According to Jean-Pierre Farandou, France's minister for solidarity, people without children do not need to give presents at Christmas. In its relentless hunt for savings in its 2026 budget, the government is considering limiting the traditional Christmas bonus from the state to just those households with children. Normally it is paid to all those receiving certain welfare benefits, including recipients of the Revenu de solidarité active (RSA), the Allocation de solidarité spécifique (ASS) and the Allocation équivalent retraite (AER), and to jobless people whose entitlement to unemployment benefit has run out. The amount paid can vary from around 150 euros to 380 euros in some cases, depending on how many children a family has.

Even though this cost-cutting measure seems unlikely to be approved by MPs, it reveals a growing disapproval of and open scorn towards the “childless”, who have become easy targets for politicians in search of scapegoats. For instance, culture minister Rachida Dati, the rightwing Les Républicains candidate for the Paris mayoral election, declared on November 2nd that the “city’s lifeblood” had apparently “left Paris”.

She lamented how the city had lost “more than 125,000 inhabitants” and, worse still, that “30,000 children have gone”. The minister appears to view this youth exodus as a curse that will lead to decline, and that the French capital will no longer be a city that “makes the world dream”. And she depicted a future she saw as less than desirable. “Are we resigned to having a city of single people on bikes who work ten minutes from home?” she asked, as if childless users of eco-friendly transport have now becoming the ultimate objects of scorn.

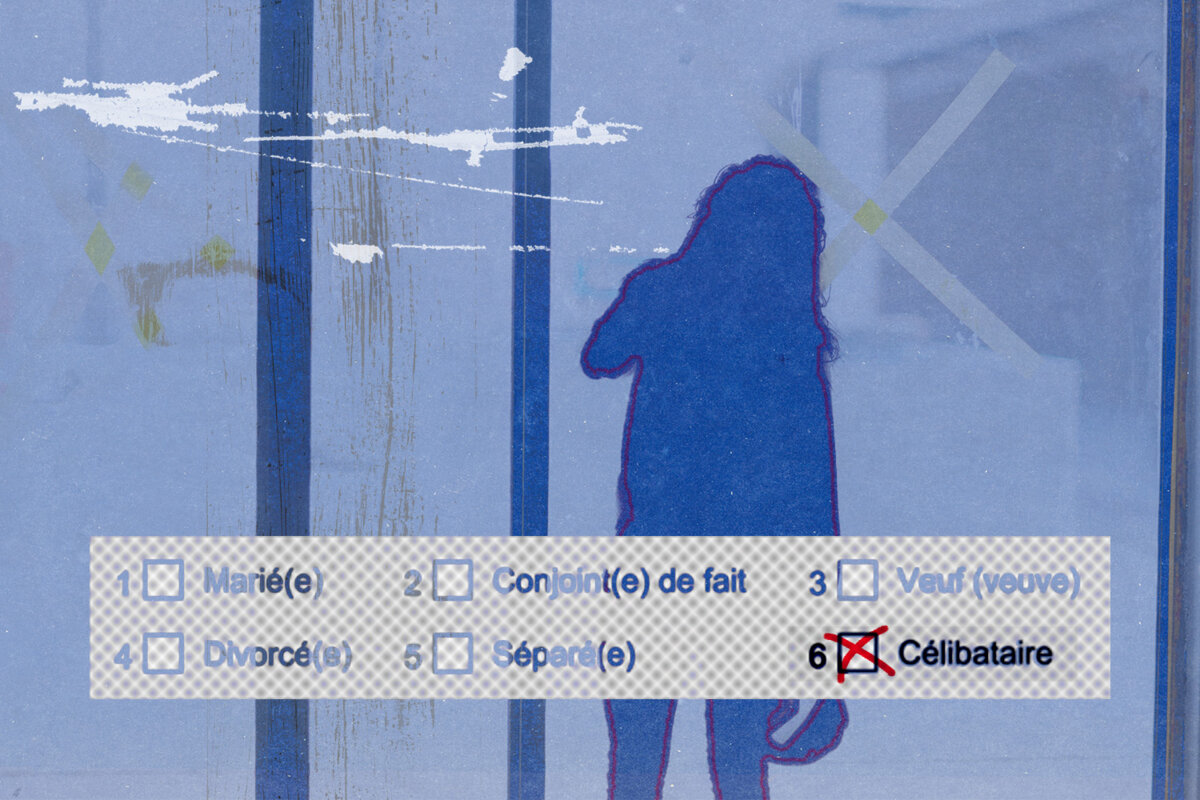

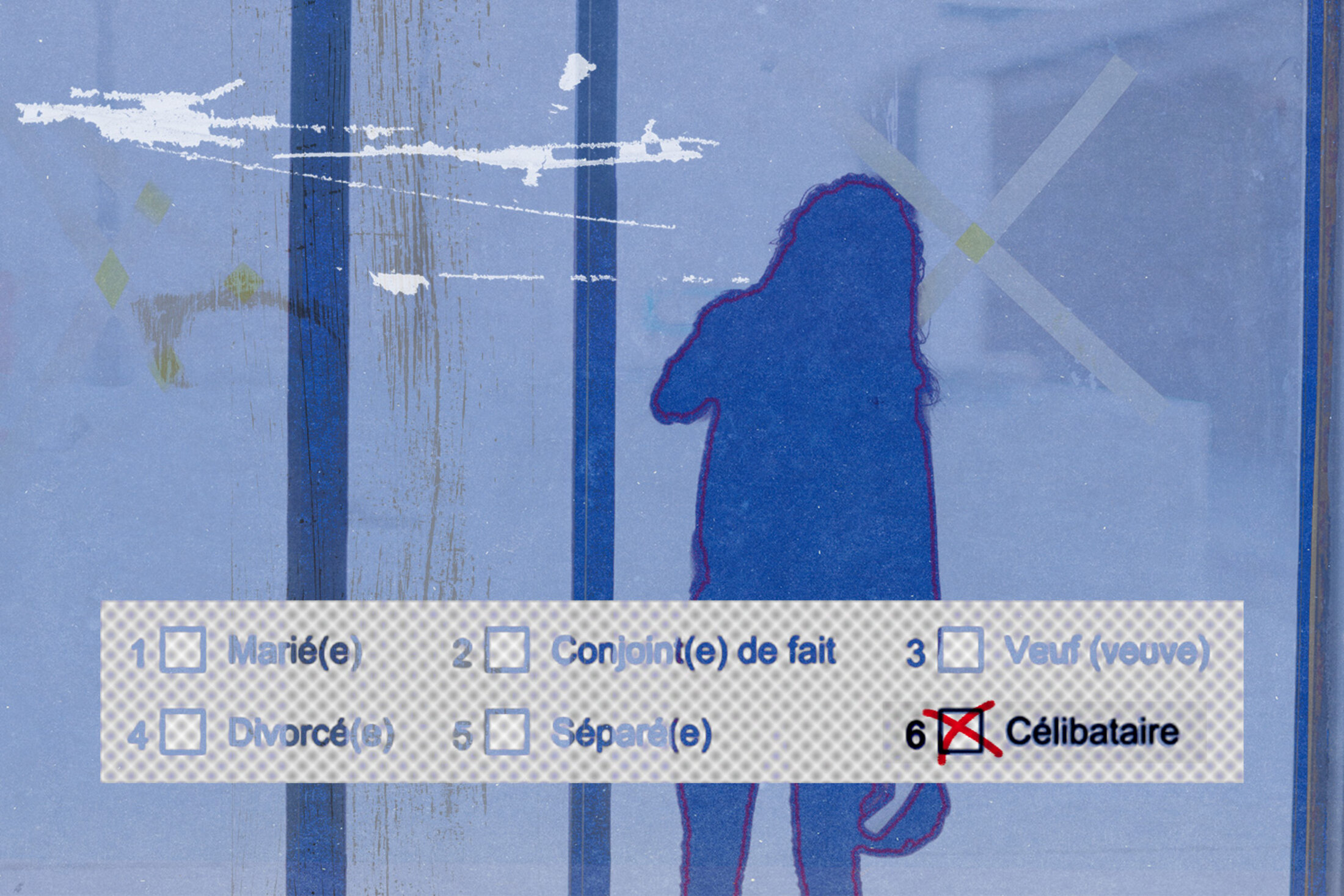

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Sociologist Charlotte Debest has just written a book on childless women, Elles vont finir seules avec leurs chats ('They'll end up alone with their cats'), published by La Meute. For her, the government’s proposal to exclude people without children from the Christmas bonus shows that such households are “easy targets who do not need to give presents and cannot complain since they already benefit from this or that social support”. In other words, it is as if there is a pecking order involving “deserving families” - those who have had children - and the rest.

She also notes that the family creates social bonds and ties individuals to a system of traditional, sometimes reactionary, values. The family tends to “put people back in their place in every sense of the term, in their social place and their gender role”. Having children is seen as the norm.

Source of poverty for women

Rachida Dati and Jean-Pierre Farandou are not the first politicians to take up this issue. At the highest level of the state, someone else has already sounded the alarm over falling birth rates in France: Emmanuel Macron. Two years ago, the president - himself childless - announced a “plan against infertility” in the name of “demographic rearmament”. The warlike vocabulary linked to his pro-natalist project sparked outrage on the Left and among groups supporting women’s rights and autonomy.

“The birth rate has always been used as a figure to assess a country’s growth, its future and its power, serving arguments that are by turns religious, military or economic,” notes Bettina Zourli, a popular writer specialising in issues of gender and motherhood. “As early as 1870, people were already saying that France had lost to Prussia [editor's note, in the Franco-Prussian war] because it hadn't had enough babies!”

Lucile Quillet, journalist and author of Les Méritantes ('The Worthy'), published by Les Liens qui Libèrent, also sees in this a “strong injunction” to women, implying that a “woman's worth depends either on their relationship or on their ability to have children, who will then finance social solidarity, pensions and growth”.

She points out that, for women, motherhood represents a double penalty. “They know it will cost them dearly in the long run and increase their economic dependence within the couple, which is a place of impoverishment for women,” Lucile Quillet says. “They do the domestic work, which allows men to get richer by advancing their careers, for instance.” This imbalance is made worse by failing public services, as shown by the lack of investment in nurseries and the devaluation of careers involving early childhood.

Percentage of childless women unchanged for 100 years

But what do the figures actually show? Bettina Zourli points out that, contrary to popular belief, the percentage of French women who “remain childless at the end of their fertile lives”, estimated between 10 and 15%, has remained stable for a century. What has fallen, however, is the number of children per household, leading to a lower birth rate and feeding alarmist conservative voices who lump everything together.

Thus 2024 saw a flurry of books published by reactionary women writers, such as Naître ou le néant ('Birth or Nothingness') by Marianne Durano and L’Enfant est l’avenir de l’homme ('The Child is Mankind's future') by Aziliz Le Corre-Durget, published by Albin Michel, portrayed as a “mother’s response to the ‘No Kids’ movement”.

Former minister Sarah El Haïry, appointed high commissioner for childhood at the start of the year, has also made it her priority to fight “against the ‘No Kids’ trend”. Speaking on France Inter public radio station on June 5th 2025, she claimed that this trend had “exploded abroad” and was “starting to take hold in France”, while conceding just seconds later that the phenomenon was “not particularly strong, that’s true”.

Not having children is seen as failing in life in our liberal societies.

The existence of such a “movement” in France needs to be seen in perspective, notes Bettina Zourli. Even though recent studies about people's intentions suggest a possible decline in the desire for children among French women under 35, it is impossible to speak of a “societal shift worthy of being called a movement”, given that “this generation has not yet reached menopause” and so the figures cannot be compiled.

In the collective work Nullipares, et alors? ('Childless, so what?') published by Éditions Points on November 7th 2025, she also points out that many childless women do not seek to politicise their choice and often feel at a loss when asked to justify their situation.

For sociologist Charlotte Debest, childless women “make up a statistical minority” but are increasingly being turned into a scapegoat in public debate, while there is no male equivalent figure. “It also shows how threatened the system feels by childless women and so it utters this rebuke. It says: ‘You’ll end up alone with your cat’, as if warning them about being unhappy,” she notes. For the sociologist, this “threat of social exclusion” means that “not having children is seen as a failure in our liberal societies, whose motto is fulfilment at every level”.

Shadow of the far-right

On July 28th 2025, Sarah El Haïry was interviewed again, this time by the newspaper Le Figaro. “The demographic issue is one of sovereignty,” she declared. At the end of the interview, the conservative paper appeared to raise the following issue: “Faced with falling birth rates, should immigration be encouraged?” The high commissioner for childhood dodged the issue. “To ask that question is to admit that we're not capable of meeting the birth rate challenge,” she said.

The far-right makes no secret of its desire to boost the birth rate. As Mediapart has already shown in 2024, “French fertility” forms part of its political project in a bid to hold back both immigration and the 'creolization' of society. “If we don't revive our birth rate, our people will disappear,” declared Bénédicte Auzanot, an MP for the far-right Rassemblement national (RN) party, in 2022.

More recently, in the summer of 2025, Pierre-Édouard Stérin - the billionaire who has placed his fortune at the service of the far-right - said that his “priority area for action in France today” was to have “more babies of European stock”. His plan is clear: to target single people and the childless.

“For those listening, who are young, get married! Marry young, and have as many babies as you can!” he urged. “If you're already married or engaged, help your single friends find someone, so they can be a couple. Spread a positive image of the family, it will encourage many others to start families tomorrow.”

Pierre-Édouard Stérin also supports the opening of independent Catholic schools with programmes rooted in “traditional” conservative values. Bettina Zourli sees this as a “underhand” way of imposing “social projects” on the population. She says: “It's not imposed on the French by law, but it is a form of shaping minds,” she says.

The calls for motherhood made in France from time to time may sometimes seem rather laughable in their excessive nature. But examples from abroad do give cause for concern. In Russia, the subject is taken very seriously, especially in the context of demographic decline. A year ago, the Russian Parliament passed a law banning “propaganda promoting a childless way of life”. Offenders in that country face fines equivalent to several thousand euros.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter