At the last presidential election in 2012 the Left received its biggest level of support from the least well-off voters. At the time this electorate saw the socialist François Hollande as the candidate who “defended poor people” and “the workers” and was strong on social issues, and they felt the Left “had a heart”(1). But after three years of the Hollande presidency the link was broken. At the regional elections in 2015 this electorate turned towards the far-right Front National (FN). In the first round of the French presidential election on April 23rd, there is a strong possibility that they will again back the FN's candidate Marine Le Pen.

Two studies suggest this, one carried out after the 2012 presidential election and the other after the regional polls. Both use a measure of poverty or social insecurity known as EPICES - Évaluation de la Précarité et des Inégalités de Santé dans les Centres d’Examen de Santé, an evaluation of poverty and health inequality among individuals that is conducted at social security health examination centres.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Originally developed to detect the social vulnerability of people undergoing health examinations in those social security centres, the EPICES measure is now used as a multidimensional social indicator. It does not just measure financial poverty, but also social insecurity in terms of housing and access to health, as well as social and cultural isolation. It is carried out in the form of eleven simple questions with a yes or no answer. The weighted responses then enables each person to be allocated a poverty score that goes from 0 (no poverty) to 100 (maximum poverty and insecurity).

Enlargement : Illustration 3

In the sample from the 2015 study, which represents people registered on the electoral roll, the average score for this indicator is 22. If one divides the individuals into five equal groups or 'quintiles' ascending by the degree of poverty, the score goes from zero in the first quintile, containing those who are not poor, to 49 in the final fifth, that of the “very poor”.

When one looks at the details, the differences between the groups are very striking. All those in the first quintile live as part of a couple, they own their own homes, they have gone on holiday, played sport and been to a show in the last twelve months. None has a problem making ends meet at the end of the month, and if they are in difficulty they know where to turn.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

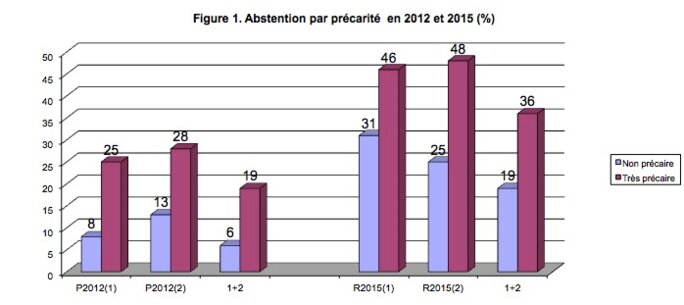

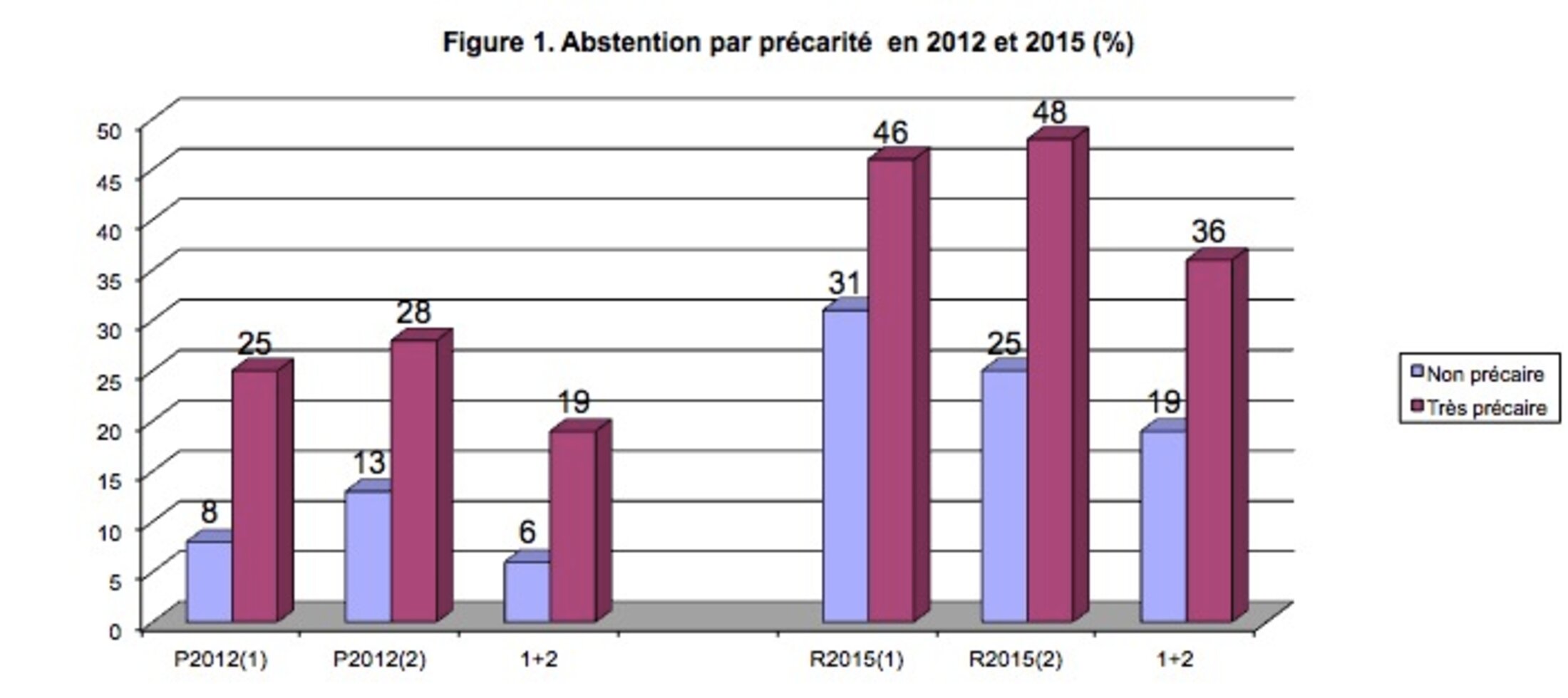

At the other extreme, in the fifth group, some 55% of those surveyed lived alone, 36% owned their homes, 40% had played sport in the last year, 30% had gone on holiday, 39% had seen a show, half had no one to count on in case of a problem and 76% had financial difficulties. The difference in relationship towards politics between the two groups is just as marked (figures 1 and 3). Whatever the election, the main effect of poverty is to render a person more remote from politics, making them less likely to visit the polling booth. In the first round of voting in the 2012 presidential election the abstention rate among the least poor and insecure was three times lower than among the poor, and in the second round there was still a gap of 15 points. The proportion of consistent abstainers, who did not vote in either round, goes from 6% in the first group to 19% in the second (figure 1).

The 2015 regional elections saw a much lower turnout than the presidential poll, but there are still similar differences in the relative levels of participation. This is especially true in the second round where the abstention rate among the very poor is 23 points higher than the better off. The more impoverished one is the less one makes one's voice heard, the less one counts. Social exclusion feeds political exclusion.

-----------------------------------

1. See 'Les Inaudibles. Sociologie politique des précaire' ('The Inaudible. Political Sociology of the Poor') by academics Céline Braconnier, Nonna Mayer, Paris, Presses de Sciences-Po, p.211.

In 2015 poorer workers also abandoned the Left

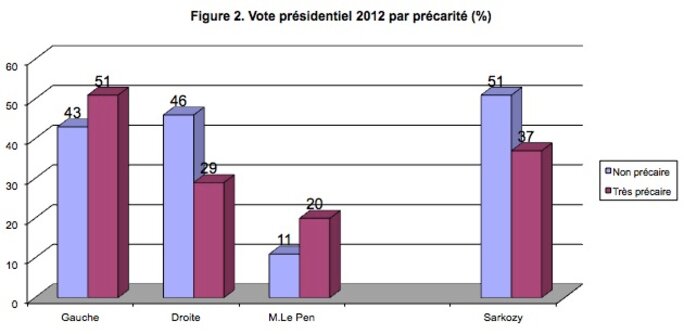

Poverty also has a major impact on voters' electoral choices. In 2012 support for the Left regularly rose according to the level of poverty, and it was among the least well-off that the Left scored most votes. In the first round of the presidential election that year 51% of the very poor voted for a socialist, green, radical-left Front de Gauche or Trotskyist candidate, compared with 43% of the better off. In the second round 63% of the worst off voted for François Hollande, while his defeated opponent Nicolas Sarkozy was narrowly ahead when it came to the better off.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

As for Marine Le Pen, she fared better in 2012 with the very poor than with the better off, with 20% support in the former group against 11% in the latter. But she did even better – 24% - with the second-last quintile who are somewhat better off than the poorest, and who have a EPICES score which is on average three points below the threshold conventionally used to indicate poverty, which is 30 points.

Perhaps most significant is the fact that when you take into account other characteristics of those in the study sample that might influence their vote – age, job, religion, gender, qualifications – the issue of poverty still had a statistically significant impact on whether people voted Left or Right in both the first and especially second round of the presidential election in 2012. Yet poverty was not a specific indicator of whether someone voted for Marine Le Pen, with a person's qualifications much more determinant of whether they voted for the far-right candidate.

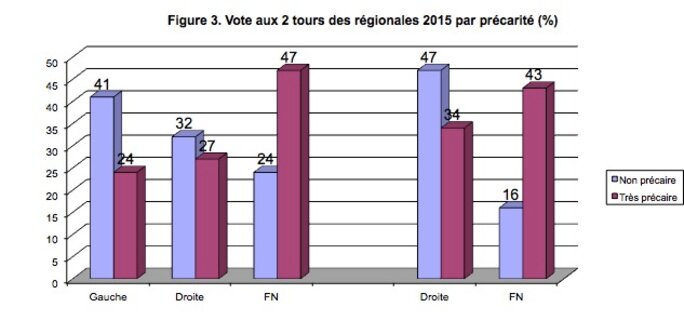

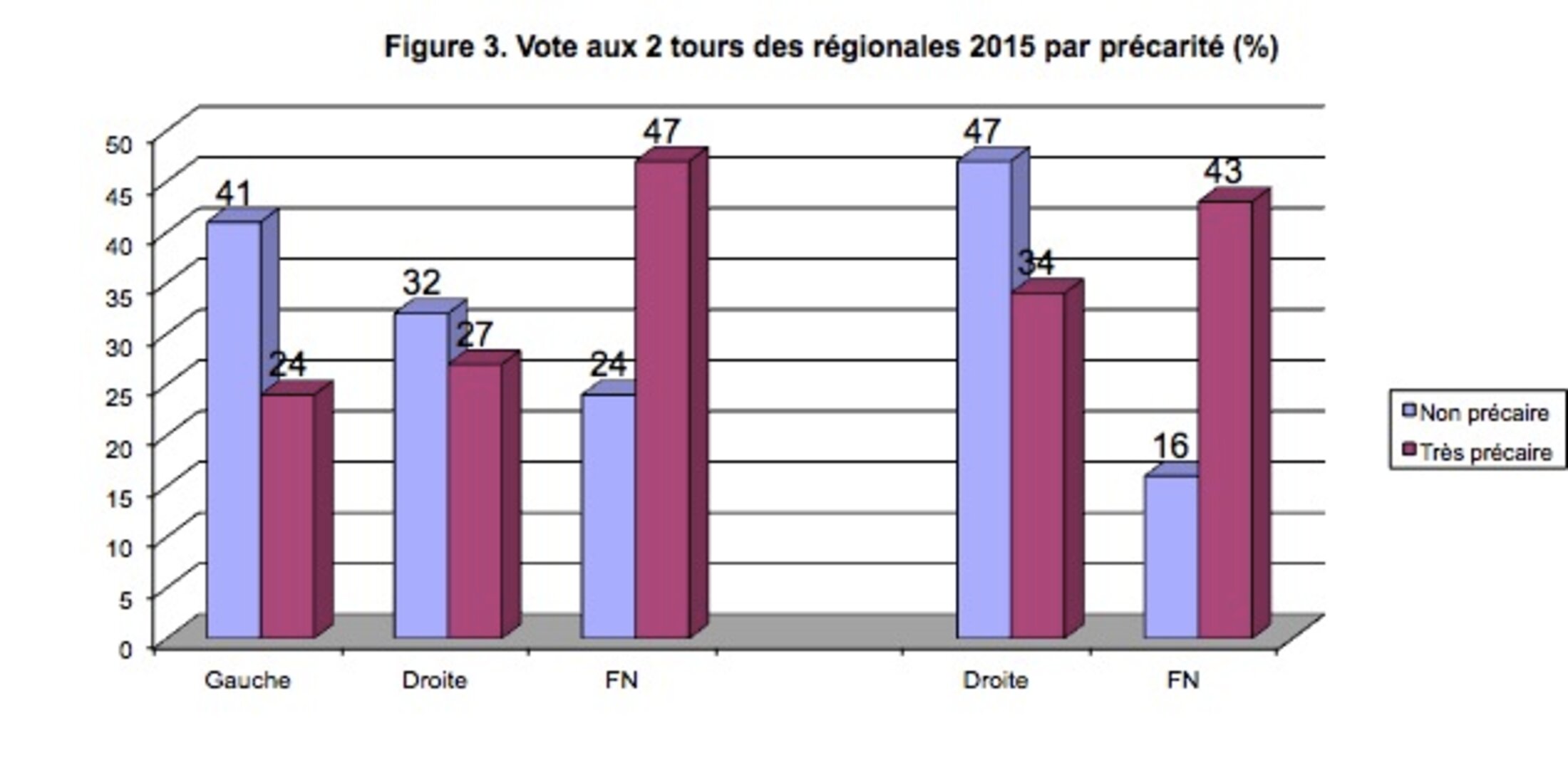

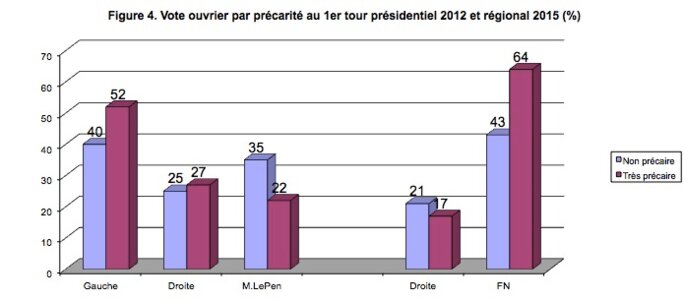

But three-and-a-half years later that all changed. In both the first and second rounds of the December 2015 regional elections we saw a strong and significant inverse relationship between a person's vote and their level of social poverty. The scores of the Front National went up in line with the degree of poverty, going from 24% among the better off to 47% among the poorest in the first round, and from 16% to 42% among the same groups in the second round (figure 3).

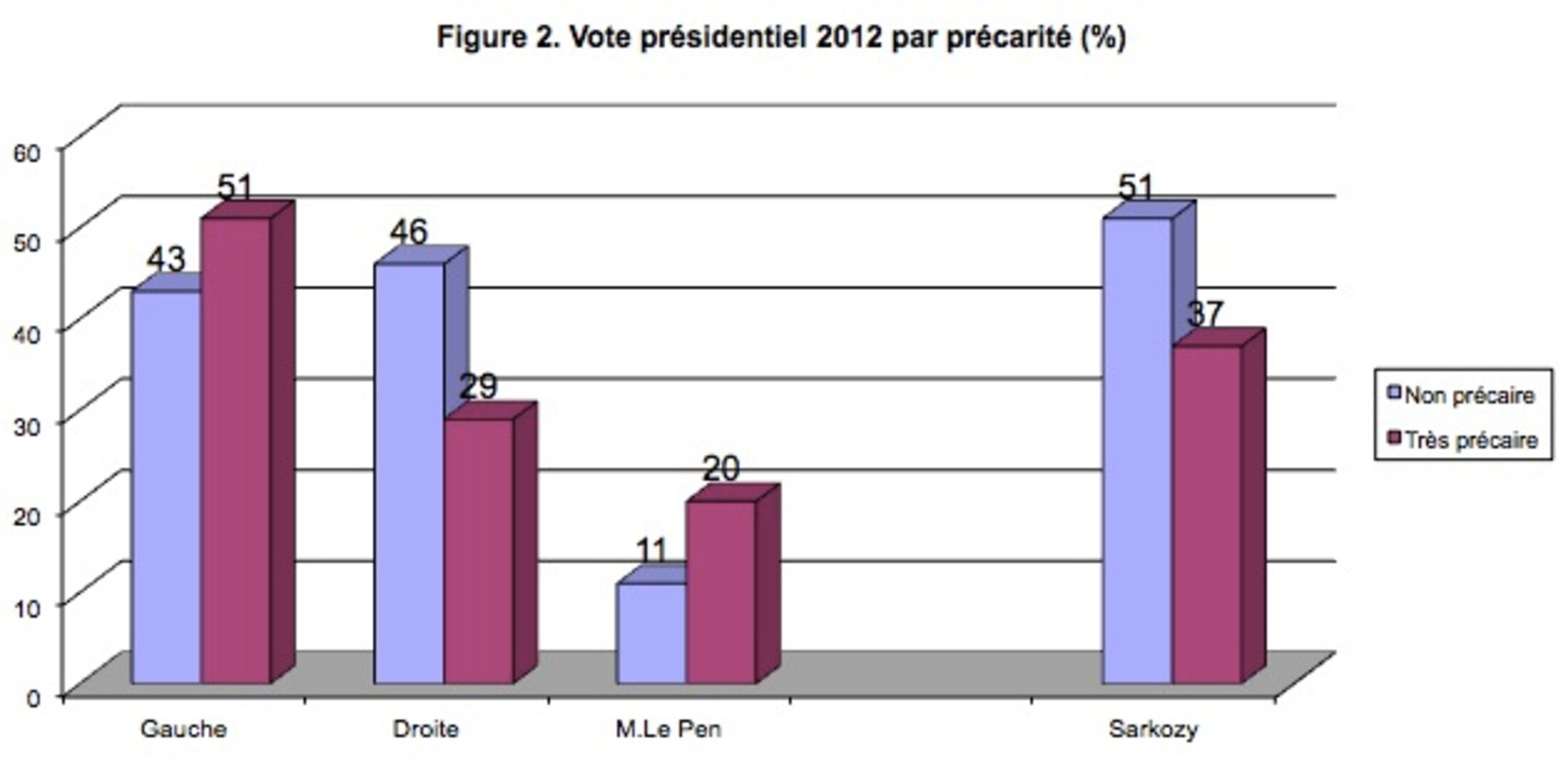

This turnaround is spectacular when it comes to workers. This is a group which is particularly vulnerable in economic terms and who in 2015 scored 6 points above the average in the poverty study sample. Ye it is also a disparate world, which is affected by poverty to varying degrees, which translates into marked political differences. In overall terms, as researcher Florent Gougou has shown, since the end of the 1970s the close links between the Left and workers have gradually grown thinner, yet in 2012 a majority of poorer workers (those scoring 30 or over on the EPICES scale) backed the Left. In the first round 52% voted that way, against 40% for the better off, and in the second round 63% of this category voted for François Hollande.

In the same election Marine Le Pen doubled her score among the better off workers, attracting 35% support from them against 22% of the worst-off workers (figure 4). These workers have some qualifications and material comforts but they fear being dragged back down the social ladder that they found so hard climbing. But in 2015, this was no longer the case. It was then the turn of the poorer workers to abandon the Left, who attracted just 17% of their vote in the first round of the regional elections. Meanwhile Marine Le Pen's electoral share of these voters reached a new record of 64%. A barrier had come down.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

One naturally has to treat these figures with some caution. The abstention rate in the first round of the regional elections was 50% for all electors and 59% for workers, according to academic Pierre Bréchon, and was doubtless even higher among poorer people. So in the first round of that election Marine Le Pen received the votes of no more than a quarter of the poorer workers registered on the electoral roll. But even at this reduced level, this electorate is like a mirror image of the changes which has affected the Left as a whole during the Hollande presidency.

While it is true the current presidential election appears particularly uncertain, all the opinion polls nonetheless confirm the continuing increase in the number of workers overall who are intending to vote for Marine Le Pen. For April's first round vote that number has now reached 40%, against 27% of the electorate as a whole who seem prepared to vote for her. If Marine Le Pen does make it through to the second round in May then the only socio-professional group in which she looks set to win a majority of the vote is among workers. If in that second round she faces the independent candidate Emmanuel Macron she is forecast to pick up 55% of the workers' vote, a figure rising to 65% if her opponent is instead the conservative candidate François Fillon.

--------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter