It is never a good idea to hang around in the forests of Austria. Ask celebrated football manager José Mourinho; it was while he was there preparing his Chelsea stars for the new season that a letter from the Spanish tax landed on the desk of his lawyers on July 23rd, 2014. The letter from the Madrid tax office, the Agencia Tributaria de Madrid, did not contain good news; it announced an investigation into the manager's taxes when he trained top Spanish club Real Madrid between 2010 and 2013.

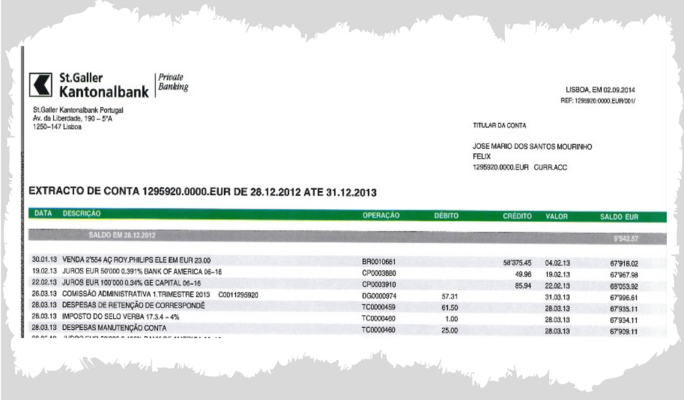

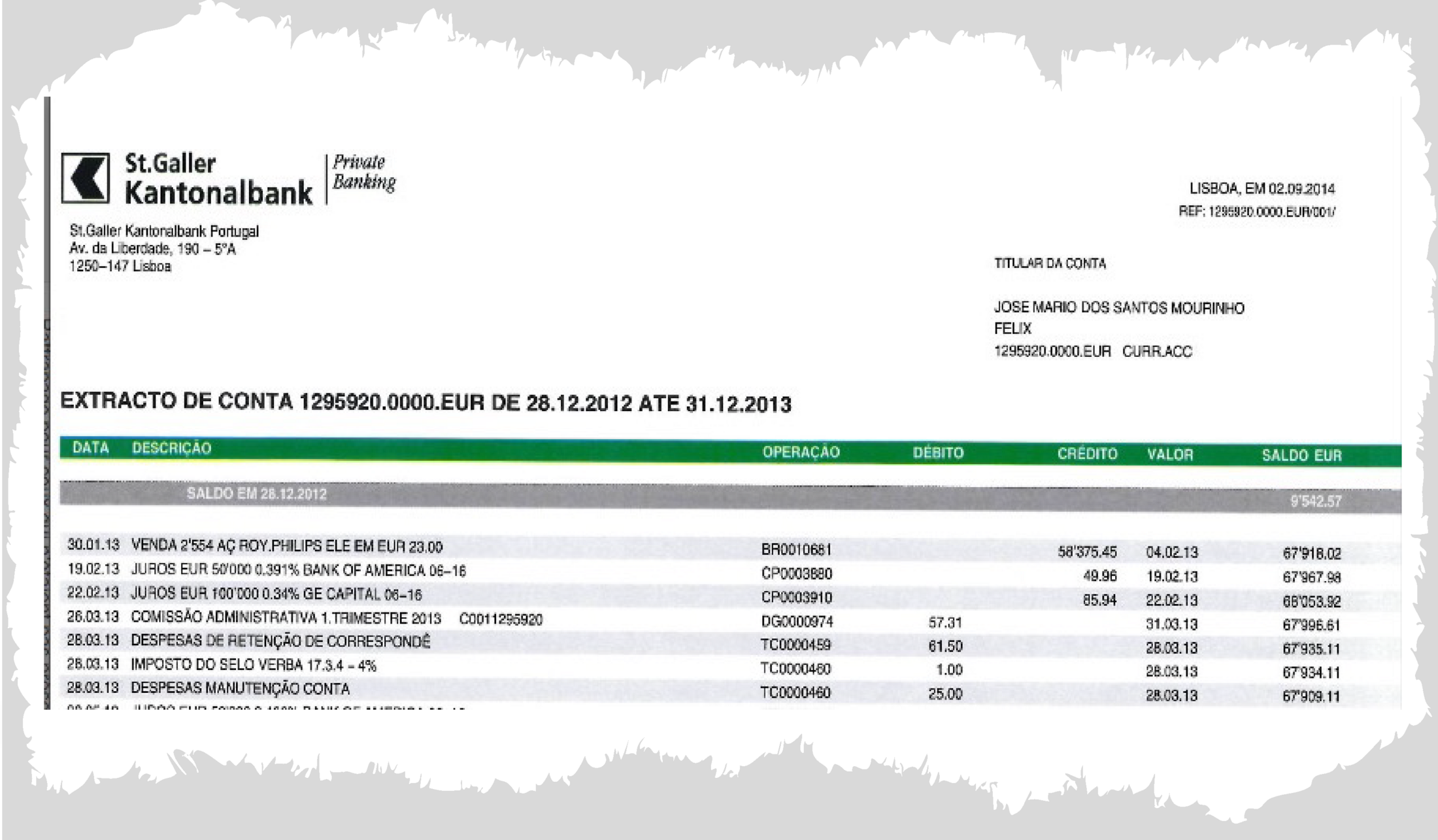

The ever-alert Portuguese manager, known as the “Special One”, knew how far this could lead, from the British Virgin Islands to New Zealand and ultimately to the undisturbed hiding place of his secret jackpot: an account in Switzerland with the St.Galler Kantonalbank (SGKB) bank. This was where he had 12 million euros that he had forgotten to declare to the tax authorities.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

But the Spanish tax authorities had found the money and imposed a tax adjustment on Mourinho of 4.4 million euros, including penalties. This came as a relief to his lawyers who feared that their client would find himself before the courts and even be given a prison sentence. Since then Mourinho has moved to Manchester United.

For exactly ten years the offshore system had showed impressive efficiency. It had been put in place in 2004 by the manager's agent Jorge Mendes who later extended it to his wealthiest clients such as Cristiano Ronaldo. The money reached the peaceful destination of the Swiss canton of St. Gallen via Mendes's companies in Ireland, then arrived in accounts held by offshore companies registered in the British Virgin Islands. This is according to documents from the Football Leaks whistle-blowing platform, accessed by German weekly magazine Der Spiegel and jointly analysed by the European Investigative Collaborations (EIC), a consortium of European investigative media that includes Mediapart.

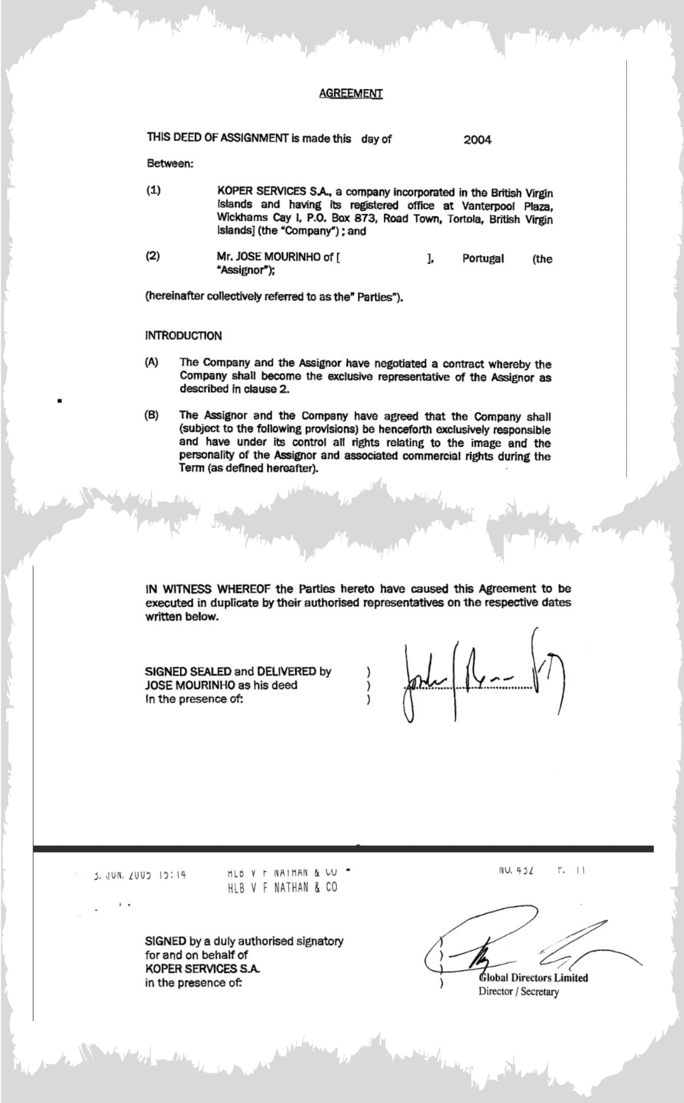

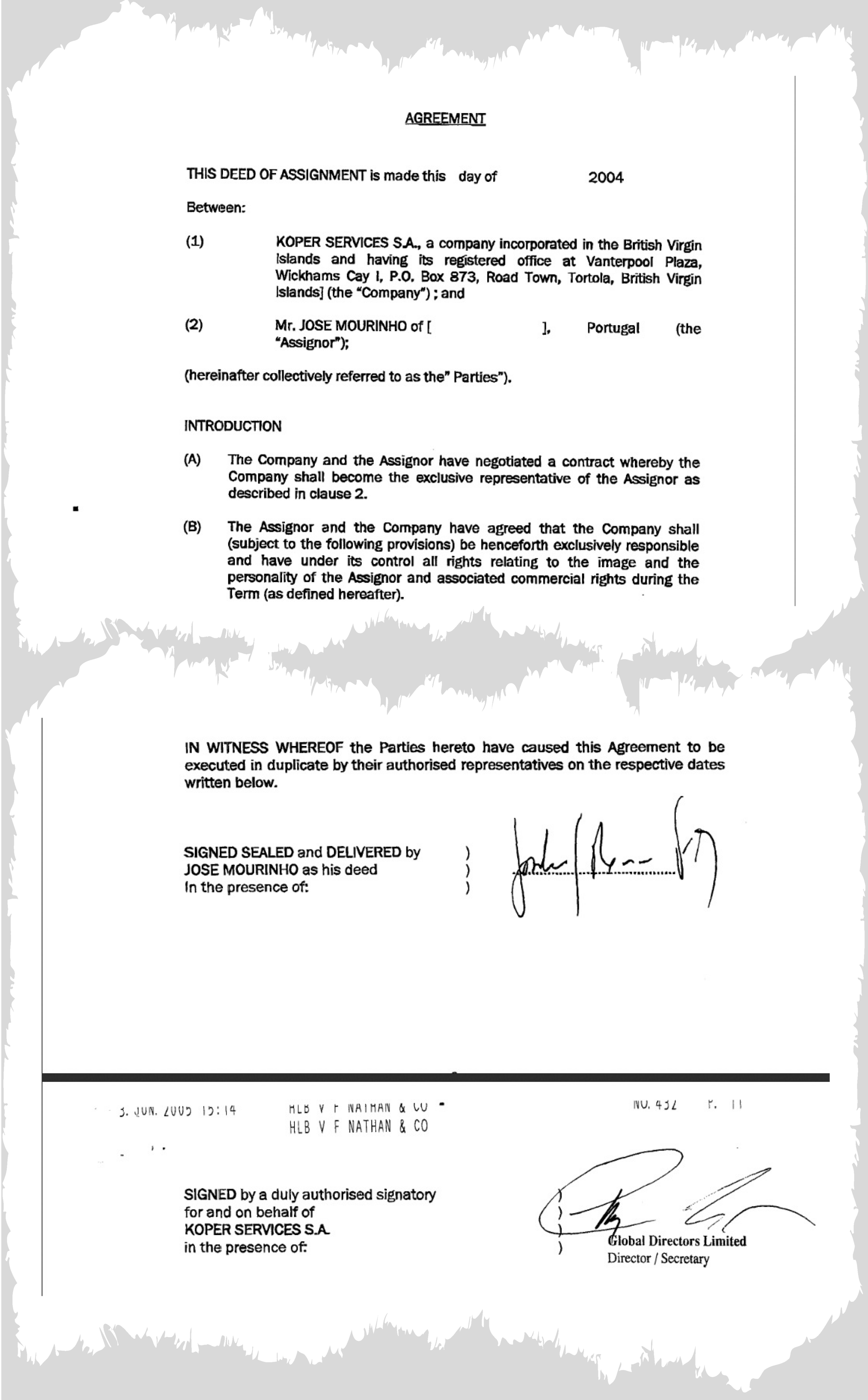

The Football Leaks documents also show that Mourinho went even further than his illustrious colleagues in the Mendes system in terms of sophistication in hiding the money. In the fine tradition of Russian dolls, the manager's shell company in the British Virgin Islands, called Koper Services, was held by a trust in New Zealand and administered by figureheads, which hid the name of the manager and his family. Above all, the EIC investigation shows that Mourinho's accountants and lawyers face suspicions of having misled the tax authorities by making them believe that the company – which was an empty shell – had a real business activity and had to pay significant expenses, minimising its taxes.

This tactic achieved its goal both in the Spanish tax probe and the investigation carried out in 2010 by the British tax authorities into his income during his first period at Chelsea from 2004 to 2007. On each occasion Mourinho reached negotiated settlements, paying for his undeclared income but avoiding criminal proceedings. It also allowed him to remain discreet about his infringements.

Thanks to Football Leaks the tax authorities in both countries are perhaps going to have to re-examine the cases. Having studied the documents in the possession of the EIC, Albert Sánchez-Graells, a specialist in Spanish law at Bristol University, who trained at the Madrid bar, said: “It is clear that a criminal tax fraud investigation needs to be launched into José Mourinho's tax affairs,” he said. “The evidence suggests that the tax authorities were misled when conducting investigations into Mourinho's offshore scheme, which was constructed to dodge millions of pounds in tax.”

Questioned by the EIC, the law firm Senn Ferrero, who represent the manager, could do nothing other than confirm Mourinho's tax adjustment and the sums discovered by the EIC. In contrast they were very reticent in their response on other issues: the offshore setup, the hiding of money and the lies. Via a statement from his agent, Mourinho has denied any wrongdoing and insists that he was “fully compliant” with his tax obligations to “the Spanish and British tax authorities”.

José Mourinho, aged 53, was the son of a footballer though not especially talented at the game himself. He started discreetly in the sport as a translator at a club before climbing the echelons, learning from great managers such as Englishman Bobby Robson at Sporting Lisbon and Louis Van Gaal at Barcelona. At the time he was a self-effacing man, though his tactical analyses were appreciated. That was why Robson took him to Barcelona in 1996. Then 'Mou', as he is sometimes nicknamed, was made head coach at FC Porto in 2002 and became one of the most effective coaches in the world, a master in the art of strategy – often defensive – and motivating his players. A big mouth at times, he is never better that when an “us against the rest of the world” approach is required with an inferior team, where a burning fury to prove the opposite can destroy opponents.

The man who loves to be hated has been a champion in every country where he has managed a club. In Portugal this was with FC Porto in 2002 and 2004, with Chelsea in England in 2005 and 2006, in Italy with Inter Milan in 2009 and 2010 and in Spain with Real Madrid in 2012. He has won the Champions League twice, once with Porto in 2004 – an incredible victory by a smaller club against some of the giants of the game – then with Inter Milan in 2010, beating Barcelona on the way to the title.

Comments from the impeccably-attired 'bad boy' Mourinho are always eagerly awaited and are usually nasty remarks aimed at opponents, for the manager practices attack psychology. He has a very high opinion of himself and loves letting people know that.

Mourinho's lawyers at loggerheads

As a result of his successes, Mourinho has been able to accumulate millions. He was at one time the best-paid football coach in the world but his favourite enemy, Pep Guardiola, has now overtaken him at Manchester City. At Chelsea in 2004/05 he earned 6 million euros a year, then got a 1.2 million euro rise for taking the London club to its first league title in half a century in his first season. When he moved to Inter Milan in 2009 he made 17.63 million euros a year, double what was announced at the time. Later at Real Madrid he earned 14.9 million euros. So even before his move to Manchester United in 2016 –where he will receive 46.5 million euros over three years – he had amassed 140 million euros in salary payments.

Though Mourinho underwent a small drop in salary in his move from Inter Milan to Real Madrid, this was made up for the fact that the Spanish club granted him a 2.3 million-euro bonus for image rights. These are largely artificial payments, designed to pay out bonuses that attract less tax, and paid into a company created for this purpose. It was precisely this image rights jackpot, paid by his clubs and sponsors, that Mourinho has never declared to the tax authorities.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The Portuguese manager's offshore financial journey began in 2004 when Chelsea started to pay him his first large image rights bonus, which was 1.5 million pounds over three years. It was then that he created his shell company, Koper Services, in the British Virgin Islands. The money was initially moved via his agent Jorge Mendes's companies MIM and Polaris, registered in Ireland so the clubs and sponsors were not too alarmed.

Mourinho was punished for the first time by the British tax authorities, who delved into his 2004 to 2008 income. In the agreement that the manager later signed with the authorities in 2010 to close the matter, he recognised his “failure to meet all my obligations” under tax legislation.

But the British tax authorities HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) showed leniency. Though the manager should normally have been taxed at 40%, the undeclared money was only taxed at 19% which came to 288,300 pounds – a saving of 300,000 pounds. He also paid no fine for not having made a declaration of these funds, even though he had said nothing for four years.

This reduced bill was possible through Mourinho and his team claiming that Koper Services had sizeable tax-deductible costs, even though in reality it was an empty shell company simply designed to lodge the money. This is shown clearly in the Football Leaks documents to which British tax inspectors have not – yet - had access. But the Spanish investigation would later prove that the million euros in costs claimed for Koper Services was to a great extent artificially inflated.

After signing this very good agreement with the British tax authorities at the beginning of 2010, José Mourinho continued to have access to his Koper Swiss bank account as if nothing had happened. At the time he was in charge at Inter Milan with whom he won the Champions League. Then he moved to Real Madrid where he received 2.3 million euros as an image rights bonus. After winning the title with Real Madrid in 2012, a title they had been hankering after for four years, the Portuguese manager got a modest rise; 18 million euros a year in salary plus an image bonus of 3.17 million euros.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Mourinho did not pay income tax on his image rights income as he did not declare it. For seven years the money thus piled up in the Koper account in the British Virgin Islands. By the time the letter from the Spanish tax authorities arrived in July 2014 the total amount had reached 12 million euros. The Spanish investigation was potentially devastating for all of Jorge Mendes's clients, who also risked being discovered.

The football agent then hired a friend to come to the rescue of his stable of clients; the lawyer Julio Senn, the former director general of Real Madrid and founder of the Madrid law firm Senn Ferrero. Senn spoke with the Swiss bankers who looked after Mourinho's account: the whole business unnerved them. The lawyer feared that the Irish companies used in the Mendes system might be considered by the tax inspectors to be an unlawful means provided to the footballers to avoid paying taxes.

Julio Senn discovered the scale of the setup from Andy Quinn, Jorge Mendes's accountant and offshore provider in Dublin, who had set up the Irish companies. Senn's relations with Mendes's long-standing lawyer Carlos Osório de Castro quickly became difficult; it was Osório de Castro and Quinn who had set up the system, even if the former denied it, telling the EIC that he did not practice in relation to tax issues.

The Spanish tax inspectors asked themselves a very simple question: had José Mourinho paid taxes on the income from his image rights in any country at all between 2010 and 2013? According to the EIC's information, Julio Senn was persuaded that he had not, but he needed confirmation from his fellow lawyer Carlos Osório de Castro, the man who knew everything, even though the latter today denies playing any role in tax issues.

A double defensive line

Senn was also helped in his work by a tax expert, lawyer Diego Rodriguez, from the law firm Garrigues. Rodriguez discovered a catastrophic situation, which moved him to ask that his advance fee of 20,000 euros be swiftly paid by Mendes and Mourinho before the situation got worse – which he saw as inevitable. For his part, Senn feared that the situation would get worse when Mourinho discovered the seriousness of his tax affairs.

According to the EIC investigation, Rodriguez expressed strong reservations about the setting up of the offshore scheme. He complained that he was ignored by his fellow experts, but was still hopeful that criminal proceedings could be avoided. Given that Mourinho was willing to pay the tax authorities, the Spanish tax lawyer hoped this would stop the tax inspectors from sending the file to the prosecution authorities. That would be a first victory.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

But Rodriguez knew that payment would be required and he did all he could to limit the amount of the fine he felt was certainly coming. Mourinho's lawyers now took opposing stances. Those in Senn's law firm thought they had everything to lose in getting involved in a battle with the tax authorities as Osorio was advocating, because they considered the fight was lost before it started and would have considerable consequences in terms of media coverage.

The Madrid lawyers hoped to make reference to the British settlement but the Irish accountant Andy Quinn, who was at the heart of the tax setup, advised against this. He explained that the British tax authorities had already considered image rights as disguised salary and had taxed them. They should not give the same idea to the Spanish authorities, he warned. Above all, argued Quinn, referring to the British tax investigation would show tax officials in Madrid that Mourinho had already been punished for the same scheme, and that he had continued with it in full knowledge of this.

The concern went up a notch when the Madrid lawyers grasped the virtual nature of Koper Services as a company. In theory the Portuguese manager had handed his image rights to the company, which then exploited them independently. But in that case, how was Mourinho paid? Nothing was set out in the contract signed between Koper and Mourinho in 2004. Yet if the company was really a independent entity, the manager would have not given his rights away for nothing.

Another problem lay in claiming that Koper had a real business activity. Julio Senn asked the accountant Andy Quinn if there were really employees at the company domiciled in the British Virgin Islands, or equipment to develop any activity. To the lawyer's dismay, the Irish accountant confirmed that it was simply a shell company.

But it was not game over as far as the lawyers were concerned and they found a way to fight back. They claimed that Koper really did engage in business activity and that they charged it to the manager in the form of commissions. Through skilful accountancy rewriting these commissions became costs that gave rise to a reduction in tax owed, as the British tax authorities had admitted. The problem was that it was an artificial construct aimed at deceiving the Spanish tax authorities.

In October 2014 Senn did the sums of the money lodged at Koper; on December 31st, 2013 the statement of account indicated that the company owed 11,979,657 euros to Mourinho. According to the Football Leaks documents, the draft accounts drawn up by Quinn at the start of the Spanish tax investigation make no mention of any costs. Undeterred the lawyers came up with the tax equivalent of a skilful dribbling manoeuvre. In the document they ultimately gave to the Spanish tax authorities a column appears called “Koper commission”. All of the payments to Koper were thus hit by costs of 13.99% or 1.49 million euros.

However, there was still a major problem: the company's bank accounts did not mention these commissions. And how could a company with no activity have so many costs? Fortunately for Mourinho these questions did not occur to the Spanish tax authorities who were deceived in a two-step move.

First, lawyer Julio Senn took the risk of referring to the British tax investigation. Secondly, in support of his approach the Madrid lawyer produced a very curious contract signed on June 23rd, 2015, between Koper and Mourinho. This extraordinary document claims to confirm after the event an oral agreement from 2010 that allowed Koper to charge costs to Mourinho. It was tax lawyer Rodriguez who had the idea of inserting the word “oral” and to claim that the agreement dated from December 1st 2010. That was the very first day of the period targeted by the Spanish tax investigation.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

The question then arises, however, over to whom Koper really belonged. If its owner is Mourinho, why was he paying charges to himself? Here again the Spanish tax authorities were completely taken in. Koper's shareholders in the British Virgin Islands are local trust companies who serve as dummy shareholders. The real owner is an “irrevocable trust” called the Kaitaia Trust registered in New Zealand, which is also run by a supplier of offshore services.

Armed with this double defensive line of figureheads, the lawyers had no hesitation in supplying a document attesting that Mourinho “is not a direct or indirect shareholder” in Koper. They hoped that the authorities would accept this.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

They did so. In July 2015 the Spanish tax authorities accepted the 13.99% costs accrued by Koper, which meant a million euros could be deducted from income. Mourinho owed a penalty of 1.146 million euros on his image rights, plus 3.3 million euros in late tax payments.

In Senn Ferrero's response to EIC, however, the law firm committed an enormous blunder. They accepted that “Mourinho opened the company Koper” on his arrival in Britain. In other words, the admitted information that they had gone to great lengths to hide from the tax authorities.

Did they do so because they knew that the EIC had the documents to prove it? Or because in their eyes they had already done the crucial thing, which was to avoid criminal proceedings? The lawyers had feared a similar outcome to that of Barcelona's Argentinian star Lionel Messi, who on July 6th, 2016, was given a 21-month prison sentence by the Spanish courts for having defrauded the tax authorities of 4.1 million euros in a similar system set up by his father Jorge.

On the tax front, therefore, Mourinho has beaten the Argentine footballer hands down. His lawyers have succeeded in hiding the essential: the document setting up the Kaitata Trust in June 2008, signed by Mourinho who founded it and controls it. The beneficiaries are his “current wife and his children”. José Mourinho has thus claimed that his wife and children have demanded 1.5 million euros in charges from him for a company that provides no service.

It may not have been the most inspired story in the world but it was enough to impress both the Spanish and British tax authorities; unless now the Football Leaks documents reawaken their curiosity.

Lawyers acting for José Mourinho and Jorge Mendes said on Saturday, December 3rd: “Jorge Mendes is not a tax advisor and never recommended any image rights structures to the players.” In a statement the lawyers also said it was the players' clubs who had recommended the setting up of specific structures. “All structures were created at the request of the clubs on the advice of tax professionals from the relevant jurisdictions,” they said.

Questioned by the EIC, lawyer Carlos Osório de Castro denied being behind the creation of the offshore system involving Mourinho. “I have nothing to do with the creation of image rights structures for the people mentioned,” he said. “I categorically deny the accusations made against me.” Echoing his Spanish colleagues at Senn Ferrero, representatives of Mendes’s company Gestifute, and Ronaldo’s lawyers, Osorio said he “regretted” that the EIC based its information on what he said described as “stolen documents” that were “manipulated”.

Approached by the EIC, Mendes’s Ireland-based accountant Andy Quinn did not respond.

In Britain Chelsea FC said they had always respected the law in relation to the payment of image rights, including in the case of José Mourinho.

HMRC in Britain said they could not comment on individual cases. But the tax authorities noted that they did scrutinise arrangements between clubs and their employees on questions of image rights, to ensure that taxes are paid.

Meanwhile football agency GestiFute, founded by Jorge Mendes and which represents Mourinho and Cristiano Ronaldo, who is also facing tax-related allegations, issued a media statement after the first revelations concerning Ronaldo were published on Friday, December 2nd. It said: “Both Cristiano Ronaldo and José Mourinho are fully compliant with their tax obligations with the Spanish and British tax authorities.

“Any insinuation or accusation made to Cristiano Ronaldo or José Mourinho over the commission of a tax offence will be reported to the legal authorities and prosecuted.”

GestiFute added that neither Ronaldo nor Mourinho “have been implicated in legal proceedings of the tax evasion commission in Spain”. It noted it had taken legal redress against claims of tax evasion and stressed it had always acted with "the highest degree of professionalism in relations with [its] clients and authorities”. The company accused the EIC media consortium of operating in an “insidious” way concerning the stars' tax obligations.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- Mediapart's report in French, on which this article is based, can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter