Abercrombie & Fitch (A&F), the fashionable clothes store chain that vaunts itself as a retailer for “cool” people, is back in hot water over its uniformly good-looking staff.

After several successful lawsuits filed against it in the US over the past decade citing discriminatory practices in its recruitment of staff, the retailer is now the target of an investigation, launched in late July by the French commission for the defence of citizens’ rights, for the same behaviour at its two stores in France.

The company claims it recruits models for its stores, which the rights watchdog suspects is simply a smokescreen explanation to hide the hiring as sales staff of only those who meet its stereotype of good-looking young men and women, which amounts to illegal discrimination under French law.

Since 2004, the company has been convicted for discrimination in its recruitment process in several in cases judged in the US , and which resulted in the plaintiffs being awarded significant sums in damages. In an interview with salon.com in 2006, A&F’s CEO Michael Jeffries openly confirmed the company’s policy of hiring “good-looking people” and its targeting of “cool, good-looking” customers.

Jeffries was asked how important sex and sexual attraction are in what he calls the “emotional experience” he creates for his customers. He replied: “It’s almost everything. That’s why we hire good-looking people in our stores. Because good-looking people attract other good-looking people, and we want to market to cool, good-looking people. We don’t market to anyone other than that.”

In May 2013 the company removed from its stores articles of women’s clothing that were sized XL and XXL.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

But the case of A&F is simply one small illustration of a far wider problem that is curiously hidden under a taboo of silence. A number of statistical and sociological studies in France and elsewhere demonstrate that people are regularly discriminated against by potential employers on the basis of their physical appearance. Too fat or too thin, too big or too small, or just plain ugly, a person’s bodily appearance can, and regularly does, cost them dearly in terms of professional opportunities.

Since a law introduced in 2001 , discrimination at the workplace for reasons of physical appearance is a punishable offence in France, but the number of cases brought before the courts is negligible. Most of these have concerned problems such as a chef who wore earrings , a fireman who sported a beard and pony tail or an employee of an electronics firm who turned up to work one hot day in a pair of shorts. Hardly any have concerned a person’s bodily appearance.

Accoring to Sandra Bouchon, a jurist for the French rights watchdog headed by ombudsman Dominique Baudis, the Défenseur des droits, the A&F case is a legal first in France.

Just 1.4% of all complaints lodged with the rights watchdog in 2012 concerned discrimination for reasons of physical appearance, and there are similarly very few recorded in previous years. In 2006, the French equal opportunities and anti-discrimination commission (which has since been merged with the human rights watchdog), pronounced judgments in two cases concerning the recruitment of receptionists It found that the candidates had unlawfully been asked to supply details of their height and other body measurements whereas an employer is only entitled to ask questions relating directly to the proposed post and for the evaluation of professional competence. In both cases however, the public prosecutor’s office took no action.

Since then, an article adopted into French labour law makes clear that “the prohibition of discrimination does not prevent a difference of treatment when it corresponds to a professional and deciding requirement, as long as the aim is legitimate and the requirement is proportionate.”

Sandra Bouchon argues that this would not allow for the discriminating procedure applied to the two candidates for the job of receptionist described above. But no list exists in law as to which jobs allow for a selection based on physical appearance. While one can imagine this is the case for a fashion model, can it be applied for a television presenter? Just how far can “legitimate” selection be stretched, beyond for example excluding a candidate whose physical size would prevent them from fulfilling their tasks, such as an airline steward who is too large to walk up the aisle, or too small to close the overhead baggage stores.

But such cases remain an exception. Jean-François Amadieu is the director of the French Observatory of discrimination, an academic research institution that studies recruitment discrimination in all its forms, and a professor of sociology with the University of Paris. “It is clear that the [Parisian cabaret venue] Crazy Horse has the right to hire girls with a particular kind of profile, in the same way that a legal precedent allows a Chinese restaurant owner to want only Asian staff in order to reassure his clients,” he says. “But for a post as a store assistant or a receptionist? A company [might] explain that its turnover will rise if it hires a pretty receptionist or a pretty waitress, but in this case the same argument could be applied for old folk or black people. One must be coherent. Beauty is not a skill, no more than the colour of skin.”

'Fat people keep quiet'

France is one of the very few countries to have incorporated into its anti-discrimination laws the question of physical appearance. The criterion appears in no international regulations, and among all developed countries only Belgium has included into its anti-discrimination law the notion of discrimination because of physical characteristics that are innate or caused by factors that are independent of the will of an individual, such as birth marks, burn marks, surgical scars or the effects of mutilation.

For Jean-François Amadieu, the reason for the small number of lawsuits for discrimination over physical appearance is that potential plaintiffs are unaware of their legal rights, and also the possibility of proving their case by a method of testing employers’ reactions to dummy CVs, a tactic employed by Amadieu and other researchers including his colleague Hélène Garner-Moyer. This involves sending quasi-identical CVs accompanied by different photos. “We compare lots of faces with or without an excess of fat,” Amadieu explains. “In the cases of jobs that do not involve exposure to the public, the faces with excess fat receive 30% less of favourable responses. And they have up to three times less of a chance to be called to an interview for jobs that involve exposure to the public.”

“Obese people represent about 15% [of the population] in France. Then there are all the other ‘unsightly’. This therefore involves a massive discrimination but about which little is said, into which very few researchers work, especially if we compare it for example with discrimination regarding sexual orientation which concerns a lot less people. Just where are the associations for ugly people? Who defends the cause of the ugly? Which lobbying group makes it an issue on the public agenda?”

Jean-Pierre Poulain, a sociology professor with Toulouse University and author of ‘The sociology of obesity’ (Sociologie de l’obésité), reports that of a group of 600 obese people he questioned as part of his research, 138 (23%) complained of being discriminated against at least once during a recruitment process. Another 204 (34%) said they had suffered discrimination at least once during their professional careers.

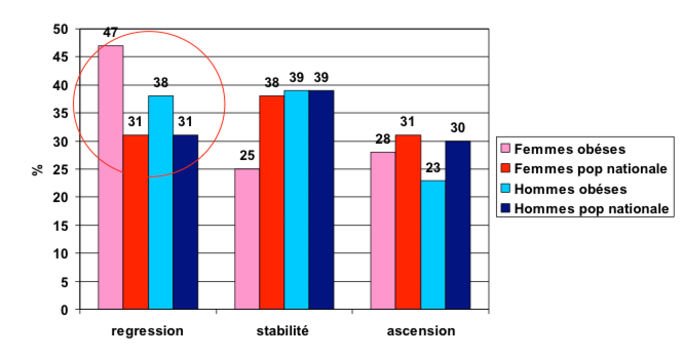

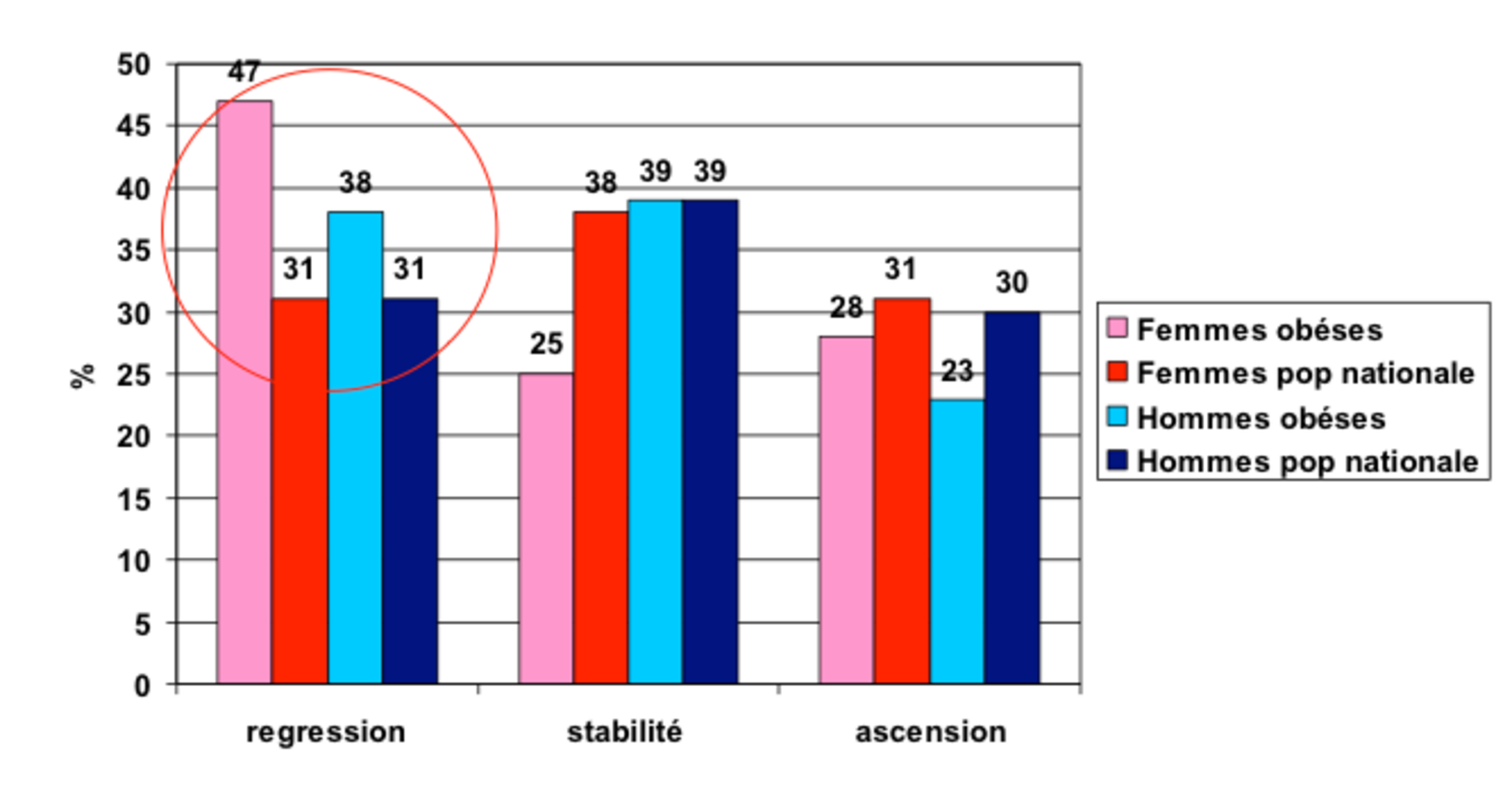

During his research, Poulain studied data from a French health ministry report on a national health and nutrition programme. He looked at the incidence of obesity on social advancement through dividing the population into three categories: those who had advanced in social status in comparison to their parents, those who were in the same status (stable) and those who had dropped in status. In all three categories, obese people were in a less favourable position in comparison to the national average. More specifically, the figures showed that concerning the group who had fallen in social status in comparison to their parents, while the national average for women was 31% this rose to 47% for obese women (see chart below).

Enlargement : Illustration 2

“Fat people keep quiet,” says Poulain. “It’s the effect of stigmatization, a particular form of discrimination that transforms victims into the guilty. It’s bricked over and associations don’t adopt a radical, demanding stance.”

“A moral judgment is made about the fat person. They don’t control themselves, they can’t be trusted. This judgment is linked to the supposed reasons of the corpulence. I’ve spoken to human resources staff who told me ‘if he eats too much it means that he doesn’t know how to control himself in his personal life, so can I really trust him in his professional life?’ On this point, women are clearly more discriminated against than men. I hear from many women managers whose fear is that they’ll put on weight. Not just because they want to be attractive, but because they worry that they’ll lose professional credibility. They apprehend the moral judgment.”

Despite the grim picture, Poulain says there has been progress. “In the middle of the 1970s, the restaurant chain Hippopotamus started recruiting only models. It was part of their concept and nobody had anything to say about it – perhaps also because it was a period of full employment. Today, that couldn’t happen again.”

Other, less obvious discrimination exists concerning small people. In a 2003 study, Nicolas Herpin, a sociologist with the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies, INSEE, found that a majority of small people were less academically qualified than the rest of the population and had a greater incidence of academic difficulties (notably repeating one or more class years). Herpin reported that while they were not more likely to be unemployed, or less likely to be recruited than the wider population, “they don’t enjoy the same professional advancement”, and that “they are given fewer positions of responsibility in the private sector”.

Herpin is also the author of a book entitled “The power of the big: the influence of the height of men on their social status”, in which he cites a 2004 study by two American researchers. In their paper ‘The Effect of Physical Height on Workplace Success and Income', Tim Judge and Daniel Cable report on their studies in the US and Britain, where they found that every for inch (2.54 cms) that a man is taller, he will on average earn 789 dollars per year more. More tellingly, they give the example that a man whose height is six feet (1.82 metres) will earn a yearly 5,525 dollars on average more than another who measures just five feet and four inches (1.65 metres).

Judge and Cable also found that those men who reached full height after the age of 16 were less likely to benefit from the income difference, while those who reached full height before the age of 16 were on average the biggest earners. Put more simply, those who were at or near full height by the age of 16 are better paid than the others, whatever their adult size. Because people are rarely, if ever, recruited according to their size when they were 16, there can only be speculation about the reasons for their greater professional success.

In 2011, a privately-financed French social aid association, Ereel, which funds a variety of projects across the country, launched a programme in partnership with the state employment agency, Pôle Emploi, to help job-seekers with their physical presentation, from hair styling to clothes. The association’s chairwoman, Christine Salaün, says the ongoing project has proved an impressive success: “Of the 900 people who have been accompanied over the past four years, 70% have found a job, even if things have become complicated over the last six months.”

“Physical [appearance] is a part of the mental [approach],” she adds. “We teach the ungainly to apply make-up, we re-do their hair, we beef up their moral. It’s not because a man has one tooth out of two missing that he shouldn’t believe in his chances.” Except, of course, in getting hired by Abercrombie & Fitch.

Meanwhile, the issue of discrimination over bodily appearance is not all a one-way problem. A study by two Israeli researchers published in June, entitled ‘Are Good-Looking People More Employable?’ found that female employers were susceptible to rejecting pretty women candidates for reasons of physical jealousy. In a quite staggering legal case brought in the US state of Iowa, a dentist’s assistant who was fired for being too attractive lost her lawsuit for unfair dismissal. Melissa Nelson, 33, was fired by her dentist employer on the grounds (and reportedly at the insistence of his wife) that she represented a threat to his marriage because of his temptation to have an affair with her. After an Ohio district court found in the dentist’s favour, Nelson took the case to the Iowa Supreme Court – where, last month, she again lost.

-------------------------

English version by Graham Tearse