These times of democratic crisis offer a new lease of life to old promises. Notably those contained in the programme of the national council of the French Resistance movement (CNR), established in March 1944. Under a chapter entitled ‘The establishment of the largest democracy’, it demanded not only the guarantee of freedom of the press but also the respect of “its honour”, namely its “independence regarding the State [and] the power of capital”.

The challenge for Mediapart when it was created four years ago, on March 16th 2008, was to put into practice those ideals and to prove their continued relevance today. We met that challenge, but there remains the task of keeping them solidly alive over the long term.

In its allusion to the honour of the press, the CNR was addressing journalists themselves, in something resembling a moral command. It was a way of telling them that they are the holders, guardians and servitors of fundamental democratic principles, namely the right to know, the pluralism of information sources, the quest for truth and the respect of the public.

In other words, it was above all down to them to defend these principles upon pain of dishonour to their job and profession. For if they stand back and watch on passively while any of these values are degraded, they can hardly be surprised at their own discredit.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

From the very first days of the liberation of occupied Paris, in August 1944, French writer Albert Camus, in his editorials for the daily paper produced by the Resistance, Combat, became the spokesman of these principles. Writing in terms that would today no doubt provoke mocking criticism, that we are all too familiar with, he warned: “Everything that degrades culture shortens the paths that lead to servitude. A society that accepts to be distracted by a dishonoured press […] heads towards slavery, despite the protests of those same people who contribute towards its degradation […] It is however our task to refuse this rotten complicity. Our honour depends on the energy with which we will refuse compromise.”

Mediapart wanted to demonstrate that this rediscovered honour is, far from being a defeated ideal, what remains for the media as the only way forward to provide a professional recovery and an economic renaissance of our jobs and industry. Journalism has no other vocation than that of a service for the public, a public who have the right to know everything that is done in their name in order to be an acting part of the democratic process, free in their choices, independent in their decision making. With the digital revolution, we wanted to prove that by following these demanding principles, we could create an innovating press, both independent and profitable. Profitable because it is independent.

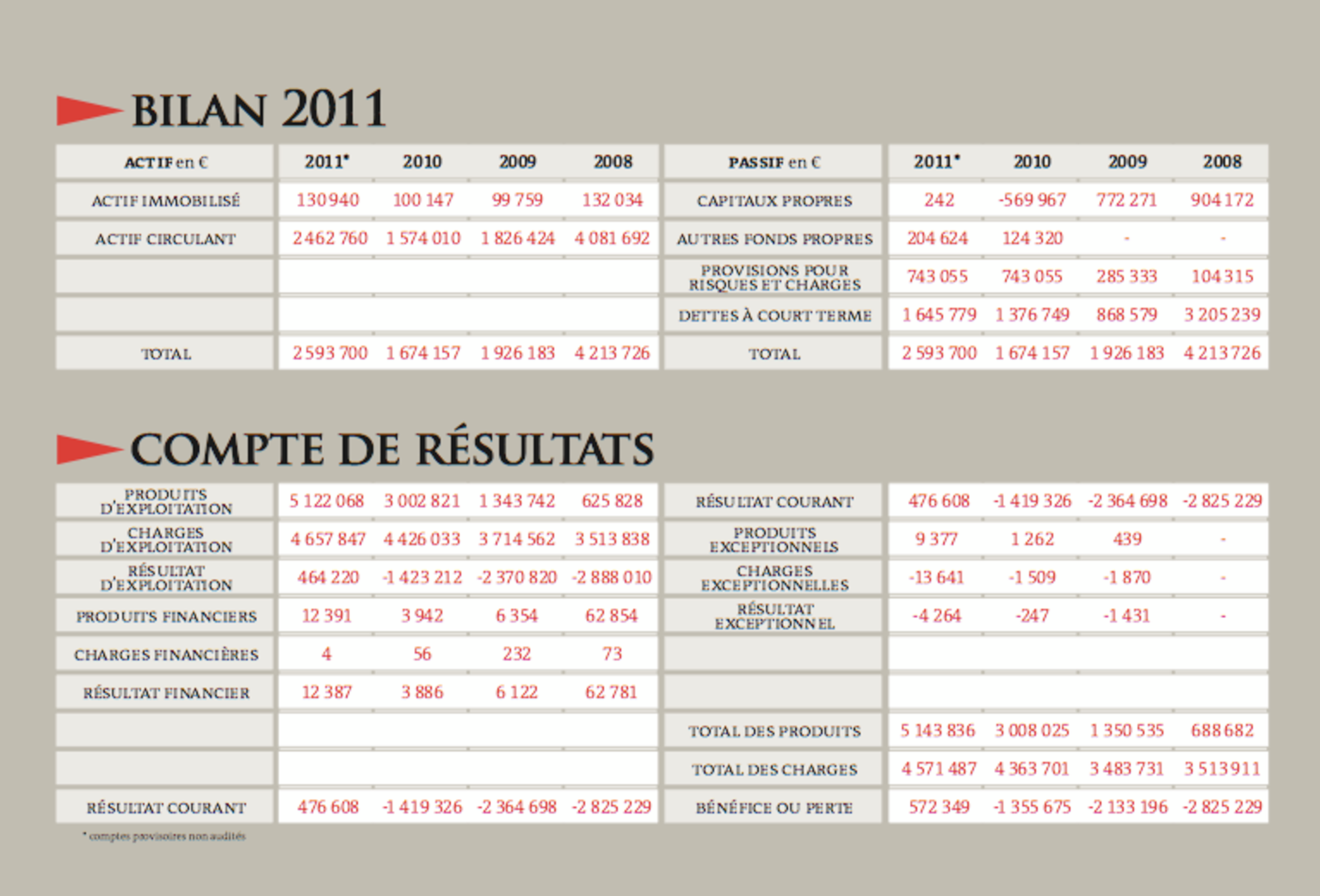

Mediapart's accounts

As every year at this period, Mediapart makes its accounts public. The press file detailing our four years as a media exception can be downloaded here. Mediapart lives from just one source of income; that of the loyalty of its subscribers, who by the end of 2011 numbered 58,500 and who today total 62,000. With a turnover of 5.1 million euros, and with no debt burden, Mediapart made a net profit in 2011 of 572,349 euros. Mediapart’s growth, regular and consistent, has seen its audience rise to more than one million unique users per month.

Below is a graph showing the evolution of turnover, followed by a text (in French) explaining the aids and subsidies received by Mediapart during 2009 and 2010 and which we have decided, after moving into profit, to no longer receive.

Below is a detail of our balance sheet and earnings statement for 2011 (available in French only). Mediapart and the investigative weekly Le Canard enchaîné are the only broad news publications in France which reveal their yearly accounts.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Keeping to an independent path

Independence, investigation and confidence are key words behind Mediapart’s success. The independence of a journal that has no strings attached to financial or political powers; investigation lies at the heart of our editorial culture, one that brings instructive news through revelation; confidence from our readers in our unique project through its participative channels, whereby readers can debate and criticise and contribute their expertise amid the plurality of opinions published. These triple values behind our success must now be made solid and durable.

This requires placing Mediapart permanently sheltered from both the economic crisis and appetites created by our success.

To reach the first objective, Mediapart must continue its growth, with your help, in order to establish itself as a new medium of reference and quality amid this digital revolution. Our development aims for 2012 are essentially concerned with consolidating the loyalty of our subscribers, notably by inciting them to opt for automatic bank payment transfer to avoid the problems of payment encountered with credit card debits.

As for the second objective, this is now at the centre of discussion among the Medipart board. The independence of Mediapart is written in stone by the composition of the board, with the preponderant position of its four co-founders, all of whom are employees of the company. Our shareholders have not changed since our last increase in capital during the summer of 2009, with the majority of shares controlled by Mediapart’s founders and the association of small investors who make up the ‘Amis de Mediapart’, as shown below.

The current pact between Mediapart’s various shareholders runs until the spring of 2014, when investor partners are given the opportunity of leaving the project. That leaves us two more years to find a solution that remains loyal to our initial engagement, that of making Mediapart a press organization that is controlled by those who work in it. The task is difficult, and already urgent, requiring the resolution of various sensitive questions, including legal, financial and managerial ones, and that of timing.

While we still seek a solution, which we hope will be as innovating as it is effective, we already know the issue we face. It is that presented by Albert Camus, in 1944: “Any moral reform of the press would be in vain if it were not accompanied by political measures intended to guarantee for newspapers a real independence with regard to capital.” It was also that which, in the spring of 1968, was posed by Jean Schwœbel, the first president of the first committee of editorial staff shareholders in France, that of the daily Le Monde, in his book La Presse, le Pouvoir et l’Argent (‘The press, power and Money’). The book (pictured above right), which set out a programme that is still relevant today, defended an independent press as being “a service of public interest that is not under the supervision of public powers” and argued for press organizations “with limited lucrative value” in which journalists were part-shareholders.

A challenge for the profession and society at large

If Mediapart is clearly an exception in a largely decayed media landscape, it would be welcome that it serves as a model. The pleasant comments that we often receive about the courage of our reporting suggests that journalists cannot do their job with dignity unless they are courageous, taking risks and exposing themselves to danger. That’s a curious notion, even if at Mediapart we are proud of our energy as lone chargers. For does one ask little fish swimming in a polluted sea and in face of sharks to be courageous? Should not the de-pollution of the sea be the urgent priority?

Enlargement : Illustration 7

If citizens don’t concern themselves with the conditions by which their own right to a free press are determined, a press that is honest and plural, they should not be surprised by the disastrous result - and which they deplore. Otherwise put, in order that journalism can recover its health and that the institution of the press is re-built, the ecosystem in which it exists, and which conditions the one and the other, must change.

That is not only the job of journalists, but also that of public will to see an end to the scandal that tarnishes our supposed democracy and a media system that is governed by industrialists alien to our profession, corrupted by conflicts of interest, subservient to heightened pressure from executive power, dependent upon public subsidies that are opaque and unhealthy, driven by the race for audience figures via entertainment, increasingly turning its back on that ambitious objective set out by Albert Camus for a press that is concerned with “placing the public at the level of what they have best in themselves”.

Mediapart hopes that the new parliamentary majority that is returned after general elections due in June will provide a legislative framework for this new and virtuous media environment. We call for a new and fundamental law, on a level of that which in 1881 established the freedom of the press in France and in a context similar to that of today, one of necessary democratic re-foundation and decisive industrial revolution.

Through its success, Mediapart has demonstrated that the questions put before all of our profession are not the result of hare-brained ideas from idealists de-connected with reality. They are those that are concerned with helping the creation of sound and durable values, proving that journalism can, on its own, ensure the economic survival of a media organization. The honour of journalism is the guarantee of its success. It is by not compromising in its mission, its values and principles, by vigorously defending its independence, by putting itself at the service of the public, and the public alone, that it can hope to create jobs and guarantee the solidity of the business.

In his preface to Jean Schwœbel’s 1968 book, cited on the previous page, the philosopher Paul Ricœur called for just such a political intervention to protect the gathering of news and information from the influence of money and power. He underlined the challenge to democracy from the “competent oligarchies” who were “associated with the powers of money”.

“Everywhere, the same confiscation is found,” he wrote. “And everything sends us sliding towards it: the growing complexity of problems in advanced industrial societies, the laziness of citizens, their appetite for well-being without troubled thoughts […] the interests of feudalisms. De-politicalisation is, at heart, nothing other than this resignation of most, reciprocal to the confiscation by the few of decision-making. It is here that information is the necessary condition of democratization: for what is democracy, if not the regime which ensures for the largest possible number – if not for everyone – the participation in decision-making at every level?”

While briefly providing relief against this somber picture, the happy energy of the events that same year in May 1968 were insufficient to erect a lasting barrier against this spectre of confiscation. Quite the opposite, in fact, the spectre wants revenge, prowling about with ever more intent. It is for us, all of us, to ward it off and to send it packing, there where we are required to, in our professions and our companies, and with the power and means born from a radical determination to recover democracy.

- Edwy Plenel is Editor-in-Chief, and a co-founder, of Mediapart, and was formerly editor of French daily Le Monde.

-------------------------

English version: Graham Tearse