The French press is in crisis, with readers fleeing the newsstands, revenue collapsing and titles changing hands amid ever cheaper sell-offs. Vincent Truffy and David Medioni argue here for a re-think of the role and tools of the profession and regret that, instead, media owners and editorial managers continue to stubbornly grasp onto an obsolete model.

-------------------------

A little more than two years ago, at the end of 2008, President Nicolas Sarkozy brought together government members and the country's media professionals in a project aimed at establishing the state and future of the ailing French print press.

Called ‘the States General of the press' (Etats généraux de la presse), it involved a series of round-table discussions, followed by detailed reports, sector by sector. Its brief was to carry out an autopsy of the problems and to suggest what reforms were necessary to nurse an ailing industry. The work was completed early 2009.

At the time, print sales were suffering and advertising was dwindling. The reports of the problems were piling up, all bearing witness to the quagmire the sector was sinking into.

Nicolas Sarkozy warned that the State "will not impose any sclerosis, any corporatism, any bad habits", in order to "free-up solutions" for the press: "It's not a question of writing an umpteenth report on the subject, even though some very good ones have been written in thepast," he said. "It's a question of agreeing on a certain number of changes to be got under way immediately."

Two years have passed since the announced solutions supposed to offer a turnaround. The press is now no longer ailing, it is moribund. Newspapers are worth less today than the debts they are accumulating. While the Amaury group hopes to receive 200 million euros from the sale of Le Parisien daily newspaper, bids are hardly reaching half of that sum. Edouard de Rothschild,who invested 31 million euros in left-wing daily Libération,is ready to let a shareholder in as his equal for only 12 million euros. The journalists of the self-estimed daily of reference, Le Monde, relinquished their sacrosanct independence for 110 million euros, which also included all the rest of the group (iTélérama, Courrier International, La Vie). While financial daily La Tribune is changing hands for a token euro.

But the highest price in all this will be paid by the readers.

Publishers manage to find some consolation by saying that the thirst for knowledge has not decreased:according to a study by French media research organisation EPIQ, one out of two French people read a daily every day, three out of four read one a week. So why sales have fallen 17% in five years? Convinced that informationis no longer worth paying for, they no longer regard general news as anything more than an obsolete appendage of magazine and consumer pages meant to attract recalcitrant advertisers.

The press is at death's door as a result of having lost sight of its political and social purpose. "We have tothink today of a way to finance quality universal information," explains Bruno Patino, who was in charge of the digital pole of the Etats généraux. "Universal means information that covers allsubjects, all layers of society, all geographical zones, with no blind spots. Quality means regular information that guarantees a form of monitoring, of surveillance of the functioning of society and those in power. Because this is the real reason for being of the press, as [Jürgen] Habermas explains, to circulate information that structures the public space, nourishes debate, inform collective choices".

'Printing and distribution costs monopolised attention'

The press is dying for having believed its economic model would last forever. Information is sold to readers and readers are sold to advertisers. But information comes from elsewhere, through other channels, with other modes of validation. Continuous radios, and the web, with its social media, have taught readers how to inform themselves as fast as journalists. An increased distrust of the go-betweens, the gatekeepers, has done the rest. A press that doesn't keep up with the evolution of its world is condemned.

And advertising has found other outlets, atomised into thousands of blogs, Facebook pages, specialised television and radio stations, so that nobody can make a living from it anymore. "By limiting reflection to those who are making the press of today and, above all, of yesterday, they have deprived themselves of the creativity and innovative capacity of other players, who remain on the fringes of the system," notes Didier Mathus, vice-president of the Socialist Party group at the French parliament, in charge of media. "The press is still based on an economic model that stood still between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 21st century, and which is destabilised today by freesheets and the digital media. Today we can't imagine reverting to a stable system like the one the press knew. Techniques, usage, innovations and demands are bound to change all the time. We need to take heed of them."

Patrice Martin-Lalande is an MP with France's ruling UMP party, and is the rapporteur on media issues for the French parliamentary finance commission. "The Etats généraux don't resolve all the problems, for all time," he says. "Their role was to speed things up, but their existence needs to be prolonged in order to continue the work of co-creating tomorrow's press. The speed of change in the media sector - and the tendency of the press to resist change - imposes urgency."

"The Etats généraux have allowed the profession to de-freeze, to eliminate out of date analyses, to define what issues are at stake and to plot the path to addressing these issues. Printing and distribution, which represent 60% of the cost of the press, have monopolised publishers' attention. But what counts are the contents. The future of the press is largely dependent on its online cousin, because, by saving that cost, it will be able to offer more attractive prices. And yet the public also needs to have validated contents, with editorial responsibility."

'A perpetual round of entertainment'

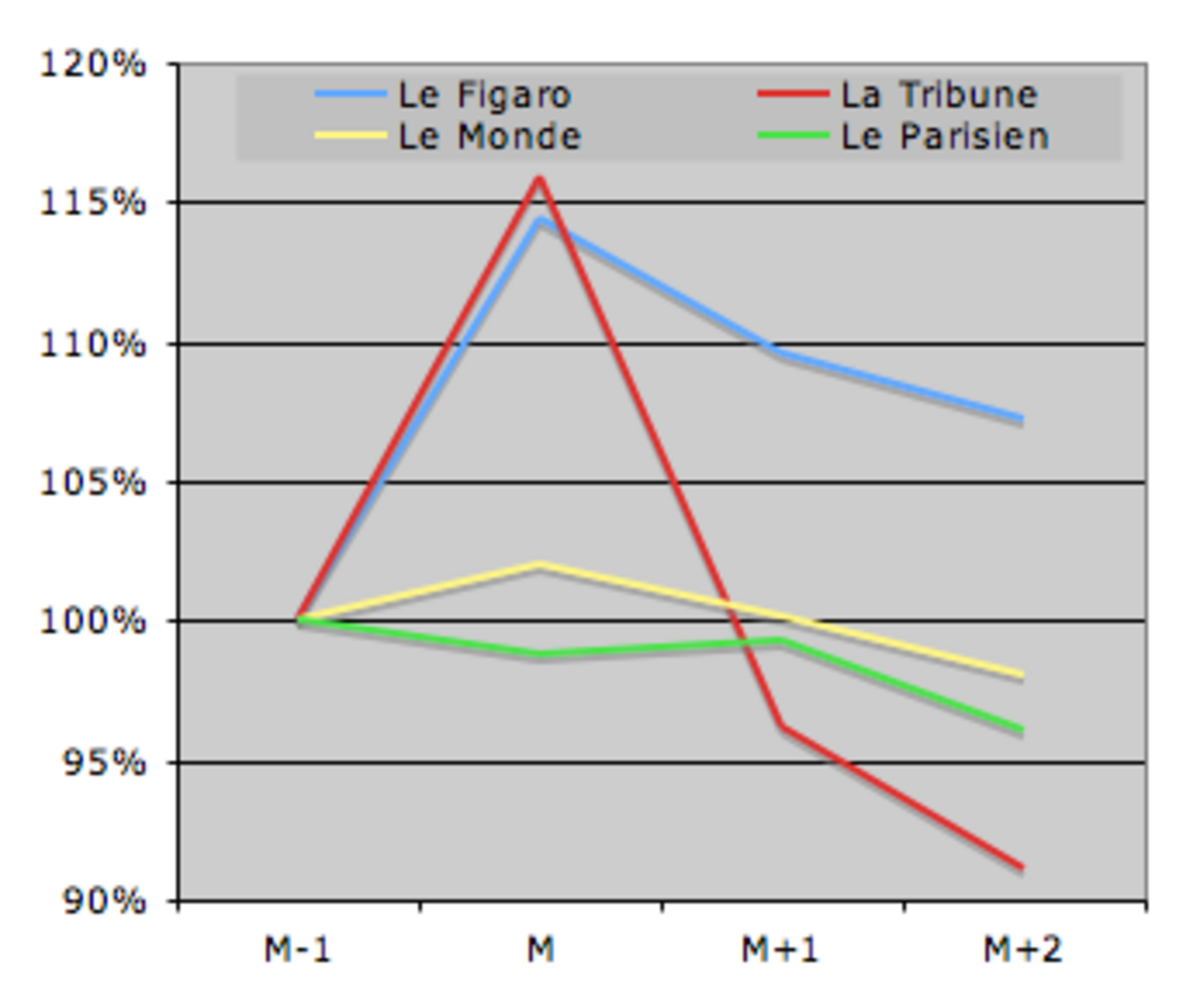

The press is dying as a consequence of failing to rethink its editorial offer. New formulae blossom every year; La Tribune, then Le Figaro, followed by Le Monde, and Le Parisien and, for France Soir, twice in less than a year. All of them are amply subsidised by the State. And yet, while sales simmer for a few months, they soon die down, and subsequently drop faster and faster than before, which is a sign that publishers have not approached the problem from the right angle.

Faced with a revolution in people's habits of using the media, the press is suffering from continually patching up a usage that the great majority no longer practice. "Today new formulae serve only to slow down the ineluctable erosion of readership," argues Jean-Clément Texier, a banker and media expert.

Patrick Eveno is a lecturer at the Sorbonne University of Paris 1 and a specialist in media economy and history studies. "I think we need to start really putting our heads together to devise the best possible equation that can be made with readers' demands and editorial offer," he comments. "To my mind, the profession urgently needs to equip itself with an applied research system to invent the press of tomorrow."

Jean-Marie Charon, a media sociologist with the French National Scientific Research Centre (CNRS) says it is necessary "to reaffirm that a journalist's first role is to set the agenda, to get the news out, to put it in perspective, to analyse it and to make it understood."

This is all the more needed in order to escape from the copy-cat news habits of the press, the panic of missing the story. The slope becomes all the more slippery by the cult of the web buzz, now considered the only way to get mass attention.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Take for example the TV interview last autumn in which former justice minister Rachida Dati used the word "fellation" instead of "inflation"; the media machine became frenzied, with websites (left and below) and TV news programmes showing the images over and over, radio and newspapers looking back on all the previous slips of the tongue politicians have made and that have become famous.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

In his acclaimed 1985 book ‘Amusing ourselves to death', the US media theorist and culture critic Neil Postman wrote: "When a population becomes distracted by trivia, when cultural life is redefined as a perpetual round of entertainments, when serious public conversation becomes a form of baby-talk, when, in short, a people become an audience and their public business a vaudeville act, then a nation finds itself at risk; culture-death is a clear possibility."

Or, to quote from Democracy in America by the 19th-century French political thinker Alexis de Tocqueville: "I seek to trace the novel features under which despotism may appear in the world. The first thing that strikes the observation is an innumerable multitude of men all equal and alike, incessantly endeavoring to procure the petty and paltry pleasures with which they glut their lives. Each of them, living apart, is as a stranger to the fate of all the rest."

The 20th-century Greek philosopher and economist Cornelius Castoriadis described the "inexorable rise of insignificance": everything has the same worth and everyone says the same thing, to hell with ranking.

-------------------------

Graph: The OJD stands for the Office de de Justification de la diffusion, an officially-recognised body for the evaluation of circulation and readership of the French press.

1: Democracy in America, Volume II, Book Four, Chapter VI, ‘What Sort Of Despotism Democratic Nations Have To Fear'.

The iPad dream turned sour

Finally, the press is dying from not seeking salvation from beyond what is in the public spotlight today: from believing that a tool like the iPad will renew the interest of readers, and restore its ‘brands' to a central place in the information economy.

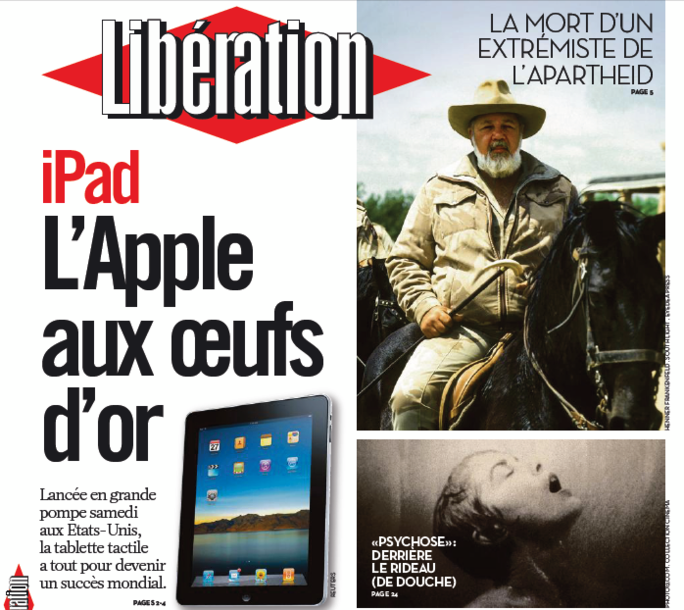

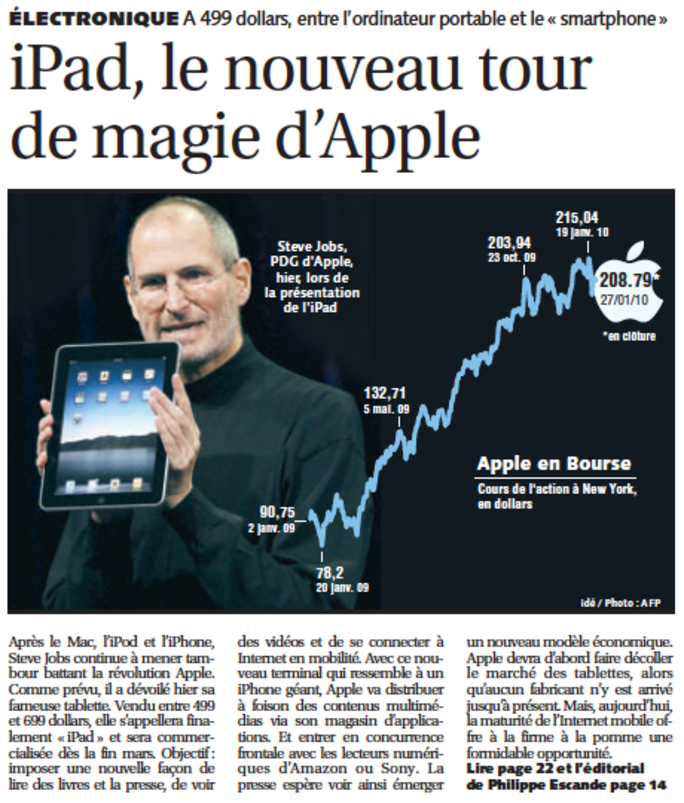

The manner with which the press covered the launch of the Apple pad shows how publishers envisage the future. "Revolution", "new era", "magic" - there was no restraint, the common cause was clear: the iPad would impose itself as the saviour of a moribund press, because it allowed for the charging of readers.

For the time being at least, the major free applications for mobile phones have found an audience (one million visitors per month for Le Monde, 300,000 each for Le Parisien and L'Equipe), while readership plummets in the wake. In the United States, the sales of magazines on iPads are collapsing to a few thousand a month at best, after peaks that reached 100,000 downloads for the first issue of Wired.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Six months on the iPad is considered by publishers as being, at best, a stream part-feeding a larger river of revenues.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

They complain of finding themselves (along with Apple's 30% commission) prohibited from taking on any new subscriptions outside of its payment system, and a fixed-price grid. All of which are greater constraints than the ones they are leaving behind with printing and distribution.

All of which is miles away from the magic takings some predicted. Before the 2000 bubble, publishers were talking about the internet as a new Eldorado, with staggering readership figures, almost zero cost and insane returns.

Ten years later, web and paper editorial units are still working out how to work together, while their media managers are pondering how

to break even after having deliberately destroyed the value - monetary and symbolic - of journalism by publishing ‘for free' (at least, not having ‘contents' financed directly by readers, and less and less by advertisers). These contents cost more and more to produce and already sell on news stands. Hence the argument that readers weren't paying for information, but for the support (paper), or the service (the availability of a newspaper).

For the time being, the state of the press in France is akin to a lot of fumbling in the dark for a magical wand.

-------------------------

English version: Chloé Baker