Up to 1,000 cows kept under cover day and night, eating maize, soya and alfafa, each in the 10 square metres that will be its permanent home. A huge herd that will be milked three times a day, and produce up to 8.5 million litres of milk a year. While the slurry produced by the cows will be used to run the biggest methane power plant – 1.5 megawatts – yet built in France. A grotesque science fiction futuristic vision of the French countryside? Far from it; this is a detailed and current - if controversial - project to construct the biggest farm of its type ever built in France, deep in the countryside of Picardy, a northern region traditionally kown for its cereal crops, beetroot and beer.

This huge project, run by building group Ramery, is an encounter between two very different worlds; on the one hand the traditional activity of milk production, a symbol of the French countryside, and on the other, big industry and the culture of maximising profits. “If it's considered wrong to say that we are creating this farm to make money...” Michel Welter, who is running the scheme for Ramery, says ironically. Welter, himself a former dairy farmer, says: “The point is to keep added value here in this département. It's an all-embracing economic project. Can we afford to give up the economic resources and the inward flow of money that agriculture could provide?” With work already under way, the group hopes to start milking the first cows in ten months – in time for next summer – and to employ 15 people on a site where the buildings and tarmac will cover 7.5 hectares.

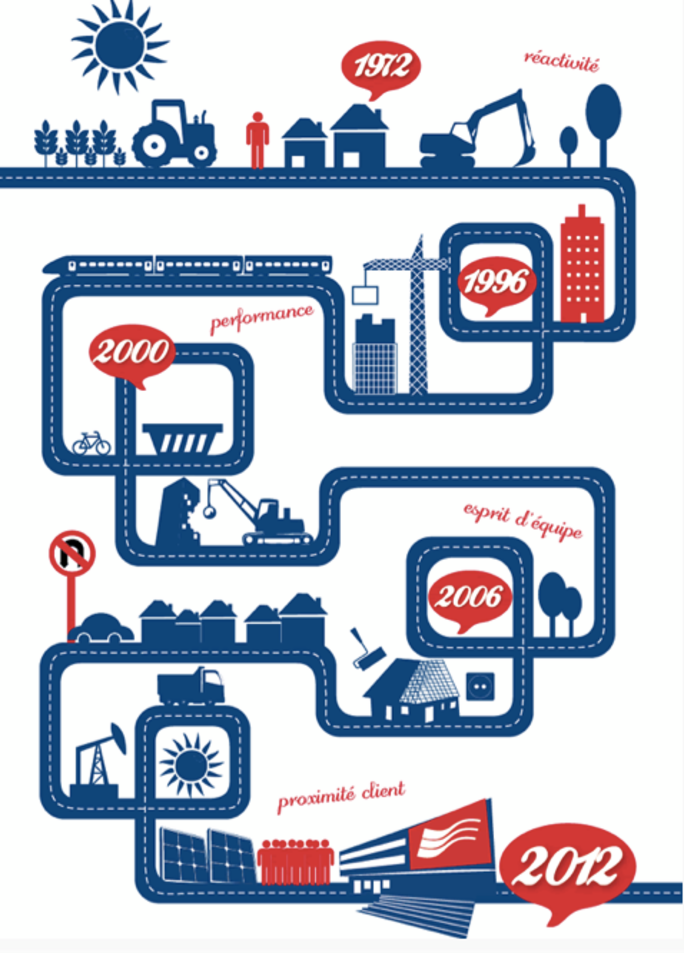

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The “thousand-cow farm” has certainly stirred up passions and divided opinion. An unprecedented coalition of neighbours, environmentalists and the environmental farming movement Confédération paysanne co-founded by anti-globalisation activist José Bové has attacked what it calls a “factory of a thousand cows” and the industrialisation of farming. “At the start I was not against it, it was going to provide work in the village,” says local doctor Michel Kfoury, president of the association formed to stop the farm, Novissen. But having studied the plans during the project's public inquiry he became worried about the health impact of keeping so many animals in one place, which could be dangerous during an outbreak of a serious disease, and of the number of lorries loading and unloading the slurry and green manure destined for the methane plant and local fields. “Forty percent of the area for spreading [the manure] is more than 25 kilometres from the farm centre,” he says.

The traffic linked to the dairy activity itself will involve around two lorries and 15 vans a day. Then there is the question of water. Pumping water from underground has been banned in some local areas in the past because of the excessive presence of pesticides. “That's what worries us the most,” says Michel Kfoury. Dairy cows drink a lot of water and 1,000 animals would get through around 40,0000 cubic metres a years. The environment agency the Autorité environnementale has stated: “The major issue of the project is the protection of the quality of surface-level and underground water with regard to the site of intensive farming.”

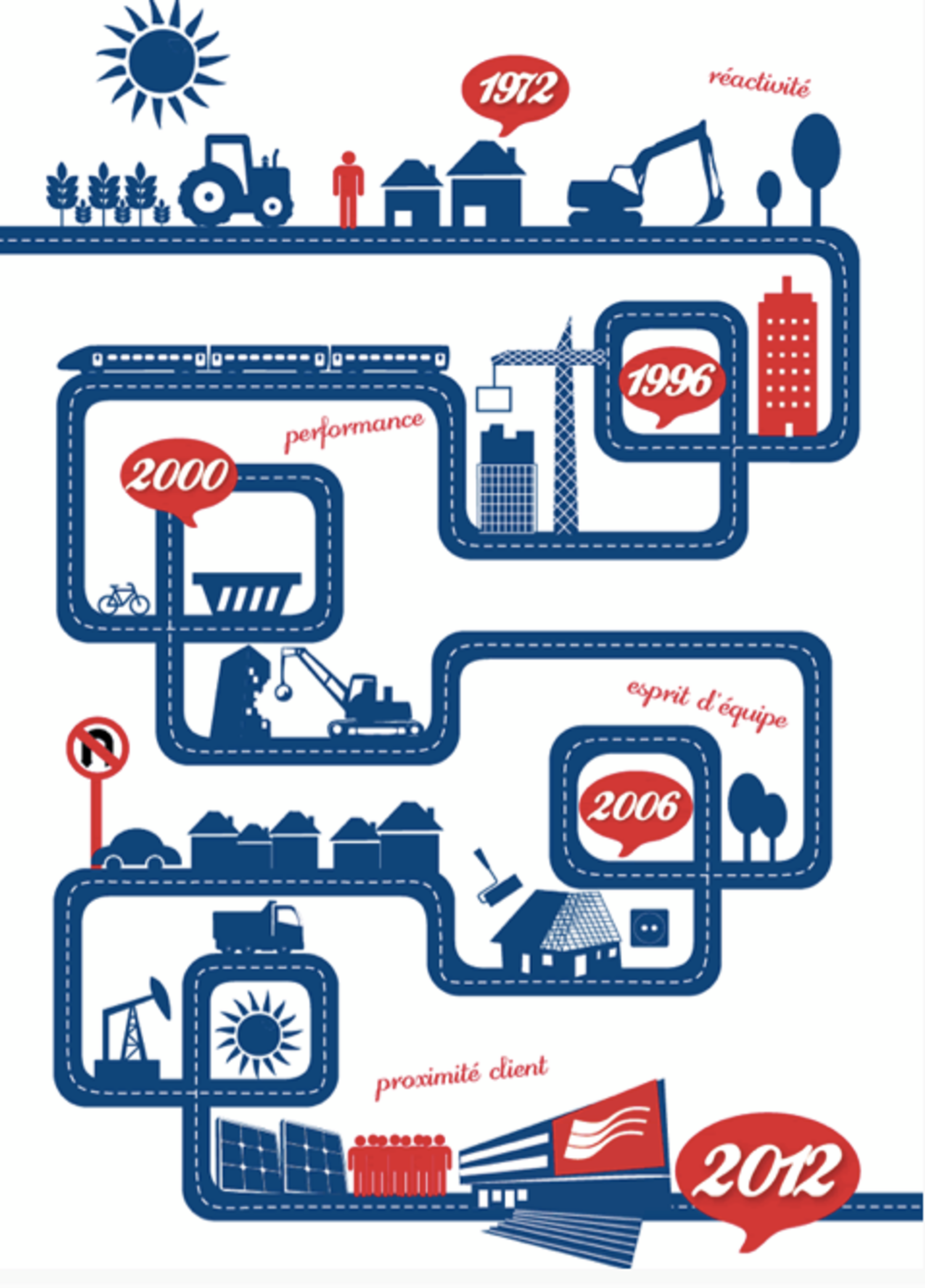

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Henri Gauret, the mayor of Drucat, a village of 900 inhabitants where the methane plant will be based, is worried that the plant will be just 600 metres from the nearest houses. “If there are bad smells, flies, insects, we'll get them,” he says. As for the Confédération paysanne, it wants to make the issue a national campaign as France decides how to implement the latest Common Agricultural Policy reforms agreed by the European Union in June. On September 12th protesters occupied the site of the planned farm, while other campaigners briefly occupied Ramery's offices at Erquinghem-Lys in the Nord département to the north. And last Saturday, September 28th, around 800 demonstrators turned up at the site to continue their protest.

Agriculture minister Stéphane Le Foll has given the project qualified support. While insisting that such initiatives are not a priority for the ministry, he told opponents in a letter that the plans “are based on innovative methods and technologies whose results, if they are borne out, could be employed in the context of collective projects”. A ministerial source said that provided the scheme stayed within legal guidelines it should be allowed to show what it can deliver, adding that small farms are not necessarily more environmentally-friendly than very large ones.

The section of the powerful farming union the FNSEA is clearly torn over the issue. “An entity that earns its money outside the world of agriculture developing a project based on its economic muscle and in which the farming partners are not the decision makers, is not the kind of set-up that we like,” says the union's local director François Magnier. However, the size of the project itself is “not a problem as such, it is not linked to mechanisation. The use of robots in milking parlours starts at 60 cows,” says Magnier.

Ramery itself is a major firm in the region, and has numerous public works contracts. In January 2012 its chief executive officer Philippe Beauchamps was put under formal investigation for alleged receipt of the proceeds of the misuse of company assets and for corruption over a loan of 4 million euros to Gervais Martel, the president of professional football club RC Lens.

'It's industrial exploitation of living things'

The farm project was bogged down in negotiations under the presidency of Nicolas Sarkozy but has re-emerged again after the election of President François Hollande – who was asked about it during his campaign in 2012. Delphine Batho, the environment minister sacked at the start of the summer, was largely opposed to it while she was in office. Her successor Philippe Martin has not yet made any pronouncements on the issue. The local prefect – the state's official representative in the département – did give the go ahead for the scheme in February 2013 but at the same time ruled that it should be limited to 500 cows, not 1,000. This was on the basis that the developers did not have at their disposal the extra 1,500 hectares needed to spread the manure produced by 1,000 animals.

Yet the farm that is now being built is indeed big enough to house 1,000 cows, in line with the formal planning permission granted in March of this year. Indeed, the Ramery group says openly that it has 3,000 hectares at its disposal, the amount needed to spread the manure for a 1,000-cow herd. “And looking at the commitments made by local farmers, if we needed it we'd have 5,000 hectares available,” says Michel Welter. In other words, enough for 1,700 animals. “The aim is still to build a farm for 1,000 cows,” confirms Welter, who says that the break even point for the venture is somewhere between 800 and 850 cows. “For a long time we've spoken of a plan for 999 cows, just as there are jeans for 9.99 euros,” he adds provocatively.

Several appeals have been made against the granting of planning permission and the official go-ahead given for the farm. A side issue to the story is that Éric Mouton, the mayor of Buigny-Saint-Maclou where the farm itself is based, is also the architect who conceived and drew up the plans. Is this a conflict of interest? Not according to the mayor. “I am not judge and jury, I didn't take part in the council vote,” he told Mediapart. The contract earned the mayor between 30,000 euros and 40,000 euros, even though he does not have any particular expertise in designing buildings for livestock.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

As for the Ramery group, it has not held back on lobbying in order to convince the authorities of the importance of the scheme. In 2011 the company took around 40 local mayors and departmental councillors plus other local dignitaries, including the sub-prefect, to visit a farm in Germany that milks 800 cows and also has a methane plant.

The Picardy scheme also shows that the countryside is not just a story of financial failures, rural desertification or despair. It has also become the target of significant investment by new players on the scene who are attracted by the potential financial returns in agribusiness. This is precisely what opponents fear. “This project removes the need for small-scale farmers and destroys agriculture,” says Pierre-Alain Prévost, the coordinator for the pro small farmers campaign Envie de paysans! on behalf of the Confédération paysanne. “It's no longer farming but industrial exploitation of living things, to the detriment of the environment, of biodiversity and of animal well-being.”

Critics say such farms are a form of land monopoly. “Ramery is in the process of concentrating all the livestock farming of the département: doing in the Somme what was done in Brittany with pigs [editor's note, where there is large-scale intensive pig rearing],” says Michel Kfoury from Novissen. But Michel Welter says it is pointless getting worked up about changes in the rural world. “Today half the UHT milk [in France] comes from Germany because it's cheaper,” he says. “We're in a European market. If we don't do all we can to reduce the cost of production, others will.”

Welter notes that from 1990 to the present day “the price of milk has not changed while the cost of fuel has gone up 4.5 times and labour costs by two”. He says the average cost of milk production is around 392 euros per cubic metre. But it is sold at between 330 and 340 euros per cubic metre, making current dairy farming unsustainable. “If I was able to earn 1,500 euros net a month with 30 dairy cows by working 70 hours a week I'd perhaps be happier,” he says. “But that's no longer possible. My parents had a herd of 25 cows and were able to bring up three children. With 25 cows I wouldn’t even be able to pay for my three daughters' studies.” Welter adds: “Dairy farmers are in the process of disappearing. It's a dog's life.” Between 2000 and 2010 a third of all dairy farms disappeared in the Picardy region alone.

François Magnier of the FDSEA farming union says there are concerns about the issue of animal husbandry when it comes to such large herds. “A herd of 1,000 cows, it's fundamentally different,” he insists. “When you have 70 you know them all, if there's one coughing you pick up on it. You milk them, look after them, you do everything. But you can't do that on you own with a thousand cows, there won't be the same personal attention.” However, the mayor of Buigny-Saint-Maclou, Éric Mouton, the farm's architect, says: “Everyone loves daisies but you have to move with the times, not stick with methods from another era.”

Pierre-Alain Prévost of the Confédération paysanne agrees that it's a “clash” of two economic models. “Where will we draw the line? At 1,000, 5,000, 20,000 or 50,000 cows?” Michel Welter does not seem fazed by the numbers. He has just returned from the United States where he visited Fair Oaks farm in Indiana which has 25,000 cows. Still amazed by what he saw, Welter describes the farm's public gallery where visitors can watch this vast herd being milked; just as if they were watching a show at the theatre.

------------------------------------------

English version by Michael Streeter.