On October 6th 2023, the lower torso of a man, to which trousers were still attached, was found washed up on a beach on the island of Texel, off the northern shore of the Netherlands. Several days later, a sneaker was found nearby with a foot still inside.

DNA tests on the decomposed human remains established they were from two different men, and one possible hypothesis of where the body parts came from was the sinking, two months earlier, and 300 kilometres south-west of Texel, of a boat carrying migrants on a clandestine crossing from France to Britain.

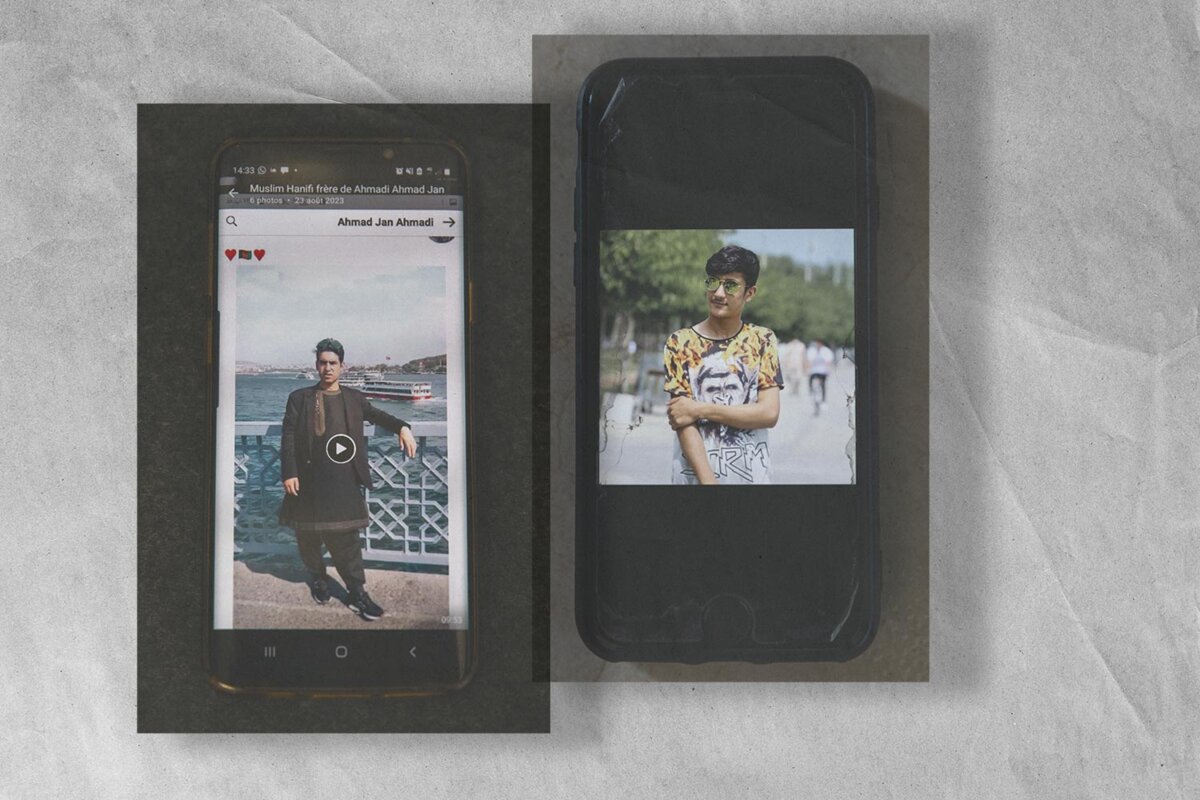

For it was on August 12th 2023 when an overcrowded inflatable dinghy, carrying around 60 people, sank in the Channel off the French port of Calais. Six Afghan nationals perished in the sinking, while another two Afghans were reported missing and remain so today. They are Ahmadi Ahmad Jan, 29, and Samiullah Abdulrahimzai, 22.

They were identified as missing in the weeks that followed the tragedy, and their families were traced by Mohammad Amin Ahmadzai, the head of an association, the ASCIA, based in northern France which offers aid to the many Afghan migrants who arrive in the region seeking a passage to Britain. In August 2023 that Ahmadzai’s main activity became that of principal go-between with the local authorities in their attempts to identify the victims of the regular sinkings.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Ahmadzai tracked down the families of the two missing men in Afghanistan, where the Taliban had returned to power in the summer of 2021. Subsequently, after the gruesome discoveries on the shore of Texel, and in conjunction with the Dutch police and the French maritime gendarmerie – the latter being in charge of the missing persons investigation – he asked the relatives to collect DNA samples for analysis to see if any matched the body parts.

The impossible attempt to compare DNA

The family of Samiullah Abdulrahimzai took a toothbrush to the offices of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in the Afghan capital Kabul in early 2024, in the hope they could develop a genetic code. But, recounted Ahmadzai, the Red Cross told them it was incapable of doing so “due to the situation in the country and the lack of technical means”. Ahmadzai advised them to organise the sending of DNA samples to France by themselves.

Several of Abdulrahimzai’s brothers later sent two toothbrushes and a comb, wrapped in a plastic bag, to an address in Iran, where one of their cousins, who lives in France, travelled to pick up the parcel. The cousin then delivered it to Ahmadzai who in turn, in September 2024, passed it on to the gendarmerie investigators. In December came the news that the genetic codes taken from the toothbrushes and comb did not match either of the body parts found in the Netherlands. Abdulrahimzai’s cousin in France and members of his family in Afghanistanin said they had still, by this month, not been informed of this.

However, a Dutch police source close to the investigation said the negative result could not be regarded as definitive and did not remove the possibility that the remains washed up on the beach included those of Abdulrahimzai. That was because of the conditions in which the DNA samples were sent, and the uncertainty of their provenance.

Meanwhile, the French investigators established a link to Ahmadi Ahmad Jan, the other Afghan who went missing in the August 2023 sinking, in a mobile phone found in the trousers attached to the lower torso found on the beach in Texel. But the above-mentioned Dutch police source said that here, also, the absence of a reliable DNA comparison rendered identification of the missing man impossible.

The family of Ahmadi Ahmad Jan did not send DNA samples for testing, despite the fact that one of his brothers works for a legal practice in Kabul. “Our family is still waiting for news,” said the latter, contacted last year for this report. Contacted again in May this year, he repeated that they had still received no word from the French authorities. “No-one has contacted us,” he said.

In such cases in the Netherlands, the authorities place a priority on the identification of the corpses and their return to their families. In France, the investigation into the August 12th 2023 sinking is centred on establishing the responsibility of human trafficking gangs, and is carried out under the auspices of the “National Jurisdiction for the Fight Against Organised Criminality”, JUNALCO. Its aim is to trace back through the trafficking network the roles of the ones and the others and to ascertain their legal responsibility in the deaths of the six Afghans who were found drowned.

For the Dutch police, no reliable evidence has been found to identify the body parts found on Texel in October 2023. Yet in the official case report of the French judicial investigation, which ended on May 5th and which is now awaiting the advice of the public prosecution services regarding the charges to be brought, it is stated that one of the two body parts is considered to be that of “a victim” in the August 2023 sinking.

Eight people have been placed under investigation, and it is only after the prosecution services advise on their cases that the examining magistrates in charge of the probe will make the final decision on who should be charged and sent for trial. Among the eight suspects are two migrants who allegedly captained the dinghy. Under French law, that constitutes human trafficking and, if tried and found guilty, they each face a maximum prison sentence of ten years.

In France, the slow progress of investigations, the failure to keep families properly informed and the many different people to whom they must turn for information were characteristic of the cases of fatal migrant boat sinkings in the Channel between 2020 and 2024 which Mediapart examined.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

On paper, the procedure for identifying a corpse is straightforward. When a body is found on a beach, an investigation is opened by the local public prosecution services and handed to the police or gendarmerie services. The corpse is transferred to a medico-legal institute – a mortuary where autopsies and forensic examinations are carried out – and which also works under the control of the prosecution services.

A series of bodies washed ashore after dinghy sinking

In the early morning of October 23rd 2024, an inflatable dinghy heading from the French coast for England carrying what some in the boat estimated to be between 60 and 70 people, began taking on water while just a few kilometres off Calais, and rapidly began sinking. French maritime rescue services saved 48 people from the dinghy, and the official toll of the incident was first reported as three dead and one injured. Mediapart would soon reveal that in fact at least 13 other people on board the boat were missing, bringing the possible total of dead to 16. Bodies were subsequently washed up along the Channel beaches of the Côte d’Opale in north-east France. On November 2nd, a corpse was found on the beach at Sangatte. On November 5th, two more corpses were found in the sea off Calais, and another was discovered floating in British waters close to Dover. The following day, a body was found on a beach at Calais, while two others were retrieved from the sea close to the port.

In all, between October 23rd and December 21st last year, the bodies of 14 people were recovered.

Police and gendarmerie services were assigned to identify the victims but, because they are also regularly ordered to evacuate illegal campsites set up by migrants, they found themselves with very few possibilities of finding potential witnesses who might have known those who drowned. As a result, the investigations turned to seeking information from the local network of associations and NGOs which offer aid to migrants in this corner of north-east France, and whose volunteers are in contact with the migrant population on an almost daily basis. The Red Cross, which is active in the region, also plays a role of interface between the authorities and the associations.

The authorities leave the people active in solidarity [with migrants] to try, as best they can, to obtain information,” said Flore Judet from one of the most active associations, L’Auberge des migrants. “Yet the only means [the volunteers] have is to talk with the exiled, to try and build contact, something which the authorities unfortunately don’t do today.”

The prosecution services, which oversee each move by the police or forensic services to identify victims, readily admit they depend upon humanitarian associations and their volunteers for information. “The ‘migrant circle’ has a complicated relationship with the investigating services, for different reasons,” said Guirec Le Bras, a former public prosecutor in the Channel port of Boulogne-sur-Mer, in an interview in February 2024. “It’s for that reason that I have few descriptions of disappearances that arrive naturally.”

Mehdi Benbouzid, is a public prosecutor in Saint-Omer, an inland town about 40 kilometres south-east of Calais. Concerning the identification of corpses, he said “there are investigations that are carried out within the associations aiding migrants in the Dunkirk and Calais surrounds, to see if they recognise people. At other times it is they who come to us to say that they were supposed to have received a call from England from so-and-so, it could be him who has disappeared. It goes both ways.”

But for some association members, the cooperation is not as fluid as Benbouzid described. “Contact with the authorities is complicated,” said one, speaking on condition her name was withheld. “It’s a little like fishing with a line, you don’t know who is responsible for what.”

A sorry lack of communication

As of recently, the French authorities have attempted to improve procedures. This includes the creation of a special gendarmerie unit, the NODENS, dedicated to the identification of bodies found on the Channel coast. It is made up of five investigators, assigned to cases by the public prosecution services, and working under the authority of France’s maritime prefecture for the Channel and the North Sea.

The NODENS is involved in the identification of corpses that were found in the weeks following the October 23rd 2024. Seven months on from that tragedy, ten of the 14 bodies found remain unidentified.

Behind such bare statistics are the families of the deceased who, back home, thousands of kilometres away, have no news of what became of their children, siblings, spouses. One of those who disappeared in the October 23rd sinking last year was Amanuel, a young Ethiopian. “I cry every night,” said his father, Terfe Berhe, speaking from the Ethiopian capital Addis Abeba. He moved to the city in November to be registered with the Red Cross offices there, where he hoped to soon receive a kit for sending DNA samples back to France to check against the bodies found. Close friends of Amanuel who now live in Belgium have provided financial help to his father to allow him to remain in the capital.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

It is the NODENS team which is in charge of investigating the case of Amanuel, and as such the sending of a kit to his father to provide DNA samples. But in February, five months after the disappearance of his son, Terfe Berhe had still not received anything and left the capital for his home. “I waited so long for this DNA kit,” he said then. By this month he was still waiting and has not been given the name of anyone he might contact. The NODENS failed to respond to Mediapart’s request for an interview.

Innovating tools for the process of identification

Numerous actors involved in the process of identification of those who die on their journey to a hoped-for better life elsewhere are calling for new, more effective methods to be employed. Professor Caroline Wilkinson from Liverpool John Moores University is an expert in facial identification and head of the university’s ‘Face Lab’ research centre. She directs a pan-European project called Migrant Disaster Victim Identification Action, a network of experts working on novel techniques for identifying anonymous corpses found in certain European border-crossing areas and providing training to use them. “It is thought that at least 25,000 people have died in the last ten years crossing the Mediterranean alone, and that’s not even accounting for those who die on land and other routes,” Wilkinson told British daily The Guardian in January. “Only [about] 25% of those are ever formally identified – and those are just the ones where the bodies are found. There’ll be thousands of other bodies that have never been recovered from those migrant disasters.”

While current, legally acceptable identification methods are focussed on DNA, fingerprints and dental records, a number of other tools exist, such as studying photos published on social media, the mapping of maritime currents, and tracing through visual marks, such as tattoos, on corpses.

In Spain, the Red Cross has been using since 2023 new software jointly developed by the ICRC and the Lyon National Institute for Applied Sciences in France aimed at improving the identification process. Called SCAN (for “Share, Compile and Analyse”), it is based on sharing information about boat sinkings in real time, along with the accounts of survivors, and communication with those, such as activists with humanitarian organisations, who have been contacted by people close to those who have disappeared.

Pathologists and scientific researchers are among those who insist on the necessity for a wider sharing of skills in the domain of identifications, and for a Europe-wide coordination of such activity. “At a European level, it would be easier if we had greater possibilities for exchanging data,” commented Tania Delabarde, a pathologist with the Paris medico-legal institute. She said plainly that “the means are not employed” for the identification of migrants who die in the Channel. “We would like to awaken consciences,” she added. “Those people are dead, and what’s more, their identity is denied.”

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse