Amid the spectre of the euro collapsing as the debt crisis deepens, the words of General Charles de Gaulle, one of the original protagonists of pan-European cooperation, have a prophetic ring."Do we, or do we not, want the Common Market to be supplemented by a political organisation without which economic construction will ultimately decline?" he asked in 1962. Antoine Perraud argues that it is time to rediscover de Gaulle's vision of a Europe united by political action and not finance, a vision that was paradoxically later championed not by the General's so-called political heirs in France, but by German Green Joschka Fischer.

-------------------------

Those on the French right who claim to be the political heirs of Charles de Gaulle are often the very people who dig the grave of his ideals. They have failed to understand that all his life, their General had a very particular idea of what Europe should aspire to.

During the Second World War, when de Gaulle was speaking as leader of the Free French Forces before the Consultative Assembly in Algiers, on March 18th 1943, he presented a vision of a new, post-war Europe: "For the renewed Old Continent to find a balance that meets the ambitions of our age, it seems to us that certain groupings must be made there."

"The Channel, the Rhine and the Mediterranean would be like the arteries, with a close connection to the Orient and the Arab states, which legitimately seek to unite their interests," he added, inspired by broad, visionary horizons rather than conformist, dead-end policies.

De Gaulle, who founded the Fifth Republic, always opposed the narrow, shopkeeper outlooks of others who claimed to be building Europe but who were in fact killing it. "When you are dealing with Europe, and seeking to understand what it should be, you must always have in mind a picture of what the world is," he said at a press conference on July 23rd 1964.

He opposed mercantile ideology, and derided the European Coal and Steel Community, founded in April 1951, as "this mish-mash of coal and steel". He refused to join the ranks of the venal, realising that if building Europe were entrusted to swindlers, traffickers, purveyors and other financiers, it would endanger democracy, and by extension people's rights. "You do not integrate people the way you make chestnut purée," he said.

For de Gaulle - and the French political right has never forgiven him for these suspicions - the nearest thing to a captain of industry was a Mr. Moneybags. It was simply impossible to entrust Europe's destiny to sorcerer's apprentices and servants of capitalism, and chief among them, Jean Monnet, one of the architects of the European Community, a cognac exporter who passed himself off as a guiding light.

So de Gaulle, who was far more of a European than the credulous or cynical partisans of a so-called Euro-Atlantic community, opposed Europe being simply a commercial shell. He wanted a political edifice, a solid construction and not mere packaging.

And he would sometimes impose this construction against the will of his own political family, (including Michel Debré, who served as his Prime Minister ), and who were died-in-the-wool nationalists.

De Gaulle extended the Common Market to agriculture in 1962, after what he later described as "dramatic debates" in his book Mémoires d'espoir (‘Memoirs of Hope'). He was a pragmatist, and could sense what would be an inevitable evolution. But he knew how to contain it rather than espouse a theory of inertia by letting sleeping dogs lie.

Europe was worth every sacrifice, even abandoning sovereignty, on condition that it served a grand design. Which required it to be an independent power. This is what he meant by "a European Europe". It was far more than a tautology.

Europe should not trail behind America. Its eastern half should not be under the heel of the Soviets playing with the division of Germany. Europe should anchor Great Britain to the continent to avoid any blackmail by London. And Europe should not be subject to the markets' diktat. In de Gaulle's eyes, in the 1960s, states remained the best mechanism for avoiding such problems.

Then - because de Gaulle believed in a Europe he would never see in his lifetime - once the political plan had been implemented and the various nations had adapted and acclimatised, a time would come when fusion would be inevitable.

De Gaulle summarised his concept of the primacy of a political architecture that would stand against the insidious consequences of commerce and exchange rates at the aforementioned press conference on July 23rd, 1964. "Politics is action, that is, the sum of all the decisions taken, things done and risks accepted, all with the approval of a people," he said. "Only governments have the ability to do this and take responsibility for it. While it is certainly not forbidden to imagine that one day all the people of our continent will be one and that then, there could be a government of Europe, it would be ridiculous to act as if that day had come."

The following year, when he was interviewed on television between the two voting rounds in the 1965 presidential election, de Gaulle called for inter-European solidarity. He took a swipe at those who, without a true vision for European integration, were simply "jumping up and down in their chairs like young goats shouting ‘Europe! Europe!'" to no purpose (see video below, in French only).

But a little further in that interview, he explained he never advocated a Europe of "a collection of homelands", and went on to describe what should be built: "It will begin by being a co-operation, and perhaps later, by dint of living together, it will become a confederation. Well,I am quite happy to envisage that, it is not at all impossible."

Joschka Fischer, the next great visionary

De Gaulle said this time and again. He would have done it time and again when the time came. And the time was right a decade or so after the Berlin Wall fell. Europe's locks had been prised open. The Old Continent was cured of its hemiplegia and the former People's Democracies came back into the European fold.

While Germany betrayed de Gaulle when it reaffirmed its spineless attachment to Washington in June 1963 by adding a pro-American clause to the Élysée Treaty, it showed itself nearly 40 years later to be free, strong and responsible enough to pull the European chariot with France. It would prove this in 2003 when, with France, it opposed the war in Iraq instigated by George W. Bush.

In 2000, Joschka Fischer, then German minister of foreign affairs and perhaps the greatest visionary in government after Charles de Gaulle, proposed a powerful, enlarged and democratic Europe, finally united by an ideal based on reality. A European Europe standing on two pillars, its nation-states and its sovereign peoples.

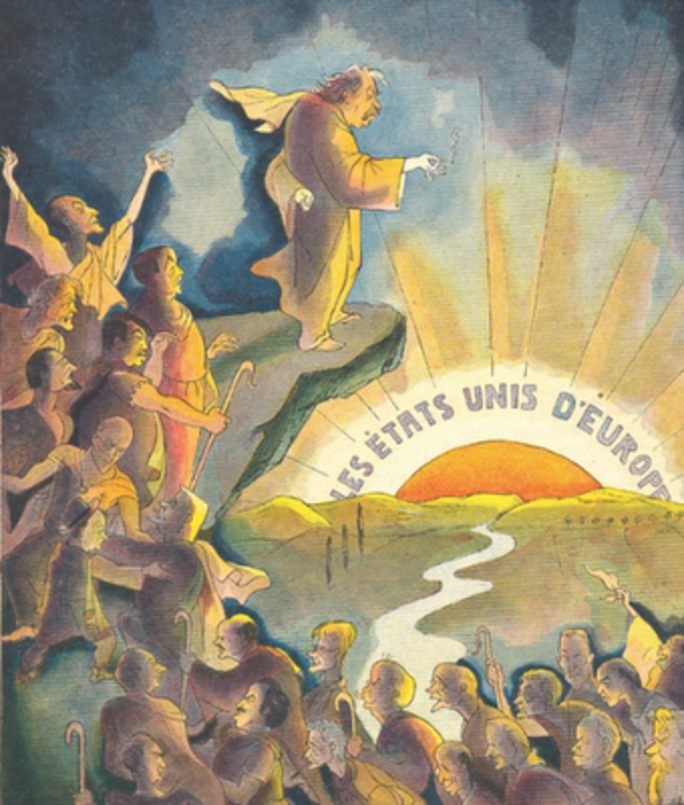

Fischer had judiciously understood the lessons, unlike Aristide Briand, credited with having been the first politician to put forward the idea of a European union in a speech to the League of Nations in 1930, who followed an idealistic vision.

The famous photograph of German Chancellor Helmut Kohl and French President François Mitterrand in 1984, standing hand in hand at Verdun, had created a closure for the past in great manner. And on May 12th 2000, Joschka Fischer's speech at the Humboldt University of Berlin, "From Confederacy to Federation: Thoughts on the Finality of European Integration", created an opening to the future. Europe must introduce institutional and constitutional reform to allow it to exercise its rights and ideals.

It was interpreted as no more than a federalist position that de Gaulle would have opposed. But this is wrong. It was a way of acknowledging changes which de Gaulle had previously wished for. The peoples of Europe were ready to take back the power that had been left too long to technocratic or financial tutors, to have an impact on the world's progress instead of simply cutting good deals.

A form of European public opinion was finally born when Augusto Pinochet was arrested in London on a request from Spanish judge Baltasar Garzon. Across the continent people took to the streets to protest against sending the former Chilean dictator back to his country, revealing a desire to go beyond milk quotas and towards a global ideal at last.

Europe was ready to put its weight behind preventing a clay-footed America from going to extremes, for reining in a vainly vindictive Russia, to civilise China's frenzied capitalism or for obtaining a fair agreement for the Middle East which would, as a result, aspire to imitate this Old Continent founded on its alliance between yesterday's sworn enemies, Paris and Berlin.

Jacques Chirac, then president, a prisoner of his "cohabitation" with Socialist Prime Minister Lionel Jospin - himself a prisoner of his own lack of historical substance - offered up an unworthy response to Fischer's speech. Speaking to the Bundestag on June 27th 2000, Chirac was only prepared to announce a preparatory consideration of the matter and a period of transition with the aim of restructuring institutions and reorganising treaties.

An inert and divided Europe would then suffer the full impact of the attacks of September 11th 2001 and the ensuing rage of America. A monotonous and democratic Europe would allow financial pressure groups to ingratiate themselves in the interstices of the Brussels bureaucracy. An unbalanced Europe would allow the prospering German economic giant to take the political lead amid all the inconsistency around it.

Now, ten years after the missed opportunity that Fischer provided to perpetuate de Gaulle's ideas, the wreckage is enormous. Like a headless chicken, France reacts in the most gormless way to Germany, still standing among so much ruin. The French Left accusingly cries "Bismarck": will it be "Hitler" next? The French Right, formerly Atlanticist, is now pro-Berlin and kowtows at the current master's feet.

And de Gaulle's question, which Fischer took up in his fashion in 2000, comes back like a boomerang, nearly 50 years after he addressed a cabinet meeting on April 17th 1962, following rejection of the Fouchet Plan for intergovernmental European structures. "Do we, or do we not, want Europe to be European? Do we, or do we not, want it to be subordinate to the United States?" asked de Gaulle, (today that should read "subordinate to Germany"). "Do we, or do we not, want the Common Market to be supplemented by a political organisation without which economic construction will ultimately decline?"

Instead of reviling or revering German Chancellor Angela Merkel - the new regent that Europe will once again allow to be imposed upon it because of its impotence - this would be the time at last to establish, collectively and democratically, a transcontinental, geopolitical plan. One that would herald neither the Vatican's Europe, nor a Yankee Europe, nor a German Europe nor a French Europe. To hell with that, it should be a European Europe!

-------------------------

English version: Sue Landau

(Editing by Graham Tearse)