“Under the guise of empathy and tolerance we have let situations develop that we should never have accepted.” That is the blunt response of nursery school headteacher Béatrice when asked about the government's new-found attachment to secularism after the Charlie Hebdo terror attacks of January.

Following those murderous attacks the government swiftly announced an “action plan” for schools based on the “values of the Republic”. At the heart of these values is the commitment to a secular state, with President François Hollande insisting that “it all starts with secularism”. The president also said that teachers are “on the front line” in the fight against home-grown terrorism.

To discover how such initiatives are viewed on the ground, Mediapart visited Amiens-Nord, the northern part of the city of Amiens which lies around 120km north of Paris. The nursery school where Béatrice teaches – Mediapart is not using teachers' full names, in order to protect their identity – is in an area that bears all the hallmarks of an urban ghetto and which experienced riots just two years ago. Amiens is also the city where France's Moroccan-born education minister Najat Vallaud-Belkacem grew up and was educated.

Mediapart originally interviewed Béatrice on the subject of changes to school hours for primary and nursery schools, during which she spoke about the often daily tensions staff had with pupils' families, many of whom are Muslims from the same region of Morocco, tensions which she says the media have shown little interest in. “I spend my time talking to parents who are worried about the presence of alcohol in the king cake, others who worry about what's in the sweets given out for [pupils'] birthdays … I sometimes have the impression that all my time with parents is taken up with such issues,” says the head teacher, who has worked there for eight years. This district of Amiens was classified as a security priority zone (ZSP in French) after the riots of July 2012, during which a neighbouring nursery and primary school was set alight.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Since those riots the area has become calm again, says Béatrice, but the danger of people retreating into entrenched positions on religion is never far away, especially among the large local Muslim population. “The other day a mother again came to ask me if we used Knorr stock cubes in the cooking water, because it has pork in it. I exploded and said to her that I really don't have the time to look into the composition of the water used to cook beans and that, in any case, the school canteen wasn't obligatory!” says the principal, who admits she is close to being overwhelmed and has only one day a week free to devote to the running of the school itself.

She recalls how some parents recently refused to allow their children to take part in birthday celebrations organised by the school. “One mother said it was paganism!” says Béatrice with frustration. Some – a small minority – refuse to allow their children to be photographed.

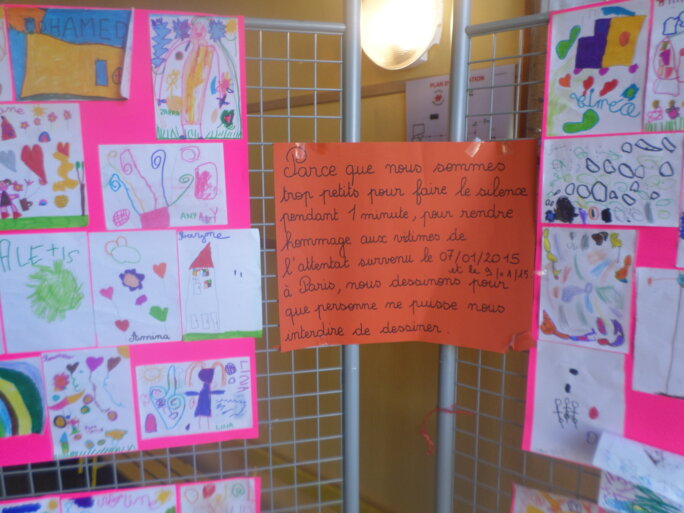

According to staff at the school, last month's terror attacks in Paris created a feeling of awkwardness in their relations with some parents. “We felt a real uneasiness in the days that followed. Very few parents spoke to us about it,” says Béatrice, who says her staff were “very shocked” by events in the capital. For example, the wall display at the school entrance that was created by pupils as a homage to the victims of the attacks (see photo below) produced not a single comment or remark from parents, much to the headteacher's dismay.

“One Muslim mother came to see me and said: 'But what are you going to think of us? That's not Islam.' I told her that obviously I didn't make facile links between Islam and terrorism. I even said to her that if she didn't agree with what happened then she should say so loud and clear,” says one teacher, who like all her colleagues lives in the more prosperous south of Amiens. “One mother also told me that she was afraid about the rise in racism, and was frightened for her children,” the teacher adds.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

In 2014 the row over the alleged teaching of 'gender theory' in French schools – in fact the ABCD of equality programme was simply aimed at promoting equality between boys and girls at primary schools – also caused tensions and permanently harmed relations between the school and some parents. “Eighteen mothers came to see me and and showed me some nutty text messages which claimed that the school was going to teach its pupils how to masturbate,” says school principal Béatrice. And on the first day of an appeal for parents to keep their children away from school in protest, many youngsters were indeed absent.

Eventually, after many discussions with families, a meeting was organised to try and defuse the tension. “The atmosphere was electric,” recalls one teacher. Ultimately staff were able to re-establish trust with most parents but in the weeks that followed four pupils – three from primary and one from nursery classes – were taken out of the school by their parents. “First of all they were enrolled at a private Catholic school and today they're being educated at home,” says the principal.

At this school mothers who wear the veil – and they are in the majority – have never been prevented from accompanying pupils on school trips, unlike at some other schools who have applied a strict interpretation to the barring of the veil in French schools. This, says the principal, is evidence of their pragmatic approach. But they cannot escape the issue, especially as some schools in the south of Amiens itself have stopped mothers with veils from going on school outings. “During one trip, none of the mothers who accompanied us wore the veil. This was quite by chance – the others should have put themselves forward [to go on the outing] sooner – but several mothers who do wear the veil later questioned me about it,” says the school principal.

Muslim families sending their children to a Catholic school

At a neighbouring primary school in Amiens-Nord, which deals with the same families as the nursery, the principal has a different take on events. “Overall, things are going quite well,” he says. “The most important thing is to defuse these questions. You have to be comprehensive and show diplomacy, because if you keep clashing with families you pay for it in the long term.”

For this headteacher, it is all about the stance a school takes. If the institution is always on the defensive it can only lead to people retreating into entrenched positions, he believes. However, the principal does admit he is worried by the issue of children being withdrawn from school in the wake of the 'gender studies' controversy. “It's a new concern. Is the solution that there should be a Muslim school? Personally I'm not in favour of this because that would add more segregation to segregation, but it's a legitimate request as the majority of families here are of the Muslim faith and in the area there is only a [private] Catholic school,” he says.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

In fact, that Catholic school, Notre-Dame de Bon Secours, has already attracted more and more Muslim families in recent years. “Today I'd say that the majority of the families whose children go to the school are Muslims. But don't they see the cross there or what? They can hardly miss it!” says Agathe, a Christian mother of African origin whose children go to the school, with a smile. A Muslim mother who sends her children to the private school meanwhile explains: “The children are better supervised. They call us straight away if our child is late or absent...” She declines to give her name but says that the fact that the school is Catholic is not a problem for her, and that, indeed, it guarantees tolerance for religious practice. When asked if she would like to see a Muslim school in the area, this mother replies: “I don't know. The most important thing is that the children learn well.” According to Agathe, meanwhile, the arrival of so many pupils of North African origin at Notre-Dame de Bon Secours has led to the “whites” leaving and sending their children to the local state schools instead.

In this tough and deprived area, it has been a struggle to encourage social mixing. The local Arthur-Rimbaud collège or secondary school – which caters for children aged 11 to 15 – is in a special education priority network (REP+ in French) which means that it is among the 300 most problematic schools in France. Yet the staff are proud of the social mix that they have achieved at the school. After the 2012 riots officials and teachers pushed to get a school bus route between the collège and the nearby middle class area of Saint-Pierre. By showing that its exam results were in line with the average for the département – akin to a county – that the school has new buildings and that its teaching team has remained unchanged – something of a rarity in priority education areas – the collège has been able to persuade parents in Saint-Pierre to come on board.

“Seventy percent of the pupils still come from less privileged backgrounds but we also have children from middle class families and from families of white-collar workers,” says the principal of the nursery school next to the collège. “There are even teachers who send their children here!”

This is the very same area which, 20 years ago, played its part in the national controversy about the wearing of 'head scarves' in schools, when pupils at the collège were turned away for wearing the veil. This nation-wide issue led in 1994 to a circular by then education minister François Bayrou that banned the wearing of “ostentatious” religious symbols at school. But today the teachers insist that the issue of secularism is not a particular problem. Out of 400 pupils a handful of girls wear the veil and remove them without any fuss when they enter school.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

“The problem, then, is what lies behind the word 'secularism'?” asks one teacher at the secondary school. “I have the impression that, faced with this debate, everyone is a bit lost. At the beginning it was an anticlerical fight more than an anti-religious one. Today I'm not sure that still comes into it.”

The collège witnessed none of the problems seen in a few other schools following the Charlie Hebdo murders and the subsequent minute's silence held to honour the dead. “Sure, there was a pupil who said 'Me, I'm a terrorist' after the attack on Charlie Hebdo,” says one teacher. “But we know them: they know what to say to stir things up. The main thing is not to overreact,” he adds. He was personally astonished to see some pupils at French schools hauled before police accused of condoning terrorism because of remarks they had made at school. The teacher says that the relative calm at the school stems from the fact that they have been intervening on issues touching on religion for many years.

A fight against fatalism

Nearby is the help group ALCO, which was set up to give local children extra tuition out of school hours, and also performs a form of inter-cultural 'mediation' in the schools in this district of Amiens. The association is run by Mohamed El-Hiba, who admits to being slightly irritated by the way that politicians in general and the government in particular seem to have suddenly rediscovered the existence of ghettoised areas and are falling over themselves to come up with miracle solutions. “There's nothing worse than forced unanimity,” he says, referring to the mood that gripped France in the aftermath of the shootings and the marches that took place on January 11th.

“We're living in a totally irrational time, a period of passion,” he says. “The kids who come here indeed ask some disturbing questions but when you're an educator you don't have the right to cut short your explanations. Forcing them to be quiet fuels terrible resentment,” says El-Hiba, who is exasperated that pupils were called on to “be Charlie” - a reference to the 'Je suis Charlie' or 'I am Charlie' slogan that spread around the world after the terror attacks. “When a child gets that shoved in their face, you can understand why they might want to go against the flow.”

He is puzzled as to how promoting secularism is presented as a solution for all the problems faced by ghettoised areas. “There is no miracle cure, we have to stop getting carried away. These are policies for which you need staying power and calmness, certainly not a scatter-gun approach,” says El-Hiba. “Very few people understand secularism. Sometimes it becomes a religion. France today is multicultural, that's acknowledged. So, the only question to ask is, what does one do about it?”. Mohamed El-Hiba himself believes that France has not yet come to terms with the presence of Islam in the country.

“Philosophy and great principles are fine but you need to keep your feet on the ground! We're in an area that is hit by economic poverty and emotional deprivation, by a cultural deficit,” says the head of ALCO, who points to the fact that the local jobless rate is close to 40% in some parts, that there are many single parents who are struggling and that there are many young people with qualifications who are unable to find work.

“There are other priorities,” says Mohamed El-Hiba. “There's no point in giving the kids from here a lecture on secularism, you have to state it in practical terms. We're fighting against a fatalism that many young people here have completely bought into. One of our missions is to talk about school in a different way. They often use very harsh expressions about the teachers. Our work is to explain to them that [the teachers] are there for them, and that success, moving up in society, depends on school - apart from for a few cunning so-and-so’s who have done well without it. It's the school that gives them the keys to power. That's our struggle. To teach them to look at society through the eyes of know-how and knowledge.”

When he is invited into schools for inter-cultural mediation, Mohamed El-Hiba accepts that he is addressing the pupils every bit as much as the teachers. For example, he has just held a discussion about why so many Muslims at the collège are absent from swimming lessons during Ramadan. “They were saying to me but sir, [drinking] water is forbidden [during Ramadan]. I told them, do you take Allah for an idiot or what? If you drink without meaning to, he knows...” He also recently had to reassure the head of a local nursery school who was taken aback that a pupil's mother had brought her a 'fatwa' on children's education, by explaining just what this term means in Islam – simply a legal opinion by a qualified Muslim jurist.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Local women from the area also meet three times a week at the association, either for a sewing workshop or for a discussion. Most come thanks to their children and the extra classes that they take. Helena, the woman who is in charge of the discussions, says it allows the women to talk among each other and get of their houses. “We speak about anything and everything but in the end we all have the same problems: guys who get on our nerves and children that we want to see do well,” she says.

The topic of school often crops up in conversation. When she is asked about the tensions described by the principal of the neighbouring nursery school, Helena is not surprised. “These women feel uneasy because they sense hostility towards them and who they are. That didn't start with Charlie, but it is worse now,” she says. There are sometimes major misunderstandings with the school. That morning a mother had said she was very shocked because a teacher had said to a class of seven and eight-year-old children: “Are you making fun of me?” [editor's note, the French expression was “vous vous foutez de ma gueule?” - the verb 'foutre' is often used in expressions that are much cruder, for example 'va te faire foutre' meaning 'fuck off']. “For them [foutre] is really a rude word and that's serious. Even so, it's not like some of the stupid things that their kids say to us, but hey, it's always good to talk!” says Helena.

Helena, who comes from Portugal, says she is always surprised by how much is left unsaid in French society. After the January attacks she went to a reception at the local sub-prefecture on the subject of state policy in local residential areas. “There was talk of urban contracts and so on, but not once was the word 'religion' mentioned. It's absurd! It shows the extent to which there is still a problem. I don't personally have that problem, I like to call a spade a spade.”

The private discussions among the women are certainly frank and lively. “Yesterday we had a long discussion on the publication of cartoons of the Prophet. They all attacked Charlie Hebdo's obstinacy. I told them: 'Frankly, if you think that your prophet has a dick for a head then, really, it's you who has a problem!” Some were shocked, others laughed. One even replied: 'You're right Helena, real religious people think like you',” says Helena, who is herself an atheist, with a smile.

The number of young people who take extra lessons – ALCO looks after 176 youngsters from the area – shows the concern that these families have about the local schools, even if their academic ambitions for their children are sometimes limited. “The other day we had a bit of a set-to with one mother,” says Helena. “Her 14-year-old daughter is doing very well at the collège but the mother has absolutely no ambition for her, she says she already has a cousin who's waiting in the homeland to marry her. I told her: 'But your daughter, she could be a minister!'”, says Helena, in a reference to education minister Najat Vallaud-Belkacem who grew up locally. But right here and now such an outcome seems so unlikely that the local women take it simply as a throwaway line.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter