André Markowicz is one of France's best-known literary translators. Born in the Czech capital Prague to a Russian mother and a French father of Polish origin, arriving in France at the age of four, he became celebrated for his translations into French of the complete works of Russian author Fyodor Dostoyevsky, and won the coveted Molière French theatre prize for his translation, together with his wife Françoise Morvan, of Anton Chekhov's play Platonov. Markowicz has just published an extraordinary anthology of Russian Romantic poetry embedded in the tragic fate of the circle surrounding the man considered by many as Russia's greatest author Alexander Pushkin. Dominique Conil interviews him here about his approach to translation ("What counts isn't the language you're translating from, it's the one you're translating into," he says) and the story of a generation crushed by tsarist repression after a failed revolt to overthrow Nicolas I.

-------------------------

His name tops the bill on the cover of the book, and rightly so. André Markowicz's avowed aim in his latest work, Le Soleil d'Alexandre: Le cercle de Pouchkine 1802 - 1841 ('The sun of Alexander - Pushkin's circle 1802 - 1841') is, as he puts it modestly, to "put a little Russian culture across in French".

Where we meet, the hellish din of the elevated stretch of the Paris metro and all the blaring traffic underneath doesn't seem to bother him in the least. On his table at the café terrace are his open notebook, his thin black pencils and a book...in Chinese, as it turns out. This is, shall we say, his latest challenge - after having translated Chekhov, Dostoevsky's complete works, Pushkin and, to name just one foray beyond the Russian pale, Shakespeare.

But he can't read or speak Chinese. What interests him, he explains with zest, is that the ideogram "doesn't represent a word, but a concept." Which is why he's meticulously comparing various Russian and English translations of the Tang Dynasty poet Lu Zhaolin. But he'll get back to his ideograms later on.

This man is something of a Rosetta Stone. "What counts isn't the language you're translating from, it's the one you're translating into." Vasily Zhukovsky, the father of Russian Romanticism, Pushkin's mentor and a prominent figure in Le Soleil d'Alexandre, would have concurred wholeheartedly. Without knowing Greek, he did an apparently unrivalled translation of the Odyssey based on German translations - and his own word-by-word scrutiny of the original. What André Markowicz and the Pushkin circle (1802-1841) share is an unbridled curiosity: like Zhukovsky, Markowicz will plunge headlong into any literary period whatever.

Like many literate Russians of the 19th and early 20th century, Markowicz didn't learn languages, he grew up with them. At home he spoke French to his father (the family, communist by tradition, had quit Poland two generations back) and Russian to his mother, who had made it out of the Soviet Union thanks to her marriage. He seldom goes to Russia: "I love Russian culture, I love the people, but Russia not so much, I guess. I prefer travelling in my head. My, albeit thwarted, dream is never to leave home at all!"

Turning the tables on the latter-day Russian backlash against "Western influence", Markowicz has travelled long and hard into the very sound of Pushkin's poetry. "His poems hinge on sound. If you you're not translating the sound, you're not translating anything."

Alexander Pushkin was the fountainhead of Russian modern literature. Gogol, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Chekhov, later Blok, Akhmatova, Mayakovsky, Bulgakov, Tsvetaeva, even Solzhenitsyn and Sinyavski, they all read him, wrote about him, drew inspiration from him. The very title of Markowicz's book, Le Soleil d'Alexandre, comes from an Osip Mandelstam poem about "the sun of Alexander", for Pushkin came to be known as "the sun of Russian poetry".

The Decembrists

Basking in that sunshine was a group of brilliant young poets, most of them Pushkin's close friends, whose literature and very lives were inextricably bound up with his. These were the fathers of Russian Romanticism. "They were totally into Europe. Their literary influences, their sources, were Byron and Goethe. The influence of French literature was meagre. Hugo was deemed a minor author at the time, criticized for drawing a distinction between the sublime and the grotesque in his Preface to Cromwell, the French Romantics were considered very long-winded."

Russian Romantics aimed at a leaner style, hence the modernity of a number of their works. Besides, in the 1830s, a number of the French Romantics were conservatives. And politics mattered to the bold 'Decembrists' who, after their abortive attempt to overthrow the tsar, were to suffer unrelenting persecution for their political convictions.

Romanticism was the artistic upshot of those convictions, of the dreams and sufferings of the Decembrists and their immediate successors. "That's crucial. It was the beginning of a moral code, of ethics." In fact, although the word itself was first coined in Russia in the 1860s, they were the intelligentsia of the age.

These young people, mostly well-bred (Pushkin himself was born into the Russian nobility), conversing with ease in Russian, French and German, had everything going for them. And they were bound to one another by indissoluble ties of friendship and intellectual affinity. The influence of French literature may have been meagre, but that of French Republican ideals was huge.

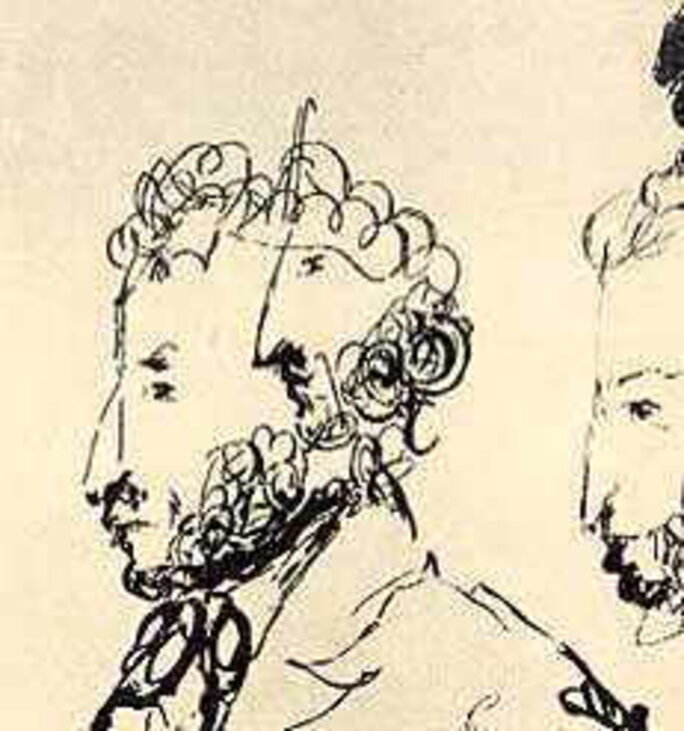

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Inspired by 18th-century social critic Radishchev , who had been persecuted and exiled to Siberia under Catherine the Great, and raised on Revolution, they aspired to a more just society - though their demands paled beside those of the Russian nihilists, terrorists, socialists and anarchists who were to follow. They wanted a constitutional monarchy, equality before the law, and the abolition of serfdom (which did not come to pass till 1861), even if it meant twisting the tsar's arm. They attempted a coup d'état on December 14 1825, the day Nicholas I was to take the throne after the death of his older and enlightened brother, Alexander I, emperor from 1801-1825. And they failed. "I think Nicholas I got the fright of his life that day," remarks Markowicz, a fright for which the tsar would make them pay dearly.

Le poète est partout persécuté

Mais en Russie son destin est le pire

Ryléïev était né pour la beauté,

Mais le jeune homme aimait la liberté

La potence a brisé sa vie martyre.

The poet is persecuted everywhere

But in Russia his fate is worse

Ryleyev was born for beauty

But the young man loved liberty

The gallows crushed his martyred life.

These lines by Kuchelbecker , which Markowicz renders in rhyming French verse, were penned in 1845 in dismal Siberian exile, a year before he died blind from tuberculosis. As for Ryleyev, the leader of the Decembrist Uprising, he was sentenced to be drawn and quartered, but the tsar let him hang alongside the other four leading conspirators. "Accursed country," he said when the ropes holding three of them broke as they fell through the trap-door and had to be restrung, "where we don't know how to conspire, how to judge or how to hang."

History and home, worlds apart

Nicholas I meted out various punishments, but almost all led to an early death. His "friends of December 14th", as he dubbed them, were imprisoned for decades, packed off to Siberia, exiled to faraway backwaters, censured, or sent to what was even then the horrendous Chechen front: "scorched glens of the recalcitrant Caucasus," as Pushkin described the setting of the Caucasian War (1817-1864).

Griboyedov, the author of the brilliant verse comedy Woe from Wit, was punished by assignment to the most dangerous diplomatic post of all, Persia. When he refused to give up an Armenian eunuch and two Armenian girls who had escaped from the harems of the Shah and his son-in-law, an angry mob stormed the embassy and massacred them all. Griboyedov's body, mauled by the mob for three days, could only be identified by a scar on his hand from a previous duel. The arc of his oeuvre reflects the passage from the concerns of his youth - love and passion, nature and the upheavals of the soul - to resistance and, ultimately, despair.

That despair is echoed in Odoevsky, a polymath who was known to contemporaries as the Russian Faust:

Moi, comment respirerais-je

Enterré vivant, sans voix ?

L'air est libre, mais pas moi

How would I breathe

Buried alive, voiceless?

The air is free, but not me.

Fellow Decembrist Gavriil Baten'kov, kept in solitary confinement at a fortress for 20 years, was brought to the brink of madness.

Le fer suinte ; on touche là

Des traces de souffrances mortes

Oozing shackles: there we touch

traces of dead sufferings

he writes in The Wild One, which was to become a cult poem among the revolutionaries and the inspiration for part of Dostoevsky's The Idiot.

As for Pushkin himself, he was, at least on the face of it, better off from the start. By the time he graduated from high school he was already hailed as a literary genius. He frequented and caroused with the radicals and, after years of exile in the provinces, then with the tsarist court. At one point, he went as far as to denounce his own seditious poems to the police. Of his internal exile to the family estate, he writes:

Et je m'en fus loin des divas

Des restaurants, des huîtres grasses,

Des loges sombres - juste cieux !

Et de certains puissants messieurs

Vers les forêts et vers les glaces

Les ombres de Trigorskoïe

Triste retour dans mes foyers.

And so I went far from the divas

of the restaurants, of the fat oysters,

Of the dark dress circle boxes - good heavens! -

And of certain powerful gentlemen,

To the woods and the ice

The shadows of Trigorskoye

Sad return to the family hearth.

When he was finally allowed back to Moscow, Nicholas I granted him his favour...by gradually destroying him. Pushkin was humiliatingly assigned to an honorary post normally reserved for youngsters, every line he wrote was personally censored by the tsar, and he was barred from travelling without permission. Russia's pre-eminent poet was reduced to a bird in a gilded cage.

The public subsequently found him a bit passé, though he was only in his 30s and writing some of his greatest works. The days of instant success were over. The sublime Lermontov took pride of place, along with others, while the Decembrists were counting their dead and publishing under pseudonyms, if at all. On the other hand, Pushkin also fell from grace in liberal circles when he wrote in favour of the tsar's brutal repression of the Polish uprising.

"This is a key element," explains André Markowicz, "which we then find throughout Russian culture, a total split between History, regarded as a fate that cannot be changed, neither good nor bad, and the home, life in the margins of history, the realm of freedom."

That split, which was to prove illusory, especially a century later in the purges, was in France often hastily ascribed to Russian resignation. But it was more a matter of partitions, witness the stark contrast between the refined, sensitive poetry of Tyutchev and his apologies for absolutism when he became head censor at the end of his career.

An enduring conversation

And yet, in spite of it all, reading Soleil d'Alexandre is more uplifting than upsetting, borne up by the voice - or rather, voices - of Pushkin, and the sombre beauty of Markowicz's renditions (to be read and reread). Markowicz bears out what Henri Meschonnic says of translation, its "unique and unappreciated role in revealing how people think in a different language and literature". Unappreciated or not, André Markowicz has spent a decade, and then some, working on this book: three-quarters of the poems translated have never been published in French before - and some never even in the original.

What ties together this 500-page tale of friendships and love affairs, bereavements and quarrels, is an ongoing "conversation", as Markowicz calls it, against all odds. And aren't the intellectual exchanges and affinities, the ardour, cosmopolitanism and tenacity of Pushkin's circle still enduring elements of Russian culture to this day - often against all odds?

-------------------------

English version: Eric Rosencrantz

(Editing by Graham Tearse)

Le Soleil d'Alexandre by André Markowicz is published in French by éditions Actes Sud, priced 28 euros.

For the foreword to the book (in French and in PDF), click here. A poem by Wilhem Kuchelbecker, who perished in Siberia.

Events of interest to translators being held this month in France:

The 28th session of the Assises annuelles de la traduction, a literary translation conference bringing together translators and publishers and other professionals is held in Arles, southern France, from November 11th-13th.

Rencontres littéraires internationales de Saint-Nazaire, an international literary gathering and conference is held in Saint-Nazaire, north-west France, from November 17th-20th.