Rosa's deeply-lined hands meticulously turn the pages of a spiral-bound notebook. Here, in neat handwriting, she has recorded a lifetime of domestic work. “There you are, I noted it down here: 7.15 euros net an hour. That was my salary as a housekeeper at the end of 2017 after thirty years of work. They declared me [editor's note, to the authorities] but they also paid me quite a lot of hours on the black,” the diminutive 63-year-old told Mediapart*.

The “they” refers to a very wealthy family* who have been based in the Nord département or county of northern France since the 19th century. The family was involved in cotton mills before becoming a key player in the region's textile industry. Its leading figure, Édouard M., was the very image of a local paternalistic boss. In the 1970s he presided over wool factories at Tourcoing, north of the major city of Lille, as well as in South Africa and the United States. Since that period the group has diversified but M's son and grandson still run cutting-edge textile firms in the département.

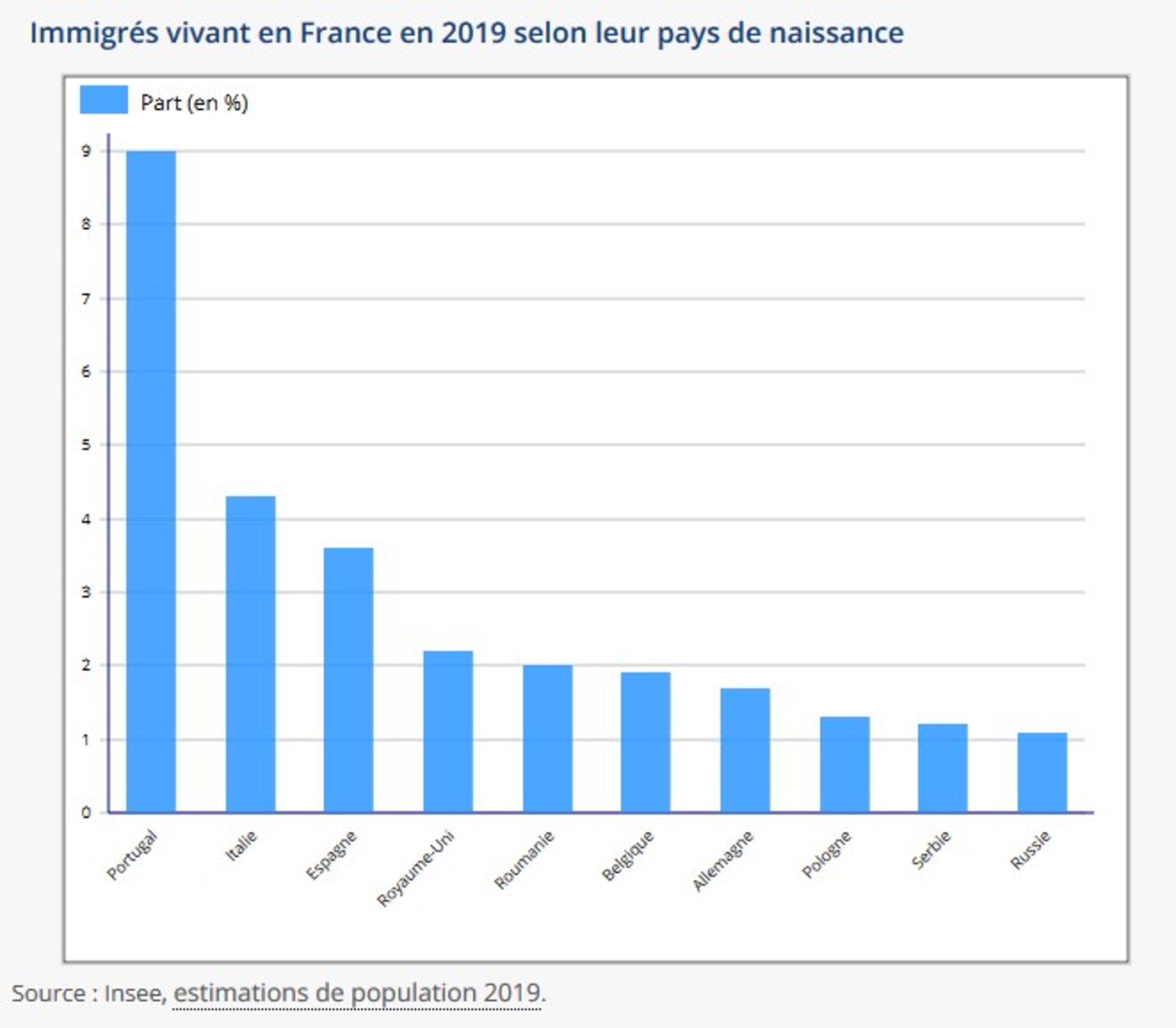

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Rosa – like all the housekeepers we have spoken to, we have not used her real name - lives in one of the narrow brick houses which are typical of the working class areas of Tourcoing and nearby Roubaix. Sitting in a living room dominated by imitation leather she describes her life up to the point where she became a housekeeper with the M. family.

“I come from Covilhã, a textile town in Portugal,” she said. “I came to France in April 1968 at the age of 11. My father had secretly crossed the border on foot a year earlier. He worked as a manual worker at Tiberghien, an enormous cotton mill in Tourcoing.” At the age of 18 Rosa herself became a worker at the Lainière de Roubaix textile factory, then at the Desurmont factory.

At the start of the 20th century the Roubaix-Tourcoing area was known as the 'French Manchester' and was the second largest textile region in the world after Manchester and south Lancashire in north-west England. More than 110,000 workers were employed in the sector. The factory owners in the Nord département avoided the sector's successive crises by moving into postal sales – setting up mail order groups such as La Redoute and Les 3 Suisses – and by importing cheap immigrant labour from Portugal and North Africa. But by the start of the 1980s the process of de-industrialisation began to decimate the region and Roubaix endured mass unemployment.

“The Desurmont factory closed. My mother was already a servant for an upper class family in the Nord,” said Rosa. “I had an aunt who was Édouard M.'s domestic servant. One of his children needed a housekeeper. They took me on in 1986 and I worked two years on the black before they gave me a contract to come and live at the property,” she said.

Overnight, the former factory worker swapped a rundown area of Roubaix for Marcq-en-Barœul, an upmarket suburb of Lille.

“The contract was unfair but I really needed money. For example, it stipulated that every other year I wasn't allowed to go away on holiday; I had to spend my four weeks of holiday at the property,” said the former employee.

The estate owned by the M. family is huge; it boasts a manor house, other large homes, a swimming pool, stables, a small farm and fields. In this it was like a number of other properties in the area, for Marcq-en-Barœul has one of the country's highest concentration of residents required to pay France's property wealth tax.

Yet barely six miles away lies Roubaix, ranked as one of the poorest towns in France. Here some 45% of the population live under the poverty threshold.

Marcq-en-Barœul and the neighbouring small towns of Bondues, Mouvaux and Wasquehal – a triangle that some dub 'BMW' – are brimful of properties with bucolic names such as La Cerisaie ('cherry orchard') La Prairie ('meadow') and La Hêtraie ('beech wood'). This is where the Nord's well-heeled bourgeois families reside in complete discretion. But hiding behind the the impeccably-trimmed cypress hedges which surround the properties lurks a form of domestic hell.

“I did everything; the cleaning, the washing, the ironing, the meals,” said Rosa. “And that doesn't take into account the fact that I also helped bring up their four children for which I was paid on the black: in the evenings I sometimes had to come back at 7pm just to give one of the little ones a bath.”

During the three decades that the Portuguese housekeeper worked for the M. family, she always had to observe the strict etiquette of class distinction; she was not allowed to use the same toilets as the family, to drink their mineral water or to sit in one of their chairs to rest.

“One day their daughter, who was barely seven at the time, became agitated when I was dealing with her. I asked her to calm down and she told me: 'You're the servant, you must obey me',” recalled Rosa sadly. Her own children were not allowed to mix with the children of the owners at the property. “[Those children] stated that I wasn't to play with them, because their parents had told them that I was poor,” one of Rosa's two sons confirmed.

“Every other Saturday, each Christmas and virtually every bank holiday I had to serve up the food for their family receptions,” said Rosa. “They made me wear a black skirt with a little white pinafore. I hated that, I felt ridiculous.”

Rosa's working conditions during these dinners were terrible. She had neither the time to eat herself nor permission to keep for herself anything of what she had spent the day cooking. “It was physically and emotionally gruelling. My back was in bits from having to serve each guest individually with very heavy dishes, for hours on end. At the same time I'd get stressed because the meals dragged on; as I had got them to agree to pay me more after midnight, they made me clean everything before the fateful hour,” she said.

A permanent source of tension between her and her employers was Rosa's holidays and time she took off for medical or family reasons.

Rosa was forced to defend her most basic rights in the face of her employers' guilt-inducing comments. “My boss couldn't bear me taking four weeks of holiday,” she said. “Each time I came back to work she asked ironically: 'So, did you have fun?' Was a week enough for you to relax?' After one of my rare times off sick I had the impertinence to talk about holiday dates. She replied: 'Don't even think about it, you've barely come back from holiday!'”

When, in 2005, Rosa dared to ask permission to leave the house when her youngest son was taken urgently to hospital after being attacked, she was told: “You can't just leave like that, you have to finish the bathroom first.”

Domestic exploitation

Immigration from Portugal to France started to grow at the end of the 1960s. Between 1969 and 1971 alone some 350,000 Portuguese settled in France.

“At the time the strategy of Portuguese immigrants was to make a maximum amount of money quickly; they became members of the proletariat in France to be able to escape this status when they got back to their country,” said Victor Pereira, a lecturer in history at the University of Pau in south-west France and a specialist in Portuguese emigration. “But the plan changed over time: children were born, they were sent to school here and returning to Portugal became more difficult after the fall of the dictatorship in 1974, as the Portuguese authorities focussed more on repatriating the retornados, the Portuguese based in the former African colonies.”

The academic added: “For the Portuguese in Roubaix-Tourcoing, it's difficult to distinguish between economic and political immigration. Many of them come from the Covilhã region, in the centre of the country, which was a textile industry area disturbed by workers' strikes and repressed by the fascist dictatorship of [António de Oliveira] Salazar. On top of this there was the Portuguese colonial war: many young men emigrated to France to escape military service which forced them to fight for four years in Angola, Mozambique or Guinea-Bissau.”

Like Rosa, Sandra, aged 75, comes from the centre of Portugal and immigrated to the Nord département in 1968. She was a seamstress in a textile factory but was made redundant after it closed in 1986. She then became a housekeeper at Mouvaux, next to Tourcoing and Roubaix, for two wealthy families: the V. family and the T. family.

The V. family's group is a major one in the local textile industry and during the 1960s it owned around thirty factories in Roubaix and Tourcoing. This powerful family had many different political and economic branches. As for the T. family, they were closely associated with the development of the textile industry in the Nord. In the 19th century they founded a prestigious bank which supported the wealthy entrepreneurs in the region.

As she dug lettuce from her vegetable plot Sandra told Mediapart: “I've honestly never seen people like that.” For more than thirty years she cleaned, scrubbed, vacuumed, ironed and cooked for these two wealthy capitalist families from the Nord. But in terms of workers' rights, it was one long struggle. “I worked a lot for them on the black and I never had an employment contract,” explained Sandra. Like Rosa, she had to be entirely at their disposal, especially for family gatherings. “Each Sunday evening I was exhausted and dying of hunger: I wasn't allowed to eat from the dishes. I had to eat in secret,” she said.

The housekeeper was kept under tight supervision. At the start of the 2000s, after the V. family had returned after travelling for a month, they accused her of having started work late one day. “I was terrified because I had indeed started my morning half an hour late. I was at the doctor's surgery and there was a long waiting list … I later learnt that they had got an neighbour to keep an eye on me. They did that after twenty years of service!” she said angrily.

When her husband died in 2013 Sandra, by then aged 68, was still working for the V. and T. families. She was absent from work for a week because of the funeral arrangements and funeral, but when she came back the families showed little sympathy; the seven days she had been away were simply deducted from her payslip.

Finally, after two decades of devoted domestic work and hard saving, Sandra managed to buy her own little house. This was greeted reproachfully by her employers, and despite her long service her pay was never increased again. “They kept on saying to me: 'You've bought a damn property thanks to France's money!' What really killed me was that they didn't stop going on about how we Portuguese were good workers, very honest, tidy and conscientious, but they couldn't accept that we have the same rights as them,” she said.

Sandra then burst into tears as she described another incident. “Twenty years ago I had to take my granddaughter to the V.'s home because her mother was away. It was just for a few hours. I put her in the playroom and she was sitting there well-behaved on a little chair when my boss's mother shouted at her as if she was a dog: 'Sit on the ground immediately!'” Sandra concluded: “I was proud to introduce my seven-year-old granddaughter to her but it was a terrible humiliation.”

When working for her family Rosa was endlessly compared with people from North Africa, who were seen as less servile and less honest than the Portuguese. “They kept going on about how we were Catholic like the French, that we had the same culture and that we were a brave people,” recalled Rosa. During the annual major maintenance work at the property she had to let black or North African workers in by the back door. “My niece, who usually replaced me during my holidays, was no longer called on by the M. family after 2018 after they learnt that her daughter was seeing an Arab,” she said.

After Algeria became independent from France in 1962, the government in Paris feared the country would be submerged by a wave of North African immigration. In April 1964, and under pressure from employers who were already keen on cheap Portuguese labour, the prime minister Georges Pompidou allowed Portuguese people without documentation to enter freely into France. “To legitimise the racism towards the Algerians the French authorities at the time came up with a narrative about how the Portuguese were good and not very demanding workers, and that they also represented the latest European immigration (after the Italians and Spanish) and so could be assimilated,” said Victor Pereira. “It was absurd because no one knew the Portuguese and they still don't know them today.”

Enlargement : Illustration 5

The academic said that the stereotypes ascribed to the Portuguese housekeepers - about their innate servility and being trustworthy workers – are social constructs that emerged after many trials and humiliations. “For example, many tried to trap their household employees by hiding banknotes under the sofa,” said Victor Pereira. “There was reputational capital to be built up with their employer so that other households could benefit afterwards,” he said, pointing to often heard expressions from wealthy families such as “You can trust my Maria”. Rosa and Sandra confirmed that such devious stratagems were used; both say that in their early days they used to find money left carelessly under the beds or in shirts to be ironed.

“The Portuguese have gone through a process of racialisation in France in parallel with Algerian immigration. Some basic stereotypes have been attached to them, such as the fact that they are naturally 'docile', 'hard-working' and that they are 'brave people' with limited ambitions who integrate very well,” said Margot Delon, head of research for the CNRS research centre at the Centre Nantais de Sociologie in west France. “They have a superior status to that of the more predominant colonial and post-colonial migrants but inferior to that of 'Whites'. The Portuguese thus represent an intermediate category, what we describe in the social sciences as 'honorary whites'.”

The sociologist said that this “empty whiteness” results in a large proportion of Portuguese women occupying segregated and servile posts in the jobs market, such as domestic staff or concierges. “Their employers recreate physical and social borders inside some households,” said Margot Delon, referring to the experiences of Rosa and Sandra. “Once they no longer have use of them, they rapidly lose their usefulness and they are discarded.”

Enforced resignation

The Portuguese public television station is pumping out the latest summer pop song hit from the living room. Ana, her arms folded, remains unmoved as she stands under the glass ceiling of her kitchen. “My father was hired by the Tiberghien factories in Tourcoing,” said the 65-year-old. “It was a sad landscape, full of chimneys, what a shock compared with Covilhã! Then all the cotton mills went bust. I was pregnant with my first boy and I easily found some small household work. The Portuguese already had a good reputation.”

Having worked on the black for a couple of renowned industrialists, Ana went to work for family D. in 1991. The family had set up a flourishing company which today boasts clients such as nuclear firm Areva, oil group Total and luxury goods company Louis Vuitton.

Ana worked hard for their family, who have a manor house in the north of Lille complete with swimming pool, sauna and tennis court. She was paid via the universal service employment voucher (CESU) which is often used for domestic workers, and she never had an employment contract. “I never managed to do all the housework as their property was gigantic, a real labyrinth of stairs,” she said. “It was terribly disordered, they always threw their clothes on the floor and then I had to look after their three children, to whom I was very attached.”

The D. family had a passion for large pedigree dogs such as St Bernards and Alsatians. “They had five of them. It was horrible because I spent whole mornings cleaning up their excrement, their urine, their mud stains throughout the house,” said Ana. “They often fought amongst themselves. Then one day came the accident.”

That was one morning in March 2015 when the housekeeper arrived at the property and suddenly found herself being attacked by one of the dogs. “It wanted to bite another dog it wasn't getting on with. My whole hand was torn to shreds in its mouth. There was blood everywhere, you could see my bone,” said Ana. She was patched up at the accident and emergency unit at the hospital where she needed 20 stitches. But the serious wound became infected. Ana was signed off work by a doctor, who renewed her sick leave each month while specialists helped her recover the use of her hand.

“During this period my boss hassled me to know when I was coming back to work,” she said. “My doctor told me that given my state of health it was quite simply impossible. She [editor's note, her boss] put me under such pressure that as soon as my telephone started ringing my whole body started to tremble. In November I gave in. I was afraid to lose my job and I went back.”

Her return to work became a nightmare, however. Though the D. family usually got a specialist company company in once a year to clean the manor house's windows, her employer demanded that Ana, now aged 60, carry out this dangerous work, despite her bad hand.

“She was no longer the same person. She wanted to push me to the limit so that I'd resign my position: as I was five years from retiring and also the victim of a workplace accident they were going to have to pay me higher compensation. Yet they are so rich it was nothing for them,” she added.

After three days of domestic chores at the manor house her doctor insisted that Ana no longer went back. Terrified by the D. family, she took a mediator with her to ensure that her employers signed the documents that stated she was unfit for work because of a workplace accident. As she wrote a cheque in final settlement, Ana's boss told her: “I didn't expect this from you.” That same year the family's business turned over more than 100 million euros.

“We are getting more and more calls from Portuguese women who have worked as housekeepers, concierges or caretakers,” said Eloy Fernandez, a volunteer at the section of the CGT trade union dealing with workers in the domestic services industry, the Salariés des Services à la Personne (SAP). “They have worked there for quite a long time and the employers have realised they are going to have to pay what they see as large payments when they retire. So they do all they can to get rid of them. That's usually by bullying them through unpleasant remarks, overworking them or giving them degrading tasks to do.”

Enlargement : Illustration 7

In 2015 Rosa started to suffer from chronic lung illness and then contracted a serious case of hepatitis in the summer of 2016. From that point the atmosphere in the M. household got worse. Exhausted, and close to retirement, the housekeeper was subjected to daily pressure and humiliations in order to make her quit her job. At the start of 2017 Rosa asked her employer to buy a new floor squeegee. The next day she found a simple cloth with a handwritten note next to it. It read: “To clean the floors on your knees.” She said: “I was going to work with fear in my stomach, wondering what was going to happen to me. The worst thing was that I felt guilty because they said to me: 'We're really counting on you' and 'don't let us down'.”

Rosa added: “They didn't want to sack me or wait for my retirement, so they wouldn't have to pay me compensation. That's their method: bully you into leaving on your own account. That's what happened to my predecessor as well as my aunt who worked her fingers to the bone for Édouard M.” In 2017 her stubbornness finally led to her being sacked. It was a year before her retirement.

So, after 30 years of exploitation, Rosa left with 7,482.59 euros, a figure which included her pay-off, as a final settlement. She received not one word of thanks nor a leaving present. “I opened the envelope containing the cheque and I cried with anger,” she said. “They didn't even round the amount up, saying they were complying with the strict legal minimum. Making reference to the Employment Code when they regularly paid me on the black, you couldn't make it up!”

Worn-out bodies and broken spirits

Stéphane Fustec, who works at the CGT-SAP trade union branch, said: “We've recently been dealing with cases of Portuguese women who have been worn down, and become isolated professionally, who have sometimes spent forty years as a domestic worker and who forgo their rights out of the personal ties they have with their employer. The collective agreement covering employers who are private individuals is hugely modified from the Employment Code; it really is the minimum service.”

In 2017 Sandra badly broke her upper arm in a fall at her home. She suggested that her daughter-in-law replaced her at the V. and T. family homes while she recovered. When she came back to work she was told that after her accident she would not be able to work as well as before. So she was offered just two days work a month to clean the silverware and do the ironing.

“My daughter-in-law was young and doing heavier jobs such as cleaning the ceilings, so why bother with an old woman over 70?” Sandra said. “I didn't accept their offer. Though I'd been there 30 years I myself decided to quit, without any pay-off. I wanted to keep my dignity.”

Today her daughter-in-law still works as a domestic for the V. and T. families. As she has no other job or a driving licence, her husband drives her each day from the small town of Orchies, a round trip of around 44 miles a day, to earn a poverty wage.

Enlargement : Illustration 9

To see the impact of their work you just have to look at the housekeepers' laboured walk, their sloping shoulders and worn hands. Rosa, Ana and Sandra have had their bodies broken by their labours. “I've lost more than 50% of my breathing capacity because of disinfectant, caustic soda and the aerosols I had to use every day,” said Rosa.

Ana suffers from algodystrophy, also known as complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), in which a person experiences persistent severe and debilitating pain. All three of the women Mediapart spoke to complain of a bad back because of repetitive domestic chores such as carrying shopping and baskets of heavy washing up and down the stairs, and bending over to scrub bathrooms.

“The housekeepers reach retirement in a very damaged state physically. The latest statistics from the Ministry of Employment show that among workers in the domestic services sector the rate of workplace accidents and professional illnesses is growing three times more than the average,” said Stephane Fustec of the CGT-SAP. “Domestic employees do not have to have a medical check during their careers. Moreover, domestic work can lead to a lot of accidents, because of the repetitive actions and the variety of tasks to be done.”

As well as the physical damage there are also the psychological scars left by being abruptly shown the door after years of service by employers with whom one has developed very strong ties. “I regularly have nightmares: I'm always there, at the D.'s home, doing the housework,” said Ana.

She has been seeing a psychologist for five years to treat heavy depression. Rosa herself has only just recovered from depression after the mental ordeal of her last two years at work. “I was crying all the time. I was afraid of no longer being able to make ends meet; that all had an impact on my relationship with my family and friends,” said Rosa.

“Because of all those years of being underpaid and working on the black I am now on a pension of less than 900 euros a month with a top-up [pension], though I started working at 16,” said Ana. Her husband was recently signed off work because of a slipped disc, after 40 years of textile factory work and temporary jobs.

Sandra and Rosa are both widows and live alone and also each receive a modest pension of around 800 euros a month. In order to get by both are still forced to do a few hours of domestic work, still for illustrious bourgeois families in the Nord département … and still on the black.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter