On Wednesday the French government formally announced that it was shutting down the environmental protest group Les Soulèvements de la Terre (SLT), which has been involved in a number of high-profile demonstrations, in particular against large agricultural irrigation reservoirs. Since that announcement the country's powerful farming union, the FNSEA, has been keeping a curiously low profile. Its president Arnaud Rousseau avoided giving interviews while its leaders at county or département level around France were under instructions to “make no comment” on the action taken against the protest group. Yet it was this very union which had been leading the calls for Les Soulèvements de la Terre to be shut down.

“The national [leadership] were listened to on this issue. As for us, we just asked for action against vandalism [editor's note, which occurred during protests against sand quarries on June 10th and June 11th in western France] to occur,” Sébastien Berger, president of the union's federation for the Vienne département in western France, told Mediapart. “Our national president passed on the information to the ministry saying action needed to be taken. After that, well, Mr [Gérald] Darmanin [editor's note, the interior minister] is big enough to make his own decisions.”

Union president Arnaud Rousseau had indeed publicly demanded that the government take “action”, via the columns of Le Point news magazine on June 15th. At the time he said that a meeting had been arranged with the minister of the interior “in the coming days”. Then it all went quiet. The meeting, if indeed it took place, has remained confidential. Official diaries have no record of it. On June 15th Arnaud Rousseau did meet agriculture minister Marc Fesneau at the opening of the farming event Journées Nationales de l’Agriculture at the well-known Rungis market on the outskirts of Paris. But as the union's press spokesperson remarked: “He sees Fesneau all the time.”

How is it that the FNSEA hasn't been dissolved when it vandalised and destroyed the Ministry of Ecology?

On June 11th, on the fringes of the demonstration called by SLT, one group of protestors split off to carry out two 'raids'. Lily-of-the-valley plants were ripped up at a large-scale plant nursery, and then some experimental polytunnels were damaged at a site run by the local market gardening federation for the Nantes region. The SLT were protesting both against the environmental damage caused by the extraction of sand at quarries owned by Lafarge and GSM and the use of sand in intensive market gardening.

These symbolic actions recall operations from the past carried out by the organisation for small farmers, the Confédération Paysanne (CP), such as the dismantling of the dairy at the 'farm of a thousand cows' in northern France in 2014, and at a McDonald's restaurant construction site at Millau in southern France in 1999, led by prominent member CP activist Jose Bové.

But several local FNSEA federations, which had already been actively supporting plans for large-scale irrigation reservoirs opposed by the SLT, were outraged by these attacks on the market gardening sites. During a national committee meeting of FNSEA federations the group from the Loire-Atlantique département in west France demanded the “dissolution of this outfit [editor's note, the SLT] and the satellite groups that support it”.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Among the other groups targeted by the federation was the Confédération Paysanne, often known as the 'Conf'. It had not taken part directly in the two protest actions in question, though its logo had featured on the appeals for the demonstration to take place. “The ['Conf's'] flags were there at Sainte-Soline,” said one FNSEA activist, referring to the protests against plans to build an irrigation reservoir in west France in March. Back then the FNSEA federation in the nearby département of Vienne had written to the local prefect or state official asking for the “outright exclusion” of the leftwing 'Conf' from the local Chamber of Agriculture and other representative bodies, because of that group's “stance” and “acts committed at Saint-Soline”.

At the time the FNSEA's Sébastien Berger had declared: “A farming union that calls for a demonstration that's banned, that contravenes three or four decrees by the prefecture and which supports causing damage and injuries, is no longer a farming union.” But while efforts by local FNSEA federations to exclude the Confédération Paysanne have increased in number, they have been rejected by prefects.

Heading for 'civil war'

“After the dismantling of the pump at Cram-Chaban [editor's note, at an irrigation reservoir in west France in November 2021] there were some very violent messages against the Conf, which called for us to be excluded from public bodies and the Chamber of Agriculture,” says Laurence Marandola, the Confédération Paysanne's current spokesperson. “That's simply illegal.” At the time the FNSEA federation in the nearby Charente-Maritime département accused the 'Conf' of “supporting terrorist acts”.

After the June 11th actions against the market gardens, the FNSEA federation for the Loire-Atlantique – known as FDSEA 44 – said that in its view a “red line has been definitively crossed”. The federation stated: “If no decision is issued and no punishment given out, then elected representatives and prefects run the risk that justice will be meted out in a different way on the leaders of this movement and on identified figures from last Sunday who trampled on crops.” FDSEA 44 president Mickaël Trichet then explained to Mediapart: “We're not going to set up militias to deal with it. What's going to happen is that one day people will get out of control. That's what's going to happen.”

“There's total impunity today and it's going to lead everyone to civil war,” FNSEA boss Arnaud Rousseau explained in Le Point on June 15th. “I'm not sure I can hold back my troops for long. I hope that what happened on Sunday will signal the end of what is a form of leniency. Because an incident could occur,” he added.

José Bové, the prominent activist and former Confédération Paysanne spokesperson, thinks that the shutting down of Les Soulèvements de la Terre is evidence of an “authoritarian drift” which makes “absolutely no sense” other than to “impose the interests of a minority of agribusiness managers”.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

“How is it that the FNSEA hasn't been dissolved when it vandalised and destroyed the Ministry of Ecology?” asks José Bové. In 1999 paving stones were torn out from the ministry's courtyard in Paris and environment minister Dominique Voynet's office was ransacked; four people were later fined for their involvement.

“Let's not forget the wrecking of town centres and prefectures … all that could have justified a dissolution in the same way,” says José Bove. “I would never call for the dissolution of a union organisation, but you have to put things into context. The FNSEA is seeking to stop any opposition against its [agricultural] model, by frightening those who oppose it, by calling for movements to be shut down. Tomorrow they'll be calling for the dissolution of the Confédération Paysanne - why not?”

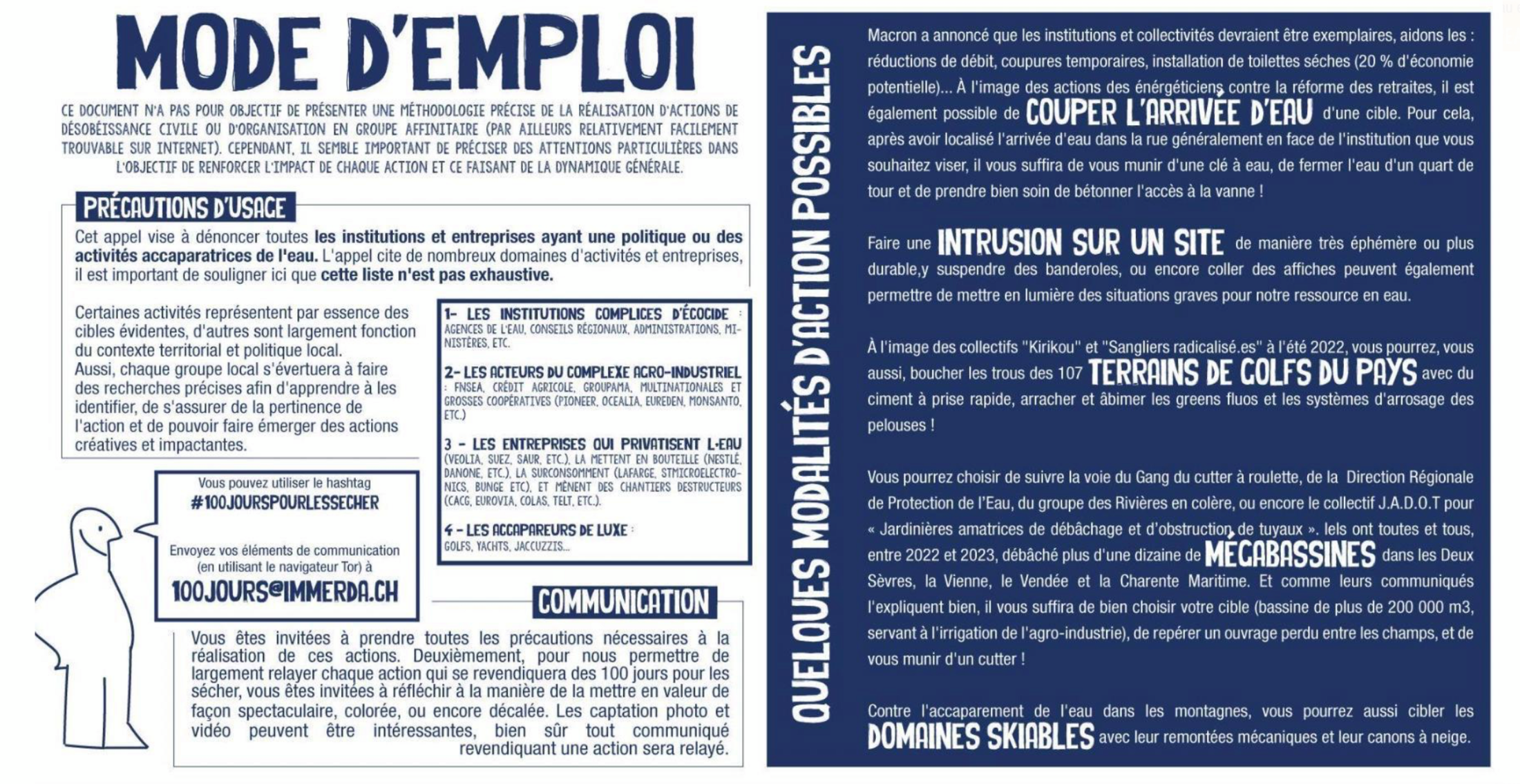

Meanwhile FDSEA 44 president Mickaël Trichet says he supported the dissolution of the SLT. “There was Sainte-Soline, the market gardeners and tomorrow it'll be something else,” he says. “Les Soulèvements de la Terre were calling for the draining of all structures [editor's note, irrigation reservoirs] and targeting the FNSEA - you think we're not going to say anything?” The SLT's campaign “100 days to dry them up” was a call to “directly target the institutions, the business and the infrastructure that hoard and poison water” and was designed to run from June 13th to September 21st.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

“There were workshops explaining how to dismantle an irrigation pump, how to cut a tarpaulin on an irrigation reservoir. And it's everywhere in France. You can see that there are attacks on these reservoirs just about everywhere,” says Sébastien Berger from the FNSEA federation in the Vienne.

The agricultural model at stake

In December 2018 the FNSEA and the young farmers group Les Jeunes Agriculteurs signed a “partnership agreement” with the minister of the interior at the time, Christophe Castaner, and the gendarmerie over “securing farms”. This accord, which has since been suspended by an administrative court, provided for the two unions to “communicate information” to the gendarmerie, and for a specialist unit, called Demeter, to protect the “agricultural domain” from “acts of an ideological nature”.

The bone of contention is the “agricultural model that we want” accepts Mickaël Trichet, who has personally had antispeciesist protesters on his livestock farm. “It's a question of scale, whether it's about water, the production model, livestock,” he says. “The fact we don't agree doesn't matter, but when you go onto farms, and start to dismantle equipment, that's not symbolic. You're going into someone's home. Entering someone's farm is unforgivable as far as I'm concerned.”

Yet as FNSEA leaders are forced to admit, their organisation also has a history of violent opposition, of clashes, of destruction and of sabotage. The historian Édouard Lynch, author of 'Insurrections paysanne' ('Peasant Rebellions') published by Vendémiaire in 2019, points out that the recent action in which lily-of-the-valley plants were ripped out at an large-scale market garden in the Nantes area was “in keeping with a tradition of what the FNSEA might have done, they have symbolically ripped up pine tree plantations to show that they didn't like that [agricultural] model”.

“I'm not saying that it's better to go and smash up a prefecture,” says Mickaël Trichet. “When people are really fed up things can get out of hand. In general when we take action it's because there's a crisis situation, and it's true that the people taking action today think that too. The only difference is that we attack the state, the institution. Afterwards, when we've set fire to a prefecture, I can guarantee to you that whoever is president of the organization, the federation, I guarantee that they pay. And those who've gone too far in their actions, in general they remember it because there are fines. And if it was once resolved in a minister's office, well that's all over and done with.”

What is different with the current clashes is their “radical nature”, Mickaël Trichet insists. “There's an ever-greater radicality, people are growing in power. We need to be careful.”

A former union official agrees that things are becoming more radical. “On both sides,” she adds. “The issue of reservoirs goes back 20 years. There are lots of farmers who don't think it's right to build reservoirs. The FNSEA has not gone through its environmental revolution and they won't do so with Arnaud Rousseau. It's easier to have a go at environmentalists who are a bit radical than to question yourself.” Laurence Marandola, spokesperson of the Confédération Paysanne, notes: “I fear this dissolution decision will make the violence worse. If the government and political decision-makers don't choose dialogue on environmental planning and about water, we'll carry on heading for disaster without coming up with any answers.”

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English article by Michael Streeter