In a report revealed on Monday, the United Nations has accused the military in Myanmar, the former Burma, of practicing genocide against the mostly Muslim Rohingya people in the country’s Rakhine state, and which has led to more than 700,000 of them to seek refuge from the violence in neighbouring Bangladesh.

The damning report, by the UN Independent International Fact-Finding mission on Myanmar and which is to be presented with added detail for a September meeting of the UN Human Rights Council, also accuses the Myanmar military of crimes against humanity concerning its treatment of minorities in other parts of Myanmar. It recommends that the evidence it has collected should be submitted to the International Criminal Court and names six leading military figures who it found should stand trial.

It is also critical of Myanmar's de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi, whose lengthy and arduous campaign for democracy in the country during its rule by the military saw her win the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize, for not intervening to stop the massacres.

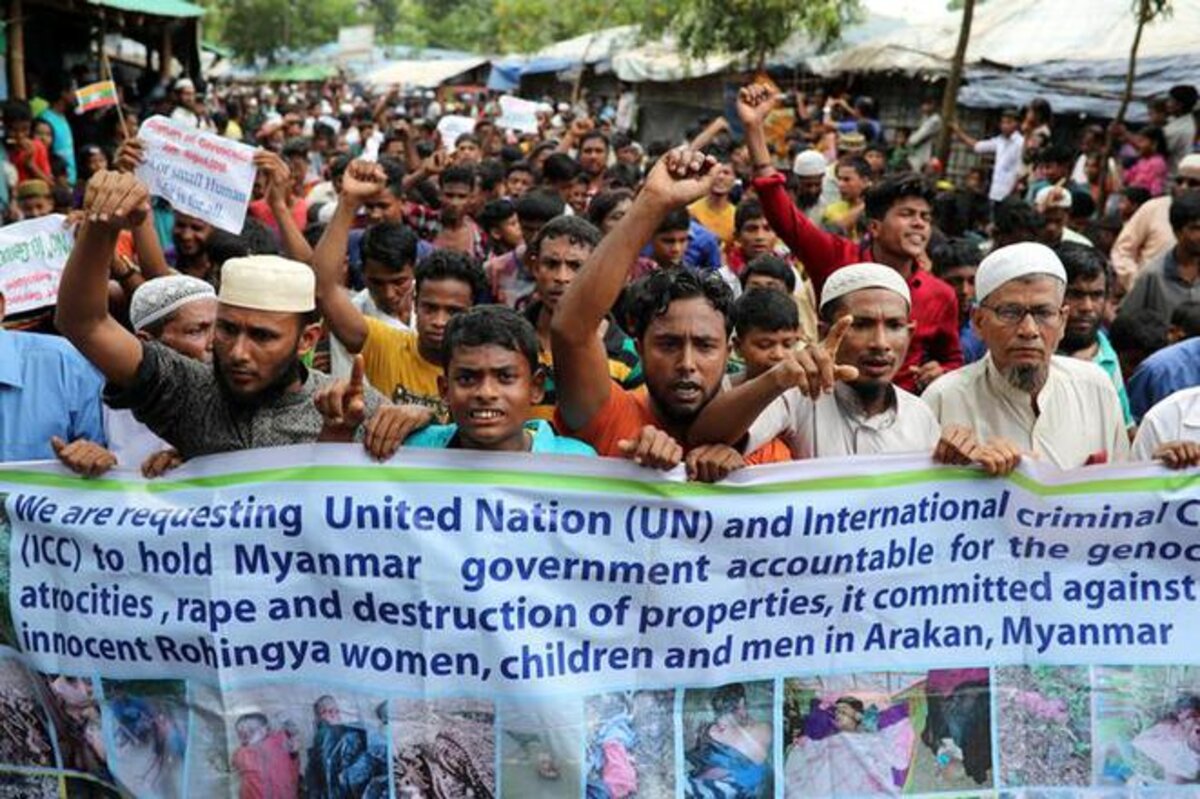

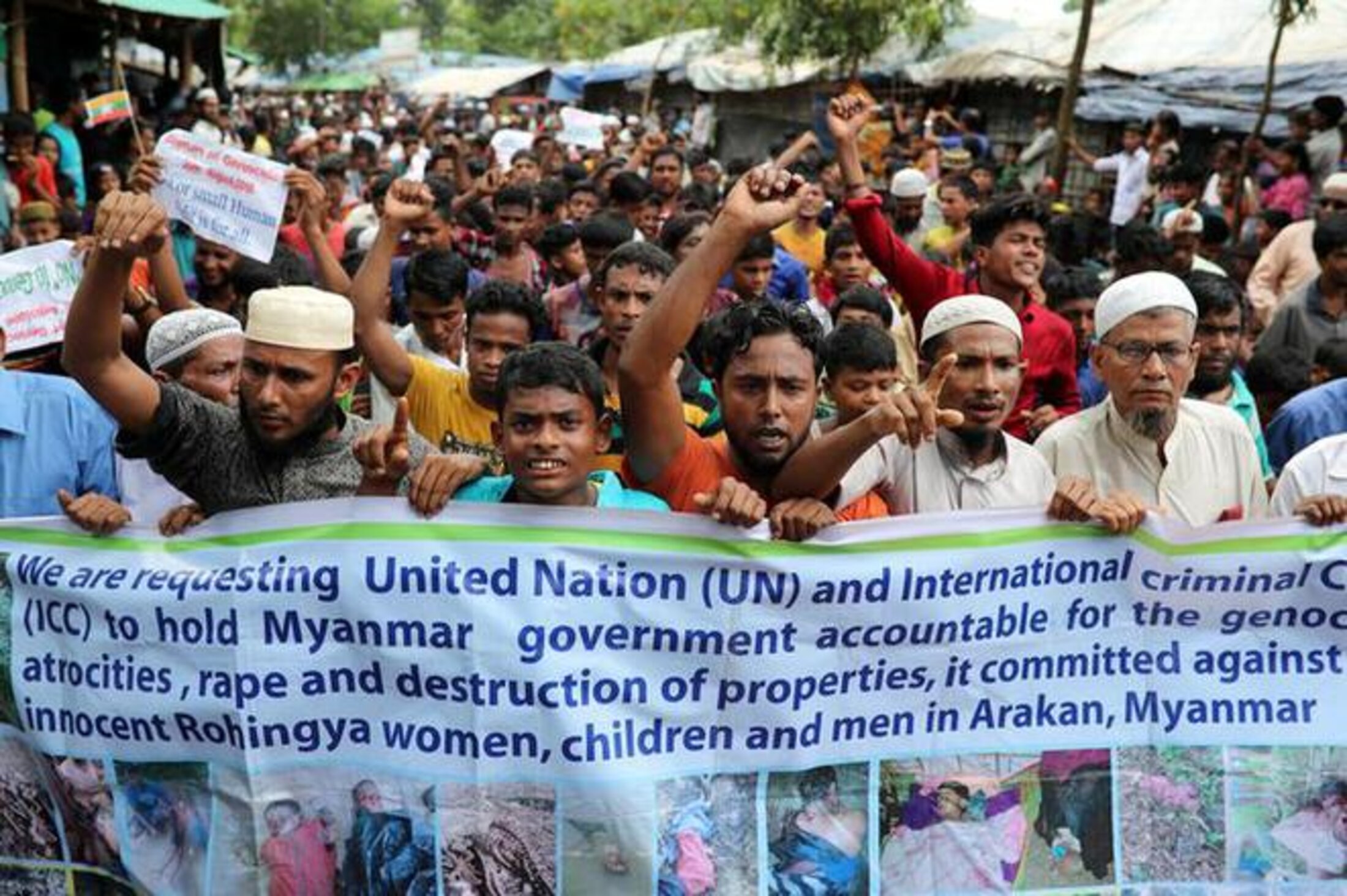

The publication of the report came just two days after tens of thousands of Rohinga in refugee camps in Bangladesh marked the first anniversary of the bloody military and militia campaign against them in Rakhine state with angry demonstrations demanding that the UN hold the Myanmar government, led by former pro-democracy dissident and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, to account.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

“Rape and sexual violence have been a particularly egregious and recurrent feature of the targeting of the civilian population in Rakhine, Kachin and Shan States since 2011,” said the report. It insisted no military necessity justified the operations of the Myanmar military, called the Tatmadaw, which involved “killing indiscriminately, gang raping women, assaulting children, and burning entire villages”.

“The gross human rights violations and abuses committed in Kachin, Rakhine and Shan States are shocking for their horrifying nature and ubiquity,” the report said. “Many of these violations undoubtedly amount to the gravest crimes under international law. They are also shocking because they stem from deep fractures in society and structural problems that have been apparent and unaddressed for decades.”

Those “deep fractures” include the longstanding ostracism of Muslims in a country where Buddhists make up close to 90% of the population, and which, besides the horrific operations against the Rohinga, has resulted in segregation and outright persecution.

Than Toe Aung was returning home to his parents’ house in Yangon (formerly Rangoon), Myanmar’s largest city, on January 18th 2018 when he was abducted by plainclothes police. “I thought my life was over,” said the 25-year-old, speaking fast and hardly pausing for breath [see footnote 1, page 3].

The political sciences student, who also works as a translator of Burmese into English, said it was about 11pm that night when a white van pulled up in front of him in the street and six men jumped out, one of them telling him not to move. In a state of panic, the young man ran into the foyer of a nearby hotel, but his escape was brief. He was given no help, and the men took hold of him, carting him off by his arms and legs. Hotel staff later provided him with mobile phone video of the abduction.

He said one of the group introduced himself as a policeman and handcuffed him, when he was placed at the back of a vehicle, kicked and gripped in a headlock, and called a “kalar” – a local racist term for people with dark skins. He said he was taken to a police station, where he was again assaulted.

According to his account, his father called his mobile phone and negotiated with a police officer for his release, after three hours at the station, in exchange for a cash bribe equivalent to around 130 euros. Since the incident, Aung lives a cautious existence, and never steps outside the family home after 9pm.

“These guys attacked me because of my physical appearance, because I am a young Muslim,” he said. “Maybe they wanted to let off steam or make a false arrest, I don’t know. Muslims are a minority here. The police and the judges are all Buddhists. When I was a child my father told me ‘Avoid fights and the courts because you will always lose’.”

But Aung filed a complaint days after the assault and decided to go public at a press conference at the end of January, when he also posted an account of the events and photos of his injuries on his Facebook page. He has since also lodged a formal complaint before Myanmar’s national human rights commission. His Facebook post has attracted thousands of visits, and while he has received messages of sympathy there have also been insulting anti-Muslim comments.

Than Toe Aung’s story is one example of the discrimination Muslims are subjected to in Myanmar, where about 88% of the population is Buddhist (according to a 2014 census) and about 4.3% are Muslim (Christians make up just more than 6%). The principal victims of discrimination are the Rohingya, a predominantly Sunni Muslim people from the state of Rakhine in the west of the country, who are denied citizenship under Myanmar law and who for years have been the object of a campaign of ethnic cleansing.

Subjected to a series of military-led persecutions since 2012, these culminated in the most violent campaign yet in August 2017 with the launch of a counter-insurgency operation, which also involved police and local militias, in response to attacks that month on police posts and also Hindu villagers by an armed Rohingya group called the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (Arakan is the former name of what is now the state of Rakhine). The military campaign, which began on August 25th last year, led to the deaths of 6,700 Rohingya including hundreds of children in the first month alone, according to a report by NGO Médecins sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) and the flight of what the UN estimates to be 725,000 Rohinga across the border into Bangladesh. One year later, the massacres remain unpunished and Muslims in Myanmar live in fear that the violence will spread further. Rohingya or not, they are only too aware that they are considered by many as undesirable, second-class citizens.

Among the most illustriate evidence of that is the fact that some Buddhist villages practice a ban on Muslims. In the region of the Irrawaddy Delta, in southern Myanmar, the hamlet of West Phar Gyi lies beside a largely muddy branch of the Irrawaddy which separates it from the outside world. “You are entering a peaceful village inhabited only by Buddhists” reads one of the signs set up on the banks. Another, weather-worn banner announces “Zone prohibited to Islam”. Here, Muslims are banned from renting a house, buying land or trading with local inhabitants.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The segregation is organised, with the support of the population, by Thon Tara, a Buddhist monk who is a member of the nationalist, anti-Muslim 969 Movement. “These notice boards are a rampart,” said Tara [1], dressed in saffron-yellow robes. “We don’t want kalars. They’re not from here, they come from abroad, from the Arab world.” Like many people in Myanmar, he follows the news using Facebook. His smartphone was hooked up to a charger, and as soon as it received a call an assistant would urgently bring it to him. Asked about the persecution of Rohingya, he said: “Since always, there are hosts and guests in the state of Rakhine. When the guests offend you, you have the right to send them away.” The London-based NGO Burma Human Rights Network has identified 23 villages across Myanmar which declare themselves, like West Phar Gyi, as ‘no-go’ zones for Muslims.

Many in Myanmar call the Rohingya people 'Bengalis'

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Many in Myanmar associate the presence of Muslims in their country with the period when it was a British colony, from 1824 to 1948, although in fact Muslims already lived in the region before. As the British began to expand their empire east (they gained total control of what was then Burma only in 1885), they encouraged Hindus and Muslims from India to settle in the country, some of them as civil servants in the local colonial administration, some as soldiers and others as builders and traders. It was a process that saw Buddhists marginalised to the lower ranks of society. The strong resentment by the indigenous Burmese population led to a violent reaction against both the Indians and the British, and riots which erupted in the 1930 in what was then Rangoon (now Yangon), mostly involving clashes between Burmese and Indians, left more than 100 people dead and an estimated 1,000 injured.

In 1962, a period almost 50 years of military rule began when General Ne Win, who had served briefly as prime minister, led an army coup against the civilian government. The new dictator expelled Muslims from the ranks of the army and administration and championed Buddhism as a means of gaining public popularity. Military rule ended in 2011, when a series of reforms allowed the return of a civilian government. After a long period being virtually cut off from the world, the population suddenly discovered the internet, media freedom and economic liberalisation, with the opening-up also of foreign investment. But the transition also led to a period of instability, and with it a backlash against minority groups of society which was fanned by nationalist Buddhist monks who became artful in the use of social media.

In 2012, deadly clashes erupted between Buddhists and Muslims in riots in Rakhine and which spread elsewhere in the country. In October 2016, and again in August 2017, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, which had formed in 2013 after the earlier riots, claimed responsibility for attacks against police and border posts which left a number of officers dead. That prompted a brutal campaign of “clearance operations”, tantamount to ethnic cleansing, by the military, aided by Buddhist militias, to push the Muslim population out of west Myanmar.

As the mass exodus of Rohingya across the border into Bangladesh began, Aung San Suu Kyi, the former pro-democracy movement heroine and Nobel Peace prize winner, who since 2016 has been Myanamar’s State Councillor – a position equivalent to prime minister – said reporting of the crisis had been exaggerated. In a statement issued by her office on September 6th 2017, the de facto leader of the country said what she described as fake photos were "simply the tip of a huge iceberg of misinformation calculated to create a lot of problems between different communities and with the aim of promoting the interest of the terrorists".

While Aung San Suu Kyi was strongly criticised by much of the international community for her failure to halt the massacres committed against the Rohingya, her supporters underline the limits on her powers; under the constitution, the military occupies 25% of seats in Myanmar’s parliament, giving it a right of veto on government decisions, and it controls the ministries of interior and defence and frontiers. Aye Lwin, the Muslim founder of the Myanmar branch of Religions for Peace, a multi-faith organisation for the promotion of dialogue between religions, is one of those who defend Aung San Suu Kyi’s role. Lwin, chief convener for the Islamic Centre of Myanmar, sits on the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, a body founded by the Aung San Suu Kyi in September 2016 and which was presided over by the late Kofi Annan, the former UN secretary general. It was given the brief of finding solutions to bring peace to the state, but the extent of the violence that began in August 2017 has sidelined its work. Lwin said of Aung San Suu Kyi: “Everyone couldn’t care about Rakhine and yet she created this commission, braving the opposition of the military, of the USDP [editor’s note: a political party rooted in the former military junta], Rakhine Buddhists. An incredible number of obstacles.” [1]

The creation of the commission is the only significant action that Aung San Suu Kyi has taken to ease the situation of the Rakhine Muslim population, and she has shown no particular compassion over the crimes committed against the Rohingya – whose name she for years avoided pronouncing. Many in Myanmar call the Rohingya people “Bengalis”, a term which designates them as Bangladeshi illegal immigrants. She has distanced herself from the Muslims within her National League for Democracy party, after calling on them not to stand as candidates in the 2015 general elections in order to maximise the party chances at the polls, a supposedly temporary move that has never been rescinded.

Yangon, a city where hatred can quickly boil over

Aung San Suu Kyi’s government sits above a secretive and xenophobic administration inherited from the military dictatorship. The motto of the immigration and population ministry is “The Earth will not swallow a race to extinction, but another [race] will”. Religion and ethnic origin – something that is confused with race in Myanmar – are inscribed on identity cards. When Muslims receive or renew ID papers, they are described as being of “mixed blood” and must indicate their filiation with a foreign country. “It is a racist procedure that exists since decades,” said Aye Lwin. His own ID card presents his ethnic origins as Bamar, Mon and Afghan – although he has never set foot in Afghanistan where a distant relative lived.

The discrimination is not set in law but is perpetuated by the civil servants of the administration. If those seeking ID papers raise an objection they run the risk of not receiving them for months or even years, as was the case for Nickey Diamond, a human rights activist in Myanmar with the Fortify Rights organisation, who waited seven years for his own. Effectively, he says, a person can become stateless, unable to vote, open a bank account or register with an educational establishment.

Khin Maung Cho is a lawyer based in Yangon, specialising in questions of citizenship. Within his windowless office lined with bookshelves, he guides numerous Muslims through the administrative maze. He says the Rohingya crisis has aggravated their difficulties, and that the administration currently forces many Muslims to register themselves as "Bengalis", even though they may have no links with Bangladesh. If they refuse, he says, they will lose their ID card and citizenship.

There is little public support for the Muslims from the Buddhist population, but an exception is Myat Kyaw. This 37-year-old fervent practicing Buddhist lives in a bamboo-built house in a poor district of north-east Yangon, and works as a taxi driver at nights. By day, he leads a campaign challenging the nationalist Buddhists, using Facebook as his vehicle to organise petitions and meetings. His Facebook account has been hacked several times and he has received messages proffering death threats (see this report by news agency Reuters on the hate campaigns against Rohingya and other Myanmar Muslims).

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Myat Kyaw believes he represents the true spirit of Buddhism, and when in October 2017 Muslim traders were chased away from an area near the Bhuddist Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon, the most sacred in Myanmar, by a crowd led by Buddhist monks, he joined with others in lodging a formal complaint with police, who he said did nothing. “I don’t know if I can change things, but I try,” he said [1].

Myo Min (not his real name, which is withheld on his request) is a 25-year-old Muslim, who keeps his Rohingya origin secret from all but his close entourage. He left Rakhine in 2012, subsequently living in Bangladesh, Malaysia and Thailand. He secretly returned to Myanmar in 2016, living among the Muslim community in Yangon. “I never say I am a Rohingya,” he says [1], keeping his voice down at an isolated restaurant table. “In public, I don’t speak my mother tongue, and I only use Muslim taxis, for safety.” He is only too aware that the city has ears, and that hatred quickly boils over. In May 2017, nationalist monks laid siege to an apartment building where Rohingya were suspected of living, and only the intervention of the police prevented the likelihood of a lynching.

Myo Min’s mother and brother still live in Rakhine state, despite the massacres perpetrated since August 2017. Isolated far away from them, his life is one that is haunted by fear, and he says that he is certain that if he does die, nobody would be made aware of it.

-------------------------

1: The citations marked 1 were originally translated into French, and subsequently into English.

-------------------------

- The French version of this report can be found here.