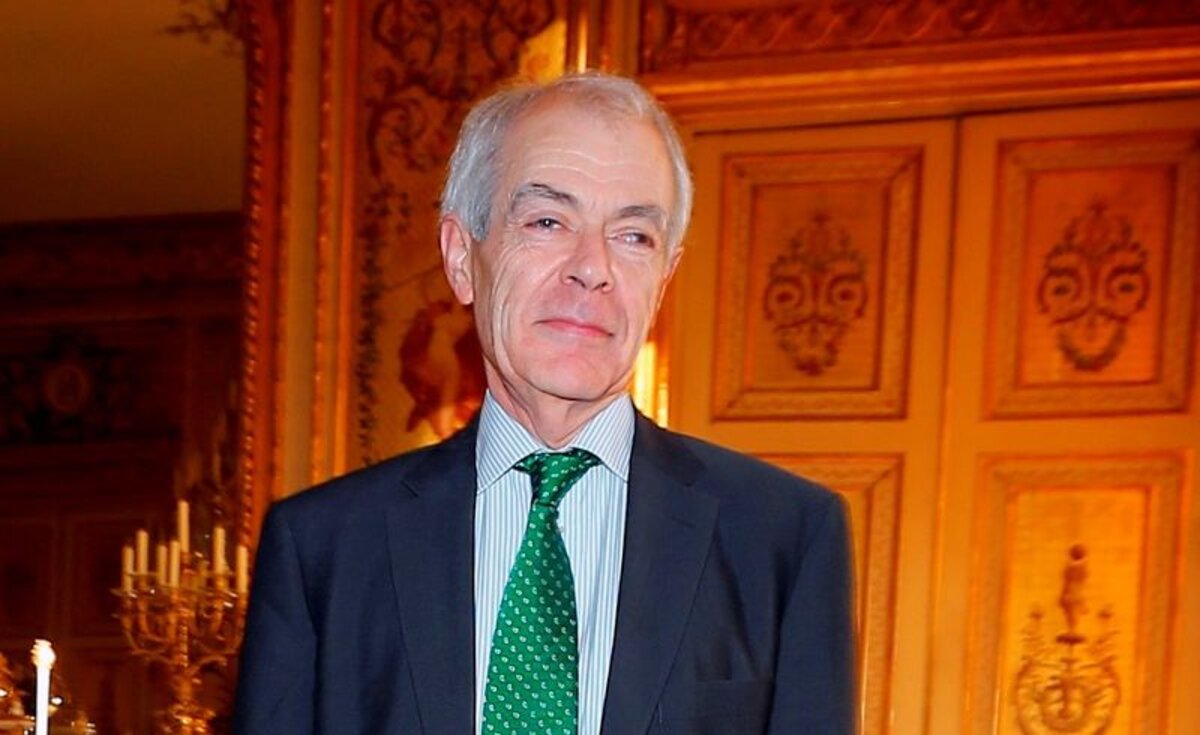

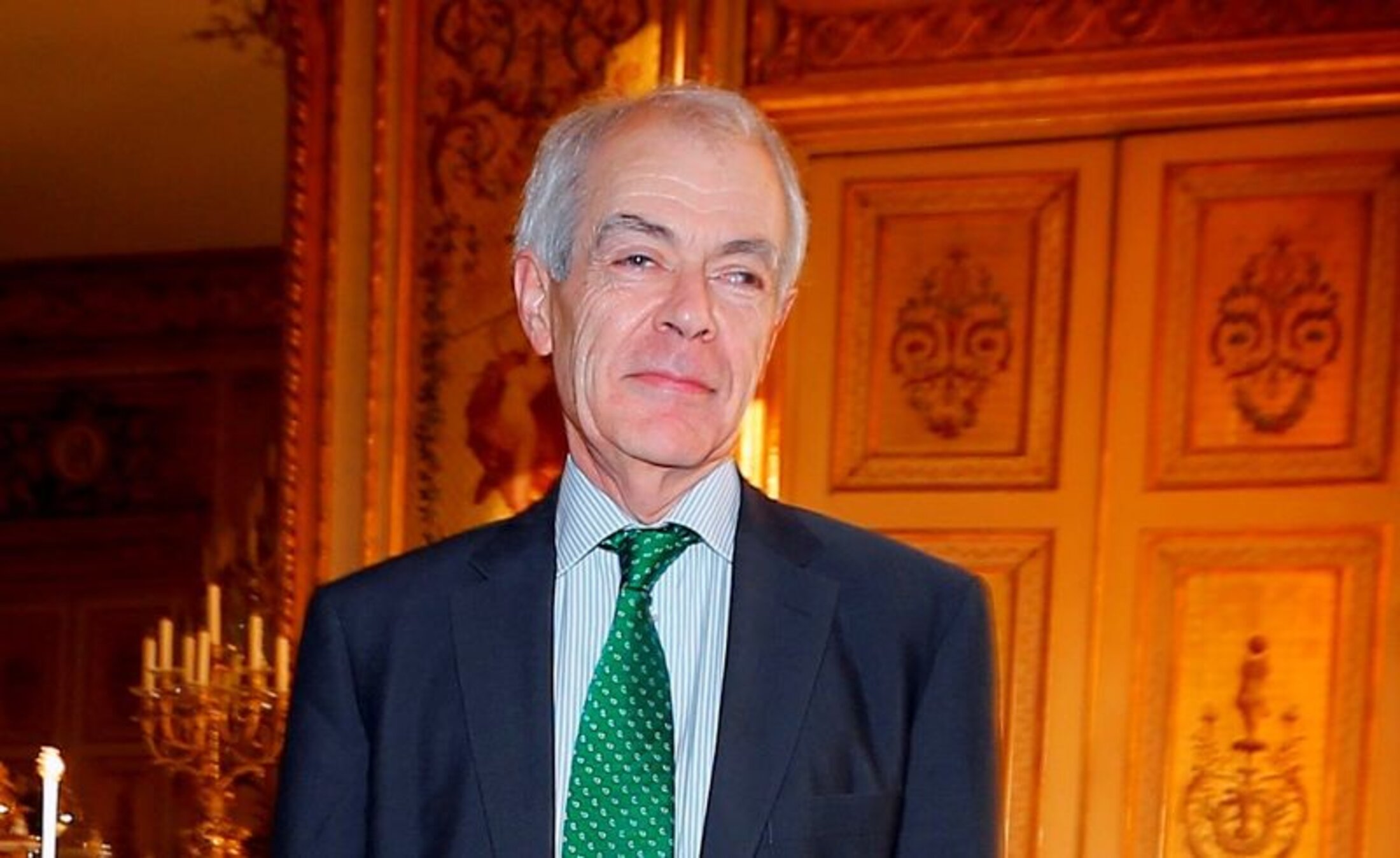

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Jean-Marie Delarue was General Inspector of Places of Deprivation of Liberty, (Contrôleur général des lieux de privation de liberté, or CGLPL) from 2008 until July 2014, effectively acting as a controller of, and ombudsman for, prisons, during which time he led numerous campaigns for the improvement and reform of carceral conditions. Previously, he sat for six years on the commission monitoring the conditions of preventive detention. Delarue is a member of the French Council of State, an advisory body to the French government on legal matters, notably lawmaking, and was last year appointed as president of the French national commission for the control of communications interceptions by security services.

-------------------------

Mediapart: According to the French justice ministry, of all those people imprisoned for criminal acts related to Islamic extremism only 16% have previously served a jail sentence. Is prison a place that privileges the spread of Islamic extremism or is it just one place among others?

Jean-Marie Delarue: The phenomenon of radicalisation in prison should not be overlooked, but it should not be overestimated either. Sociologically, people who become radicalised come more often than others from disadvantaged backgrounds. They therefore run a greater risk of being imprisoned. The path taken by Amedy Coulibaly [Editor’s note: the Paris gunman responsible during the January 7th- 9th attack for the murder of a policewoman and the executions of four hostages in a Jewish supermarket] is an example. But, originally, the seeds of radicalisation are found in the [sink] housing estates, among the networks that set up around mosques. Some religious places are held by very radical imams, as everyone knows, and certain sermons are listened to more than others. The Adda’wa mosque in the 19th arrondissement of Paris was, in this respect, a particularly noted meeting place.

Prison is therefore, for sociological reasons, a place of radicalisation, but it is neither the only one, nor the most important. If one compared the population of radicalized people who have been jailed with the radicalized population in general, one would certainly find a prevalence [of the former], but not an overwhelming one.

Mediapart: Currently, less than 160 people are serving time in French prisons for crimes related to Islamist extremism. Among them, 60 are considered to be proselytes. Are they subject to specific treatment?

J-M.D.: Proselytism in prison is a known phenomenon and has been dealt with by prison staff for about ten years - in any case, overt proselytism, which manifests itself by a vigorous faith, including to the detriment of other prisoners. It is demonstrated by the desire to wear religious garments elsewhere than in the cell, and to gather in an visible manner outside of designated situations. In face of this visible behaviour, the penitentiary system has reacted. It has forbidden collective demonstrations during exercise. The qamis [traditional Muslim male robe]is accepted, but [only] inside cells. Inmates who rebel against the general regulations are transferred. These measures are tried and tested and efficacious. Few difficulties were made known to me when I was controller [of prisons].

What is new comes with the development of a radicalisation that operates in a discreet manner. This phenomenon is, by definition, difficult to measure and to counter because it does not show itself. But it is identifiable because prisoners complain about it. During my mandate, I received lots of complaints from people who were prevented, in the name of religion, from taking showers in the naked, or whose cellmates forced them to imitate their lifestyles, even if they didn’t share the same faith or the same practices. Some non-Muslims were made to conform to the precepts of the Koranic religion against their will. Some cohabitation was revealed to be violent.

Because that goes on inside the cells, the guards pay less attention, even showing complete disinterest. Prisoners considered to be radical are currently not especially contained in individual cells. That is explained by the lack of space, because of the overpopulation of prisons, and by the fact that these people, sentenced to short prison terms for petty delinquency or a distant involvement in terrorist projects, are held in maisons d’arrêt [a category of prison in France dedicated to those placed in preventive detention or short-term jail sentences of less than a year] which are even more densely occupied than penitentiary establishments. These tensions between prisoners seem to me more significant and preoccupying than proselytism as such.

Mediapart: What is your opinion about the proposition by French Prime Minister Manuel Valls that the most extreme Islamists should be placed together in prison quarters apart from the other prisoners? Also, how can they be identified?

J-M.D.: The placing of prisoners, which is the responsibility of the heads of establishments, is the most difficult operation that exists. Certainly, one avoids placing a Kurd and a Turk, a Serb and a Croat, in the same cell. But the overpopulation in prisons limits the possible combinations. To separate Islamic radicals from others will add to the complexity. And how will these people be identified? How can one distinguish someone with radical opinions from another?

To separate those who have been sentenced for terrorist acts in connection with radical Islam is possible. But then another question is raised. What do you do with radical Islamists who are serving preventive detention? Can they be separated when they have not been convicted? What’s more, many [Islamic] radicals are in prison, as in the case of Amedy Coulibaly, for acts that have nothing to do with radical Islam. The danger is to find in the ‘Islamist quarter’ people convicted of that but who have evolved, whereas excluded from it are prisoners professing a radical Islam but who were arrested for other reasons. ‘Islamist quarters’ would at best allow for a diminishing of proselytism, but certainly not to put an end to it.

Finally, has the administration an interest in grouping together people who resemble each other in their opinions? This question is close to that raised about Corsican and Basque terrorists. The Basque terrorists have never been grouped together, and complain about it. Corsican terrorists were grouped together in [the Corsican town of] Bastia. The result is edifying. Very unordinary things go on in that prison [in Bastia], the prisoners occupying a place which is, at the least, problematic in the management of the prison. The danger is that relations with the guards become distanced and that the quarters acquire a prejudicial autonomy.

If they are amongst themselves, the risk is that the prisoners more easily flout regulations, even if they are locked in their cell 24 hours per day, or if they are allowed out [of them] two by two, like in Fresnes [prison, close to Paris]. What do you do if they go hunger strike or lead a mutiny? The danger is to transform them into martyrs. I fear that the grouping together of people reputed to be dangerous would produce a ‘boiling pot’ effect.

Mediapart: What do you propose?

J-M.D.: The more we try to ascertain opinions, the more people will dissimulate them. Consequently, for me, the dissemination is the best solution. About 200 people in France are concerned by the issue, for an almost identical number of prisons. So that the guards have control of them, it would be better that they be placed in ones or twos, at the most, per establishment. As soon as there are more than four or five, management becomes complicated. In truth, there is no good solution. The real solution is to try to convert these radical people to other religious practices, with imams for examples.

Mediapart: Imams have been talked about for years. Why is this issue still undecided? Can radicalisation stem in part from discrimination that Muslims say they experience as believers in prison?

J-M.D.: Muslim prisoners do indeed very often complain of being discriminated against for being Muslim. There exist racist reactions by guards. It takes the form of insults, punishment of all sorts. The hierarchy must be particularly vigilant about the behaviour of the personnel. Some requests by prisoners, and which don’t complicate prison management, should be granted. I’m thinking notably about food. Some Muslims go hungry because they put meat aside.

Yet the meals are prepared by private firms, who propose prisoners with all possible and imaginable diets. About 15 diets coexist in total, without iodine, without fish, and so on, according to medical prescriptions. It is not difficult to prepare ‘religious’ meals. That would not only concern Muslims. I checked on this, it would not cost more, it would even potentially be cheaper, and it would in no way be a breach of secularism, as long as it does not get in the way of the proper functioning of public services. There must not be the creation of solidarity between Muslim radicals and others over living conditions that are experienced as punishments.

As for imams, the question depends both on the state and the religious institutions. Budgets are not sufficient. They must be increased to improve their remuneration. But it must also be recognised that it is not easy to find people trained for this type of role. Improving general living conditions in prisons is a necessity. Not doing so pushes prisoners into becoming radicalised.

Mediapart: One of your major propositions when you were controller of prisons was to provide easier access for prisoners to the internet and phones. Given the context, does that still seem to you a pertinent idea?

J-M.D.: I stick by that. Prison policies must not depend upon the behaviour of a few rapists, murderers or terrorists. The immense majority of prisoners are not [like Paris serial killer] Guy Georges. They are sentenced to short prison terms for petty delinquency. The link with family is primordial. The more they have contact with their entourage, the less they run the risk of repeat offending. Concerning the Islamists, one could consider that this [proposed] measure would make it easier to monitor them.

-------------------------

The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse