“Stop humiliating us, stop policing us, stop executing violence on our bodies,” read a Tweet from Sana Saeed, a California-based writer and video film producer and anti-Islamophobia activist, who appeared to sum up the exasperation of many women around the world at the recent and growing number of bans on the wearing of the burkini on French beaches. “Stop being so insecure with your identity that you see our mere existence as a threat to yours,” Saeed added.

The bans have been introduced by 16 municipal authorities, mostly by conservative councils on the south-east Riviera coastline, including the city of Nice and the town of Cannes where in several incidents this week Muslim women wearing a headscarf and tunic, and not a burkini, have been asked to leave the beach or pay a fine.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

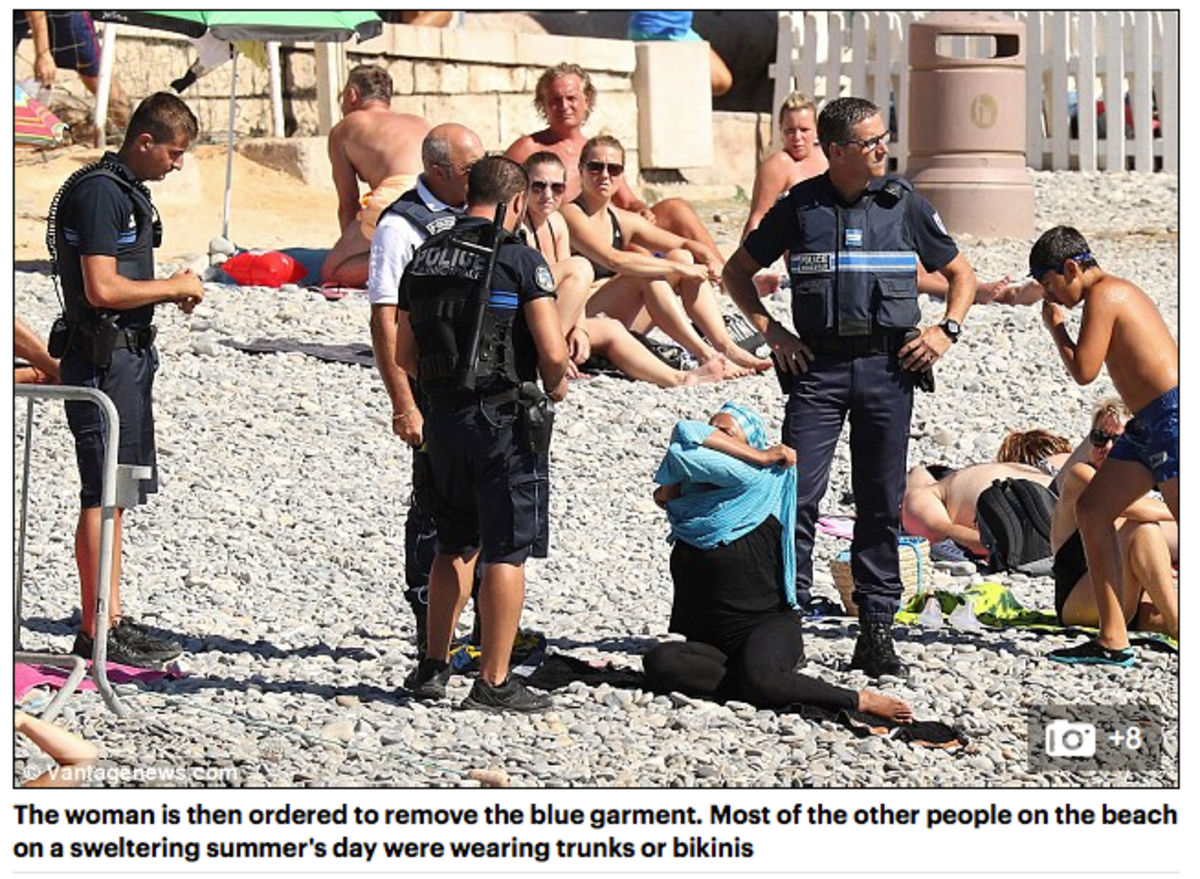

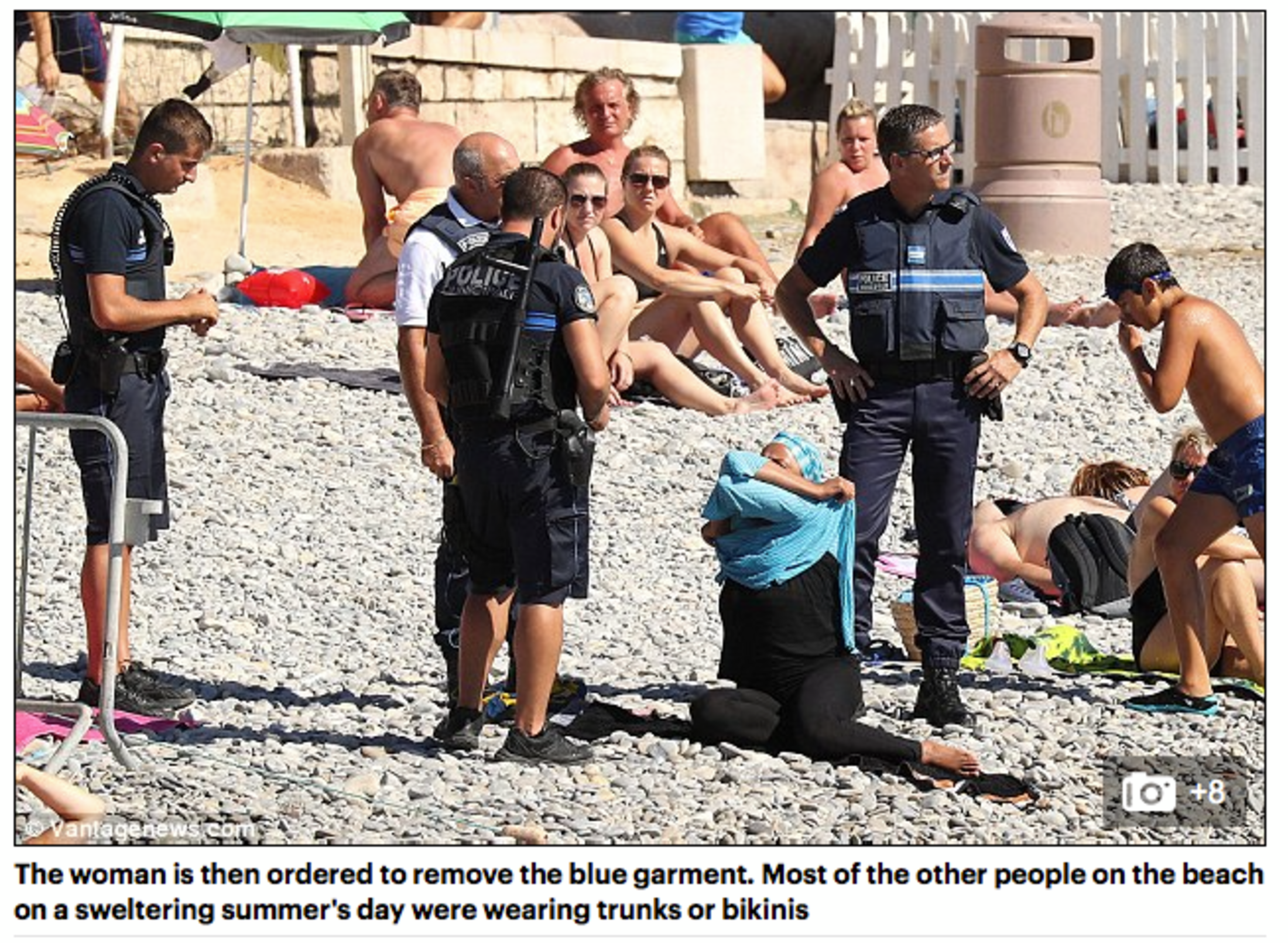

“Is humiliating women publicly part of the plan for liberating them?” asked US rabbi and author Rav Danya Ruttenberg in a Tweet on August 23rd after pictures (see one above) were published of one such incident in Nice. “How can one accept the public humiliation meted out to this headscarfed woman that the police force to undress?” Tweeted Widad Ketfi, a journalist with the online collective Bondy Blog, reacting to the same picture.

Feiza Ben Mohamed is spokeswoman for the Federation of Muslims of Southern France (Fédération des Musulmans du Sud is head) and she has begun posting videos of what she calls “the hunt for headscarfed women” on her social media accounts. “An absolute shame on the country,” she commented with one of the videos. “The police make a woman with a headscarf undress. I feel like throwing up.”

In an opinion article for Middle East Eye, Widad Ketfi wrote of the paradox of French politicians “who want Muslim women to hide their political opinions but to discover their bodies”. Describing the burkini as “swimwear which resembles a diving suit, worn by conservative women”, Ketfi argued it would never have become an issue “if the women weren’t Muslim”. The supporters of the burkini bans “don’t want to liberate Muslim women, they want to undress them because, in reality, the aim is not, and never was and never will be, to emancipate women but only to control their bodies”.

The word shameful is an apt description ofthis anti-burkini controversy that occupies the French public space since the beginning of August, and which gives an idea of the likely debates to come during campaigning for next year’s presidential elections; Shameful because the bans appear to be a reaction to the recent terrorist attacks that have bloodied France. It is as if there is link between the jihadist killings and the wearing of this swimsuit. Shameful also because it signals, once again, the French obsession, even the French state’s obsession, with Muslim women.

Everything that could have been said seems to have been so by angry editorialists, in the press and the social media, and notably in the Anglophone world where there was more enthusiasm to relay their analyses than in France. The inherent contradiction of the bans, thought up by over-50 white men in a position of power, is obvious. “There is something inherently head-spinning about the so-called burkini bans that are popping up in coastal France,” wrote Amandaz Taub, a former human rights lawyer who commentates foreign policy, in The New York Times. “The obviousness of the contradiction - imposing rules on what women can wear on the grounds that it’s wrong for women to have to obey rules about what women can wear - makes it clear that there must be something deeper going on.” This prohibition of the swimwear, which is a hand-me-down from France’s colonial past, is not intended to protect women from the patriarchy, argues Taub.

Prime Minister Manuel Valls called the burkini “the translation of a political project, of a counter society, notably founded on the enslavement of women” and which, as such, “is not compatible with the values of France and the republic”. But in fact the object is quite different, and that is to give the non-Muslim majority in France the sentiment that they can be protected in a country in transformation which refuses to see itself as it is – that is, culturally, racially and religiously diverse.

This fear, created by a perceived danger to French ‘identity’, is the subject of recurrent cleavages which are almost systematically fixated – in another specifically French phenomenon - with Muslim women. While this female population is most often relegated to the subordinate ranks of society, it supposedly carries a danger within. While these women are often confined to cleaning jobs, at night, or work as home helps, when they are not forced to stay at home because of the discriminations to which they fall victim, they are presented as a blotch to the definition of what it is to be French. It is striking to see that they are called upon to show “discretion” according to the term employed by Jean-Pierre Chevènement, head of the Foundation for Islam in France, at the very same moment that this invisibility is beginning to be questioned by the young women born in France to immigrant families and who claim for themselves the multiple ways in which to practice Islam, and sometimes the wearing of the headscarf as a symbol of their heritage.

The burkini is indeed just the ultimate example of this stigmatization which in recent history has targeted, among other things, the headscarf. Stigmatised in schools, where it has been banned since 2004, in universities – where conservative Nicolas Sarkozy and socialist prime minister Manuel Valls agree that it is urgent to introduce a prohibition. But also in private companies, where every case that goes to an industrial tribunal causes a storm of controversy, and also on school trips, where accompanying mothers in headscarves run the risk of being prevented from joining excursions. Some school heads have openly questioned the wearing of “long black dresses”, while the full, face-hiding veil has been banned from public spaces since 2010.

David Thomson: 'For Islamic State, it's a godsend'

Muslim women wearers of the burkini have not been given a voice, as was the case for Muslim women in previous debates. What are their reasons for wearing the swimsuit? What consequences does that decision have on their lives? They have until now remained inaudible, and the appeals for interviews launched here and there by some media appear as a tardy admission of a silence that has become deafening. The question of the uses made of the burkini has even slipped into the background. What is its history behind the current apparition of the garment? The numerous studies on the subject by anthropologists and sociologists have hardly been mentioned.

Linguist Marie-Anne Paveau sees here what she calls the “ventriloquist statement”, or answering in the place of others. This mechanism, she says, “currently flourishes in French politics and the media”.

“This enunciative form particularly targets usually minoritised, even stigmatised, and sometimes vulnerable, individuals – women, racialised individuals, Muslims,” she said. “And it is, unsurprisingly, mostly adopted by the dominant, non-racialised, non-stigmatised who do not belong to visible or invisible minorities.”

Once more, Muslim women are not pointed at because of their thoughts or attitudes (the woman on the beach in Nice appeared to be dozing when the police arrived), but because of their bodies. What is normally generally considered to be an intimate issue, their choice of dress has become a national political issue, and accused of being a problem that, variously, calls into question the “values of the republic” or “public order”. All of this is not new. During colonial times, the French state constantly went about unveiling “indigenous women”. In an article published on the website Contre-attaque(s) before the burkini controversy, Zhor Firar, a commentator and activist on questions of Islamophobia and the place of women in islam, detailed this “long French history”. She cited the role played by an association created by the wives of French generals Raoul Salan and Jacques Massu during the Algerian war of independence, when a public “unveiling” was organised against women in Algiers in May 1958. “Unveil in order to better reign and above all control consciences, this colonial weapon was deployed in the Algerian war to impose a civilizing model,” wrote Firar, who noted that several “ceremonies” followed demonstrations initiated by the French army.

Firar quotes from US historian Jennifer Anne Boittin, an associate professor of French, francophone studies, and history at Pennsylvania State University, who wrote about the unveilings in an essay published in the review Gender & History. “On each occasion one could see an almost identical, and theatrical, staging: groups of veiled women paraded along to places which were traditionally dedicated to official ceremonies (central squares, town halls, war memorials),” wrote Boittin (1). “After arriving, a delegation of young women, in European dress or wearing the haïk (a traditional Algerian veil), shared the stage or the balcony with the generals and dignitaries present, clutching bunches of flowers, and delivering long speeches in favour of the emancipation of women before throwing their veils into the crowd.”

In her article, Zhor Firar concluded: “Through these unveilings, colonialism practiced a policy of humiliation, in order to show its supremacy over the Orient, which was designated as barbarian.” She noted how the “unveiling” ceremonies were often followed by “re-veiling” campaigns, which the French Caribbean philosopher and psychiatrist described as a show of resistance.

This French obsession is saluted by the propaganda of the Islamic State group. In its review Dar-al-Islam, the jihadist group rejoices that France is no longer a “grey zone”, meaning that the country had become a place where Islam and secularism had now become incompatible. David Thomson is a French journalist with Radio France Internationale and who is a recognised specialist on jihadist movements. Questioned by France Info radio station about the cases of Muslim women intercepted by police on Riviera beaches this month, he said that jihadists “appear to be themselves surprised that the municipal police in Nice are doing their propaganda work in their place”.

“For them, it’s a godsend,” said Thomson. “The jihadist narrative has been hammering out for years that it will be impossible for a Muslim to live their religion with dignity in France. However, at the beginning of the controversy over the burkini, the jihadists and salafists were surprised at all the racket made by the ‘miscreants’ on the subject of the wearing of clothing that they themselves judge to be contrary to their dogma.”

Given the scale of the controversy, it would appear that those who caused it see an interest in fuelling it further. None of those who defend the bans have been upfront with their ideas. Far from envisaging the violations of individual freedoms caused by the bans, the mayors who introduced them pretend to act in the interests of the Muslim women targetted.

According to Stéphanie Hennette-Vauchez, a jurist and head of the Centre for Research and Studies on Fundamental Rights (part of the University of Paris-Ouest-Nanterre-La Défense), the claims by the mayors that the bans are justified because they defend the “values of the republic” and “public order” simply do not stand up, even though they were validated in the first instance by local administrative courts. Writing in her blog on the website of French daily Libération, she argues that to link the threat to public order to the context of the recent terrist attacks is “dangerous”. Not only because this in practice encroaches fundamental rights, but also on a technical legal level because a threat to security must be documented, which is not the case in the recorded incidents. The principle of secularity, she writes, “cannot be read as generating a requirement for religious neutrality on the part of private individuals in the public space”.

The events could be regarded as grotesque if it were not for the gravity of the situation: a group of mayors, who have no legislative powers, are preparing the way for new national prohibitions. Municipal police are not sociologists able to distinguish between one use of clothing and another, as their interceptions of Muslim women with headscarves demonstrates. The role they have been given to police morals places them in an untenable legal, political and human situation. The question now is whether the Council of State, which is due to announce its ruling on the validity of the bans on Friday, will make the mayors see reason.

1: The quotes from Jennifer Anne Boittin's essay cited in English here are a translation from French and may vary slightly with her original text in English.

-------------------------

The French version of this article can be found here. See also Mediapart editor-in-chief Edwy Plenel's analysis of the "burkini ban" controversy here.

English version by Graham Tearse