In their shooting attack on the offices of satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo on January 7th, in which 11 people were murdered, brothers Chérif and Saïd Kouachi wiped out two generations of artists who made up the cream of French cartoonists: Georges Wolinski, 80, Cabu - who would have turned 77 six days later – Honoré, 73, Charb, 47, and Tignous, 58.

The January 7th shootings were the brutal end of a long and colourful page of a very particular form of French journalism, and whose collective work has no parallel in the Anglophone press.

Wolinski and Cabu (real name Jean Cabut), who were recognised worldwide for their talent, had been at Charlie Hebdo ever since its launch in 1969, and had earlier worked together on its predecessor, the magazine Hara-Kiri, as of its beginnings in 1960.

Honoré, Charb and Tignous joined the Charlie Hebdo team when the magazine was relaunched in 1992, after it had collapsed 11 years earlier due to a lack of funds.

“There’s no need for any wriggling around, they were the best,” said Chatherine Sinet, wife of cartoonist Siné (Maurice Sinet), 86, whose long collaboration with Charlie Hebdo had ended in acrimony and his departure in 2008. “Frenzied hard workers, all of them, incredible talents." Their weekly editorial meetings were followed by wild and legendary parties, from which some would abstain.

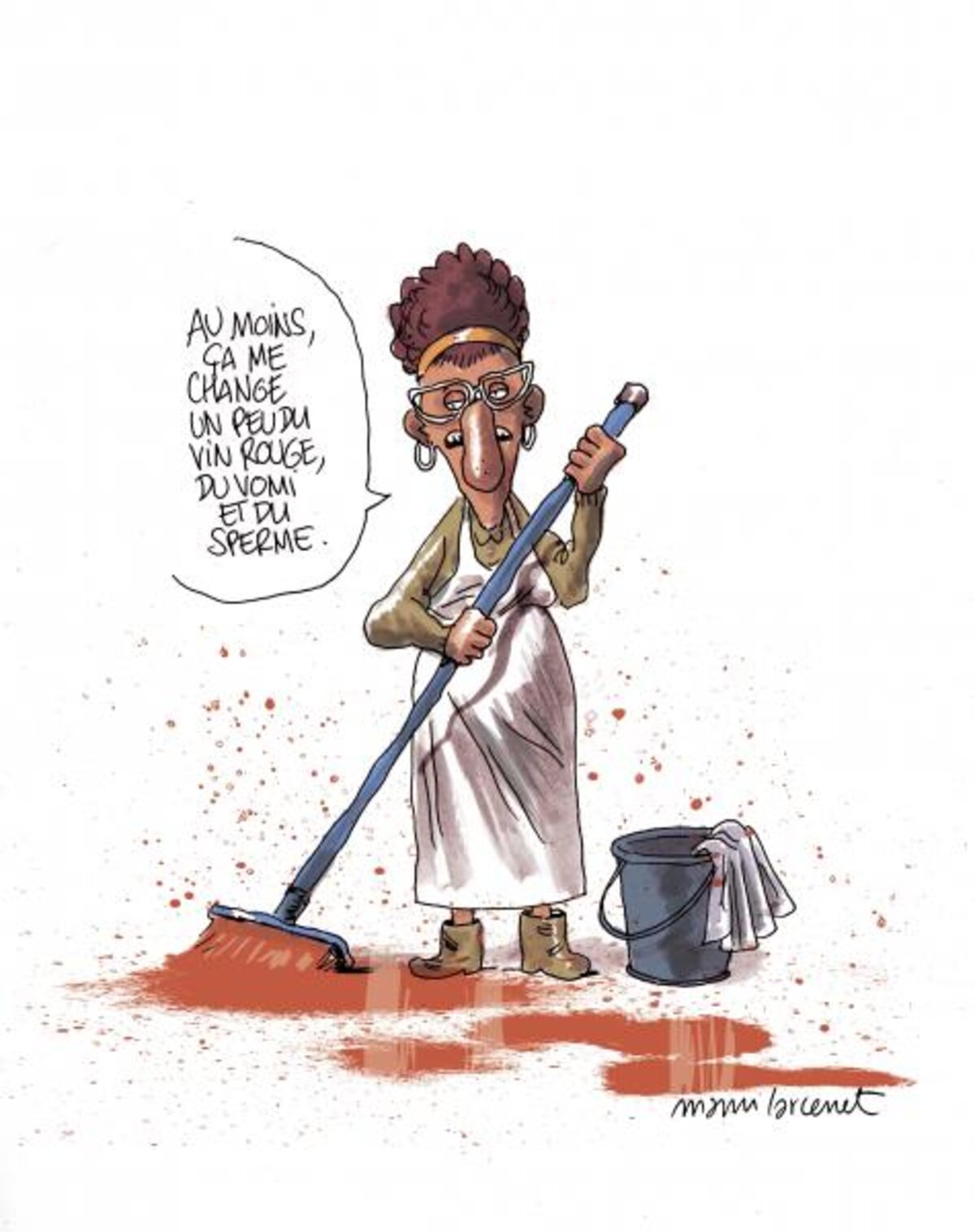

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Above: a January 2015 cartooon, after the massacre, by Manu Larcenet: the cleaning lady, wiping up blood, says "At least it's a bit of change for me from the red wine, vomit and sperm".

Chatherine Sinet, who became the editor of Siné Hebdo, the weekly cartoon magazine her husband set up after leaving Charlie, and then that of Siné mensuel, the monthly that succeeded it, had known the elder Charlie cartoonists for some 50 years. “They brought, and then maintained, a new spirit,” she told Mediapart. Their collective story is a rich and long trail of passion and conflict.

In the early moments of the May 1968 civil uprising in France, Siné was joined by Wolinski and Cabu – along with other cartoonists who would also later work on Charlie Hebdo, including Reiser and Willem - on the newly-launched magazine L’Enragé, which supported the revolts and which declared on its front page the many uses it could be put to, from gas mask to fuses for Molotov cocktails. “They were representatives of this incredible spirit of freedom that began to blow just before May 1968,” recalled Chatherine Sinet. “We could at last get to grips, while laughing, with subjects that were never talked about, beginning with ecology.”

“Those people had masters,” said Stéphane Mazurier, a historian and the author of a thesis on Charlie Hebdo. “Mad magazine in the United States for Wolinski, among the French in the period 1930 to 1950, like Cazals and Bosc, for Cabu for example. But I am not certain that they have had epigones. You find traces of their sense of humour today on television, on [TV shows] the Guignols de l’info or Groland, but not more than a few signs, and not very much in other press publications. The principle inheritors of the founders [of Charlie Hebdo] were in fact among their ranks. This was the second generation, Ruz, Riss,Charb, who all came at the beginning of the second era.”

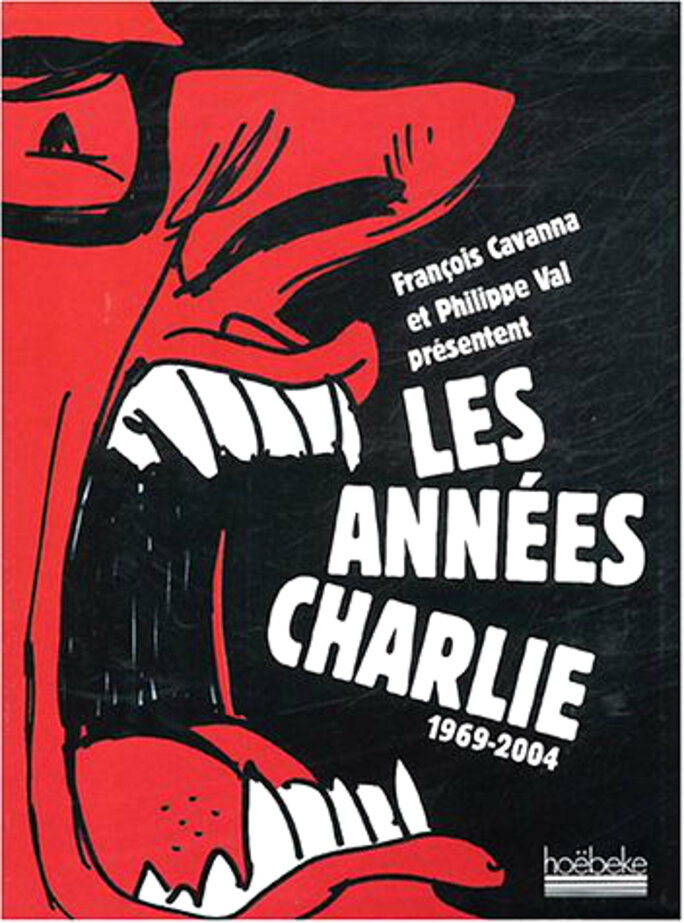

Above: Les années Charlie (The Charlie Years), published in 2004 by Hoëbeke

Once on board, it’s very rare that anyone leaves. “Charlie was like a clan,” recalls publisher Lionel Hoëbeke, who was close to the cartoonist and writer, and Hara Kiri and Charlie Hebdo co-founder, François Cavanna, who died last year. “It was very difficult to enter it, and almost impossible to leave. It is death that has separated the historic gang.”

“It was a gang as of 1960,” added Hoëbeke, whose publishing house has produced seven books by Cavanna. “Then, with the second era of Charlie there was a second generation that was integrated, and that led to a new gang which was established around the initial hard core.”

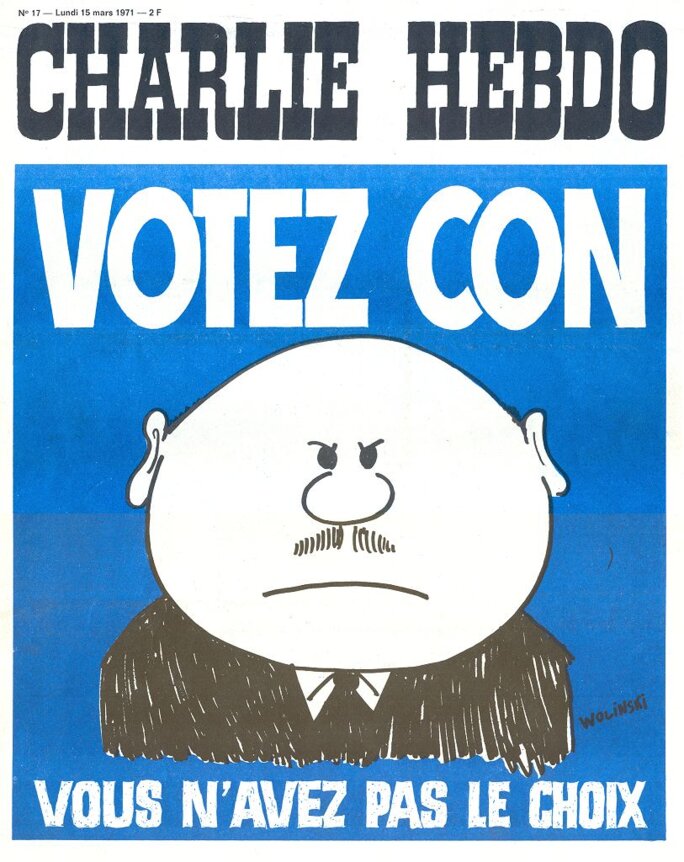

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Above: 1971 Charlie Hebdo cover reads, (in rough translation): "Vote cock, you have no choice".

Philippe Val, who edited the magazine from 1992 until 2009, tried to bring in new cartoonists, like the talented Joann Sfar in 2004. But such attempts rarely succeeded, and Sfar left the magazine after just more than a year. An exception was Riad Sattouf who, arriving in his mid-20s, drew for ten years until last October a regular weekly series entitled ‘The secret life of the young’.

Readership collapsed in 1981, along with the Right

"The thing that characterised them above all was their outspokenness, their independence. No compromise was possible," Hoëbeke remembers. "In any case, if a cartoonist went off to try his luck elsewhere, he soon came running back." Some did work elsewhere but would not pitch the same work to other publications. Wolinski, for example, did not generally publish in the weekly newspaper Le Journal du Dimanche, which he joined [as a contributor] in 1968, the same kind of biting, unsettling cartoons he would churn out for Charlie, despite what he himself affirmed.

Another example of this is Cabu, whose drawings for Charlie were inspired by the news of the moment, or the absurd, but who kept his antihero Le Grand Duduche, a rather gormless, lazy, irreverent schoolboy, for the columns of Pilote, a weekly comic that shook up youth magazines in the 1960s before becoming a monthly in the 1970s.

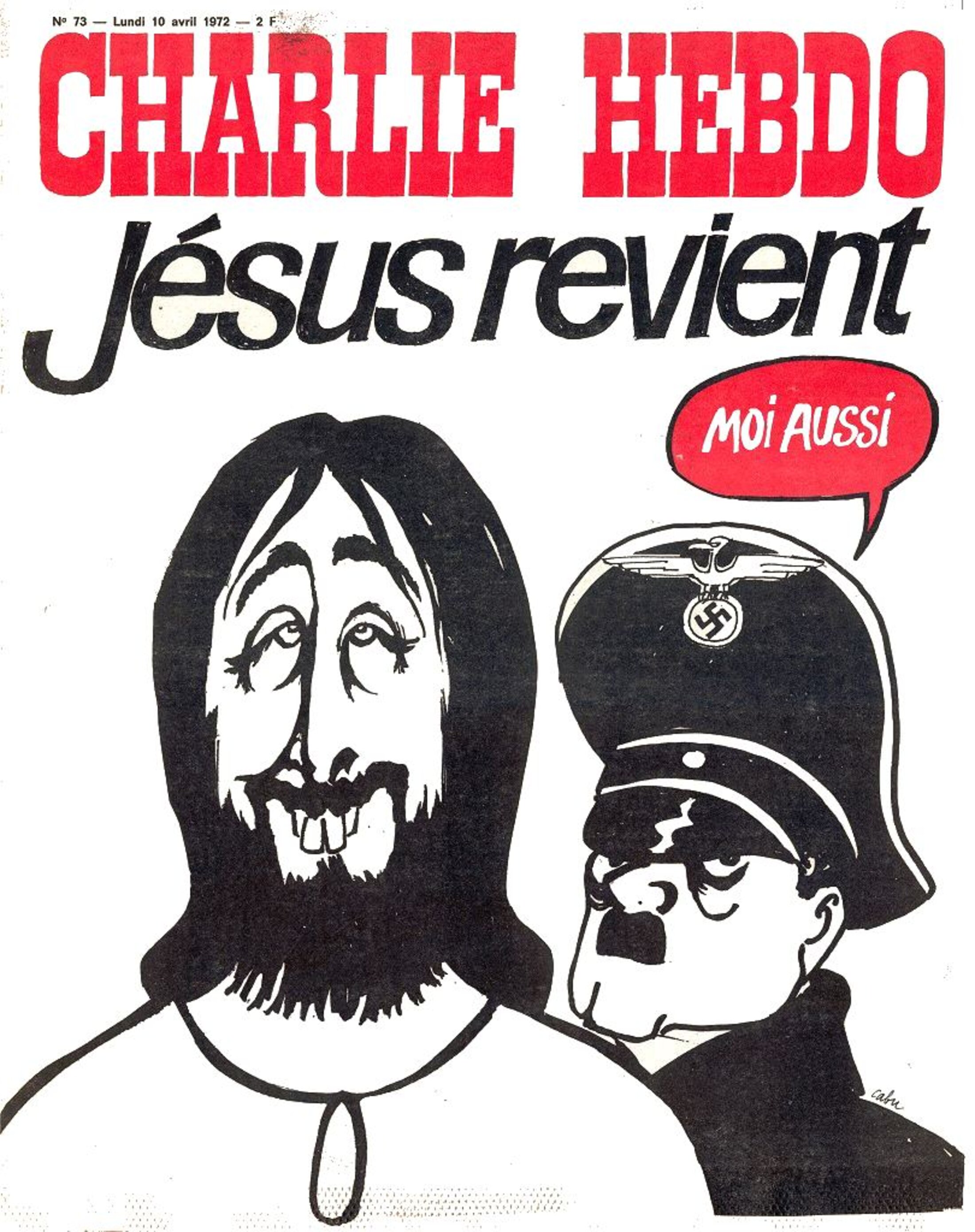

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Above: by 1972, Cabu's drawings, like this one, had lost the dreamy quality of Duduche.

When Le Grand Duduche arrived at Charlie, he wasn't quite the same as at Pilote, he had become politicised at the same time as Cabu during the 1970s – even if I think in retrospect that this Grand Duduche was not the one his creator preferred," said Alain David, editor at Futuropolis, a comic book publisher, who published three of Cabu's books at Vents d'Ouest.

If even Cabu's favourite character changed when he went to Charlie, it was because there was an editorial line at the magazine. "It is undeniable, there was a line," said Liliane Roudière, executive editor at women's magazine Causette who was Charlie Hebdo's communications director from 1998 to 2008, without being more precise. "Charb, Luz and also Jul had enormous respect for the founders, who liked them a great deal, it was a good mix, " she said. This was no surprise, since to be accepted, a new cartoonist had to be really determined. "There was a harsh selection [process]. You had to be opinionated, really want to join us and admire the cartoonists who were already there, to have any hope of your drawings being accepted, and then of being hired," Roudière said. "After that, it could only go well."

Although all Charlie's cartoonists had total freedom, not all of them were published in its columns. This rule was brought in right from the magazine’s first issue and dated from its predecessor Hara-Kiri. Cavanna had founded that satirical journal with humourist George Bernier, who took the name Professor Choron for his persona, but it was Cavanna who was key to creating first Hara-Kiri's, then Charlie's, particular chemistry.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

"Cavanna had this incredible talent for distinguishing among the people who filed through the newsrooms with their portfolio of drawings – sometimes just three scribbles – the ones that were destined to become the geniuses they later became," Hoëbeke said. "And all of them – Reiser, Cabu, Wolinski – they all always spoke of him with total respect and recognition. In that environment, where everyone addressed everyone as "tu" [the familiar form of address in French, as opposed to "vous", the polite form] after five minutes, Cabu never got beyond "vous" with François."

The original team at Hara-Kiri – which called itself "le journal bête et méchant" (the silly, wicked paper) – "were all chosen by Cavanna, but their other point in common was that they could not get their drawings printed practically anywhere else," said Patrick Gaumer, a comic book historian who knew all of them personally from the early 1980s. Cavanna not only picked them, but he pushed each of them to find and perfect their own style, particularly Reiser and Wolinski.

This joyful band – Wolinski and Cabu, but also Reiser, Gébé and Topor, and later Willem – was often irreverent, vulgar, pornographic or insulting. Hara-Kiri was banned twice, in 1961 and in 1966. But after the upheavals of May 1968 the journal rose to glory.

Once it was doing more than just survive, the team launched a second monthly based on the Italian magazine Linus, named after the character in Charles Schulz's comic strip Charlie Brown. But for the French version adapting this mix of American comics trip and the first art-house or erotic comics, Cavanna and Wolinski chose simply Charlie, after Schulz's hero. The magazine would appear under that moniker through to 1981.

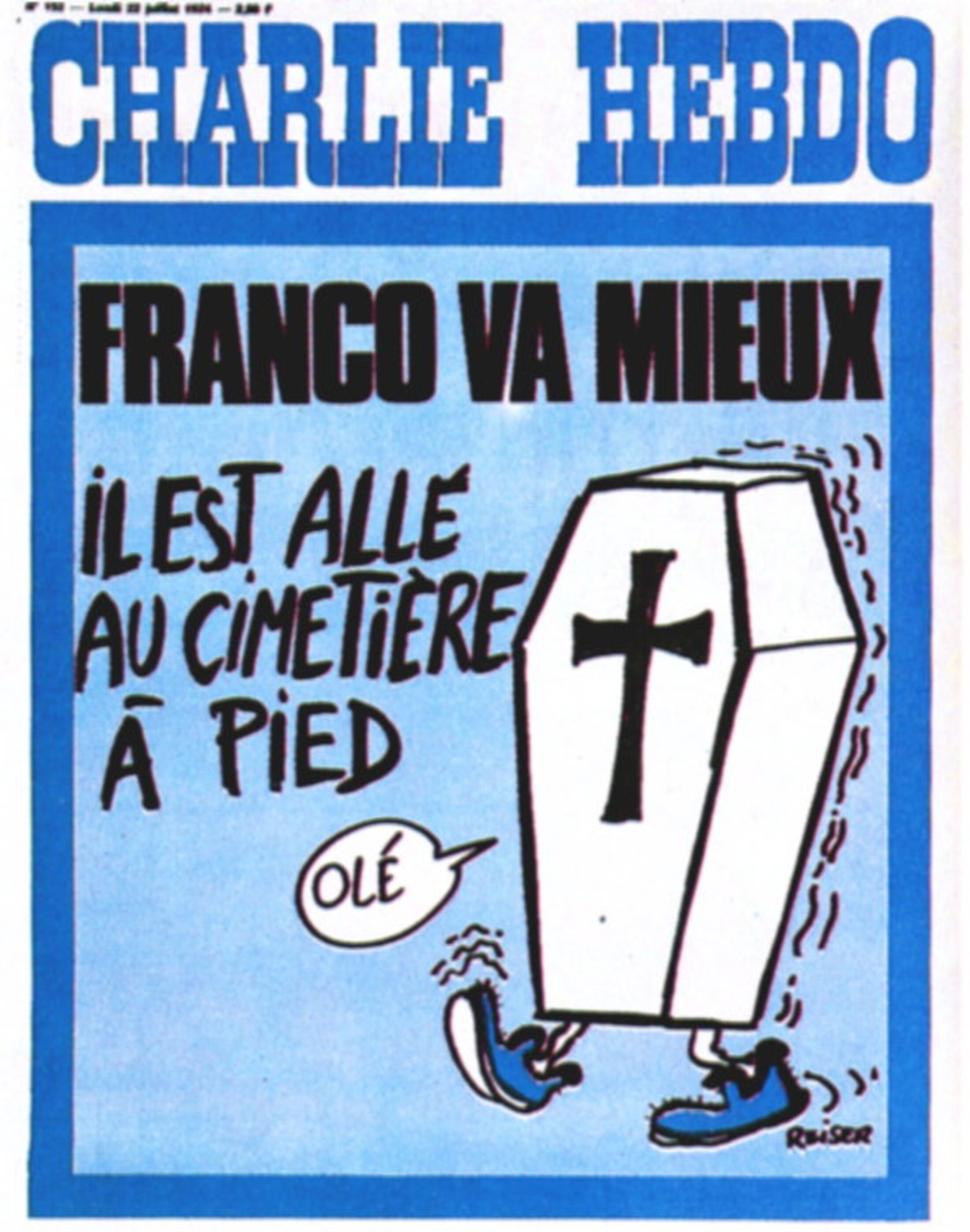

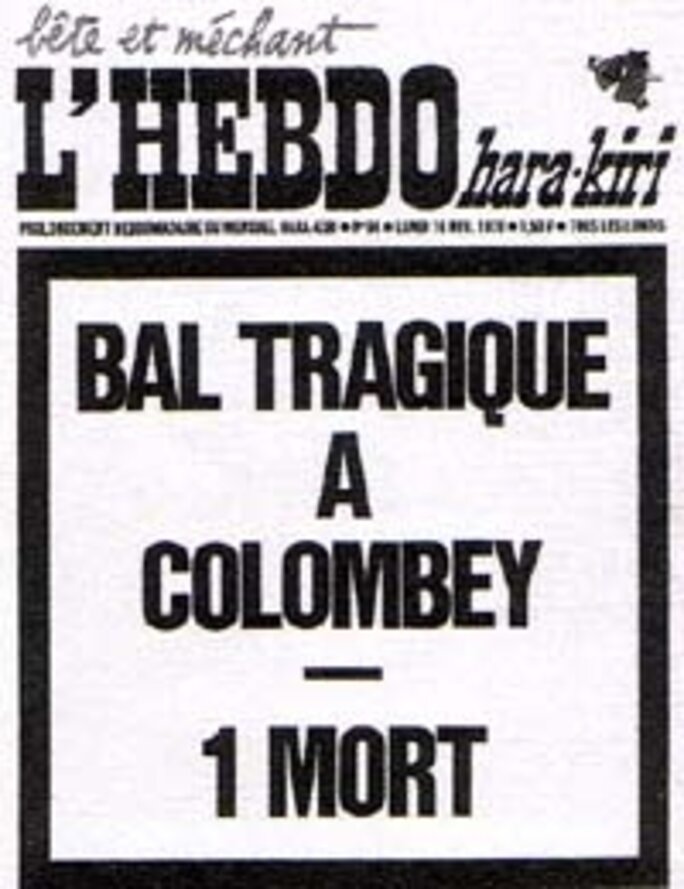

Fittingly,the weekly version, Charlie Hebdo, was born of a front cover that gave offense. Hara-Kiri had launched a weekly spin-off in 1969, but it was banned in late 1970 because of its controversial front page, "Bal tragique à Colombey: 1 mort". This was a sardonic reference both to the death of General Charles de Gaulle at his home in Colombey-les-Deux-Églises and to a story of a fire a week earlier in a discotheque in which 150 people had died, labelled in the press as "the tragic ball". To get round the ban, Hara-Kiri Hebdo became Charlie Hebdo. But with too few readers and too little money, its operations were suspended in late 1981 - when the Left for the first time in the Fifth Republic, came to power in France - and for the next 11 years.

Then in 1992 Cabu, Gébé, the singer Renaud and Philippe Val, who had just left another satirical publication, La Grosse Bertha, bought back the name, on Wolinski's suggestion. Cavanna, Cabu, Wolinski, Gébé, Willem and Siné, who had joined in 1981, were still there, and the younger generation of cartoonists came on board.

'We are beside ourselves with grief'

During these 20 years of maturation and transformation, Charlie’s tone has considerably evolved. “At the start, there was nothing explicitly political,” recalls Patrick Gaumer.”Apart from the bad-taste humour and the news section, we were also, with Gébé and Topor, a lot into readapting images, from ads, with bizarre photos, in the spirit of surrealists. Then society changed, and their drawing changed. Along with others, their publication in part sowed the seeds for May 1968. Then, in the 1970s, the political side became stronger still, even if the libertarian and anarchist bent had always dominated. Of course, Cavanna can be called a man of the Left. But Reiser happily proclaimed that he couldn’t care less about politics, and Choron was a completely anarchic right-wing guy, capable of absolutely monstrous tirades.”

Catherine Sinet agreed: In the beginning, and for a long time, they weren’t political enough for Bob’s [Siné’s] taste, who didn’t want to go there,” she said. “In L’Enragé, it was him, all the same, who got Wolinski to do his first political cartoon. But Reiser had insisted, lots and lots, that he join them.”

But a radical political engagement was not to be. “Wolinski said, very lucidly, that he took part in May-68 so that he wouldn’t become what he finally did become,” commented the historian Stéphane Mazurier. Wolinski was for years teased about his bourgeois tastes, and who was, according to Mazurier, “fascinated by money and success, serving tea in a porcelain service set”. Yet, throughout the years, ‘bourgeois’ Wolinski was present every week without fail at the editorial meeting desk where he would finally be shot dead.

Cabu was also a loyal old timer. “It was their family, in effect,” said Alain David, editor at comic book publisher Futuropolis. “For Cabu and Wolinski, there was always pleasure to come, the desire to continue participating. To make use of this space of liberty that they had contributed to creating.”

Enlargement : Illustration 8

Above: ‘Wolinski: 50 years of drawings’, an album of the cartoonists work over five decades and which was published alongside a 2012 exhibition of the same name at the French National Library in Paris.

A desire that was still intact despite the tensions that slowly mounted with the political line taken by Philippe Val, the tone and fixations of which became eventually distanced from the views of most of the magazine’s cartoonists. Val, in favour of NATO’s intervention in Kosovo in 1999, who called, during the 2001 Durban World Conference Against Racism, for the French Left to make clear its stance on anti-Semitism, and who was an ardent supporter of the 2005 referendum on the European Constitution, had for long irritated the ranks of the libertarian Left.

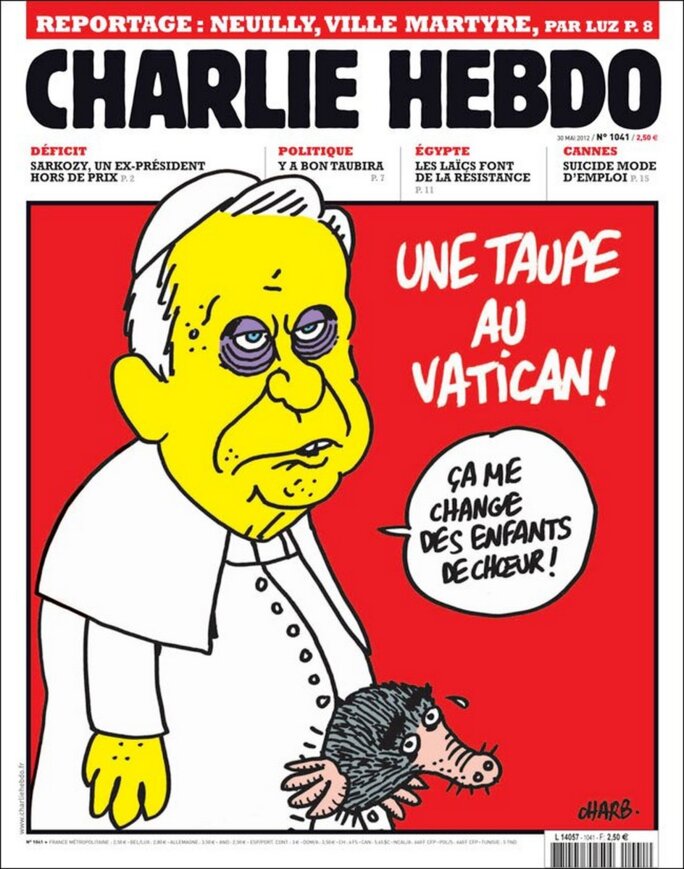

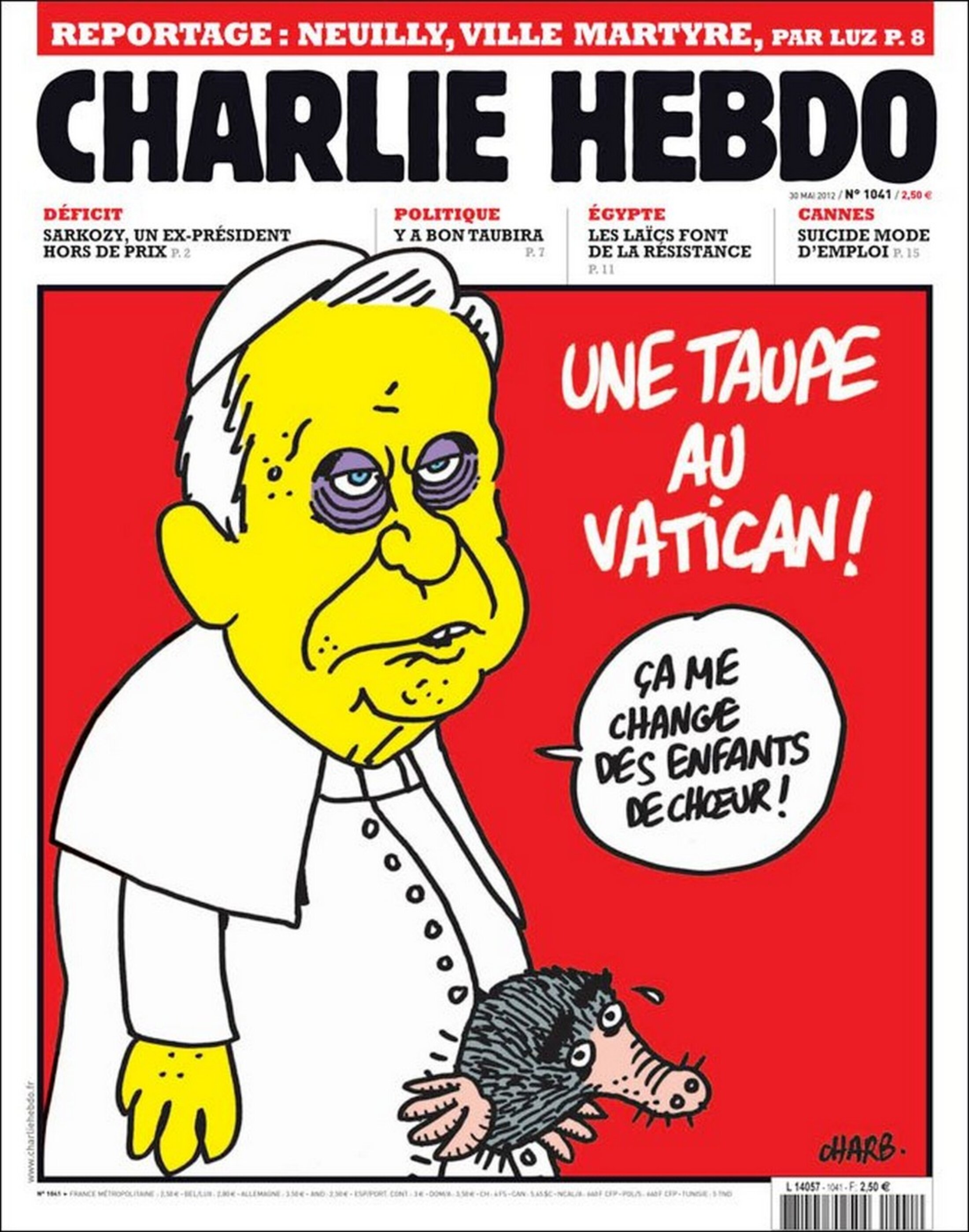

Enlargement : Illustration 9

Above: this cover from May 2012 refers to the leaks of damaging revelations obtained by a journalist from an inside source at the Vatican. “A mole at the Vatican” reads the headline, besides which Pope Benedict XVI comments: “It gives me a change from choirboys”.

Even if Val’s mounting neo-conservatism managed to ally itself with the anti-religious combat of his cartoonists in their lampooning of radical Islam, the atmosphere was changing. “In the first period of Charlie, the place which concentrated all was the publication, and above all the Tuesday evening meeting for going to press,” recalled Catherine Sinet. “The doors weren’t opened before the front page was finished, and it was something of a fiesta every week even if people didn’t see much of each other outside. With the line that Val took people talked less together. In general among cartoonists there is a lot of kidding around, but there there was less joking. During the editorial meeting on Wednesday some kept quiet, others complained very loudly, like Siné or Charb, while others didn’t go there any more. On the other hand, then people met each other in private, and we knotted very strong links with Tignous and Charb, for example.”

In July 2008 came the final blow. Siné was sacked by Val after writing in his regular column about then president Nicolas Sarkozy’s son Jean, in which he alluded to the young man’s Jewish fiancé in an ambiguous manner. “It was an implosion, the old friendships were broken, a real split,” said Lionel Hoëbecke. Cavanna was very forthright in opposing Val and was supported by Tignous and Willem, while Cabu swapped from one side to the other and Wolinski stayed neutral. Charb appeared to distance himself from Siné, with whom he was previously close. Meanwhile, Siné and several professional colleagues, including some regular contributors to Charlie Hebdo, founded his own magazine, Siné Hebdo, a weekly which was later transformed into a monthly, Siné Mensuel.

It was not until 2009, when Val left Charlie Hebdo to take up his appointment, pushed by Nicolas Sarkozy, as editorial director of French state radio station France Inter, that the worst of the storm passed. Nevertheless, while Charb took over as editor of Charlie Hebdo, the relationships within the clan of cartoonists never properly recovered.

The massacre on January 7th brought the controversy over Siné into proper perspective. “It was all the same a family,” insists Catherine Sinet. “We hit out at each other, quite roughly, as in any self-respecting family. But today we are besides ourselves with grief.”

-------------------------

English version by Graham Tearse and Sue Landau.