Michèle Audin, the celebrated mathematician whose father Maurice Audin was tortured and killed by French troops in Algeria in 1957, could have published her book about him in 2012. That, after all, was the year commemorating 50 years of Algerian independence from France. Yet Michèle Audin published 'Une vie bréve' ('A brief life') early in 2013 and in the book she touches but briefly on the details of her father's tragic death, an episode that became known in France as the 'l'Affaire Audin' or 'Audin affair'. She also avoids writing about her father in an overtly-emotional way, and each word is carefully weighed.

Was her approach the right one? Absolutely. 'Une vie bréve' is one of those books that grabs your attention and your emotions by what isn't said, by the low-key events, the attention to detail and the humour. A member of the literary group Oulipo that borrows heavily from the world of mathematics, Michèle Audin has the rigorous imaginativeness of mathematician-poets. Her style inevitably makes one think of another Oulipo writer Georges Perec, author of the celebrated Life: a User’s Manual. Both authors share a writing style which revolves around absence and mere traces of things. In fact she wrote an amusing and erudite article devoted to Perec and geometry.

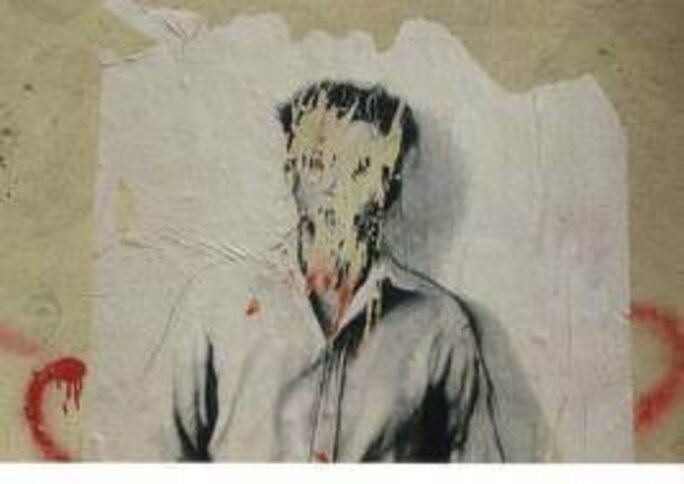

For the three-year-old little girl who threw herself onto the paratroopers who came to arrest her father in Algiers (as she was later told, because she doesn't remember it herself) there was, perhaps, a double loss. One was his death, but the other was that of his legend, which became an edifice of memories and tributes from others – his fellow Algerian activist Daniel Timsit described Maurice Audin as “an angel” - which, however accurate they might be, became fixed in time and place.

She therefore turned towards the reliable, the certain, the little details. These included archives, posed photographs, short family letters, precious notebooks that belonged to a grandmother, domestic accounts ledgers and travel tickets. A plan of Algiers, too, but one which her father used, and the notebooks in which the adolescent Maurice Audin wrote quotations. Including one, recalled by his daughter, “Property is theft”.

An examination of the civil registry shows that the family was one of those that lived through history but left very few traces of its own, rather like the family of writer and philosopher Albert Camus who was born in Algeria, notes Michèle Audin. The old French colonies of Algeria and Tunisia offered, for many from the French mainland, the hope of a better life if not wealth, and that is how Maurice Audin came to be born in a gendarmerie at Beja, not from from the Tunisian capital Tunis. From his birth in 1932 to his death at the hands of French General Jacques Massu's troops on June 21st 1957, Audin's life constantly crossed paths with the army.

“And here I am in front of the great unknown: the schools for soldiers' children,” writes Michèle Audin. “A school made for the poor sons of poor men in the French Army.” Maurice Audin attended these schools that held open the potential for social advancement, first at Hammam Righa in northern Algeria then at Autun in the Burgundy region of east France.

“And then there was literature,” writes his daughter. “Did I not know for example that in the very book where he spoke of the life, and the death, of his father, [the writer] Claude Simon had described these schools as 'children’s penal colonies'?”

But in the family letters themselves little is revealed of these schools and their true nature. The tone is generally one of reassurance; only in passing do we learn that when the young Maurice narrowly avoided dying from meningitis the family was only informed of the incident later.

Along the way, somebody gave the child a taste for mathematics. And as a very young man Maurice Audin got permission from his father to pursue his studies rather than join the army.

Despite the war it was a time of hope

A picture emerges of his life as a young adult. Maurice Audin meets Josette, who is a member of the Algerian Communist Party (PCA), they soon have children – three in all – have to go shopping each day because they do not have a fridge and eat quite a lot of meat. The couple smoke Camelia Sports cigarettes, she spends little on shampoo, they buy ftaïrs or Tunisian fritters at the market and they sometimes go to the cinema. Josette stops her studies, he continues with his thesis and gives “little lessons” to earn some more money and they buy a 4CV car.

The couple give a donation to the Rosenberg cause – the husband and wife convicted of spying in the United States and executed in 1953 – they go to communist party branch meetings and join a group studying Soviet cinema...there is even a mention of buying glue and a large brush to put up posters. This is what we glean from the few family account books surviving from that time.

There are lots of trips that bear witness to itineraries that are hard to imagine for those who only know Algeria or Tunisia since independence; holidays, family trips, and marriages, people travelling thousands of kilometres from the Basque country in south-west France to Lyon in the east, via Algiers. Here, in the telling detail, we get a portrait of an extended France, of the space and distances involved.

That is, in essence, the miracle of this book. It is far from being a “nauseating nostalgia of the Pieds-Noirs” or ”black feet” as French citizens who lived in Algeria before independence were called. Instead it restores an historic time, an era of family, of words, friendships and intimacy to our wider notion of history. It was, despite the war of independence, a time of hope.

The young Audin was working on his thesis (it would be finished on his behalf after his death), he was corresponding with eminent mathematicians, he was getting encouragement. The possibility of being fast-tracked to success beckoned. Perhaps he thought of getting away from the war in Algeria, as suggested by the fact that he looked at the possibility of getting a job in Tunisia, though he quickly abandoned the idea. We find him in Paris having productive professional meetings and there is an encounter along the way with the eight-year-old “poet prodigy” Minou Drouet whose teacher was besotted with her.

But the still round-faced young man with a mischievous look was also serving as the bursar for the communist party, and gave shelter to a party leader who was ill. He had allied himself with those who were fighting for Algerian independence.

'It's tough, Henri'

It was a France that still believed in merit, in fighting for what's right, in moral behaviour and in international conventions that was to die in the torture chamber – which was itself also French. Somewhere between the school reports of a young pupil, the smile of a very young couple – the story of which their daughter relates in her book – lies the mystery of why some showed support over the plight of Maurice Audin, while the majority showed hostility or simply avoided the issue. For there were not that many at the university in Algiers who were moved by the disappearance of the young teacher. And doubtless not many more were concerned when his widow and her children had to flee the paramilitary organisation the Organisation de l'armée secrète (OAS).

In reviving the memory of this man who believed in love and peace, other issues are raised; about daily life and its influence on us, about politics and making choices. It raises, too, issues about danger and the phrase that is the last known utterance of Maurice Audin who had just been tortured when he crossed paths in prison with another prisoner, journalist Henri Alleg, and told his friend: “It's tough, Henri.”

“I have spent years of my life repeating that I didn't want to mix my professional and private lives,” writes Michèle Audin, who has incidentally also written on the Science Academy and the Paris Commune of 1871. But the private and the professional sometimes do overlap. This is shown by the letter, relayed on Mediapart by editor-in-chief Edwy Plenel, that Michèle Audin sent as a rebuke to then president Nicolas Sarkozy in 2008. The scientist, who had just been offered the Légion d'honneur by the French state, had not forgotten that her mother Josette had not even received a reply to a letter she had sent to the president 18 months earlier asking once again that the French state recognised what had happened to her husband Maurice. Josette Audin has since sent another letter, this time to President François Hollande.

That is a separate issue that does not feature in this book. The book itself introduces us to the man, what his daughter knows of him. Last December Michèle Audin was among those who celebrated the 80th birthday of poet and mathematician Jacques Roubaud in poetry at a gathering in Paris. She gave her reading practically without pausing for breath. Afterwards, as people left, she was worried because she had not spoken to anyone about the publication of her book on her father, and was wondering how it would be received. She is doubtless reassured today.

At the same time as her own book appeared, publishers Phebus republished Chez les Weil, by Sylvie Weil, daughter of the mathematician André Weil and niece of the philosopher Simone Weil. It has a preface by Michèle Audin. Once again we see a combination of mathematics, philosophy and political and social commitment.

---------------------------------------------

English version: Michael Streeter