It is a leafy and well-off village in rural Essex between London and the university city of Cambridge, and the kind of quiet, well-heeled place that many English people aspire to live in.

Widdington, with its population of around 500, and where the average inhabitant is a millionaire, is a village where people retire on their private pensions when they reach their fifties and play golf, tend their gardens, dabble in the markets, help support the creation of start-up companies, go to the pub and socialise.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The fortunate residents of Widdington are thus rarely short of things to do.

Yet, over the last three years, one issue has been gnawing away at this idyllic corner of rural England: Brexit. Usually this village - and the wider Parliamentary constituency of Saffron Walden - is staunchly Conservative, with that party's candidate picking up more than 50% of the votes. Traditionally the Tory candidate beats their nearest rival – usually a Liberal Democrat – by 20,000 votes (out of 60,000 voters). But the usual order of things was first shaken up in the 2015 general election when the UK Independence party (UKIP) came second and then again in 2017 when Labour were the runners up.

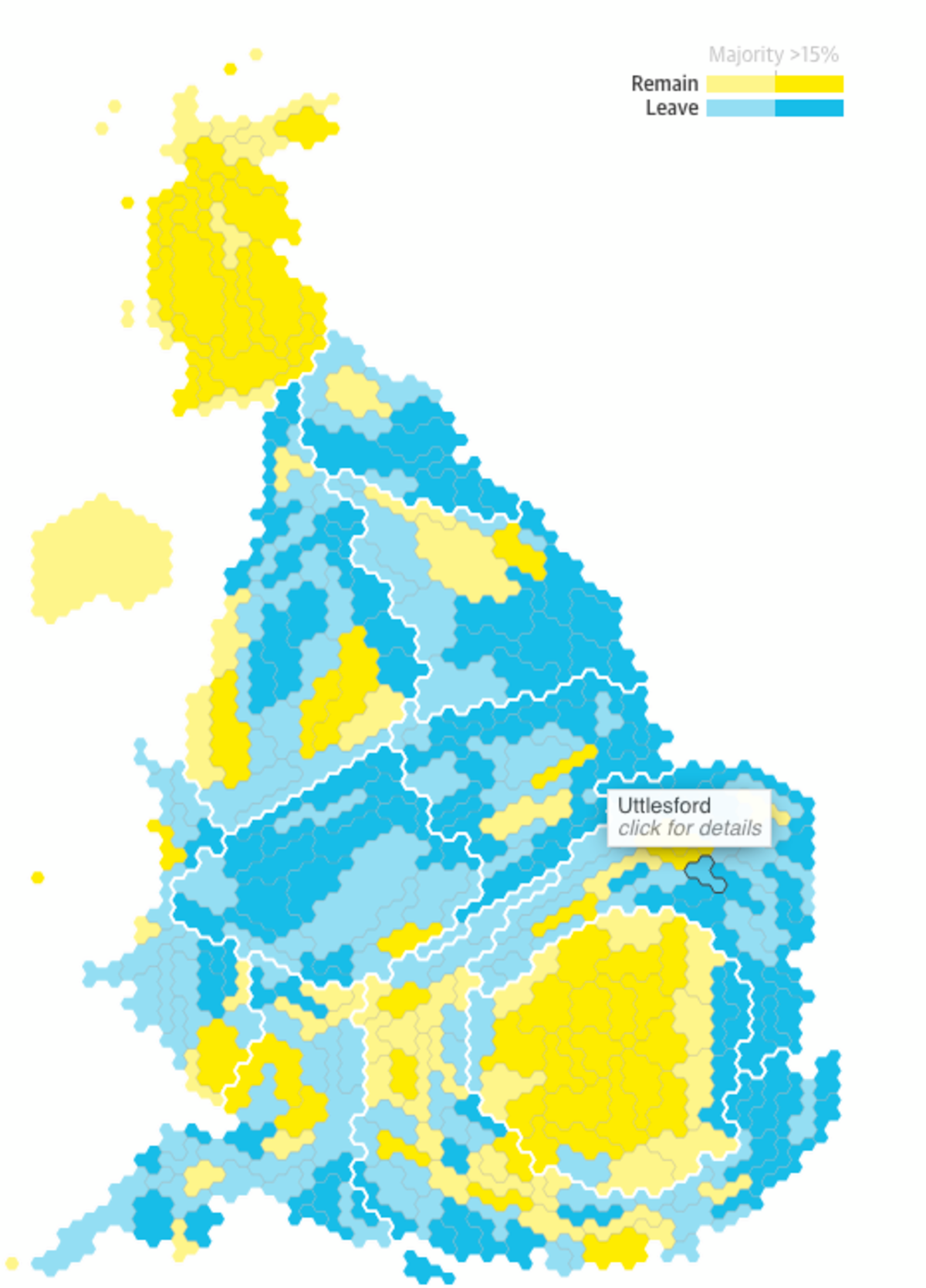

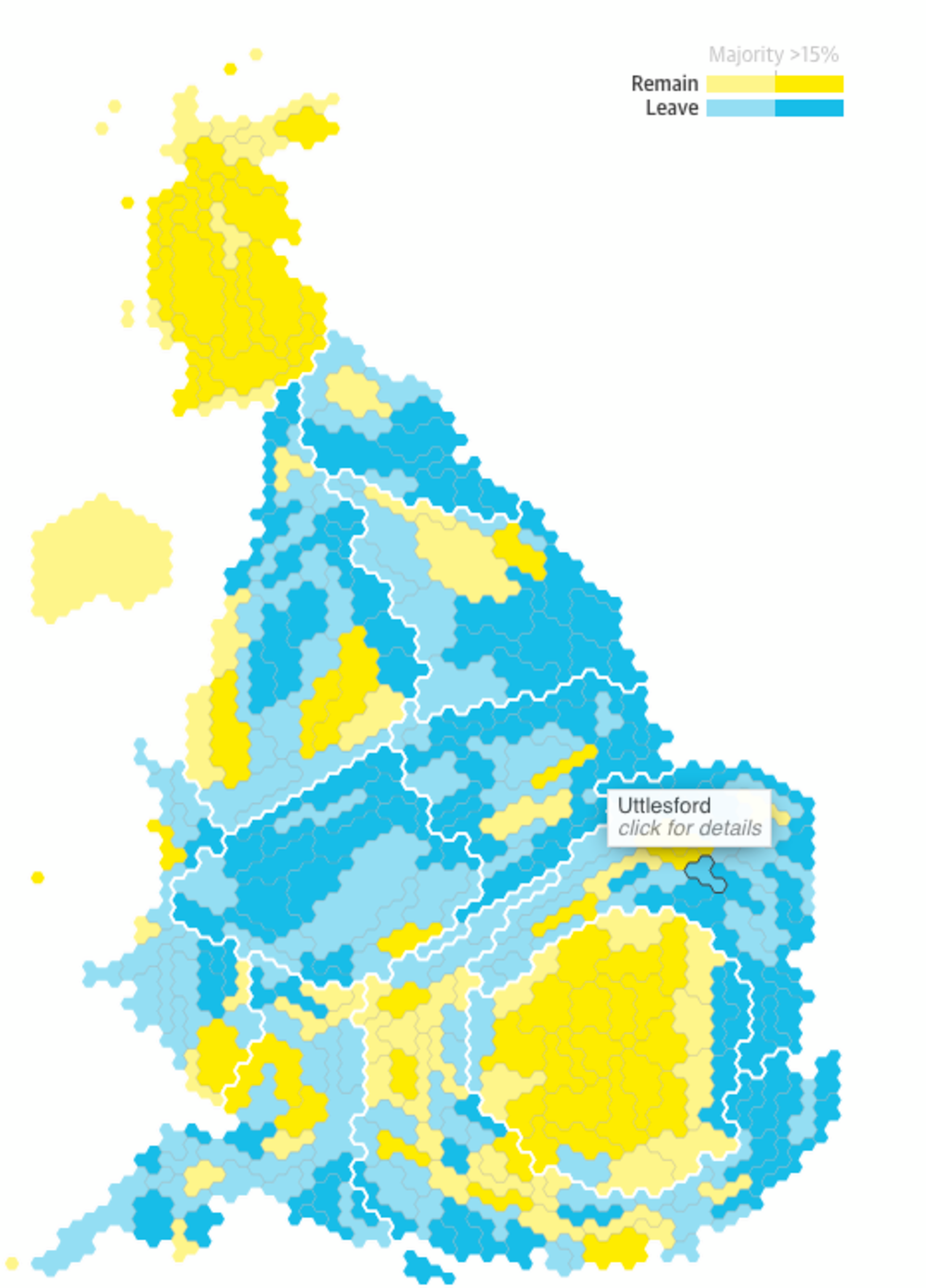

But these events were as nothing compared with the alarming and almost exactly 50-50 split in the way that the people in the Uttlesford district, which includes Widdington, voted in the referendum held on June 23rd 2016 on whether to leave the European Union. Here, 50.58% of voters opted to leave the EU while 49.32% were in favour of remaining. Widdington found itself a village split down the middle in the heart of a divided England inside a fractured United Kingdom.

Will Jennings, a professor of political science at the University of Southampton, who knows the electoral map of the country well, told Mediapart before our trip: “You'll be going to a semi-rural constituency in the centre of England that's been tempted by a return to insularity in a world that has never been so mixed up - taking refuge in historical stereotypes stems from apprehension in the face of social change. However, as the country has no culture of referendums (the first and virtually the only one dates back to 1975 on the issue of whether to stay in the Common Market) the consequences that this kind of consultation might have were not anticipated - especially as it coincided with the populism that Europe and the world is experiencing. This meant a fragmentation of the vote that broke up the traditional bipartisan vote, to the point where it is still causing general concern...”

To get a feel for a place there is nothing like going to one of the main sources of local information. First stop, then, was Kristin, aged 63, a woman of common sense whom many in the village rather look down their noses at – while insisting they mean no harm – and who is considered to be the village gossip and an archetypal reader of the Daily Mail, a Brexit-supporting tabloid newspaper. Kristin, who is not very well-off and is worried about her old bulldog, welcomes Mediapart into her cottage. She and her husband have a collection of standard bric-a-brac, ranging from a poster for the film Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot, near the loo, to the neck and head of a plastic ostrich which takes centre stage on one wall of the living room.

Kristin mentions Sir Winston Churchill and his much-quoted observation that if Britain had to choose between Europe and the “open seas” then it must always opt for the latter. With a look of distaste, she sets out the reasons behind her decision to vote for Brexit. “I could no longer bear being dictated to about what I must do by people who've never set foot here. And I'd had enough of where the country was heading,” she says. There follows a whole litany of complaints in which no one is spared, especially Tony Blair who is invariably described as a “war criminal” (because of the Iraq War). Above all, Kristin heaps scorn on the country's Members of Parliament (MPs). She has still not forgiven them over the infamous expenses scandal that broke in 2009. She suspects they are clinging on to their positions so they get a good pension, while the country itself goes to the dogs.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

“We had the best justice system on Earth, which was the envy of the world,” she says sadly. “Same for the post office. It's all gone. There's no more pride or fairness in this lousy country. Look at the privatisation of the railways, which has led to no improvement for the rail users as, before anything else, they have to enrich the shareholders.” The name of Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn crops up. “It's impossible to trust him: he supported the IRA. I escaped seven Irish terrorist attacks when I worked in London; one bomb exploded half-an-hour after I'd gone down Oxford Street; and I heard the explosion of another from a few hundred metres away.”

Kristin attacks what she calls the “lack of democracy and leadership”. And she says she has become disoriented politically. “I don't think I'll vote in the European elections, or perhaps afterwards. Not voting is a waste; but voting itself is a waste of time. I feel both an enormous anger and enormous apathy. No one listens to us and soon we won't listen to anyone. In Widdington Brexit has divided whole families. I speak to everyone, but not about that.”

For example, one of Kristin's friends, Cathie, voted to stay in the EU. They still have plenty to talk about but the two friends never speak about “that”. Cathie does not speak about “that” with her husband either, but in their case they are not on great terms as a result of the vote. Indeed, after 36 years of harmonious marriage they are now at daggers drawn, and have even gone weeks without saying a word to one another. Cathie, a former police officer in London, pointedly shows Mediapart into a distant room in the house, a resolute look on her face. Her back seems to send a hostile message to her husband who is left trailing in her wake. Then the husband, who has just retired as a superintendent in the police, comes and has a quick peek though the window on the pretext of doing something in the garden.

“He hesitated until the last minute,” says Cathie, clenching her jaw, “before, on a sudden impulse, saying he was in favour of Brexit. He didn't even consider the disastrous consequences for my mother who's lived in Avranches in Normandy [editor's note in northern France] for 20 years. She became a French citizen in December to ease her anxiety. At least she can claim to have a plan B! I don't know how the United Kingdom itself is going to get out of it. A second referendum wouldn't resolve anything because we're so divided and in the worst way: 50-50.”

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Cathie does not spare the European Commission from her criticism either, which she says failed to concede anything to British prime minister David Cameron, who before the referendum had sought to win concessions from Brussels over Britain's membership. Instead he came away empty handed and had to trigger the referendum – believing, however, that the 'remain' side would win easily. But it all fell apart. The result, says Cathie, is that: “Direct democracy, or supposed direct democracy, is in the process of destroying representative democracy. Propaganda is winning and what we are seeing, and this is one of the symptoms of this political tragedy, is the sloganisation of political life. People violently yell out empty phrases. Following on from Theresa May the country repeats 'Brexit is Brexit'. Why not 'cheese is cheese' while we're at it?”

Cathie is an eloquent example of the quality of recruitment carried out by the British police, who have for a long time been trained in how to have a dialogue with people rather than resorting to the baton. She is not really on the Left, and has indeed always voted for the Conservatives with the exception of the occasional detour to the Liberal Democrats. However, for her the value of democracy is in that quality which gives it its richness – debate. “One day,” she says in a serious tone, “we'll have to come back over the language which has led us all by the nose. The very creation and systematic use of the word 'Brexit' has been a brilliant but awful discovery, a discovery that has imposed itself in the public mind, making the thing itself inevitable and unquestionable. What a magical neologism: Brexit! It's no longer about politics but sorcery. I'm horrified.”

'Like a monkey trapped in a spaceship'

Kev, a talented engineer who went to the best schools and universities in the country thanks to a system of grants helping the most promising youngsters from underprivileged backgrounds, opens his door, his hair unkempt. He welcomes Mediapart into his large house where all the machines, from the washing machine to the coffee machine, show signs of apparent distress with their lights constantly flashing. He offers a large glass of Spanish wine - “I'm sorry I don't like French wine” - and says: “We're going through a form of civil war in a country that is almost as divided as during the ban on fox hunting under Tony Blair in 2004, but over a much more fundamental issue: when 1% of the population earns more than 65% of the citizens the situation is bound to be revolutionary. And, because the system comes up with ruses and distractions in order to avoid revolutions, we offered an unhappy public the chance to push like mad on all the possible buttons, like a monkey trapped in a spaceship!”

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Kev continues: “In the United States of America, this gave us Trump. In the United Kingdom, in the same year, 2016, you had the Brexit referendum. Yet the referendum is a tool which requires certain political logic, as it's treated as irrevocable. It needs to have a set majority that makes it acceptable for everyone. As 5% of the electorate are liable to change their mind, a margin of 10% is thus required: as a result a referendum that can't be disputed must be won by at least 60% of the voters. Over the years the people change and votes alter, which is why there are democratic consultations. To hang on permanently, to say that we're there forever, is contrary to democracy. Otherwise all you'd have to do is to decree at each general election that you are sticking with the result of the previous election!”

Kev is not in any way a Labour supporter. He considers Jeremy Corbyn to be a perpetual opponent who is unable to formulate any policies and who is thus unfit to govern. He is a liberal democrat and classifies his fellow humans in three categories: those who give the orders, those who obey them and those with non-conformist spirits. He voted to remain in the EU despite the mistrust he feels for the bureaucracy in Brussels, which he compares to those bureaucracies which corrupt, as he sees it, the governing authorities in football, Formula 1 racing, the Olympic Committee in Lausanne and Red Cross International in Geneva, a large portion of whose budget is swallowed by its bureaucracy rather than being used to save lives, he says.

“Staying inside the EU has obvious advantages,” mutters Kev. “The United Kingdom uses the new universal language which in the past we called – sorry to rub salt into French wounds! - the lingua franca. That gives us an unassailable position from which to penetrate the European market. The Japanese set up their car factories here for that reason: they will take them away if they have just the British market and not the continent.”

Enlargement : Illustration 6

That evening in the pub in Widdington, which bears the name 'Fleur de lys' – a design that is associated with the French monarchy – Kev takes part in the quiz that the landlord holds every Thursday evening. Sitting with a group of close friends, who no doubt have contradictory opinions, Kev is no longer the same man as he was earlier. An elusive irony has replaced the unshakable convictions. He laughs at everything rather than makes pronouncements. The English have mental shock absorbers and are able to avoid bumping in to each other like fish in an aquarium. Some pubs in the country still have the old signs stating: “No politics or religion”.

We meet Arthur, a man who considers himself to be wise and level-headed. He voted to remain but admits: “I've never discussed it with anyone in the village. Even with my best friend and golf partner. We don't have a tradition of intellectual debate and we are keeping the anger because people's arguments are not up to the mark. And our democracy, which has been taken for granted for so long, has never seemed so fragile and is threatened to the extent that it no longer seems now unbreakable.”

The political divide is, in Arthur 's view, a new one: one which is not about class division or partisan commitment, even if there are anti-European traits that are peculiar to the different parties. “On the Right they look down on Europe as a continent adrift which the United Kingdom, with all its great power, has always saved from its demons, from Napoleon to Hitler. On the Left they have a profound disgust that comes from the common market, because of the hated noun 'market'! What is new is that the debate is monopolised by a far right that is pathologically opposed to Europe. The politician Jacob Rees-Mogg is the incarnation of this. His simplistic slogans such as 'let's take back control' have contaminated all citizens who are now convinced that every law voted on by the Parliament in London was imposed on them by Brussels!”

Enlargement : Illustration 7

Arthur says he is profoundly convinced of what Europe has contributed culturally and economically to his fellow countrymen, in a world where he thinks only common political action has a future. He hesitates and then says: “Here you are among the educated people of Brexit, who are just looking at the first chance to profit from it. They've succeeded in convincing the poor workers that the bureaucratic tentacles of Brussels had to be smashed, that they had to free the British market. What they in fact want to liberate is the right to exploit their fellow beings without any hindrance. And the working class, or at least that which remains of it, will realise quite quickly, under the yoke of these new feudal lords of the 21st century, that they are going to cruelly miss European social protection laws. The experts who are today vilified will be called in, too late, to the rescue!”

With England caught up in Brexit confusion, many of the old certainties have gone out of the window. The gentry now talk in Marxist overtones and the generation divide is not always evident. That can be seen at a house on the edge of the village where Fiona and Nigel live with their 20-year-old daughter Katherine. She has a twin brother and it is only during this unusual political conversation with a French journalist that she learns that he favours Brexit.

The mother, Fiona, voted in favour of remaining in the EU in order to maintain Britain's allies at a time when the world has become global and alarming. She thinks that politicians in their bubble, who come from the best private and public schools and who do not know what ordinary people in the street think, have been playing Russian roulette with the nation. “We're isolated in a country broken in two. On top of that there are some centrifugal forces as Scotland and Northern Ireland risk heading off,” she says. The father, Nigel, who voted to leave, plays down this risk of secession, says there is nothing new in this, and that Scotland, Wales and even the Cornish have always had independence movements which have attracted their share of cranks.

Their daughter Katherine did not vote as she had not reached the legal voting age of 18 in June 2016. At the time she would have voted in favour of staying but would today vote to leave “out of respect for democracy as it's the people's choice”. She thinks a second referendum would be a betrayal of this popular will by trying to force the electorate at the ballot box, like a parent who keeps on at their child until they give way: “Are you going to eat this cake?”. Her mother and father smile at this image while insisting that a population is not fixed but is dynamic and that a referendum result cannot be preserved forever.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

Her mother, Fiona, gives her perspective: “It might seem like I'm insulting the intelligence of the electorate who voted to leave but we didn't know what was waiting for us. You can't base the future on ignorance. We need experts who are able to enlighten us, even if we live in an era which rejects them in the name of hating the elites!” Katherine, however, refuses to get upset over what has been done. Looking ahead, she favours leaving the EU without a deal. “We'll suffer for three years but we'll come out of it big and strong after a decade,” she says. Her father, Nigel, is focussed on the problems of the present day. “We're trapped, especially with the Northern Ireland backstop. We're paying the price of the punitive hard-line approach of Brussels who want to make an example of us, to head off those on the continent who have a desire to imitate us!”

Will they vote in the European elections, currently scheduled for May 23rd? The family hesitates and Fiona is the first to speak. “I'll go and put a ballot paper in the box. So I don't betray the victory that was earned in 1918 when women finally won the right to vote in this country. And also so as not to leave the way open to the British far right, which is particularly mobilised ahead of that vote.”

'Pockets of violence ready to explode'

Sir John Curtice, who is the UK's most revered electoral analyst and is professor of politics at the University of Strathclyde in Scotland, summed up the situation to Mediapart: “The sovereignists who come from the conservative upper middle classes have forged a link with the social outcasts of the working classes. All share the same view of a European project that has failed, with which they have never had an emotional tie. England hasn't been invaded by a foreign power since 1066 and glories in having resisted Hitler alone in 1940. So this country therefore has a view of its place in history, of history itself and the lessons to be drawn from it which are completely different from other European nations. Add to that a geographical mentality and psychology which sees Australia as being on its doorstep – well before it considers France – then you understand why Europe has never dislodged the Commonwealth in people's minds in the kingdom.”

Enlargement : Illustration 9

Back in Widdington we meet Chris, 55, a businessman who has been retired for three years and who has lost 15 kilos ready to take part in the New York marathon. He continues to travel with his family and has photos of his safari trips in his vast kitchen. Chris, who comes from a Labour background, realised something was changing in relation to Europe in 1992 during the debates over the Maastricht Treaty. He came to the conclusion that the country needed to stop going down this cul-de-sac, even if the start of the European project, which began with just six countries, had been more appealing. Does Chris feel European? “Not at all. I've no desire to be associated with the continent. I live on an island. I feel English first of all, then linked to the Commonwealth. Europe for me is no more than a barrier, which stops Indian nurses or doctors capable of speaking our language from coming over rather than giving priority to nationals from East Europe.”

He does not worry about coming across as gung-ho. “I don't believe in the catastrophic scenario about a shortage of basic produce blocked at the border: we've survived a continental blockade by Napoleon and more recently one by French farmers! We'll bring in food and medicine by plane from America, Africa and Asia. I'm sure some solutions have been planned. We are doubtless much further advanced that we are letting on in this game of Brussels poker.”

As far as Chris is concerned the only way to leave is to make a clean break without getting trapped in a customs union. “Alongside the clown Boris Johnson and Torquemada Jacob Rees-Mogg, who are monopolising the stage, we Brexit supporters can count on good, more discreet and above all more solid politicians such as Sajid Javid – I hope I haven't got his name wrong – who is Home Secretary. Or Michael Gove who's in charge of the environment.”

Chris is unhappy at the mention of a second referendum. “That would inflame the country, at least the north, which suffers from terrible mass unemployment and won't let its victory in June 2016 be stolen. We don't have a revolutionary tradition like in France but there are pockets of violence ready to explode, in particular in the town of Harlow, a few miles from here.”

Enlargement : Illustration 10

In Widdington, as everywhere in the centre and south of wealthy England, Brexit supporters happily talk on behalf of the poor starving people of the north. That's true of Matthew, nicknamed “The Viking”. He says: “I worked in Doncaster between Sheffield and Leeds. I saw the ravages of de-industrialisation, communities reduced to nothing. But over time as a head of a business (I was running depots for DHL, UPS etc) I saw some English workers who were more used to being strikers than competitive. The arrival of manual workers from Eastern Europe who stuck to their task and were reliable did not make the British working class racist – they were that already. They didn't take on any person of colour as the unions, which controlled the hiring, were run by white supremacists (there's no others word). On the other hand, this working class did become anti-European, accusing the Polish and Romanians of coming and taking their work with the blessing of Brussels. So I knew that English workers would vote for Brexit.”

Matthew continues: “As for me, if I voted Brexit it was not for racist reasons even if I an convinced there is a real phenomenon of saturation and that inter-European mobility should have been controlled more. France is just a place of transit to England, you can't realise what we are experiencing as your pull of attraction is less than ours! And I didn't vote Brexit because I feel excluded or abandoned, I am financially very comfortable. I just simply can't take any more of Brussels which seems to me corrupt to the core. My mother was half Dutch and my father too, and moreover the other half was German, and my first wife was Danish. I am European even if I far prefer Northern Europe to Southern Europe. But above all I feel English. And an Englishman considers his home to be his castle, ready to activate the portcullis and drawbridge. Yet as far as I can see Europe is forcing us to open our doors forever. We have a last chance to close them before it's too late.”

John, who is in his 70s and who opted in favour of Brexit, welcomes Mediapart onto his veranda which looks out on a magnificent garden full of exotic plants, as if a hint of the Indies - but without the dust and heat - was wafting over Widdington on this April morning. John, who says he read up a lot and voted as a consequence of that, and who is a collector of old and fast cars, is clear about his views, which are delivered in a patrician accent. Suddenly he speaks with chilling softness: “I think I'm going to have to kill it one day, that one...” John has just seen a fox prowling near his geese. He then resumes his theme: “An Englishman doesn't like to be mistreated even if – and perhaps because – he has been constantly abused in their youth. I still remember the initiation rituals in my private school. In the end, that continued all my adult life with this club of Brussels bureaucrats who are responsible to no one and who aim to put us all through their blender: all peoples must be levelled out to become identical!”

Enlargement : Illustration 11

When speaking John contains his indignation, but occasionally lifts an eyebrow, his way of showing turbulence inside. “I believe in the strength that difference brings. You don't compose music with just one note. To take a more concrete example, during my life I've had a number of Italian cars and I can assure you that they have personalities! I value harmony but definitely not sameness. So I balk at [EU Brexit negotiator Michel] Barnier who lectures us, who refuses to change anything in the [withdrawal] treaty having made Theresa May cough up rather than negotiate with her. Ireland and the backstop? I prefer to joke about it: let's build a wall and make Dublin pay for it!”

More seriously, but still delivered in his deadpan style, John says: “I'm captivated by this period of transition. Europe has got out of control and must change. Our exit is going to push them to change. You'll never be able to thank us enough for what we have done! [The Duke of] Wellington put an end to Napoleonic Europe and its astonishing excesses and Brexit is stopping at the right time [Commission president Jean-Claude] Juncker's Europe and its unpleasant abuses. This Europe cuts us off from the rest of the world and in particular from Africa. Yes, we love others, the open sea, but not the Brussels system that deprives us of it and shuts us off. Those who are fighting for Brexit have a noble spirit, a taste for risk and movement: in contrast to those weaklings who hide away in their holes so that nothing changes.”

John, who reveals a steely conviction about what he says, continues: “I want you to rediscover democracy which must be local. I regularly meet the Conservative MP for our constituency, Kemi Badenoch. She's a black woman of Nigerian origins who in 2017 replaced the former deputy speaker of the House of Commons, Sir Alan Haselhurst, who has since been given a peerage in the House of Lords. You will see that we are not racist, contrary to the picture painted by the Remain-supporting press. We're not English, we're everyone, because we have been forged by immigration (the Celts, Romans, Saxons, Vikings, Normans...). Democracy is debating in a market with an elected representative in person. And not to hand your far-off European destiny to some phantoms with whom you'll never be in contact and whom you see on the television in Brussels or Strasbourg, for a maximum of a dozens seconds voting 'yes' or 'no'. And doing so in accordance with orders received from on high without ever having cast an eye over the laws that are being adopted, in an authoritarian and automatic manner. It's like a plenum of the Chinese Communist Party – you call that democracy?”

For his coup de grace, this dyed in the wool conservative adds:“I've twice read the remarkable essay by [former Greek finance minister] Yanis Varoufakis, Adults in the Room, and there is no more convincing demonstration of the way Brussels' Europe operates. So I voted with my head and I was happy to see that the people had done the same. The United Kingdom had rediscovered the wisdom of the bee swarm, which is able to leave a hostile environment to establish itself in a more favourable place.”

'It's a consequence of the phenomenal inequality that has overtaken us'

Widdington can make your head spin. At every corner you can find a Demosthenes-like orator. It is as if everyone in the village was mulling over arguments that it would have been unhealthy to have spat out to a neighbouring compatriot, but which flow freely into the ear of a passing foreigner.

Mark, whom Mediapart met in the pub where he did not feel free to talk, was quick to unburden himself once behind the walls of his prosperous home about his vision for remaining in the EU: “I'm a liberal, a centrist if you prefer, but with a socialist strand that comes from our industrial revolution and the Victorian era. I now feel completely isolated, inaudible. As if I had lost my voice in this country where you can no longer tell the difference between Left and Right. Nothing is obvious here any more since Tony Blair, the Conservative who pretended to be Labour. Blair was simply the incarnation of the consequences of Thatcherism which shifted the United Kingdom and which has since been unable to find its centre of gravity since. Add to this confusion economic, social and malaise and the issue of identity then you have the main battalions of popular Brexit in place.”

Enlargement : Illustration 12

Mark laughs for a moment with that English humour that soothes the worst despair. “The Americans voted for Trump to get back to the blessed times of Rock and Roll some sixty years ago, they voted for Trump in the end to believe in 1959! The Brexiters went off the rails even more: they are dreaming of the Edwardian era at the start of the 20th century when the Empire was still going strong, when society was so structured that nothing unforeseen could occur, when London led the way in Europe and even the world, profiting from its position to make and unmake balances of power by playing on the rivalries between states. Too bad if working conditions were disastrous, too bad if people were dying because of lack of health care; they were the good old days, the Golden Age, just a vote away, ready to return as Boris Johnson and his fellows promised! Yet this time never existed then and it will never exist, even less so today in such a close-knit and interconnected world.”

Mark continues: “The English have regressed to being little children sucking their thumb in the illusory comfort of their cot. That's the light, traditional version. But there is a more oppressive and dangerous side: are we not suffering from a collective madness, close to that which the fascists revelled in during the 1920s and 1930s? That kind of madness is here but not only here: look at what's happening on the European continent, from Hungary to Italy. Worrying, isn't it?”

In his accent forged in Yorkshire, a county where people are known for their bluntness and calling a spade a spade, Mark concludes: “Here in Widdington, this ultra-privileged corner, a land of milk and honey, the political fantasy is that of a dominant class persuaded of its superiority, convinced it's gaining a head start for the Third World War. These superior English consider themselves the superior representatives of a superior people and of a superior nation which exists only in splendid isolation. These upper class English people, all these Old Etonians like Jacob Rees-Mogg, think that they don't want to take any orders from a continent infested with hereditary enemies, such as the Germans and, even worse...the French!”

To complete the tour of this village Mediapart met up with a rare creature in these parts – a Labour supporter. Janet is the head teacher at a secondary school in London and enjoys her job so much she continues to work there at the age of 65. It is a Saturday morning and she is with her cats on the verandah. She is happy in Widdington. And Brexit has not yet become the English equivalent of the Dreyfus Affair in France when citizens were prepared to come to blows, as shown in a drawing by Caran d'Ache at the time. “I'm surrounded by charming people,” she says. “Some of them let themselves get fooled by incessant propaganda passing itself off as news. Others, more intelligent, only listen in relation to their own interests and have no idea – and moreover want to have no idea – about the life of ordinary people, whom they look down on, going so far sometimes as to consider them to be parasites, with all the symbolic and social violence that that implies. At the same time alienation - in other words the process of no longer reflecting on things or having a critical perspective - is progressing at a terrifying rate among the working classes.”

Enlargement : Illustration 13

Janet continues: “As for our political classes, they've never had the courage to extol the benefits that Europe has brought us, and have been happy to treat Brussels like a punchbag that they bring out from time to time so that the people can get madly excited, as a form of release. The first fake news, well before Trump, concerned the constraints imposed by Brussels. From the dimensions of bananas to recipes for jam, everyone wanted to believe they were being oppressed by an omnipotent and nit-picking continental tyranny! This was in the face of the facts, which counted for nothing! It's a consequence of the phenomenal inequality that has overtaken us. Blair and even [Blair's successor as prime minister, Gordon] Brown (my weakness was to believe in the latter) did indeed bring in a minimum wage, but by letting unregulated financial markets make the law. In the face of this injustice which engulfs us, the people prefer to hark back to a little England, a haven of protection faced with a sprawling Europe. “

As she tells Mediapart about her thoughts about France's reaction to the Brexit negotiations, the headteacher does not mince her words. “When I see Mr Macron playing at being both Napoleon and [Charles] de Gaulle by wanting us to bluntly yield, I blow my top and say to myself: Let's pull out for good! Can you imagine the effect this has on the convinced and overheated Brexiters? It is totally irresponsible on the part of the French president to inflict on the British such painful reminders, just to pull the rug from under the feet of his domestic opponents. You don't add to the pain by playing on the traumatic memories of the European peoples! There's a risk in rekindling a British jingoism which we thought had died with the failure of operations in the Suez Crisis of 1956, but which reappeared like a sea snake during the Falklands war in 1982.”

But where in the end does she stand? After pausing for breath for some time, as if she were crossing the English Channel under water, Janet says: “I don't instinctively feel European. I have links, that are almost family links from a symbolic point of view, with the United States because of the Mayflower. I have links with Canada, Australia and New Zealand, as well as with the whole of the Commonwealth. I'm very attached to Ireland which I have never managed to consider, right up to recently, as a European country! It's Brexit which has, in some way, forced me to identify with Europe. By which I mean what it is supposed to be. Isn't that more important than that which was in the past? All the same, it will be some time before I find myself on the same wavelength as Austria....”

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter