Over the past eight months France has been locked in a fiercely divisive and often violent debate over the government’s same-sex marriage bill, which was finally enshrined into law last Saturday by President François Hollande.

The law, which legalizes both marriage and adoption rights for homosexual couples, has been hotly contested by a religious and political alliance led by the Catholic Church and associated organizations and right-wing opposition parties who staged a series of major protest demonstrations beginning last autumn.

The lengthy parliamentary and public debate on the issue has been marked by outspoken anti-gay views, which SOS Homophobie, an association set up to monitor and counter homophobia in France, has described as creating “a liberation and mediatisation of homophobic speech”, reporting a 27% year-on-year rise in homophobic incidents reported to it in 2012.

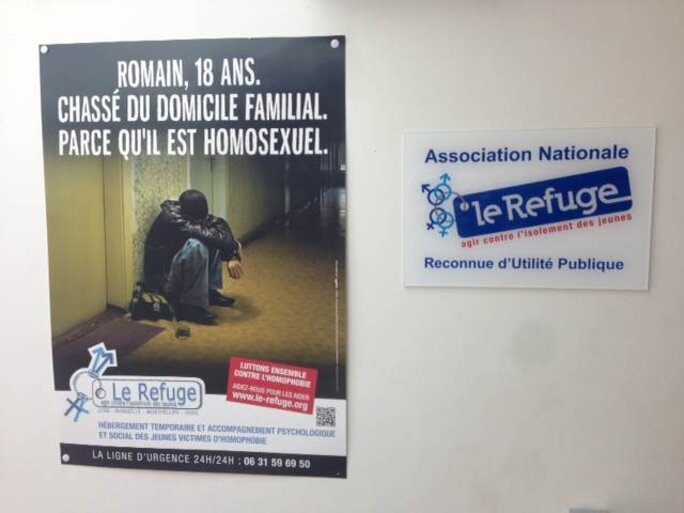

Le Refuge is a national association dedicated to helping young male and female adult victims of homophobia offers shelter, medical services and psychological counselling to youngsters who have been rejected by their families because of their homosexuality. This month it celebrated its first ten years of existence with a depressing observation: since the beginning of the debate over the same-sex marriage bill, Le Refuge has seen a surge in requests for help, reaching five times the number during the same period one year earlier, according to Frédéric Gal, the association’s director.

At the association’s centre in Paris, Gerdel, a 21 year-old arts undergraduate, is one of those who recently sought its urgent assistance. One month ago, he told his parents about his homosexuality for the first time. Almost overnight, they banished Gerdel from the family home situated in the Val-d’Oise département (county) just north of Paris. “The news coverage surrounding same-sex marriage, the desire to live my life, to no longer be afraid of the judgment by others, pushed me into telling them I was gay,” he explains.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Like so many other young gay men, Gerdel says the French parliament’s ratification of the same-sex marriage bill has come as “a relief” and opens a future “of living in the light”.

He recalls how his father, a former soldier who he describes as “normally introverted”, exploded with rage when he discovered his son’s homosexuality, telling him that “if you want to live that sort of life, the door is wide open”. Gerdel says his mother, an auxiliary nurse, said nothing. “They gave me 15 days to find to find a place to live,” he says. “For them, I took care of my appearance, dressed in fashionable clothes, but not gay. They are Protestant, so they think it’s not right. I thought it would take them a few weeks to accept. I wasn’t expecting such a violent reaction. I was shocked.”

Gerdel contacted le Refuge, which swiftly found him a place in one of its larger flat-share shelters in Choisy-le-Roi, a southern suburb of Paris. When he was offered the place, Gerdel says his mother told him simply that “it’s best like that”.

Since leaving home, Gerdel has had no further contact with his parents nor with his younger brothers and sisters who have also rejected him. Only his elder brother has remained loyal. “For him, there’s no problem, but he couldn’t let me live with him, [because] his girlfriend isn’t very gay-friendly.”

Le Refuge created its first centre in the city of Montpellier, southern France, in 2003, based on a similar project that was already established in the British city of Manchester. Today it has seven full-time staff, 110 volunteer workers and six centres around mainland France ((Paris, Lille, Lyon, Marseille, Toulouse and Narbonne) and another in the French Indian Ocean island La Réunion. Each year it provides lodgings for about 150 young homosexuals, and it has gained official recognition from the state as providing a public service.

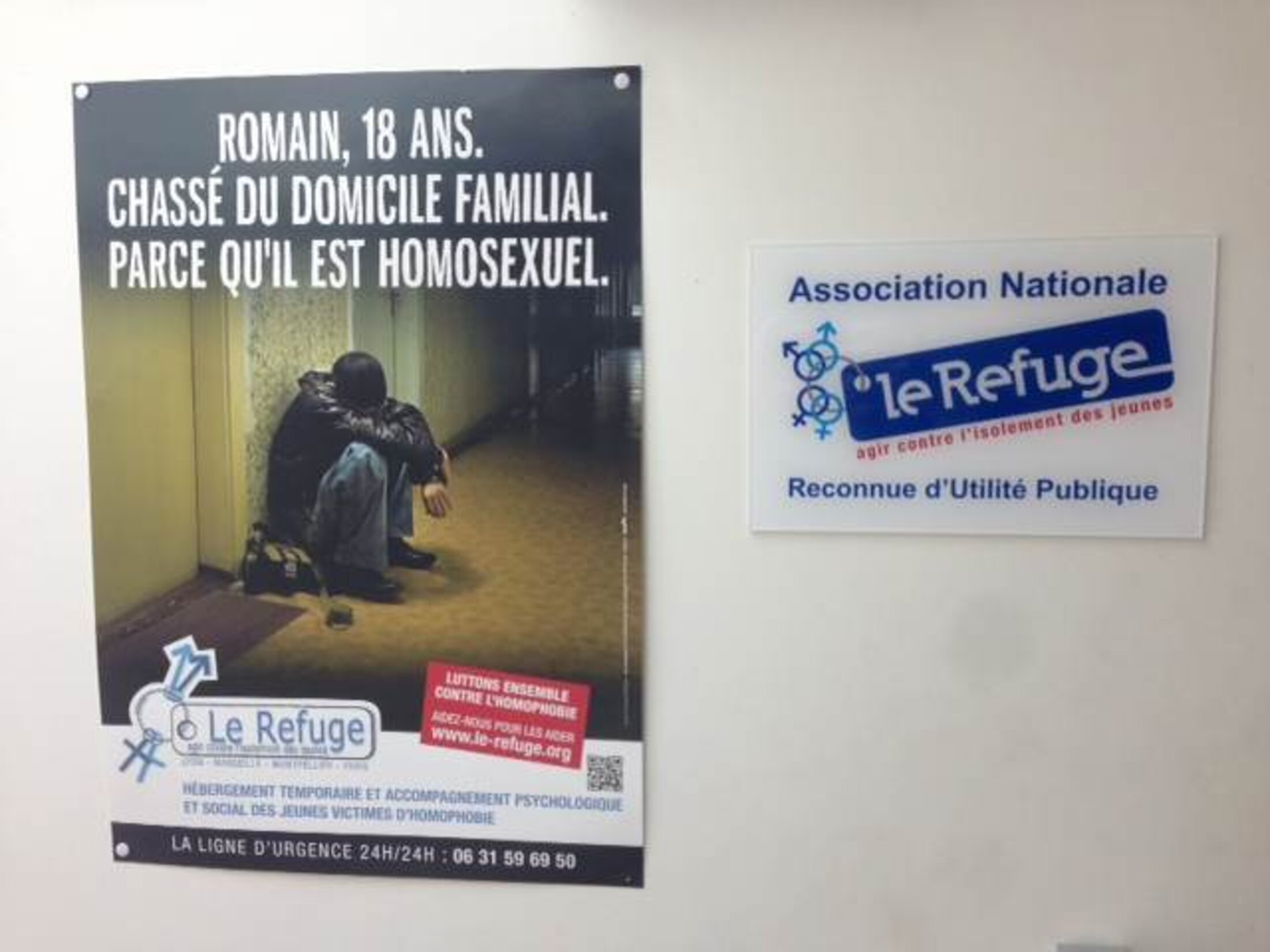

Enlargement : Illustration 2

“The initial reflection at the start was that LGBT [Lesbian, Gay, Bi-sexual and Transexual] militancy was very developed, but there was no structure in existence to help young LGBTs,” explains Johan Cavirot, who works on a voluntary basis as an administrator at the Paris centre of Le Refuge, situated rue d’Aligre in the 12th arrondissement. “Below the age of 18, the social services for children take charge of them, above 25 years’ old they have access to financial aid, such as the RSA [a minimum welfare benefit],” says Cavirot. “But for a young homeless person aged 18-25 there is not one euro from the State. And it is difficult for a youngster of that age to find themselves in a shelter with people who have been homeless since ten years.”

Nationally, Le Refuge receives 40% of its financing from local authorities, and the remaining 60% from private donations. But its resources are far from able to meet the demand for lodgings. “We receive 500 per year, with 41 lodgings at a national level,” says Cavirot. “We’re clearly under-sized.”

'Some are worse-off than me, out in the street'

Enlargement : Illustration 3

“All these youngsters are constantly insulted,” says Cavirot. “They switch on the TV and they hear [outspoken anti-gay marriage militant] Frigide Barjot, they go into the street and they see the opponents demonstrating against what they are. Within families, parents comment on the TV news programmes, they say what they think and they forget that they are potentially being heard by young gays going through the thick of a period of self-questioning. When a young boy of 15 hears his father, while watching the news, say that if he had a gay son he would kill him, that doesn’t give the youngster the will to talk about the subject.”

Gerdel says his parents “were for the demonstrators and wanted them to be even more violent”, although they did not join in the street protests.

“It’s the announcement which causes the rupture,” continues Cavirot. “It can lead to death threats.” Between September and November last year, the Refuge had eight emergency cases of newly-made homeless young homosexuals seeking shelter. One involved a young man from Normandy, who explained his father had tried to strangle him. “It’s a family in which everything ticked along, both parents have jobs, the children go to school,” recalls Cavirot. “His father is unnerved by sexual relations. He shouted ‘you’re an arsehole’ at his son, he’s stuck in a caricature of [the film] La Cage aux Folles.”

Cavirot says other cases involve young homosexuals whose parents, opponents of the same-sex marriage law, demanded that they join them on the protest marches against the bill, “forced to carry banners that attack what they are”. He cites the example of Adrien, a 17 year-old boy whose parents are unaware he is gay. He wrote to the Refuge in an email: “I don’t know if you can imagine how destroyed I feel by each homophobic demonstration, knowing they include the people I love and that each time they speak with nauseating words about a homo they are also talking about me.”

Cavirot says the association deals with cases from all kinds of backgrounds. “There’s no typical family situation,” he explains. “We have children of managers, of doctors, chemists, manual workers, immigrant families, families of all religions.” By far the majority – 80% - are young men. “Because a girl can hide it for longer, more easily and will announce it when she’s able to live by her own means,” continues Cavirot. “On the contrary, when a boy is going to come out, he sometimes wants to exacerbate the issue and be part of a caricature. It’s a sort of shell.”

The Paris centre of Le Refuge holds two weekly open-doors sessions when youngsters can meet together and talk with staff. Among those present on Saturday May 11th were some who are living in accommodation provided by the association, others who regularly come along to socialize. Sofiane, (whose real name is withheld upon his request), 21, still lives with his parents who are of North African origin. He hasn’t told them he is homosexual. His secret, he explains, was harder and harder to live with, and things came to a head in 2012 when he was preparing to sit his Baccalauréat school-leaving exam.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

“During my exam preparations I tried to give it my all but I wasn’t able to concentrate because of all that, my performance was stalling,” he recalls. His Spanish teacher noticed there was a problem and drew Sofiane into a discussion, and the youngster explained his homosexuality. The teacher gave him an autobiographical book (Un homo dans la cité) by a young gay who tells of his own distressful experience, in a Muslim household in a run-down housing estate, of stigmatization and bullying until the brave and liberating day when he finally decided to live his homosexuality openly and proudly. Sofiane then reluctantly told his aunt, who had also noticed his schooling difficulties.

The young man says he gets on well with his family, who live in Colombes, a western Paris suburb. His father works in a restaurant, while his mother raises his five sisters and brothers. But he says he cannot imagine declaring his homosexuality to them. “It would kill my mother, the poor thing,” he explains. “I am her eldest son. She’d ask herself ‘how are the others going to turn out to be?’ My father could ban me from being with my brothers and sisters, because he knows that is what would hurt me most.”

For several months he has heard his mother “throwing insults in Arab when the TV news spoke of the same-sex marriage bill”, while his father “embarrassed by the subject” stayed silent. He says during last year’s presidential election campaign he tried approaching, in a roundabout way, the subject of his gayness with his 18 year-old sister, with whom he is close. He told her his father had advised him to vote for François Hollande because of his manifesto policies regarding immigration, adding that he guessed his father hadn’t seen Hollande’s pledge to introduce same-sex marriage rights. But she didn’t take up the hint. “My sister has gay friends, but it’s like in every household, everything’s fine as long as it doesn’t directly concern the family.”

Sofiane contacted Le Refuge after watching a television programme about its work. “It’s a place where you can be yourself,” he says. “I see people who are like me, who aren’t going to judge me. I feel less isolated. And I realize that some are in situations worse than me, out in the street.” He says he isn’t very concerned about the demonstrations against gay marriage. “[the] Marriage [issue] is a good thing, but it won’t stop homophobia. The only thing I hope for is not to be attacked in the street.”

'We have only one desire - to one day close Le Refuge'

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Johan Cavirot underlines that this sentiment is typical of many. “These youngsters don’t ask for anything other than indifference,” he says. “One of them said it well the other day. ‘We just want to be, why the need to justify loving one or another person?’”

“They need to rebuild themselves,” he says. “Our vocation is to be a springboard and not to house them for 20 years. They stay for between one month and one year, the time to seek alternative solutions, to put together a file with which to request an accommodation, a job or a university grant.”

The centre’s director, Frédéric Gal, does not believe there has been a rise in homophobia as such but that “it’s just that it is more widely expressed during the [gay marriage] debate”, a view that is at odds with both SOS Homophobie's findings and the experiences of a number of gays interviewed during counter-demonstrations in favour of the bill. “But the ground of homophobia has always been a very fertile one,” he adds. “When people hear ‘dirty queer’ they don’t become offended. If they hear ‘dirty Black’ or ‘dirty Arab’ there’s an up-in-arms reaction.”

The Refuge is engaged in a number of projects within secondary schools to address the problem of homophobia. “Before dealing with homophobia and explaining that homosexuality is not paedophilia, not an illness, nor a choice, youngsters must be made to think about the relationships between men and women, and the place of women,” argues Gal.

“Often, a man must correspond to very precise criteria of virility, and for some if he is homosexual he does not meet these criteria, he’s necessarily going to want a sexual relationship with you, and so on. Lesbians don’t suffer this less, but it’s more invisible. For some, it [lesbianism] is less disconcerting, notably because there is a fantasy among some boys about being in the middle. But the day they understand there’s no place for them there’s violence.”

Bullying within schools was earlier this month the subject of a controversy in France surrounding the release of a video clip for a song by rock group Indochine called College Boy, in which a pupil is tortured by his classmates. Because of the violence of some of the scenes, France’s audiovisual watchdog, the CSA, moved to have it banned from TV screens. Le Refuge joined in support of the clip being shown, via a comment article by Gal published on website Rue89 . “This clip does nothing other than illustrate – albeit abominably – the sad reality that afflicts many youngsters helped by the association [Le Refuge],” he wrote.

So just what does Gal think the passing of the same-sex marriage law will change regarding homophobia in France? “It will change lots of things because it will make attitudes evolve and people will say ‘right, the law says that, we’ll get on with it’”, he answers. “It won’t prevent homophobic behaviour, including that of teachers and head-teachers who are against the law and who won’t find it a normal situation that two women or two men pick their children up from school. At Le Refuge, we are ink to a feather pen. We give tools to schools, but for things to advance teachers must provide a relay.” Which, he suggests, is far from easy: “Recently, we were involved in a project with a final year [secondary school] class. The teacher cut short the debate.”

Johan Cavirot believes that same-sex marriage law was badly presented by its political promoters. “It was approached from a point of view of sexuality, of homosexuality, whereas there should have been a focus on the celebration of the love of two people.” He sees an advancement in attitudes will come with the next, post same-sex marriage law generation of parents. “The children of today who will learn about equality at school will be the parents of tomorrow,” he says. “They will instill these values in their children.”

Le Refuge celebrated its tenth anniversary earlier this month with a week of meeting events held at its centres around France and which drew leading political figures and celebrities from the world of showbiz and sport. “But we have only one desire – to one day close Le Refuge,” comments Cavirot. “We’re a long way off. The more we become known, the more we are asked for help.”

-------------------------

English version by Graham Tearse