France went back to school this week, even if for many of the country's 800,000 teachers the return to the classroom on Tuesday was accompanied by a sense of frustration. As a candidate François Hollande promised to make education a priority and under his presidency a number of key reforms have indeed been carried out. These include changing the primary school week from four to four-and-a-half days, reforming teacher training, a programme to reduce educational inequalities between different areas and altering parts of the school syllabus. The new government also pledged to create 60,000 new teaching posts, and 22,000 jobs have already been created.

But despite the reforms – and in some cases because of them – many existing teachers feel they have been overlooked. Salaries have gone down in real terms, many of the new teaching posts have been absorbed by the greater focus on teacher training - the position of trainee teacher has been reinstated – while demographic changes mean there has been an increase in the number of children coming into the school system; 37,000 extra over the last three years. This helps explain why, though last week the outgoing education minister Benoît Hamon told his successor Najat Vallaud-Belkacem that she was inheriting a substantial budget, the education hierarchy was privately warning of a “tense” return to school, admitting that apart from some priority areas the teacher to pupil ratio had “gone down slightly”. Christian Chevalier, secretary general of the teaching union the Syndicat des enseignants-UNSA, spoke for many of his colleagues when he said: “Now it's time for the staff.”

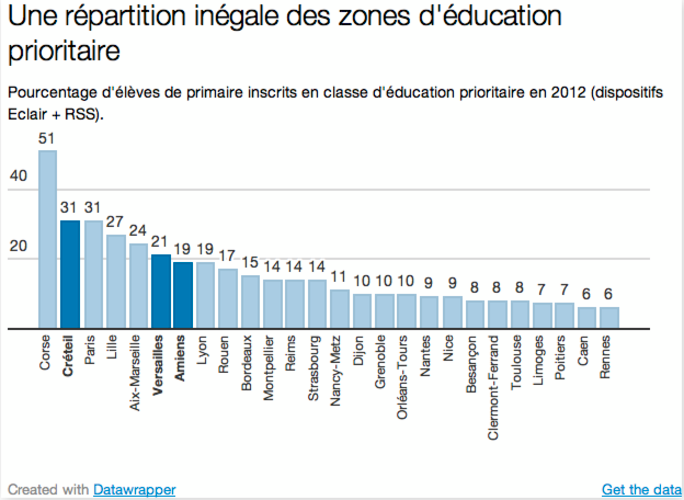

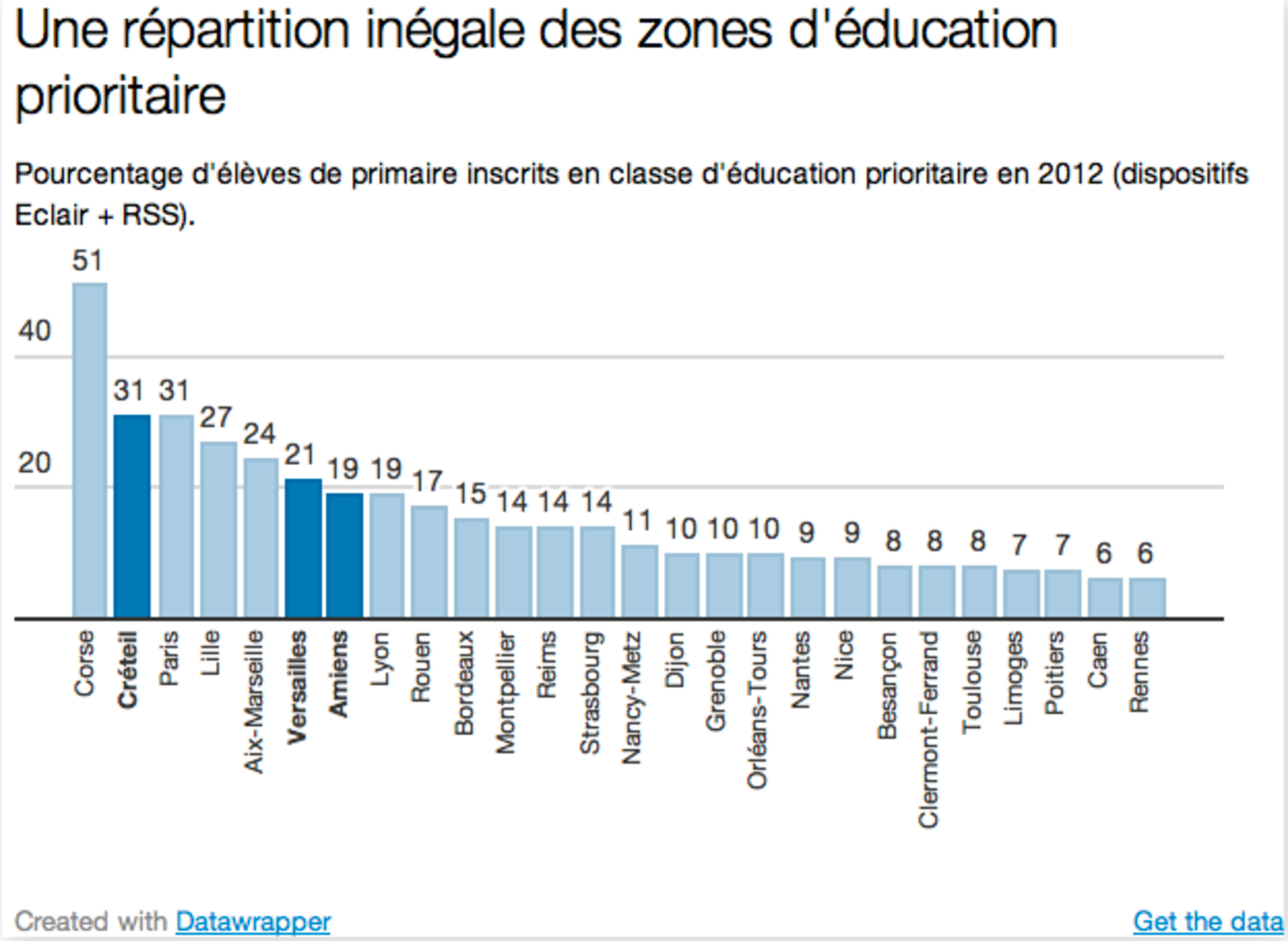

One recurring problem is finding enough well-qualified and experienced primary school teachers to teach in some of France's more deprived areas. The result is that sometimes these areas have to reply on inexperienced and trainee teachers, some of whom have failed to find work as teachers elsewhere. Research by Mediapart has shown the extent to which three academic authorities in particular, Versailles, west of Paris, Créteil south east of the capital, and Amiens in the north of France, have been forced to rely on trainee teachers for the 2014-15 academic year.

First of all it should be noted that this year there are far more trainee teachers around than normal, following a decision by Hollande's first education minister Vincent Peillon to hold two rounds of recruitment exams for would-be teachers in 2014 – the Concours de recrutement de professeur des écoles (CRPE) – instead of the usual one. As a result Versailles education authority, for example, has been able to take on 2,325 trainee teachers this year while its counterpart in Créteil has recruited 2,048. That is nearly four times the number of new primary school teachers taken on by education authorities in other parts of mainland France.

This high level of recruitment among trainees, which is directly linked to these areas' problems in attracting experienced staff, has been achieved by the authorities lowering their requirements for grades achieved in the CRPE recruitment exams. According to figures supplied to candidates - the education ministry itself refuses to discuss the differing requirements of different education authorities – Créteil was prepared to take candidates who scored 6 out of 20 in the exams held in July, Versailles asked for a minimum of 9.2 out of 20 and Amiens required 8.6 out of 20. In the rest of France education authorities require marks between 11 and 13 out of 20 for new primary school teachers.

The result is that these three education authorities had a pass rate among applicants of around 50%, in contrast with the 20% rate seen in more 'selective' areas such as Brittany in the west of France, Aquitaine in the south west and Lorraine in the north east. Moreover, in many cases these deprived areas have recruited teachers who were taking the CRPE exams for the second or even third time, applicants who had given up hope of getting a job in their own region and had instead sought a teaching post elsewhere. After a few years of teaching many of these young teachers are likely to apply to be transferred, either to their native regions or to areas where living costs are lower and working conditions are better. And thus the downward spiral of education in these deprived areas continues.

“I try to reassure myself that teaching far from home, in a ZEP [editor's note, an educational priority zone or zone d'éducation prioritaire], is a great way to learn when you are starting. I prefer that to teaching at Neuilly [editor's note, a well-heeled district just west of Paris] and being faced with ultra-demanding parents, but to be honest I know that I've got a ten-year stretch,” admits Margot, a 25-year-old from the Basque region of south-west France. After two failed attempts to teach in the Bordeaux area, she “reluctantly” decided to come to teach in the Versailles education authority.

Trainee teachers such as Margot who have been recruited for this academic year will spend two-and-a-half days a week in the classroom. But they have been looking after classes on their own for the first days of this new term. “A few days before the new term we were told that none of us would be teaching in CP [editor's note, cours préparatoire, the first year in primary school], in CM2 [editor's note, cours moyen 2e année, the final year in junior school before middle school or collège] or priority education areas, but faced with a lack of staff some have nonetheless been posted in ZEPs,” says this trilingual teacher, who is already thinking of moving to a French school abroad within three years – the minimum period after which she can leave – if she does not get transferred to her home region.

“For many teachers an education authority in a suburb (1) is tantamount to a prison from which one can never escape,” says Christian Chavalier whose SE-UNSA is the second-largest union representing primary school teachers. Yet it is precisely in these areas, given the difficult background of many of the pupils, that the need for staff is greatest.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

In the Amiens education authority half the school population suffer from “economic, family and cultural” problems, putting it among the three worst areas for deprivation in the country according to a report from the DEPP – the Direction de l'évaluation, de la prospective et de la performance – a unit at the ministry of education charged with evaluating pupil performance. At Créteil, some 44% of pupils experience “difficulties in family life and in their social environment” and in some areas of the authority, for example the département of Seine-Saint-Denis, the proportion of young people without educational qualifications varies between 35% and 48%, according to the local district. In the Versailles education authority there is greater disparity in the type of social environments; in the western half of the authority children generally enjoy “economic security and cultural support” thanks to their family circumstances. But in the areas bordering Seine-Saint-Denis or Paris itself – for example the districts of Sarcelles, Villiers-le-Bel or Argenteuil – there is a wide range of social problems, including a high number of single-parent families and considerable poverty, with many families living on less than 10,000 euros a year.

For these reasons the three authorities have, since 1999, been receiving more help than other regions in terms of targeted, priority education. Yet in these predominately urban areas the number of children per class remains among the highest in the country: between 24 and 26 pupils per class across the areas. This kind of context makes it even harder for a new teacher.

-----------------------------------------------------------

1. The French word used, banlieue, means suburb but it often, as here, carries an additional meaning implying a run-down or deprived area, often with a large immigrant population.

'Either the kids treat you like a cop or you are their only role model'

One teacher who became aware of such difficulties “from the first week” is 33-year-old Olivier. He grew up in a rural area and, like many trainees of today, he found himself in 2007 teaching in a ZEP school in the Val-de-Marne département south of Paris with few or no points of reference to help him.

“When you get here you find yourself faced with kids who have absolutely no role model. There are rarely more than a third of parents present at information meetings [editor's note, meetings designed to keep parents informed about developments at school],” he says. “As some are often victimised by their parents, [the kids] either take you for a cop or you become their only adult role model. In such cases it's very gratifying, but you can never take them as far as you want to because you endlessly have to go back and start at zero again for the three-quarters of them who are completely lost. What might have made me stay was not getting paid 2,500 euros a month but the assurance that I'd be able to carry out my job effectively, and for that you'd need a maximum of about ten pupils per class.”

After eight years in the job, and faced with the apparent impossibility of joining his partner who is in Brittany, this primary school teacher who was taking CM1 classes - Cours moyen 1re année, the penultimate year before middle school – seriously considered quitting the profession. Finally, this summer, and thanks to a “stroke of luck”, he was able to leave the Créteil education authority and find a position at Rennes in Brittany and be with his partner.

Over the past decade teaching unions have seen hundreds of similar cases of disgruntled teachers in the suburbs around Paris, and increasingly now in the Amiens education authority as well. The unions want these education authorities to be made more attractive to teachers, starting with improved working conditions – they estimate a typical working week for a teacher in these areas is 44 hours - followed by a salary increase. Current pay works out at between 1,300 euros and 1,900 euros a month net for the first ten years.

The union's pleas have been partially heard. For this new academic year a total of 102 new priority education networks have been created across France, each one linking five primary schools to a middle school (collège in French). In the jargon these networks are known as a 'REP+' for 'réseau d’éducation prioritaire +'. Teachers working within these networks get their bonuses doubled – to around 1,000 euros a year – and work fewer hours, with 18 half-days kept clear of teaching duties, some of which are used for re-establishing links with parents. Classroom teaching is also regularly backed up by an additional teacher whose role is to free up the teaching staff. Another 350 REP+s are planned for September 2015.

But as there are still only nine networks of this kind in Créteil and six in Amiens, their impact remains marginal when it comes to improving the poor image of these education authorities. Until now these areas have been able to compensate for the loss in teaching staff by drawing on an existing reservoir of applicants. But since 2010, when teachers were required to have a master's degree, this reserve of applicants has dwindled away.

“We could develop a specific recruitment procedure for these three education authorities,” says Sébastien Sihr, secretary general of SnuiPP, the leading union for primary school teachers, who describes the situation in these areas as “black spots” that need to be dealt with over the coming years. “Why not organise a pre-recruitment procedure for students from these départements who are taking their degrees, and bring them on via an adapted course until they are qualified.”

Yet neither the unions nor the ministry itself want to change the way recruitment is carried out in regions nor call into question the system – mutation - under which staff can be transferred from one region to another, a rigid and complex process, but one which is based primarily on the wishes of the teachers themselves. It is therefore likely to take years for these authorities to be able to develop a positive image and attract experienced teachers.

How will this be achieved? First of all, say officials, by better communication inside the world of education itself. “I don't understand why Versailles is generally perceived as a vulnerable and deprived area, when if you took an average of the the risk of [pupils] dropping out, it would be better placed than education authorities around the Mediterranean,” says Catherine Moisan, director of the DEPP which has drawn up a region-by-region guide to the social risks involved in pupils failing at school. “There are doubtless other factors that come into play in relation to its attractiveness, such as property prices. The unequal appeal of our education authorities is an issue that must be looked at.”

Then, say the unions, there needs to be an ambitious policy of improving the lot of deprived areas. “The overhaul of the education system is a problem to be tackled in the long-term, and the overhaul of these three education authorities extends beyond the scope of the ministry,” says Sébastien Sihr. “If you don't have a determined public policy that leads towards a greater social mix and which improves access to housing and jobs, you can come up with all the financial incentives in the world – it won't change the overall image that people have of these areas.” In other words, in order to recruit teachers for these areas, they first of all have to be de-ghettoized.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here, with additional material taken from this story.

English version by Michael Streeter