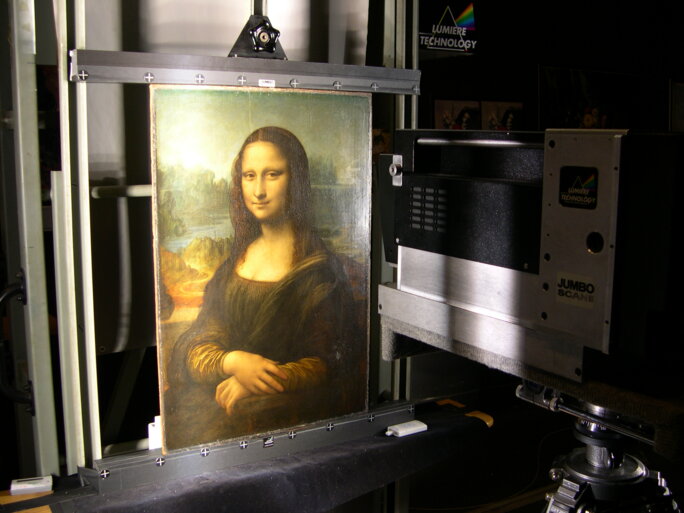

He is the first expert to dare challenge the Louvre. Pascal Cotte, a self-taught scientist, is the inventor of a revolutionary multispectral camera and discoverer of many secrets hidden in the works of Leonardo da Vinci. He has sent a final legal warning notice to the museum and the national research and restoration centre the Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France (C2RMF) over their alleged “parasitism” in relation to his work. In legal terms he is alleging that they have “copied something of economic value of another which is the result of expertise and intellectual work”.

It is the high-profile Leonardo da Vinci exhibition at the famous Paris museum, which comes to an end on February 24th, that is at the centre of the issue. The exhibition's catalogue, which focuses in particular on the progress made in imaging work on da Vinci's paintings, has not just chosen to ignore Pascal Cotte's ground-breaking discoveries. According to his lawyer, Sophie Viaris de Lesegno, the catalogue has also “hijacked and appropriated them without deigning to make any reference to his prior works”.

Those discoveries were published in a book that Cotte wrote in 2015 called 'Lumières sur Mona Lisa' (published in English as 'Lumière on The Mona Lisa: Hidden Portraits'). The scientist had taken care to present his finding to curators at the museum before publication. In October he published a second book 'Monna Lisa Dévoilée – Les Vrais Visages de la Joconde' ('Mona Lisa Unveiled – the true faces of La Gioconda'). But the data obtained by his multispectral camera, which were first published in 2008 and which have shed new light on Leonard da Vinci's painting techniques, have been ignored by the Louvre.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

“The Louvre denies hijacking and appropriating Mr Cotte's works,” the museum told Mediapart. But it cannot deny hiding them.

“The history of art is made up of hypotheses formulated by different specialists, using evidence from archives, from observing the works and from scientific imagery,” said the Louvre's statement. “These hypotheses can be contradictory. In this instance the curators of the 'Leonardo' exhibition don't agree with Mr Cotte's hypotheses. That's the reason why they don't cite them.”

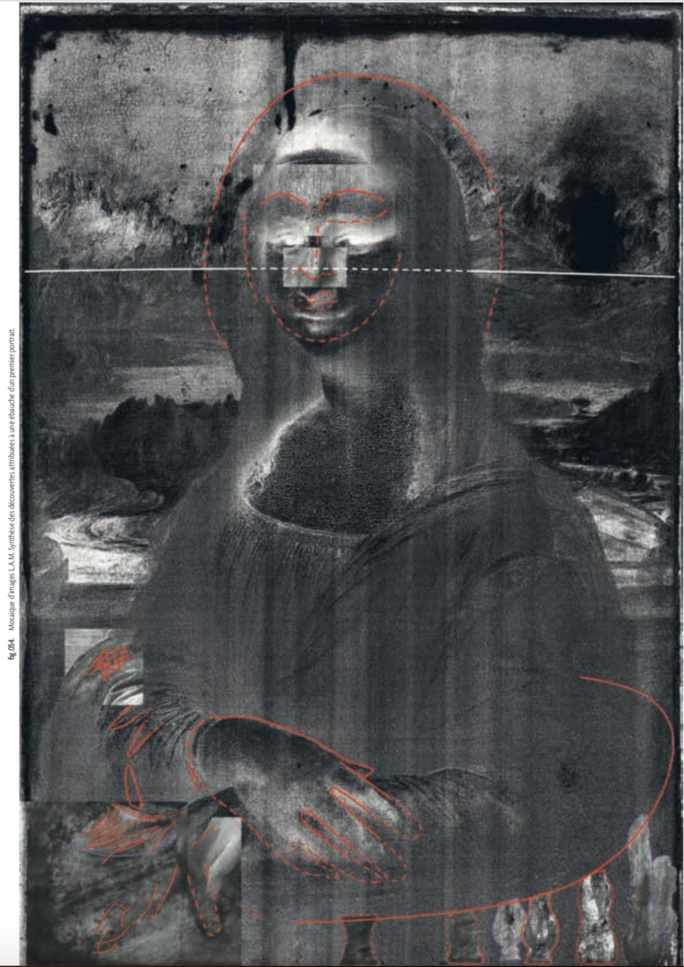

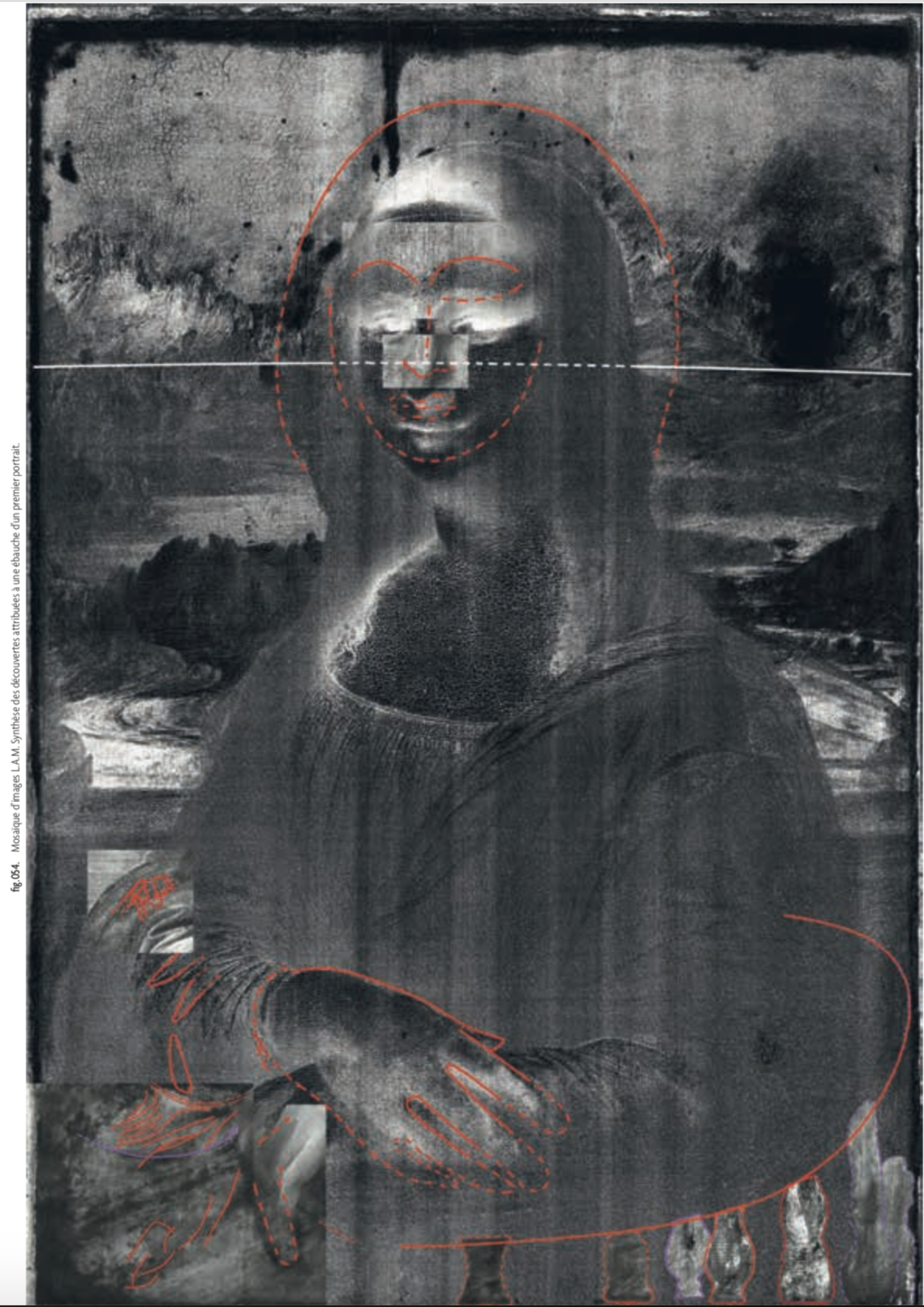

Yet while Pascal Cotte does have several theories, what he has produced more than anything else are images. The images he published in 2015 were unprecedented and revealed some hitherto unknown elements in the 'Mona Lisa': a different dress and hairstyle, and some sketches that had never been seen or referred to. Previously, in 2008, Cotte's images, which were used by a laboratory at the French research centre the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), revealed the secrets of Leonard da Vinci's sfumato painting technique, a technique which softens the transition between colours and gives the impression of a slight veil over the painting, as if blurred by smoke. The Louvre has not mentioned these images either.

“It's a delicate issue,” said Isabelle Pallot-Frossard, director at the C2RMF, who said she has passed the case on to the Ministry of Culture. “There was no plagiarism or any parasitism,” she said. “They are different works. The works which were published [editor's note, by the C2RMF and the Louvre] were done so on the basis of recent work.”

Pascal Cotte already had tricky relations with the Louvre back in 2006. Having digitised the Mona Lisa at the museum's request, the expert noticed that the Louvre then used his experimental findings in two works, Au Cœur de la Joconde and La Joconde, Essai Scientifique – 'La Joconde' is the usual French name for the Mona Lisa – without crediting him.

On that occasion he sought an injunction but the judge did not want to rule on the substance of the issue. Cotte insisted that his images of the Mona Lisa were protected by copyright. But the Louvre and the Ministry of Culture claimed that they were technical works and the issue was never settled.

Later, with the dispute behind them, the Louvre asked Cotte in 2008 to digitise the painting La Fuite en Égypte by Nicolas Poussin, and then in 2011 La Belle Ferronnière ('Portrait of an Unknown Woman') another work by da Vinci. He also wrote a chapter of the book La Fuite en Égypte which was co-written by Sylvain Laveissière, general curator in the paintings department at the Louvre.

Cotte has carried on with his scientific work up to the current day. He is a partner in a laboratory and has completed work on the discovery of the 'spolvero' or 'pouncing' technique – similar to tracing and using pierced paper to leave an outline – employed on the Mona Lisa. Cotte also recently successfully digitised some palimpsests or manuscript pages for the Centre Léon Robin which carries out research into ancient philosophy.

The project to digitise the Mona Lisa in October 2004 came out of the blue. “You have to come and digitise painting 779. I can't tell you more on the phone,” a manager at C2RMF told him. “I quickly discovered it was the Mona Lisa,” recalls Pascal Cotte. The Louvre wanted to obtain some colorimetry measurements – colour measurements – with Cotte's new multispectral camera, a prototype developed in association with the Crisatel European programme.

So Pascal Cotte spent 24 hours in the offices of the C2RMF, under the watchful eye of an official, and then handed over all copies of his files to a manager.

His camera is a jewel of modern technology. “It has the highest resolution in the world,” he says. It can capture 12,000 pixels; a motor then moves the capturing device over 20,000 vertical lines which allows it to employ 240 million pixels on each channel. Eight halogen lights synchronised with the capturing device light up each line for a fraction of a second. The camera has 13 colour filters in its bandwidth – 10 filters in the visible spectrum and three in the infrared spectrum. It therefore takes 240 million times 13 sets of measurements, or three billion in total.

“My camera measures the interaction between the light and the material,” said Cotte. “I make an image for each wavelength. My camera's light beam spreads out. It comes into contact with the glaze, and it goes into a layer of the painting. It encounters different pigments, some that reflect, others that absorb. You don't know in advance the nature of the paint layer that the light is going to encounter.”

The main aim of the process with the Mona Lisa was to obtain a “scientific measure of the work's colour”. And to get colorimetry measurements to help understand and anticipate its ageing process. But Cotte also obtained a basis for identifying the pigments and also some imagery data which showed up “some profound differences”.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Before he built this camera, Pascal Cotte, who created his own company Lumiere Technology, was involved in various projects. He developed a video data acquisition card and then digitalisation software for high-resolution photos for the press; he also came up with a scanner to digitise land registry plans, then studied colorimetry for a textile project, so he could then reassemble the colours according to the light.

During the same period Cotte was also developing a camera with a capture device designed by the company Thomson for the Spot-5 satellite and which already had lighting capabilities beyond the norm. This cutting edge technology was later incorporated into his new multispectral camera which he adapted for use on works of art.

Since 2008 the data Cotte that has obtained on the Mona Lisa has been used by the Institut des NanoSciences de Paris to understand the secret of Leonardo da Vinci's sfumato. A study by the researcher Mady Elias – cosigned by Cotte in the journal Applied Optics – revealed the presence in the Mona Lisa of a glazed area – the superimposition of layers of one type of pigment on the surface, an “umber”, an ochre containing a little manganese. Mady Elia said the data showed “the use of a glaze technique inspired by the Primitive Flemish painters [editor's note, the Early Netherlandish painters]”.

'I note that they carried out searches to find my discoveries'

The same study also determined the composition of the second layer of the painting as a “mixture of 1% of vermilion and 99% of lead white” - this was a technique used by Italian painters at that time – and in addition carried out a “virtual removal” of the glaze.

“The huge advantage of a multispectral camera is to simultaneously record 100,000,000 reflectance spectra on the whole painting in a short time,” Mady Elias wrote in her study. “These raw data ... allow us to provide a virtual unvarnishing of the painting to identify the pigments embedded in the superficial layers, and to calculate the trichromatic coordinates for each spectrum and thus for each location.”

This operation revealed “possible original colors as they were when Leonardo offered the painting to King François I. In particular the lapis lazuli identified in the sky has lost its green color due to the yellow old varnish and has recovered its blue hue. It is the same for the face that finds again its predominant pink hue,” added the study.

Meanwhile Pascal Cotte had digitised a second da Vinci work, Lady with an Ermine, at Kraków in Poland, in 2007. With the digital data obtained from this painting the scientist was able to develop new algorithms and discover three successive versions of the painting; a different dress is shown in the first version, an initial form of the ermine was found in a second version of the painting. It was in the final version of the work that Leonardo da Vinci made the animal larger and added lion's paws. These discoveries were unveiled in a 2012 book called 'Lumière sur La Dame à l'Hermine'.

Bolstered by these discoveries, Cotte went back over the data obtained five years earlier on the Mona Lisa itself. “And there I discovered some incredible things,” said Pascal Cotte. “The Florentine dress that was changed, an unfinished hairstyle design, and lots of other details that allowed you to identify the artist's trials and errors.”

In 2015 the expert got in touch with Vincent Pomarède, the former directer of the paintings department at the Louvre, who is today the museum's deputy general manager, to show him the new images extracted from his camera shots taken ten years earlier. “He was amazed and said to me 'I knew that there were other versions of the portrait below!'. He picked up his phone and got me a meeting the next day with Sébastien Allard [editor's note, the directer of the paintings department at the Louvre] and Vincent Delieuvin [editor's note, the curator in charge of 16th century Italian paintings]. The next day I presented my work to them but they remained silent from start to finish. I had also alerted the C2RMF.”

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Vincent Delieuvin, who coordinated the current Leonardo da Vinci exhibition to mark the 500th anniversary of the painter's death, did not get back in touch with Cotte.

Indeed, the catalogue of that exhibition in fact gives a summary of da Vinci's painting technique explored with the “use of X-ray fluorescence mapping developed by the C2RMF”, and does not refer to any other works. Managers at the research centre reveal, on page 362 of the catalogue, that “some modifications added during the course of [the painting's] execution can be identified”. They point to the appearance of a “light sketch underlying the face, in particular shadows around the nose, the eyelid and the right cheek” and highlight how da Vinci “started to dress Mona Lisa in a dress with a rounded neckline … The slashed sleeves with a different fabric are continued by pleated sleeves, according to a typically Florentine style”.

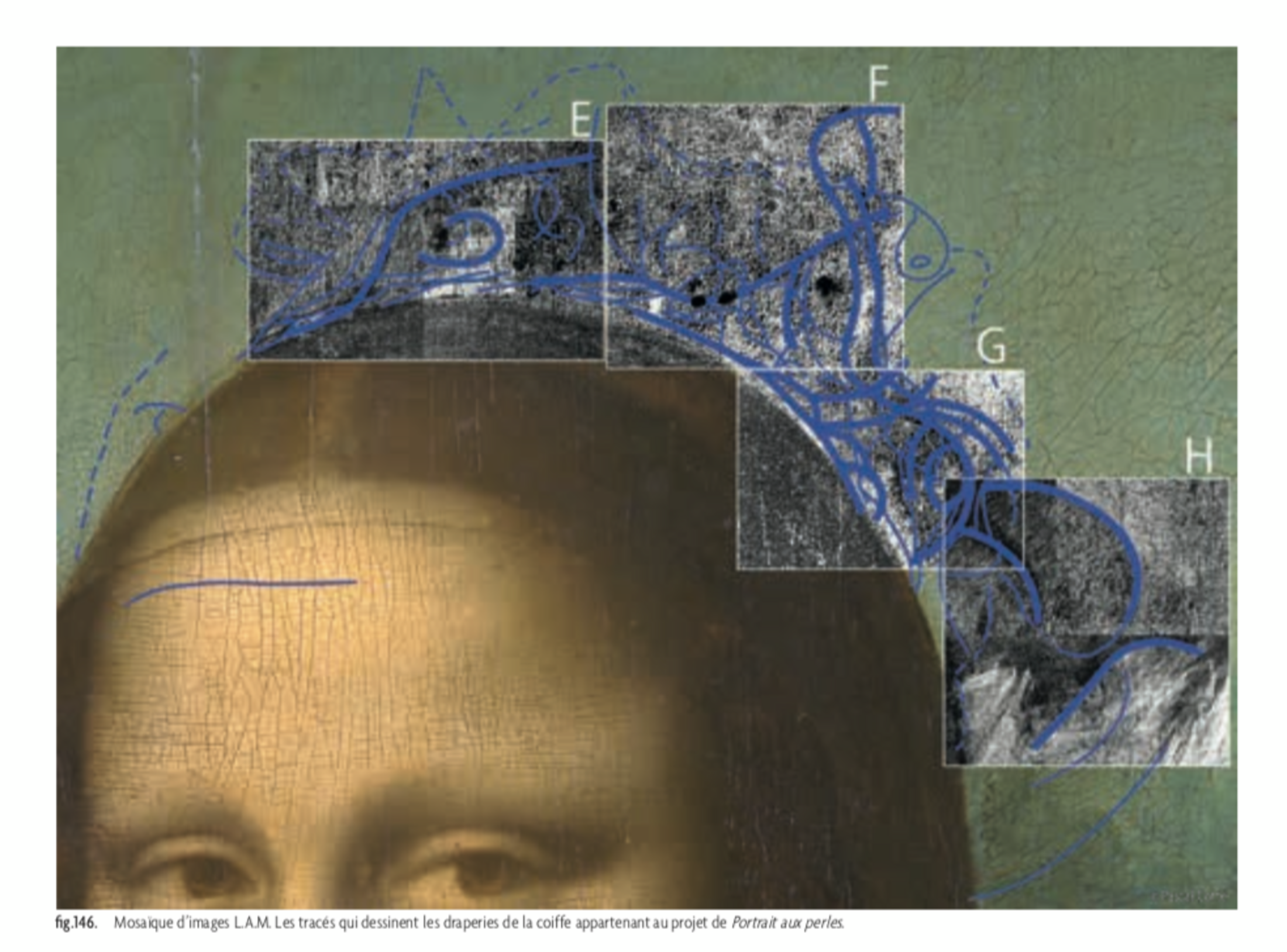

Like Pascal Cotte, the catalogue authors make a connection between the Mona Lisa and Maddalena Doni, a portrait painted by da Vinci's contemporary Raphael. “In the two works hair was fetched back behind the shoulders. The long ringlets on either side of the Mona Lisa's face were painted in a second phase, as well as the embroidery with Arabesque pasterns” which adorn the dress. All these things had been described in detail by Pascal Cotte.

On October 25th 2019, during a symposium organised alongside the exhibition, the C2RMF detailed its findings. In her final legal notice, Cotte's lawyer Sophie Viaris de Lesegno states that in the symposium, as in the catalogue, the establishment “appropriated to itself the results of Pascal Cotte's researches and discoveries by presenting them as unprecedented discoveries coming from new research in scientific imagery”.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

When questioned by Mediapart, the Louvre confirmed that it had carried out its own research after the work done by Cotte. “On the issue of the Mona Lisa, some X-ray fluorescence mapping carried out in 2019 was shown during the symposium in October and the recent hypotheses on the painting are based on these new documents,” the museum said. “The images published in the exhibition catalogue are not those of Mr Cotte but those carried out by the C2RMF in 2008 and 2019.” Moreover, said the museum, “Mr Cotte sees other states of the painting below the actual Mona Lisa, a theory which the two curators don't go along with. So they did not not pick up on this idea.”

“I note that they carried out searches to find my discoveries,” said Pascal Cottee. “I was the first to bring to light the Florentine dress in the painting's under layer. The fact that the C2RMF rediscovered them with techniques other than mine is all very well, but from an ethical point of view the least they could have done would have been to mention my previous works.”

Neither the Louvre nor the C2RMF has responded to Pascal Cotte's final legal warning letter.

The law of copyright could also apply to the current dispute, as much as the complaint of parasitism, which depends on there being economic consequences, which is sometimes hard to prove. “The names 'Louvre' and 'C2RMF' confer on the exhibition catalogue a scientific status that it doesn't have,” said one specialist in this area consulted by Mediapart. “The C2RMF could certainly not have written the same thing in a scientific journal, where not citing the works of Mr Cotte could have been considered as a scientific error.”

Mr Cotte's lawyer also attacks what she calls the “denigration” that Pascal Cotte has suffered. In fact some publications – Le Parisien newspaper and science magazine Sciences & Vie – pulled plans to publish interviews with Pascal Cotte after being convinced by the arguments or even, claims the lawyer, the “pressure brought to bear” by the two institutions.

The expert has in the meanwhile continued his work on the Mona Lisa. He is preparing to co-sign an article about the spolvero technique with a scientist who is a specialist in the optical properties of materials, Lionel Simonot from Poitiers University in west central France.

“It's the first time that one has managed to highlight the spolvero in the Mona Lisa,” Lionel Simonot said. “Leonardo transferred his drawing via a pierced sheet by using the black from charcoal, giving the appearance of points on the painting. In the images obtained by Pascal's multispectral camera, you see these points on the edges of the two hands, on Mona Lisa's forehead.”

Pascal Cotte is also working with Bologna University where he is teaching scientists how to use his camera, which in technical terms has still not been bettered by other devices.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter