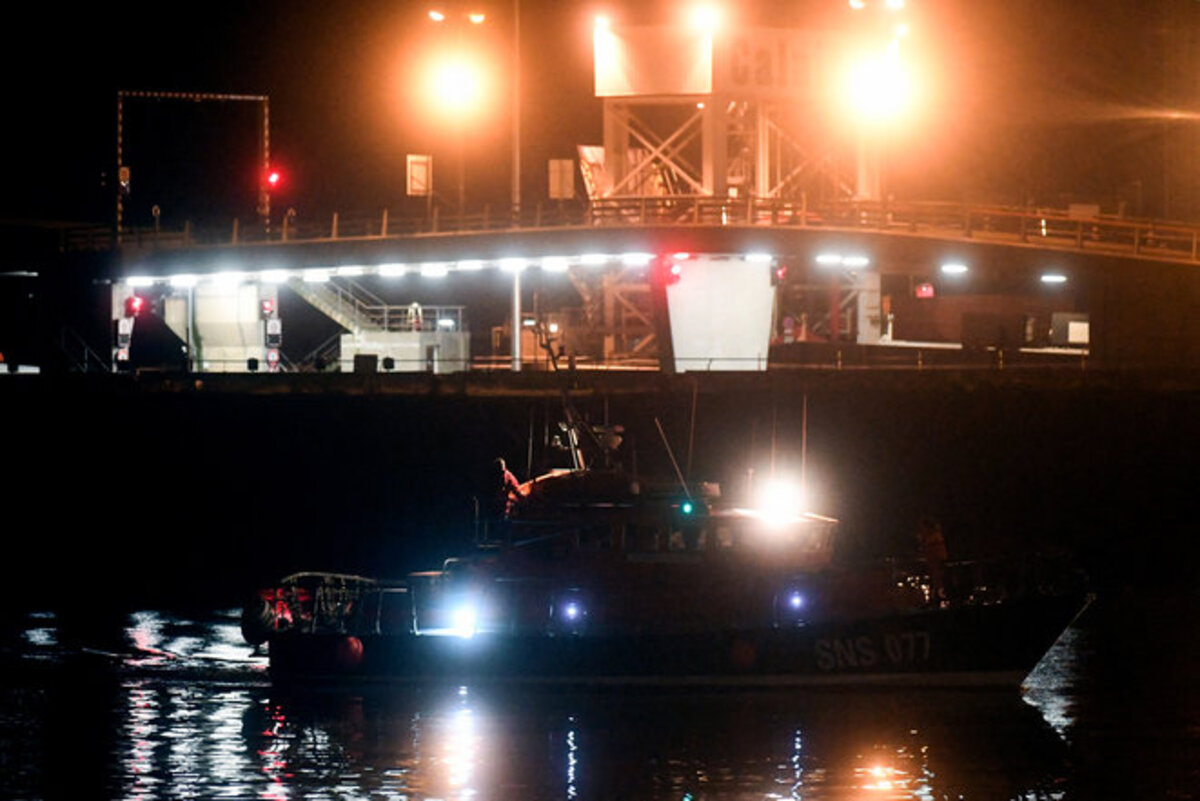

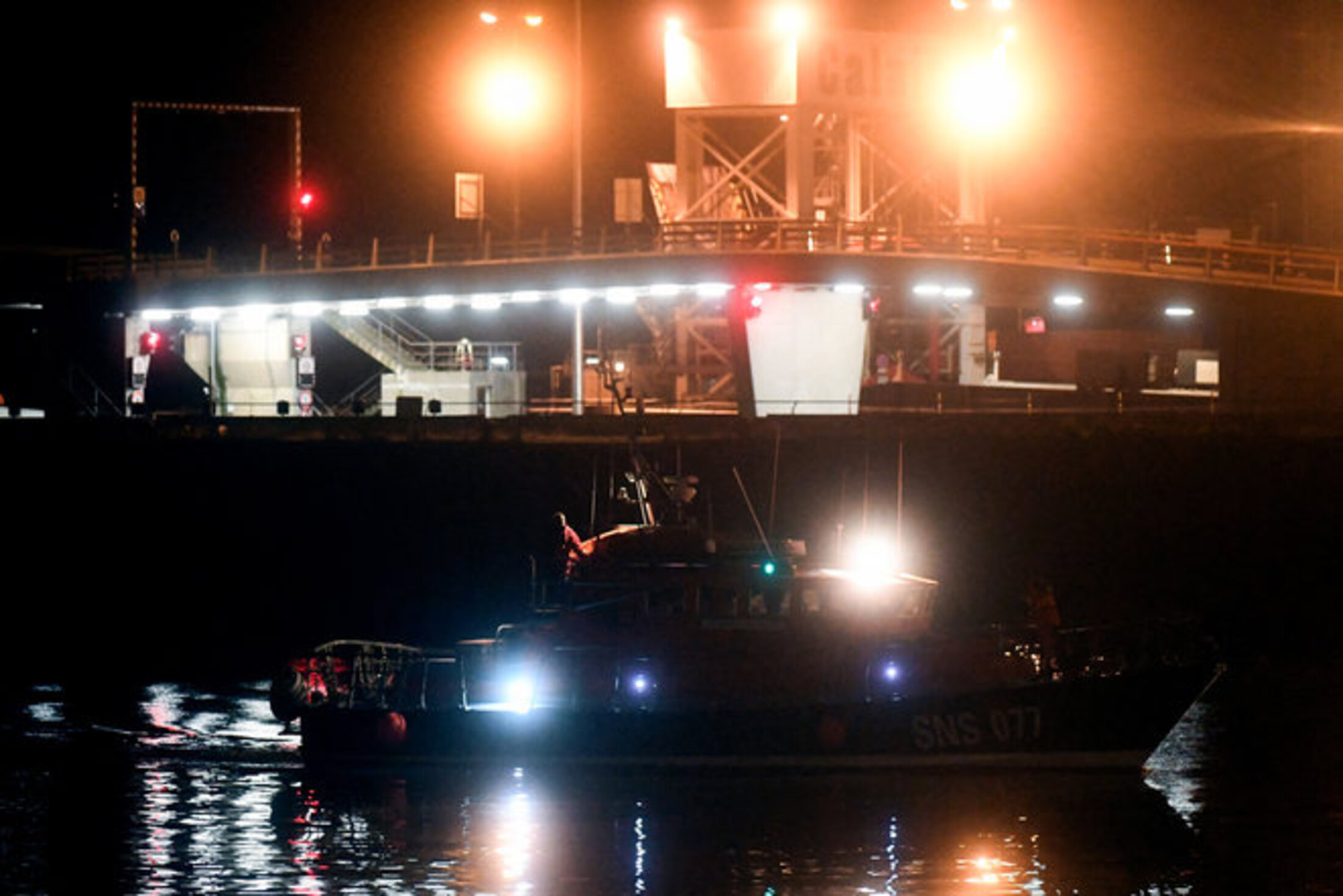

Enlargement : Illustration 1

“Our mission is to save lives, not to retrieve large numbers of dead people,” commented Bernard Barron, head of the Calais station of the French lifeboat services, the SNSM. He expressed concern at the possibility of more tragedies to come over the weeks ahead. While the weather has been relatively calm over recent weeks, prompting numerous attempts by migrants to cross the Channel to Britain’s shores, November is usually a month that heralds the return of treacherous conditions with storms that disrupt even the crossings of large ferries.

Four days before Wednesday’s tragedy, France's maritime prefecture for the Channel and the North Sea announced that, since the beginning of the year, an estimated 31,500 migrants had attempted the crossing to southern England from France, and that 7,800 migrants had been rescued at sea. The numbers taking to the sea from the coastline around Calais – which is the closest to British shores – has never been so great, and rescue operations for those in difficulty have become a regular occurrence.

According to the British Home Office (equivalent of an interior ministry), 886 people arrived in the country by clandestine crossings last Saturday alone. That brought the official total of such arrivals this year, up until the weekend, to more than 25,700 – more than three times the 8,469 recorded for 2020.

The crossings by dinghy have steadily increased following the progressive security clampdown over a period of two years of the port of Calais, and the Channel Tunnel terminal, which in the past were where many clandestine crossings were attempted by stowaways on trucks or trains. Lying scattered among the sand dunes of the beaches between the ports of Calais and nearby Dunkirk, empty fuel cans deflated dinghies are evidence of aborted crossings and those prevented by police patrols.

On Wednesday evening, French interior minister Gérald Darmanin arrived in Calais at around 8pm, where he spoke to the waiting press outside the town’s hospital. “I want to say here that those responsible for this horrible situation are the people smugglers,” he said.

Since the election of President Emmanuel Macron in 2017, the principal strategy to deal with the situation in and around Calais, where large squalid migrant camps become established, are dismantled and re-established soon after, has been a crackdown on people-smuggling networks. Since January 1st this year, more than 1,500 people suspected of either being smugglers or aiding and abetting smuggling activity, have been arrested.

Meanwhile, four suspected smugglers were arrested on Wednesday evening in northern France in connection with the tragedy that afternoon, announced Darmanin, although judicial officials on Thursday said no “objective” link between them and the ill-fated crossing had yet been established.

“It is a total misunderstanding of what’s going on,” said Juliette Delaplace, from the Calais branch of French humanitarian and social aid charity Secours catholique. “The last three people who disappeared had gone about things on their own, with canoes. Death is a fully integral part of our job at the border. You have to imagine what it’s like for people who continue to try to cross over when they know of the dangers because they have sometimes lost friends. That says enough in itself that they don’t have other options.”

At the quai Paul-Devot in the port of Calais, the quayside where the bodies of the dead were brought on Wednesday for initial forensic observation, a small crowd of several dozen had gathered in the evening in homage to the migrants. One woman carried a sign reading “How many dead do you need?”, which she turned towards two smirking police officers. The gathering was made up of volunteers and activists from associations providing aid to migrants, together with some local inhabitants, who placed candles on the paving stones of the dock. “Move away, vehicles are going to come past,” said a policeman, pushing along some of the group. Another kicked at the lighted candles. “Respect the dead,” someone shouted.

A few minutes later, a hearse came past, heading along the quayside, followed 15 minutes later by another, and yet another. Some of those who had come to pay homage began singing, borrowing the lines of a song by Breton group Katé-Mé about the plight of migrants living rough in France on their forced journey to a hoped-for better place: “I tell you. A curse on war, curse on the tanks, the guns, the fighting. I pass away on the rue des Lilas.”

Across the road, four young Somalian men, discovering what had happened, watched on in silence. “The sea, it’s too dangerous,” said one of them. “We don’t have money, so we cross using trucks.” Beside him, one of his compatriots said he had spent four years in Luxembourg, where he was enrolled in school until his right to asylum was withdrawn. With no legal status, he continued on his path. His pupil ID card still in his pocket.

None of the four would give their first name. They recounted the misery of their daily life in makeshift camps; how the police wake them up, the rough physical handling that goes with it, the expulsions from the camps, and how water and food supplies have become increasingly difficult to find since the authorities have prohibited aid associations from distributing such essentials to the camp sites. But also the permanent wandering around Calais, a town largely hostile to their presence.

“We don’t have money, but if we did have money we would leave on a boat straight away,” said the first. But meanwhile, they try their luck at hiding on UK-bound trucks. Day and night, they and others attempt to jump onto the moving vehicles entering the port, whose drivers accelerate when they see the would-be stowaways.

Like those who cross by sea, some succeed, and like those who take to dinghies, others don’t. On September 28th, Yasser Abdallah, a 20-year-old Sudanese migrant died from his injuries when he was struck by a truck he had tried to grab onto. One of his friends, Mohammed, turned up at the quai Paul-Devot on Wednesday evening. Visibly still affected by the loss of his companion, he looked on in silence.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse