The International Monetary Fund recently published the conclusions of its annual assessment of the state of the French economy. These conclusions, carried out as part of a routine mission under article IV of the institute's statutes, are often quite formulaic and typically attract relatively little interest. However, the IMF's latest verdict on France, published on July 17th, certainly did catch the eye. For in effect the Washington-based organisation produced a two-page eulogy based on the policy programme – rather than any real measures that have been announced – of new president Emmanuel Macron.

According to the IMF report, the French government’s “ambitious reform program could go a long way in addressing France’s longstanding economic challenges”. The rest of the report is along the same lines, praising the “emphasis on reducing public spending”, the “broad and ambitious” labour reform strategy and the “planned corporate, capital, and labour tax reforms” which should “boost investment and job growth”. It is as if the IMF's dreams have all come true at once in the form of the economic policies proposed by Macron and his prime minister Édouard Philippe.

On the same day the IMF report was published France's two finance ministers, economy minister Bruno Le Maire and budget minister Gérald Darmanin, issued a statement “welcoming” the organisation's conclusions and making clear their pleasure at the “IMF's assessment” which “bolsters the government's strategy to increase our productivity: carry out structural reforms and reduce public spending while reducing taxation for the French people”. And indeed, in relation to anyone who simply reads the international institution's lavish praise without considering its own disastrous record when it comes to economic policies, this support could indeed help the French government's communications strategy. This is to present the new government as having a “realistic” and “rational” economic strategy in keeping with the doctrine laid out by Emmanuel Macron in his speech at Versailles on July 3rd: “facing up to reality”.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

However, the fact remains that for various reasons this positive picture barely stands up to analysis. First of all, judging from the timing of the IMF's conclusions they seem more political than economic in nature. From 2013 to 2015, similar IMF annual reviews of France have been published in May or June. That would have been difficult this year because of the presidential and Parliamentary elections held in May and June. But did the IMF need to publish its conclusions in July when its views were based on the new government's intentions rather than what it had actually done?

In 2012, the year of the previous presidential election, the IMF had taken more time to produce its report. Its conclusions were finalised at the end of October that year, having taken into account the new government's first decisions. As a result its conclusions then appear far more measured than those published this year, with an evaluation of the measures that had been taken and recommendations for the future. The 2017 evaluation has a very different feel and is essentially the IMF's opinion on a raft of policies whose impact in practice we do not yet know.

Moreover, the IMF's apparent haste to praise the new French government's policies may have come too soon to be able to evaluate a significant shift. Since the beginning of July government policy has taken a new turn which could put in doubt the balanced nature of its approach: priority has now been given to a reduction in public spending and taxes. Ministers have announced a cut of 20 billion euros – equivalent to 1% of GDP – for 2018, principally to finance the massive reductions in France's wealth tax or ISF.

This new policy is very different from the one initially promised, as the planned investment and support for consumer demand is now being put in doubt by the cuts. Yet the IMF ignore this altogether, while attaching particular importance to the plan to invest 50 billion euros during the five-year presidency, even though we don't know the precise nature of this investment or how it will be financed. The IMF would have been better advised to have shown more caution and to have waited for the new government's first measures to be inyroduced before coming to its conclusions, as it did in 2012. The IMF's decision to base its evaluation on a political programme rather than implemented policies is not in keeping with its role under article IV of its own statutes.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

But without doubt the most important issue is that the IMF's conclusions on France are, in reality, in complete disagreement with the organisation's own change in approach to economic policy. Since 2012 the IMF has been re-examining its priorities in the wake of the very serious mistakes it made during the EU financial crisis and in particular the Greek crisis. In January 2013 the IMF's chief economist at the time, Olivier Blanchard, and another IMF economist David Leigh published a paper in which they recognised errors in forecasting due to the organisation's underestimation of 'fiscal multipliers'; in other words, the impact that fiscal consolidation or reducing budget deficits have on growth.

This error was highlighted again in July 2016 when the IMF's independent evaluation body the Independent Evaluation Office (IEO) published a report on the institution's failings in relation to Greece. The IEO highlighted how the “IMF-supported programs in Greece and Portugal incorporated overly optimistic growth projections”. It also noted that the “more realistic projections would have made clear the impact of fiscal consolidation on growth and debt dynamics”.

This reflection led the IMF's own researchers to query much of what was called the 'Washington consensus' of the 1980s, namely support for liberalisation plus fiscal consolidation. In June 2016 three economists at the IMF, Jonathan Ostry, Prakash Loungani and Davide Furceri published an article with the title 'Neoliberalism: oversold?' which questioned the main principles of these old policies. Though the article did not represent the IMF's view as an organisation, it sought to highlight the limits of the approach used by the body over many years.

How the IMF forgot about its own studies

These various studies and articles seem to have been ignored by the IMF in its July report in which the issue of the fiscal multiplier in relation to France was not raised at all. In its conclusions the IMF defends the 'shock theory' by indicating that for the new government in Paris it will be “critical to exercise spending restraint from the start”. This would help place debt on a “downward trajectory” while giving the government “room for fiscal manoeuvre” in the event of a crisis.

What impact would this approach have on growth? None, according to the FMI which merely indicates that French growth “is on track to reach 1½ percent this year and further accelerate next year”. Indeed, the IMF seems to think the impact of spending restraint could even be favourable, as it had already factored in the fact that the 'fiscal consolidation' amounts to one percentage point of GDP for 2018. The organisation recognises that this consolidation represents “an exceptional effort by historical standards” and openly calls for a reduction in the number of public employees in “non-priority areas”, a reduction in spending by local authorities and on housing and health, and also urges pension reforms. All this, it suggests, will allow growth to accelerate. In doing so the IMF once again backs the idea of “expansionary austerity”, the concept whereby reducing state demand is supposed to boost overall demand.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

But what did the 2016 study published by IMF authors say about this issue? “...[T]he benefit of debt reduction, in terms of insurance against a future fiscal crisis, turns out to be remarkably small, even at very high levels of debt to GDP.” In other words, that study directly undermines the main argument of the French government and its supporters at the IMF. The article goes on to say “even if the insurance benefit is small, it may still be worth incurring if the cost is sufficiently low. It turns out, however, that the cost could be large—much larger than the benefit”. It continues: “The costs of the tax increases or expenditure cuts required to bring down the debt may be much larger than the reduced crisis risk engendered by the lower debt...” The approach taken by the French government and the IMF annual review is thus destroyed by the organisation's own researchers.

The 2016 article also specifically attacks the idea of 'expansionary austerity'. “Austerity policies ... hurt demand - and thus worsen employment and unemployment”. It then adds: “...in practice, episodes of fiscal consolidation have been followed, on average, by drops rather than by expansions in output.” The three economists cite evidence that on average a fiscal consolidation of 1 percent of GDP “increases the long-term unemployment rate by 0.6 percentage point”. They write: “In the case of fiscal consolidation, the short-run costs in terms of lower output and welfare and higher unemployment have been underplayed...”

All this is in line with the current research on the lasting negative effects of budgetary austerity. This has been highlighted in particular by Antonio Antonio Fatás and Lawrence Summers in a study which used the 2013 corrections outlined by Blancard and Leigh.

In other words, current economics research poses a real problem for the policies being carried out by the new French government. It is simply not possible to blindly assert the idea that a reduction in deficit will be beneficial to the French economy without taking into account these objections. Nor can one blithely accept the usual moral arguments about debt being “handed down to our children” and the beneficial and magical effect of what is known as 'Ricardian equivalence'. This is a theory claiming that when a government seeks to stimulate an economy by increasing government-funded debt through spending, demand does not increase.

It is quite surprising that the IMF fails to raise the question of the impact of fiscal consolidation and openly denies - without any explanation - any 'multiplier' effect on growth in France caused by austerity. The argument – not used by the IMF in this report - that the global economic outlook is now better than a few years ago does not hold water. It should be recalled that back in 2010, before Europe plunged into its spiral of austerity, world economic growth seemed stronger than it does today.

Moreover, two aspects of the French government's proposed policies cause real inequalities. Firstly the labour reforms, which seeks to impose moderation in salary levels and thus transfer workplace wealth towards capital. The IMF's favourable report is very clear on this issue as it says the labour reforms “should be complemented by continued wage moderation”. Yet every country which has employment flexibility has seen their inequalities get worse, as underlined by an October 2016 report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). It noted that for the first time, and thanks to the twin effects of austerity and reforms, inequalities are continuing to deepen despite a pick up in the world economy.

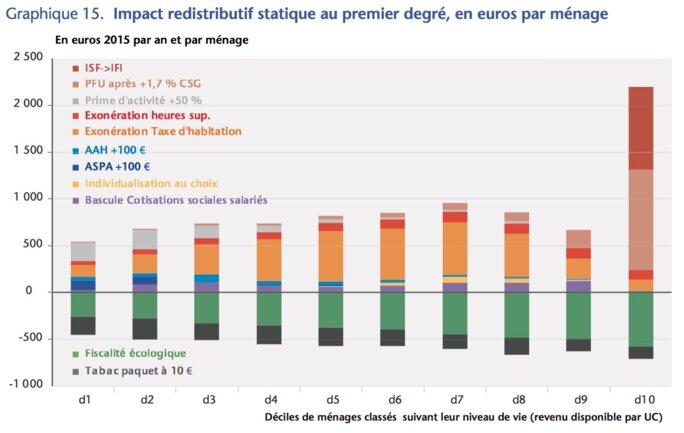

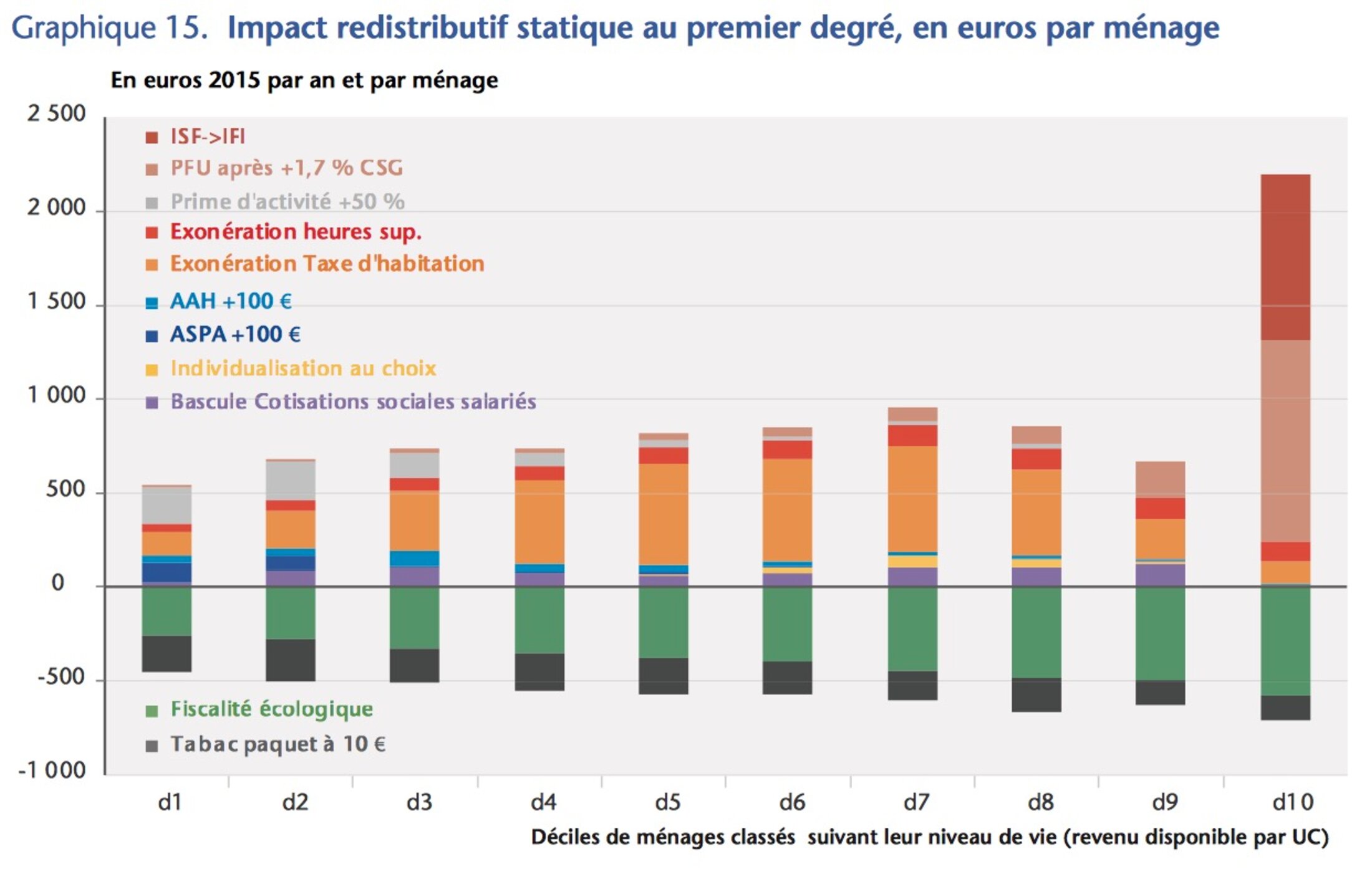

Enlargement : Illustration 4

The second aspect that increases inequality is the French government's fiscal policy. The French Economic Observatory (OFCE), a publicly-funded independent institution, has already shown in recent modelling the profoundly unequal nature of the tax measures that are being planned, and in particular the switch from a wealth tax (ISF) to a tax on property wealth (ISI), and of the implementation of a single standard deduction of 30% on revenues from capital, known as the prélèvement forfaitaire unique or PFU. Here again we see a transfer of wealth towards capital and the richest one percent. Such a policy can only be justified by the famous “trickle-down theory”, which holds that as the wealthy get richer this also helps those who are less well-off. In its conclusions on July 17th the IMF endorsed this approach by stating that the proposed reforms of corporation tax and tax on capital income “should boost investment and job growth”.

The problem is that there is no serious study that supports this theory. Instead, research tends to show that to get the maximum impact from lower taxes, you need to target poorer and indebted households. A combination of tax evasion, the appeal of financial markets and the freedom of capital to circulate could even lead to the conclusion that such tax gifts to the wealthiest can be very expensive: the benefits in terms of consumption and investment is limited and the budgetary cost is heavy and hits the most vulnerable the hardest.

Furthermore, an IMF discussion report from 2015 entitled 'Causes and Consequences of Income Inequality' consider the trickle-down theory to be null and void. “...[I]f the income share of the top 20 percent (the rich) increases, then GDP growth actually declines over the medium term, suggesting that the benefits do not trickle down...” write the IMF authors. This conclusion suggest the French government's current policies are dangerous. The IMF's optimism in relation to France therefore seems to have little credibility in view of the organisation's own work.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

The IMF's praise for the French government is even harder to understand given that the institution, like the World Bank and the OECD, is placing ever greater emphasis on the problem that growing inequalities pose for economies. “There is now strong evidence that inequality can significantly lower both the level and the durability of growth,” said the three IMF economists in their 2016 critique of neoliberalism. Other economists have come to similar conclusions. And studies cited by the IMF in their reports in 2015 and 2016 underline the importance of fiscal policy in the reduction of inequalities. This is exactly the opposite of the policies planned by France.

Moreover, it should be pointed out that France is not, as many claim, a “champion of equality”. The study by the OECD cited earlier shows that the level of inequality remains greater than that in the Benelux countries, northern Europe and Germany and Austria, even if the level of inequality has not suffered as much as elsewhere from the crisis, precisely because of the benefits system in France. So France does not need “more inequality” but even fewer inequalities – something the IMF completely denies in its conclusions.

The IMF's conclusions about France are, ultimately, extremely curious. They come across as premature and unequivocal, and reject most of the organisation's own research. It is as if in relation to France the old and increasingly discredited “Washington consensus' was still valid. The conclusions thus read more like political support for French leaders rather than a deep analysis of the situation.

Could the presence of the former French economy and finance minister, Christine Lagarde, at the head of the IMF explain this position? In any case the IMF's conclusions about France once again highlight the same problem raised by the IEO; namely, that of the IMF's independence in relation to national policies and in particular policies inside the Eurozone. The danger is that this could allow economic risks to re-emerge. It would seem that the Washington organisation finds some lessons difficult to learn.

------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter