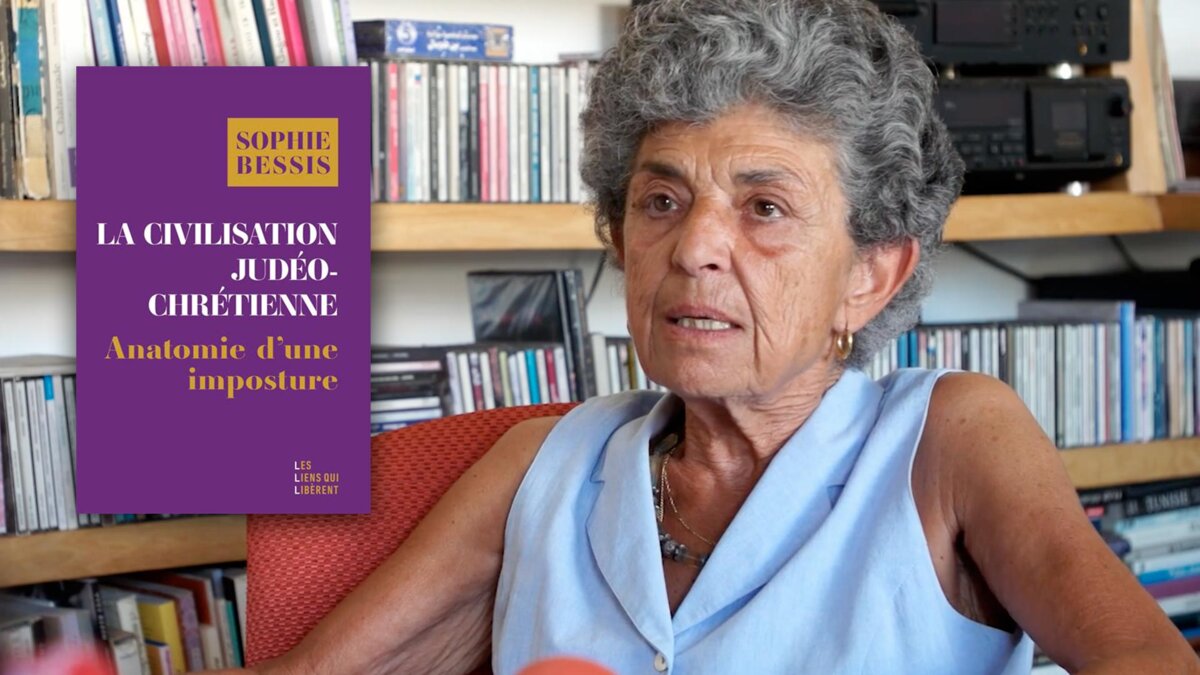

The phrase has become a part of everyday language, but for French historian Sophie Bessis, the notion of “Judeo-Christian civilisation” is basically a deception, an argument she sets out in lively manner in a book published this month in France, La civilisation judéo-chrétienne*.

Bessis, born into a leftwing Jewish family in Tunisia in 1947, is a prolific and prize-winning author, some of whose books have also been published in English, notably her 2003 work Western Supremacy: The Triumph of an Idea? (Bloomsbury). Formerly a teacher with the Sorbonne university in Paris, and research director with France’s Institute for International and Strategic Affairs (IRIS), she served as deputy secretary general of the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), was editor of Jeune Afrique magazine, and worked as a consultant for United Nations organisations UNICEF and UNESCO.

Her 124-page essay makes for rapid reading in parts, and is above all convincing. Observing that the concept of “Judeo-Christian” society is almost non-existent outside of Western countries, including in those parts of the world where the Christianity is widespread, such as in South America, Bessis writes that “this extraordinary semantic and ideological invention, one of the most-used of our time, can be placed in the category of ‘alternative truths’”.

In her analysis of what she regards as the fraudulent character of the phrase, Besse begins by charting its history, which is revealed as relatively recent – up until the advent of the 1980s, Europe was more often described as “Greco-Latin”. What that filiation shares with the “Judeo-Christian” notion is the exclusion of the East from European heritage, founded on a supposed civilisational monopoly.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

An essential stage in this process is that of accepting that Jews, who for long were regarded as Levantines, have become European, even if, Bessis writes, that did not yet imply “that Judaism and/or Jewishness be set up as central constituents of European – and more widely, Western – civilisation”.

The historian argues that in order to adjoin Judaism to the “Christian origins of Europe”, the tardy recognition of the specificity of genocidal acts towards Jews was necessary, “and consequentially the beginning of the expression of a guilt or, at the very least, a collective responsibility, on the part of Europeans”. Whereas in fact, in the immediate post-Second World War period, the inmates of German concentration camps were largely referred to as “deportees”, without identifying the categories of those who were sent to them.

A manner for the West 'to wash itself of its crimes'

After the Second World War, Europe, seeking to restore a supposedly superior civilisation that had been stripped bare by the Nazi death machine, set about two different strategies, argues Bessis. The first of these was not only to hasten the creation of the state of Israel, but also to “almost unconditionally support” its expansionist policy.

She writes: “So that the West could re-establish this moral superiority which it had made into an exclusive privilege, but which was more than shaken by Nazism, it was necessary, and still is, for Israel to be not only the heir of the victim, but also itself a victim for eternity. It had to be definitively innocent and that never, whatever its actions, could it be lumped with the camp of the executioners. It was on this condition that the West believed it could wash itself of its crimes.”

The second strategy consisted of popularising the phrase “Judeo-Christian” to transform it into “the plinth of Western civilisation”, which was however a delicate endeavour.

The long history of violence towards Jews in Christian lands had to be blanked out, and for that it was necessary to exclude Islam from the Abrahamic revelation, to supposedly constitute a whole but from which one of the three monotheistic religions was expelled. That is despite the fact that, Bessis writes, “far from being a new religion that has no link with those that preceded it, Islam is situated in an obvious continuity with the spiritual currents of the period of its birth, rooted in a common culture implying profound affinities with diverse currents of Christianity and Judaism”.

It is an operation that required a misrepresentation of history. Besse gives a striking example of this with The Song of Roland, a medieval French epic poem about the 8th-century Battle of Roncevaux Pass in south-west France when, “for the requirements of Christianity, the [attacking] Basques were opportunely transformed into Saracens, fought by the intrepid hero in the foothills of the Pyrenees”.

The construction, from beginning to end, of an alliance supposedly profound and ancient between Christianity and Judaism was strengthened by the development in the Middle East of the theory of a “Judeo-Christian conspiracy”, notably concerning the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, perceived as being a foreign body installed by force upon the land of Islam. The theory, writes Bessis, became “a central feature of anti-Western discourse in all of the region”.

Bessis argues that this is not only in reaction to the mirror held up by the West. The Arab-Muslim world has used it “to expel from itself its Jewish part”: “The designation of exclusively Western Judeo-Christian culture allowed for the burying beneath it of what is Judeo-Arab and Judeo-Muslim, and to censor the historical existence of oriental Judaism and to attempt to erase it from the traces of collective memory.” That path led to structural forms of “state anti-Semitism”, as happened in Algeria.

Bessis appears to believe it difficult to envisage an exit from the deceptive notion of Judeo-Christian civilisation. “[Being] too convenient for too many people for it to disappear, serving over several decades to hide, to possess and to exclude, it certainly still has a future,” she writes, while also arguing the necessity for its deconstruction, for otherwise it will “make the fractures of today incurable”.

* La civilisation judéo-chrétienne is published in France by Les Liens Qui Libèrent, priced 10 euros.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse