Emmanuel is a 20-year-old student. One evening some police officers see him rolling a joint in public and intervene. It is the first time this has happened to him, and he has 10 grammes of cannabis in his pockets which, he explains, is for personal use. What penalty might he face? Under French law and practice there are many different outcomes. And since October 16th an extra possibility has been added to the arsenal already available under the law: the 'transaction pénale', a fixed penalty under which the offender pays an on-the-spot fine.

This new measure, however, will change nothing. There are already major inequalities in the way people caught smoking joints are treated, and which depend on their age, profession, where they live or their social class, according to a study of French penal policy towards drugs users over the past 30 years by the OFDT, the French Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, published on November 2nd (1).

Why, in the example given above, would Emmanuel be stopped by the police but Isabelle, a 54-year-old woman who smokes two or three joints at home while watching an American TV series, be left alone? The comparison may be fictional, but the figures that follow are not.

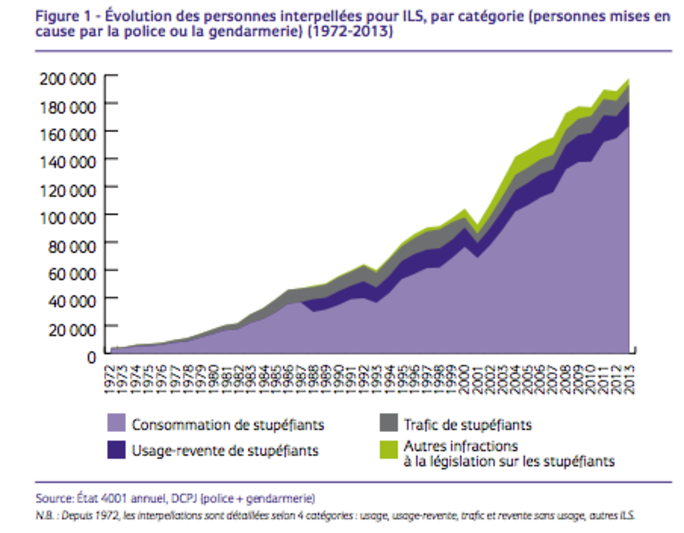

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Every year 165,000 people are stopped by the police in France for 'simple' drug use– of cannabis in over 90% of cases – which is 50 times greater than the number stopped 40 years ago. Since 1970, the number of people stopped for simple use has risen three times as fast as the number of user-dealers or drug traffickers. “When it comes to drugs, the activity of the security forces is centred on fighting demand,” Ivana Obradovic, the OFDT's deputy director, notes in the study.

The people who are arrested for drug offences represent just 4% of the 4.6 million cannabis users in France. Interestingly, the type of users arrested depends on the strategy being adopted by the police, according to a review by sociologist Marie-Danièle Barré dating from March 2008. She notes three main strategies: when the police seek to dismantle a drug-trafficking ring, in which case users are pulled in as potential informants or witnesses in catching dealers; when they seek to meet arrest targets, in which case bringing in cannabis users is an easy way to boost the numbers and justify funding; and the arrest of known individuals in known haunts, which is a way of keeping check on inhabitants of neighbourhoods seen as problem areas.

The authorities themselves contribute to a certain level of confusion over drugs figures, according to Patrick Peretti-Watel, François Beck and Stéphane Legleye in a book, Les usages sociaux des drogues ('The Social Uses of Drugs'). It cites a report from the Ministry of the Interior saying that men make up 94% of cannabis users, whereas health studies put male cannabis use at 66% of the total. However, 94% of those arrested for cannabis use are indeed men.

The 18-25 age group is also over-represented in the figures, making up 43% of those arrested but just 33% of users, according to health studies. Once a person is over 30, they tend to use cannabis in private places far removed from police surveillance, and it is generally easier to arrest users who are visible in public places than those who have the resources to use in their own homes.

An arrest for cannabis use can also result from being stopped for another reason, such as a complaint about noise or a simple identity check. So the unemployed, young people who have dropped out of school or are playing truant, or the homeless are, as a matter of course, targeted more.

Where someone lives is another major factor in whether they will be picked up by the police. The proportion of users arrested in the Paris suburbs is higher than the proportion of declared users in the population, but inside the Paris city limits the opposite is true. Perhaps this is because the Paris police force has other priorities, or perhaps, as the report suggests, “users in Paris have greater cultural and social resources to safeguard their consumption than those from the provinces”. Cannabis users in Paris are three times as likely to be senior managers or other professionals.

Taking just the situation in Paris, it appears that police activity does not reflect the true picture. An OFDT study in 2004 found that, in fact, young people living in the most favoured areas – the 6th, 7th, 14th, 15th and 16th arrondissements or districts – were more often consumers of alcohol, tobacco, psychotropic drugs, cocaine and even cannabis than those in the poorer areas in the north-east of the city.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

1. 'Trente ans de réponse pénale à l’usage de stupéfiants' ('Thirty years of penal response to the use of drugs') published November 2nd, 2015 by l’Observatoire français des drogues et des toxicomanies (OFDT).

The criminalisation of users increases - and so does cannabis use

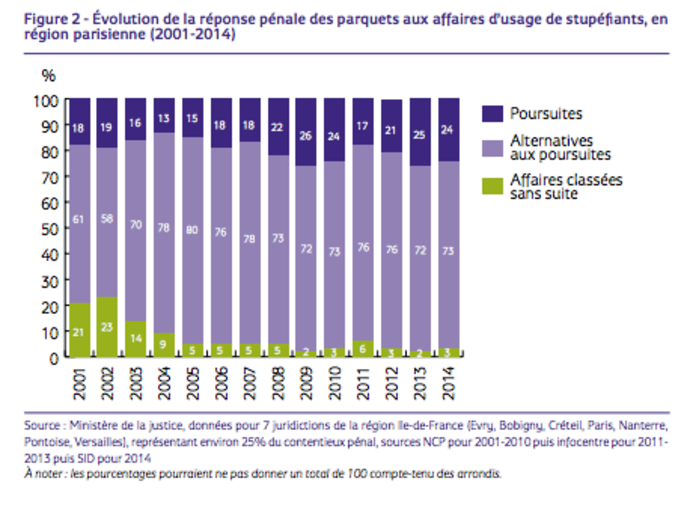

On top of this inequality of arrests, there are also disparities in the ways various laws are applied. The law governing cannabis use, passed in 1970, is still the mainstay of the penal apparatus. Anyone breaking it risks being fined up to 3,750 euros and sentenced to a year in prison. Emmanuel, our joint smoker facing the full force of the law for the first time, would not go to prison, but his case would be unlikely to be dropped completely either. Nowadays, no further action is taken in only 3% of cases compared with 21% of cases in 2002.

In fact, drug use in France has never been criminalised as much as it is today, and in 59% of cases that is just for simple using, a figure that has tripled over the past 10 years. At the same time, alternatives to prison sentences have proliferated since the 1990s, introducing swift sanctions meant to deal with low-level delinquents.

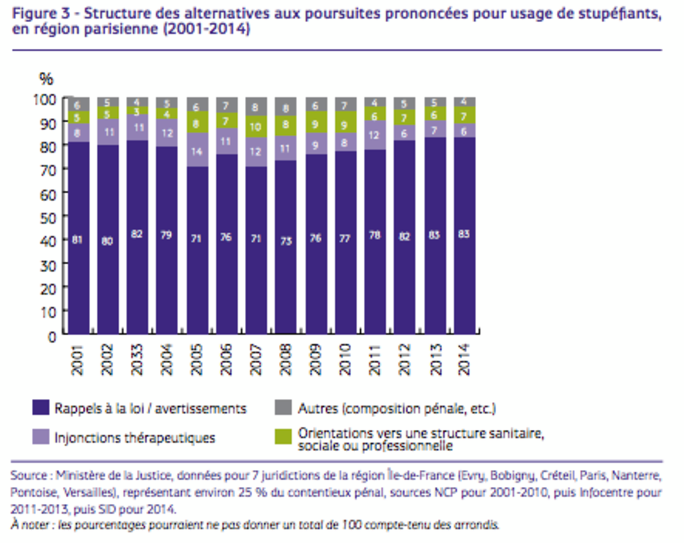

These are formal cautions and consist of a warning or admonishment in the form of a letter or a legal summons. They constitute 83% of the alternatives to prosecution. On the other hand, although the 1970 law was framed as meeting health concerns, the number of therapeutic injunctions and cases being closed with the offender being referred for counselling has fallen sharply, to 13% of the alternatives to prosecution from 25% in 2005.

Recommendations made by prosecutors for pre-trial agreements in which drugs offenders recognise what they have done, avoid a trial and conviction and are given a range of non-custodial punishments – agreements known as compositions pénales in French - have also increased in number. The number of fines imposed for drug use has doubled over the past decade, even if the average fine has fallen – to 316 euros in 2013 from 412 euros in 2002. Cases in which offenders are sent on reinsertion programmes, in particular courses aimed at increasing awareness, have also sharply increased in number, to about 3,000 in 2013.

The cost of such courses varies regionally, which generates another form of inequality, as a third of training centres charge 50-150 euros, another third charge 160-230 euros and the final third charge 240-300 euros. And the people sent on these courses tend to come from poorer backgrounds. Manual workers, for example, are over-represented, although they have the most limited financial resources. In another discrepancy, cautions are used in more than 75% of cases in Paris, while penalties are heavier in rural areas.

And there is yet more incoherence. Within a single jurisdiction, the approach can vary between individual prosecutors. Virginie Gautron, lecturer in criminal law and criminology at the University of Nantes, asked prosecutors in the same jurisdiction how they would respond to Emmanuel, the student arrested with 10 grammes of cannabis in his pocket. The first chose a simple caution, another added in a health referral – which means the case would be dropped on condition the person attended the appointment – a third went for a composition pénale, and the fourth for a composition pénale plus an awareness course. Gautron found the same variety of answers in the various jurisdictions she approached.

And as mentioned at the start, since October 16th the police can fine offenders on the spot, a penalty that also applies to other minor offences such as driving without a licence, unintentional violence or shoplifting, provided the merchandise in question is worth less than 300 euros. The idea is to have an immediate and concrete response without waiting for months of criminal proceedings. Customs officers can already fine offenders up to 1,250 euros, a measure intended to reduce case overload and backlogs.

In the case of cannabis, up to now a police officer who stopped someone smoking a joint had to contact the prosecutor's office, which would decide what to do. But prosecutors' offices were soon overwhelmed by the volume of calls, so local permanent directives were given, which were applied to a greater or lesser extent. One example was the instruction to issue a caution if the offender had no previous convictions and was in possession of less than 10 grammes of cannabis.

Even though the initial idea of the new law was to simplify matters by allowing the police to make decisions themselves without having to refer the case to the prosecutor's office, just as customs officers can, the power they were given seemed disproportionate. The police only have access to the national database of previous convictions, now called TAJ (traitement d’antécédents judiciaires). How can basing decisions solely on a database that is notoriously full of errors be justified?

The justice minister Christiane Taubira initially opposed having a fixed penalty, but a compromise was reached under which a requirement was added in the published decree stating that the prosecutor's office must authorise the procedure, and that it should be finalised with approval from a judge.

It seems only sensible that the police should not be able to decide criminal policy by themselves. But what is now the point of this new procedure? There is no longer a clear benefit in terms of saving time. The possibility of fining offenders has already existed for 10 years under the composition pénale, and lawyers, whose presence would not be obligatory, believe that the accused will no longer know their rights and will be less well defended. And police officers will still have to take offenders to the police station, even though they cannot suggest an on-the-spot fine once the person is formally in police custody.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

A lot of questions remain unanswered. Why would an offender agree to pay a fine immediately? What would need to be suggested for the person to agree? Will the poorest sections of society be more vulnerable to this use of on-the-spot payments to settle cases? Would there not be an even greater risk of major disparities between regions?

And despite the requirement for a prosecutor's authorisation and final approval from a judge, the principle is still troubling. Would not such authorisations most likely become automatic in practice, leading to a delegation of the power to judge to the police? And if the police investigate, arrest and mete out punishment, is that not a breach of the principle of the separation of powers?

One thing, however, is clear. France is not going down the road of decriminalising cannabis use, unlike much of the rest of the world which, like the United Nations, has decided that the repressive model is counter-productive, costly and inefficient.

France prefers to keep the 1970 law sacrosanct, while forgetting that this measure originally had a health element to it. The OFDT has noted a sharp rise in consumption of cannabis by 17-year-olds after a decade of stability. France now holds the record in Europe for cannabis use by teenagers.

---------------------------------------------------------------

The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Sue Landau

Editing by Michael Streeter