Almost half a century ago the American historian Robert Paxton published a landmark book which went on to revolutionize the way France looked at Vichy France, the common name for the French State headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II, and in doing so sparked a major controversy. Vichy France, published in English in 1972 and in French a year later, established for the first time the scale of collaboration between Pétain's regime and Nazi Germany and its major responsibility in the deportation of Jews from France. Indeed his contribution to the issue has been described as the “Paxtonian Revolution”.

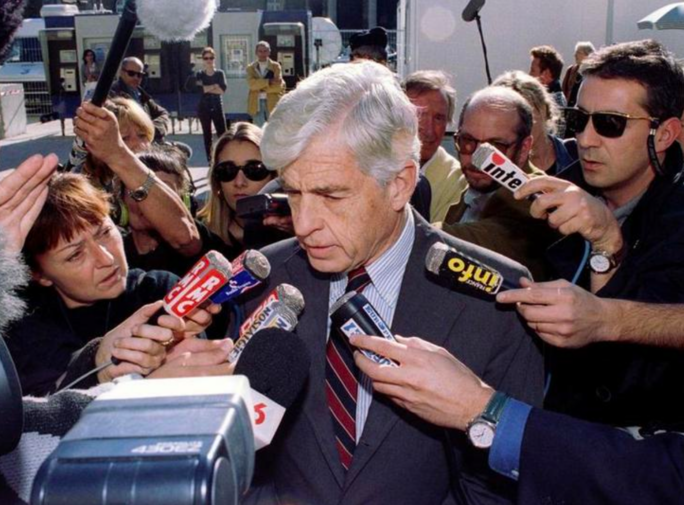

Since then Robert Paxton, now aged 87, and emeritus professor at New York's Columbia University, has continued to write about Vichy and fascism. As President Donald Trump prepares to celebrate the third anniversary of his election victory, and at a time when controversial far-right commentator French Éric Zemmour, who writes nostalgically about the Pétain era, pops up every evening on French television, Mediapart met the veteran academic at his New York home to discuss history and current affairs.

Mediapart: Professor Paxton, you are from the state of Virginia and your family was deeply affected by the American Civil War. Donald Trump recently described the impeachment process against him as a “lynching”, seeming to compare himself with the 4,700 people tortured to death in this way - of whom three-quarters were black - by white supremacists in the United States between 1962 and 1968. What is your take?

Robert Paxton: I thought it was profoundly offensive but then, practically everything he says is offensive. [The impeachment process] doesn't threaten his life, because lynching of course, was the most horrible of murders if people were murdered slowly, worst than crucifixion. But … he likes to portray himself as a victim of the false media, that is to say all the serious press and the rest of the world that is opposed to him.

Mediapart: Did he use this term to resonate with his base, who are sensitive to racial issues?

R.P.: Well, I think that he just wanted a strong word. I don't think he seriously calculated to evoke the south and and all of that because he has no sympathy for black people and the experience of black people, so I think he just wanted a strong word that would persuade his faithful followers that he's the victim of these terrible enemies.

Mediapart: But doesn't Donald Trump use lot of references - some dog whistle references - to racism?

R.P.: Well, he didn't start this. Richard Nixon was the president who reversed the position of the Republican Party... for a very long time the Republican Party in America was the party of Northern businessmen and of Southern blacks. American politics is …. not ideological. It's simply coalitions of other actors who think that they, their coalition, will assemble the most voters... and the Democratic Party was labour unions in the north and the planters of the South.

The Republicans were the industrialists of the north, of the black people, which was a little bit Abraham Lincoln's coalition. Lincoln was the man who freed the slaves and ... black people for a long time were grateful and they stayed with the Republican Party until they did nothing for them. Lyndon Johnson chose to break with the tradition of the Democratic Party and used the Democratic Party to improve the condition of blacks, and the Voting Rights Act of the 1960s offered some assistance and “forced open” Southern politics so that the blacks could vote.

Southern whites reacted very violently to this ... all the southern senators were democratic by long tradition. They left the party … some of them went all the way through to the Republican Party and Nixon saw that this was an opportunity. So he implanted the Republican Party in the south where it is now, the Republican Party is the party of Southern white people.

This is part of the deck that was dealt to Trump. And so he picked up on that and and he reinforced it. He added to that the northern white working class people who were jealous of the so-called advantages that Black people were offered, such as affirmative action, getting into universities.

So he managed to identify it and recruit northern white people who were bitter toward the advantages and ….this was the coalition that the Trump put together, [people] being angry at the black privilege, which of course is a nonsense, there's no such thing. But this is a part of his appeal ... and black people make a convenient scapegoat.

So it's an old playbook. And he does it with some genius because he's very good at manipulating crowds. He's very good at finding and identifying and bringing out the resentments of white people who aren't doing very well.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Mediapart: Before Trump was elected the question was posed: is Trump a fascist? Many of his attacks, insults and decisions regularly spark this debate. In 2004 you published 'The Anatomy of Fascism', an attempt to describe to describe fascist movements. Is Trump's administration fascist?

R.P.: Well, I wrote this book in order to, in part, make a reasonable case against overusing the term. Through the 1960s everybody called everybody else fascist. I wanted to use the term in a more precise and historically defined way.

I'm trying not to use the term fascist where it's not deserved. Now there are fascists in America, there always have been. There is the Ku Klux Klan, there's the American Fascist Party, and there was a party called the Silver Shirts in the 1930s. They're never very numerous, but they could be very violent and they were very racist. There is an indigenous American fascism, which is anti-black anti-Jewish, anti-Catholic, which goes back to something called the Know Nothing movement.

So there is an indigenous fascism, but I thought that the term fascism was not a very good fit with Trump. Though I'll admit that ... there's an overlap. There's some things about Trump that resemble Hitler. I saw the newsreel of his plane that lands and taxis up to the hangar and his audience is inside the hangar and I thought of Hitler in 1932. Hitler flew from place to place and he would arrive dramatically by plane, that's precisely what Trump was doing.

And his way of speaking, the self pity. Hitler was always playing on the self pity of the Germans ...after [World War I], who had been forced to pay reparations, he was very good at expressing his own self pity as someone who had suffered as a poor boy in Vienna and the self pity of the German people who have been treated badly after WWI, and that's the note [Trump] strikes also. And thirdly, he's extremely talented at finding scapegoats people to blame for our troubles. Jews, there were anti-Semitic dog whistles. And much more directly the blacks.

Mediapart: So you say that to describe him as a fascist is not totally false, but it's incomplete?

R.P.: There's a huge difference and … that is the economic policies. Because Hitler was surrounded by crackpot economists. Hitler … got some money from German businessmen, but … the conservatives wanted Franz von Papen [editor's note, who served as vice-chancellor under Hitler in 1933 and 1934] instead. They were scared of economic crackpots and [Hitler's] promises to shift wealth.

Hitler forced German businessmen to do things they did not want to do. Companies like chemical company IG Farben ... Hitler forced them to abandon [the] lucrative world market and concentrate on rearmament … he forced the business community to conform to government policy.

And it's the reverse with Trump. He's the party of big business. His American foreign policy and economic policy and environmental policy - and everything else - is what the businessmen want.

I'm looking for a term ... oligarchy. The rule of rich people is what he stands for. Oligarchy, whose policies are applied by authoritarian means. There's also populism. That is another aspect of it …..[the] identity of a person who proclaims that he is one with the people. And therefore, he can do anything he wants [faced with] constitutional constraints, because he is one with the people.

Mediapart: Will the American institutions resist? For instance, if Trump gets re-elected, could we see a more authoritarian regime installed?

R.P.: Well, the problem is that institutions can save us provided that the institutions are run by people who are committed to democratic values. But the institutions are falling into the hands of Trump's followers. As long as the Senate has a Republican majority and as long as the Republican senators believe fervently that Trump is their secret key to being re-elected [editor's note, a third of the Senate, which currently has a pro-Trump majority, is up for re-election in November 2020 at the same time as the presidential election] ... that institution is not going to help us... and the judiciary is being reshaped as we speak.

Senator [Mitch] McConnell [editor's note, the Republican Majority Leader in the Senate] is the real bad guy ... he's infinitely worse than Trump. Because he's effective, he's single minded and he has really, really revolutionized [the Senate]. He refused to approve something like 100 federal appeal court judges, [posts] which remained empty when Obama left office. It was a gross violation of constitutional duty.

As soon as Trump was elected, hundreds of federal judges were appointed. The judiciary has been radically slanted toward people whose social and political environmental values are deeply reactive. So that institution has been profoundly changed. It's been taken over, not just by Republicans but by the conservative wing of the Republican Party. So the institutions are not there to help us because they're in the hands of Trump's people.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Mediapart: It's a year from the presidential election and impeachment proceedings have been launched against Donald Trump. They are based on serious issues and the Republicans complain in private that they don't have much with which to defend him. What's your view about it?

R.P.: We're only a year away from an election, and that is the clean way to get rid of him Because we may fail, he may be re-elected - both are possible because the Democrats are making a mess of it.

I would love to see Trump impeached. [But] I think it is a dangerous weapon. It's like the old muzzle-loading guns, you're just as likely to have it blow up in your face as to kill an enemy with it. I think that it might well create a groundswell of sympathy for Trump. It will energize his followers.

It cannot go anywhere because the Senate will not hold the trial [stage] but it is the House that acts like a juge d'instruction [investigating judge] - our grand jury in the Anglo American system. They bring the charges and they bring it to the Senate and the senators have a trial [editor's note, if the first stage of impeachment goes ahead the Senate tries the case and need a two-thirds majority to convict and remove the president from office, which has never happened].

Mediapart: We hear a lot of talk in Europe about a return to the 1930s as if we were faced with an irresistible rise of reactionary, authoritarian and fascist threats. What do you think of this comparison that's being made by commentators, writers and historians?

R.P.: There are certainly some echoes of 1930s. But there are also some very profound differences. We're not in the throes of a Great Depression like in the '30s. So we're not in the midst of the depression, which changes everything.

The other vast differences are that you don't have the Soviet Union and the communist alternative which could be taken very seriously in the 1930s. And so it seems to me that we're not really returning to the 1930s. But fascism can revive in the sense that people are willing to give up on democratic institutions in order to to achieve some kind of prosperity or get revenge on people they don't like, without calling itself fascism. This kind of return to authoritarian politics, whether it's [Hungarian prime minister, Viktor] Orbán or [Polish leader Jaroslaw] Kaczynski or Trump, is something that would have been unthinkable for 30 years after the Second World War. So in that sense there is a return to a willingness to set aside democratic institutions.

Zemmour and 'selective memory' over Vichy

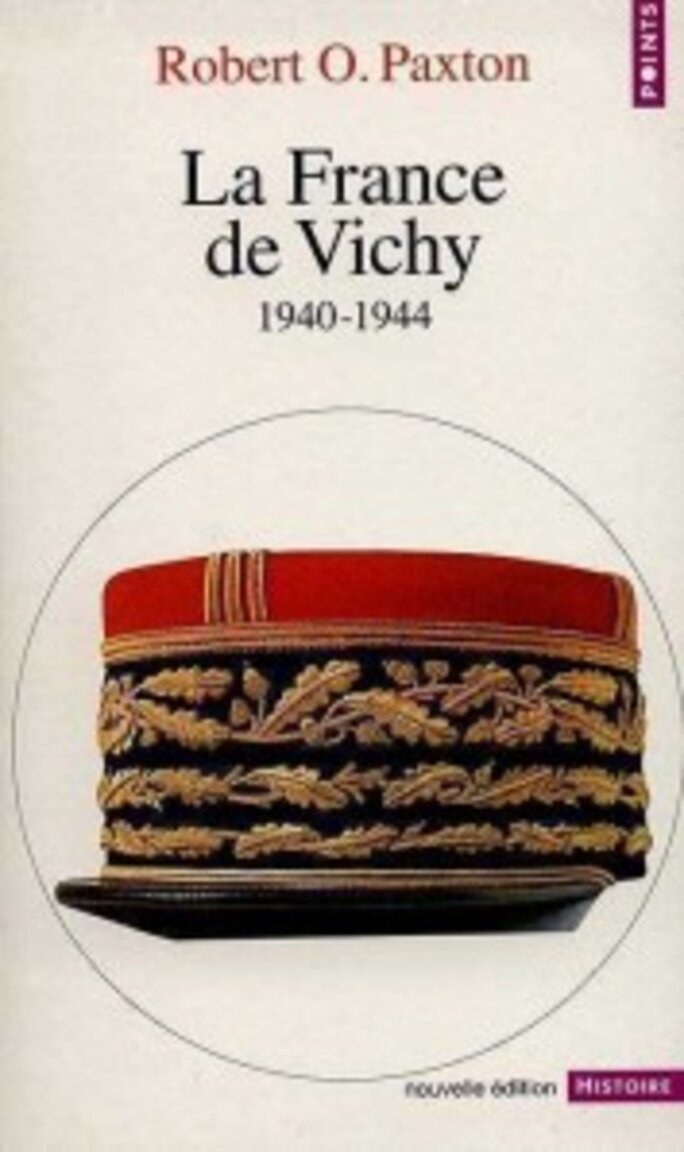

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Mediapart: Does the idea of a return to the 1930s also stop us from coming up with alternatives?

R.P.: I think it probably doesn't add much. I mean, it might help mobilize, to get your attention, but as far as giving you some ideas about what actions we might take...

Because when you think of the actions we should have taken and not taken back in the 30s, it was to attack Germany pre-emptively when they moved into Czechoslovakia 1938. And, you know, that's making war pre-emptively. And that's not a very attractive solution. So I don't think it gives us much guidance about what we ought to be doing.

Mediapart: How do you see the world in 20 years?

R.P.: Well, one of the things going to happen in 20 years is that Mar-a-Lago [Trumps' residence in Florida] will be underwater, and it will no longer be possible to deny climate change. But yeah, so I think that people will be paying attention to that issue in 20 years. Where they will be about race or gender or those kind of issues... I rather think that things go in a pendulum and I really think it's going to turn back. If not in the next election, then perhaps the one after.

Mediapart: What makes you say that?

I think people are very mobilized. I get 80 email messages a day, from Democratic candidates in every state in the country. They want money! (laughs). Whereas the Republicans have one or two huge donors who give them millions of dollars.

I think there's a real chance that the [currently Republican-held] Senate can be flipped. That Trump could be defeated in November, that's a long shot. But by the following election, simply by the return of the pendulum.

One worry is that the Republicans would have corrupted the political system ... they have all of these devices to limit people going to the polls, trying to keep the poor people and black people from voting. And if that's successful in enough places, then perhaps the system simply won't respond any more to the sort of pendulum effect that we have had in the past.

Mediapart: Hillary Clinton has suggested recently that she could stand again for the presidency as Joe Biden is currently running a bad campaign and she seems to think that Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders are too far to the left to take on Trump. What is your view?

R.P.: (laughs) Hillary fatigue is very strong. I think that's the worst thing ...if she comes back in then it just adds to the fragmentation. Nobody's going to vote for her except Bill ... I think that that would be the most destructive step imaginable. We've got these 23 candidates or whatever it is … and every one of them has some problem. The task is to construct a coalition of the traditional Democratic voters plus the undecided people in the centre. And the fear is that Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren, despite all their good qualities, will turn off those middle voters. And if somebody else runs as a third candidate as an independent, if we nominate somebody quite progressive, and somebody more centrist runs as independent, that's really bad. One can't be wildly optimistic because there's so many obstacles.

Mediapart: I would like to talk about France which you know well and continue to visit regularly. In 2014 you were at odds with a far right polemicist, Éric Zemmour. He had just published a book called 'Le Suicide Française' ('The French Suicide') in which he sought to rehabilitate the Vichy regime. He even criticized the “Paxtonian orthodoxy” which he suggested had worsened Vichy's image. Zemmour is part of that group of people who see Vichy France as a “shield” against Nazism. He also insists that Pétain saved many Jews. You took apart these theories in your book Vichy France, which was published in 1972 – 1973 in French - and caused a scandal at the time. In 2014 you wrote that Zemmour was in reality an apologist for a regime which indulged in “active and pathetic collaboration”. Recently Zemmour, who has become the main television personality for the vengeful, Islamophobic and homophobic Right, once against stated that Pétain had saved French Jews, and he targeted you again. Will this debate about Vichy France never end?

R.P.: First of all, simply on a level of polemical skill Zemmour is an extraordinarily clever debater. And I think ... it is certainly the case in France ... that people quarrelling with each other is a spectator sport. People love to watch, argue with each other and they don't have to agree with what they say but they admire the skill of someone who is really good at demolishing his enemy and I think that Zemmour is irresistible.

Mediapart: So in that he's like Trump?

R.P.: Like Trump. So that's a part of it. And secondly, I think that in France like the United States ... people aren't necessarily rising economically. They're stuck with dead-end jobs and salaries that don't increase. In the United States, we have something new; in the old days, everyone was quite sure that they were going to be a little bit better off than their parents, and that they would own a home and a car. And it's no longer true that you will own a home. The price of real estate has become very high and lots of people never manage to own their home – even though that was traditionally the definition of the middle class. And I think in France, too, there must be a sense that things are frozen and that.... lots of people feel that traditional politics and the existing parties and leaders are not going to solve their problems.

The existing political establishment is exhausted and has run its course. I mean, it's hard to say parties because they keep changing. But the the traditional political leadership doesn't seem to have much to offer. And I think it's very dangerous that there's this vacuum.

Mediapart: And so we come back to Vichy. How can you explain that fifty years after your book was published and after years of debate, there is still so much of this nostalgia in France for Vichy?

R.P.: I think Pétain personally was always very popular, and it was possible to separate Pétain from the regime. The regime was hopeless because the Germans were making them do everything. The Germans really didn't have many people in France - they needed all their soldiers on the Eastern Front, and they had quite a small occupation force. So it was not a matter of force but they did have the capacity of forcing Vichy to do things. So I don't think the regime appeals very much but Pétain, personally, was someone who was always above suspicion because he looked wonderful and he represented heroism and the tradition of victory of WWI and he was doing the best he could, at some considerable sacrifice. He's partly a figure of self-sacrifice, even that explains his failure to achieve things. It's not his fault, etc.. So that formula continues to work rather well.

And people must have forgotten the details about collaboration. They forgot the details of the young Frenchmen who had to go and work in German factories. You've lost all the details. Like the deportation of Jews - maybe some people think that's a good thing? And certainly lost details like the STO [editor's note, forced labour], rationing and hunger, and that it was an awful time. I think a lot of those details about how awful it was have been forgotten; you had this nice image of Pétain doing the best he could to say no to the trend.

Medipart: Are you surprised that France is still discussing this?

R.P.: I am because I thought that it would be over. But I did remind myself, and some people, that in the United States, the Civil War continued to provide the structure of American politics for 100 years.

What brings [memories of Vichy France] back in France? I don't know, immigration, the perception that France is declining and they were looking for some some saviour to bring back the sense of being a great power, of being a country that matters, that has the intellectual leadership of the world and is a serious military, economic and cultural power.

Mediapart: France is embroiled in yet another row about the veil worn by Muslim women, a controversy started this time by President Emmanuel Macron's education minister Jean-Michel Blanquer. Why does this government do that?

R.P.: Well, I guess that's politics. He's trying not to leave any space on the Right. He's got to let the space on the Left take care of itself. So that I think must be his calculation, that he must not allow a haemorrhage [of support] to take place on the right.

Mediapart: Despite the unprecedented repression, the unprecedented police violence, Emmanuel Macron remains popular in the United States. Why? Because he's the most liberal of the leaders on the world stage?

R.P.: Orbán, Boris Johnson, Kaczynski ....in that company he looks moderate and cozy.

Yeah, they look at his TV image and say, yeah, he must be okay. And he sounds reasonable. His image is pretty good here. He cooperated with the United States on foreign policy in Syria, in various places we were working together. Americans don't know anything about ... what's going on in France.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- This interview was carried out in English. The French version can be found here.