A group of 16 organisations active in the defence of human rights in general, and those of migrants in particular, who include the French Human Rights League, the Syndicat des avocats de France, a lawyers’ union, the major French charitable institution Secours Catholique, and migrant aid groups Utopia 56, l’Auberge des Migrants and the Information and Support for Immigrants Group (GISTI), have filed a legal challenge with France’s Council of State, the country’s supreme administrative court, against the “one in, one out” migrant return scheme agreed this summer between the British and French governments.

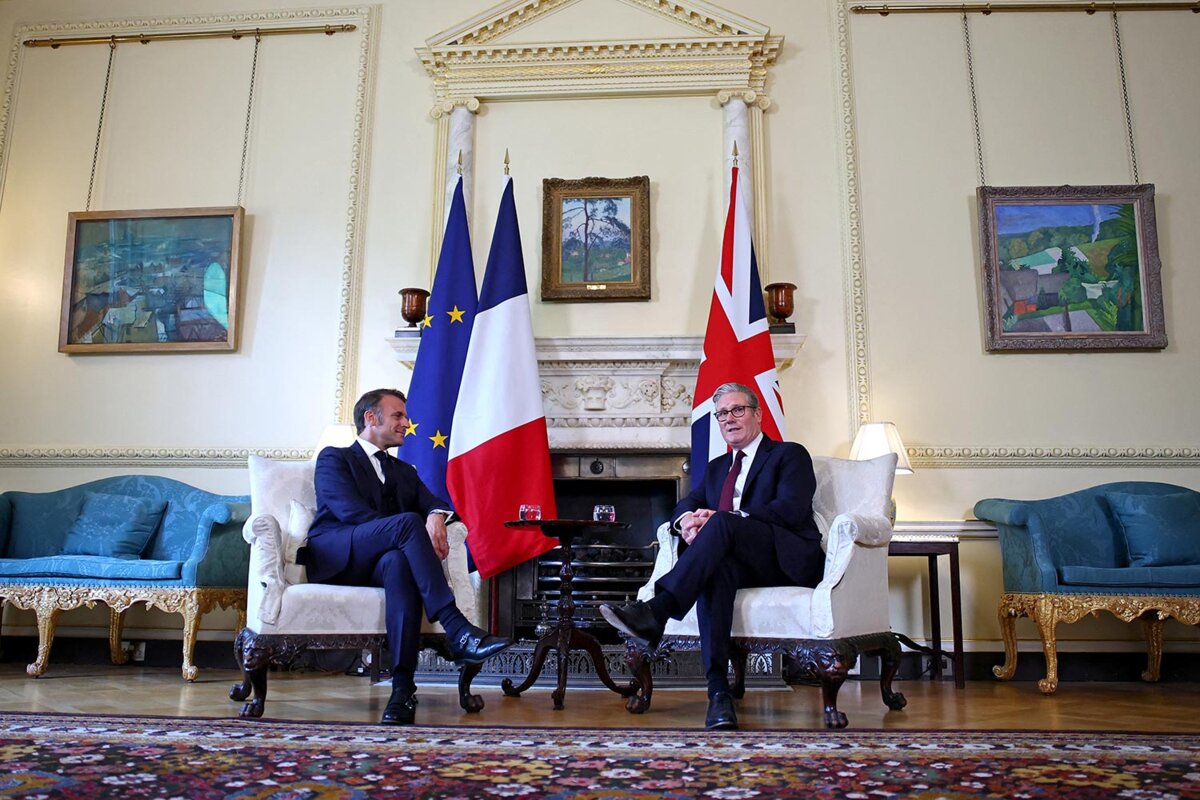

In a statement published on October 14th, the petitioners described the treaty, which was agreed in July during a meeting between French President Emmanuel Macron and British Prime Minister Keir Starmer, and which came into force on August 6th, as an “agreement of shame” and “migratory bargaining”, and above all, they argue, it is “tainted with illegality”.

The treaty was promulgated in France by a decree. However, the NGOs and associations argue that this was done in contravention of an article of the French constitution that requires parliamentary approval before the decree can be issued.

Under the terms of the treaty, a migrant arriving in Britain via a clandestine route – typically crossing the Channel from France in overcrowded and fragile rubber dinghies – can be sent back to France, from where an asylum seeker, who has been legally processed and whose application for asylum is approved, will be accepted by the British authorities in exchange.

Official British figures estimate the number of people who had arrived this year in the country via small boats had, by September 29th, totalled 33,556. But that figure was already significantly surpassed earlier this month when 1,075 people were recorded arriving from clandestine crossings of the Channel on one day alone. That is despite the official notices posted in sites around France’s north-east Channel coast presenting the existence of the treaty and warning of the consequences of arriving illegally in Britain.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The number of people who arrived illegally and who have been returned to France since August under the so-called “one in, one out” treaty by last week numbered 26 – out of a list of 245 return candidates prepared by the British authorities – while 18 asylum seekers vetted in France have been accepted in return. The rejected illegal arrivals are mostly people of Afghan, Eritrean, Iranian and Sudanese origin.

“The unauthorised and dangerous crossings of the Channel have not diminished,” observed the NGOs and associations in their statement on Tuesday.

Their submission before the Council of State alleges an abuse of basic human rights for those migrants who are processed, but also, in a more fundamental legal challenge, they claim the application of the treaty breaches France’s constitution because, before the issue of a decree, it was not ratified in parliament.

Explaining this, Lionel Crusoé, a Paris lawyer acting for the NGOs, said that Article 53 of the French constitution sets out that, “in the case of an international agreement negotiated between the French government and a foreign government, when this includes a certain number of issues that require the competence of the legislator”, it cannot come into force “as long as parliament has not debated its ratification”.

“A dozen decisions by the Council of State have been made in the past underlining in a quite binding manner that a decree specifying the enforcement of a law when it concerns an agreement that was not debated in parliament is illegal. We have a well-defined framework of legal precedents,” Crusoé said.

Regarding the moral issues surrounding the treaty, Crusoé commented: “These people, who have [established] a migration project according to their links or relations with the United Kingdom, have the right to a certain dignity,” he added. “This [treaty] plan, which can be compared to barter, is unsuited to an issue involving human beings.”

In their petition to the court, which Mediapart has seen, the NGOs and associations underline that the substance of the treaty is the transfer “in a forced manner” of migrants from Britain to France “which in all evidence affects their personal freedom”. For those migrants being processed under the terms of the treaty, their freedom is restricted “on the one hand in the United Kingdom during the time taken for the examination of the request that France readmits them – which can take 28 days – and on the other hand, the time required for the journey to France from the country”.

Patrick Henriot, general secretary of GISTI, one of the associations mounting the legal challenge, said the treaty’s contents were “totally dehumanised”, and that “the fact that British escorts accompany the people sent back all the way to French territory should be validated by the French parliament”. He said that was the case in a previous agreement between Italy and France over the sending back of migrants. For him, the treaty is unlikely to “pass the control ramp of the Council of State”, whether that be because of the legal issues surrounding its ratification or the nature of its application.

Amélie (last name withheld), a spokeswoman for migrant rights group Utopia 56, said the French and British authorities, who have previously signed numerous agreements to crack down on illegal migration, have “crossed a line” with the treaty. “It’s an attack upon the fundamental rights of those exiled people blocked at the border, and that’s what explains this broad mobilisation and the diversity of the associations behind the [legal] challenge”.

The Council of State will now firstly have to decide if the appeal against the treaty is of a sufficiently urgent and convincing nature to justify its immediate suspension, while it is otherwise due to deliver its ruling on the substance of the challenge in the coming months.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse