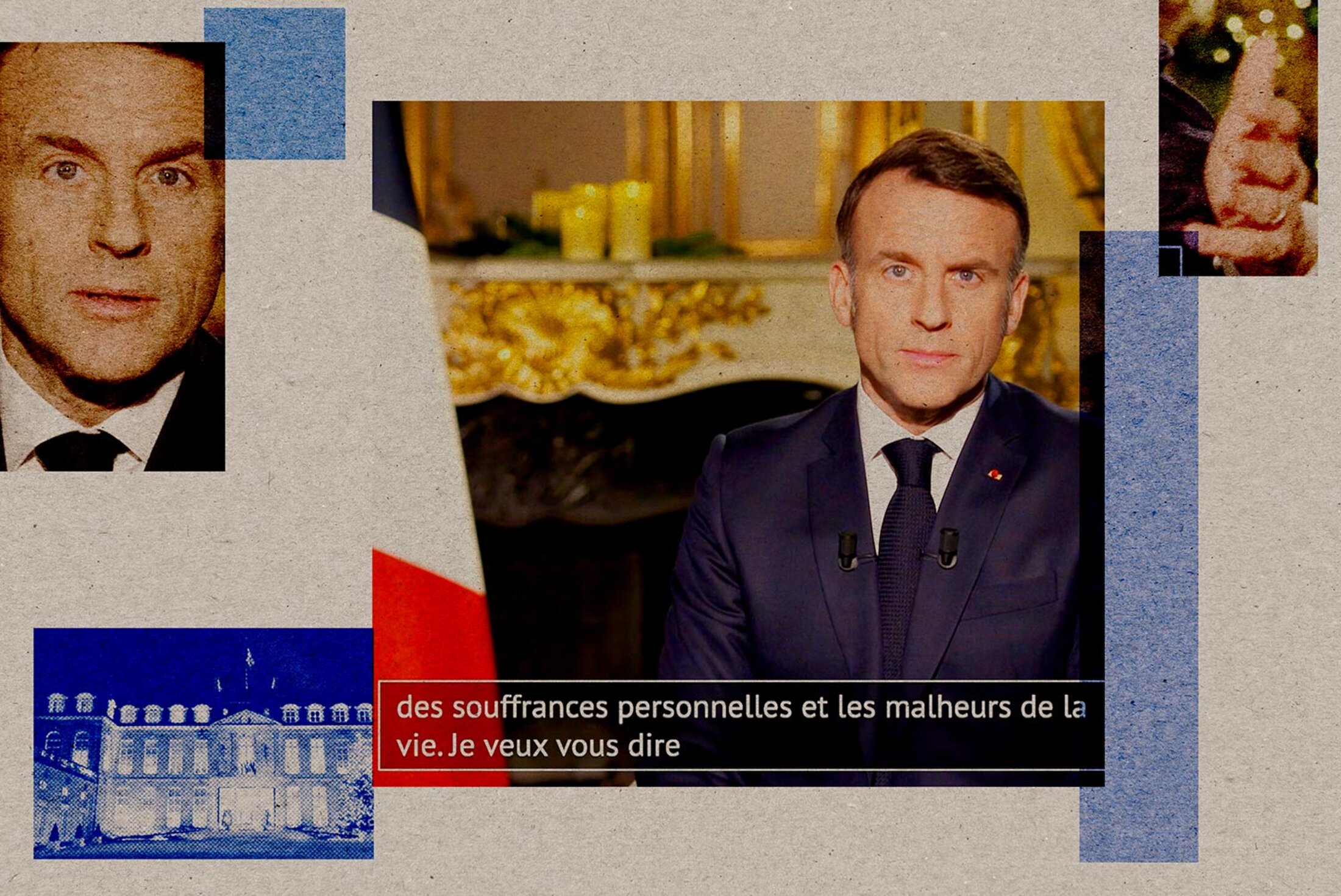

“Fuck it, two more years,” groaned the puppet portraying French president Jacques Chirac on the satirical puppet show Les Guignols de l’info. On a different timescale, young children have a less vulgar expression: “Just two more beddy-byes.” And the reaction of those who watched Emmanuel Macron address the nation on Wednesday December 31st? For the ninth and penultimate time since he was first elected, the president delivered his traditional New Year wishes to the French people on television. “Strength, independence and hope”, was his message from the Élysée, as he sat in front of a fireplace and a Christmas tree.

Is it the fatigue associated with the end of a term of office that has seemed to stretch on endlessly? Or is it the anachronistic nature of an annual tradition inherited from the days of President Charles de Gaulle, who introduced France's current presidential system in the 1950s? Whatever the reason, the current head of state’s speeches give an ever-growing sense of emanating from another dimension; from a galaxy where nothing exists, in which there are no lost elections, no vanished influence, and no calls from all sides for his resignation. In this parallel world depicted by the president at the end of each year “our country holds firm, through the strength of its institutions, its public services and its armed forces”.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

As he often does, and like his predecessors before him, Emmanuel Macron stared straight into the camera in a bid to bring some hope and optimism to the country. “Never have so many French people been in work” and “our inflation is one of the lowest in the euro zone”, he congratulated himself. “We must hold fast to what we cherish: humanity, peace, freedom”, he urged, saying he was confident that “we will succeed because we're French”.

Obsessed with the idea of not fading from the scene, and anxious not to end up like President Jacques Chirac ensconced in his palace, Emmanuel Macron has been seeking to identify a few subjects on which his voice still carries some weight. These are “structural” issues for the “long term”, for the “quarter-century ahead”, his entourage sometimes say, themselves never short of talking points. Three of these projects were cited on Wednesday evening as priorities for the year ahead: the launch of voluntary military service, the banning of social media for children under 15, and the completion of the end-of-life bill. “This year must be and will be a productive year,” the president promised.

Emmanuel Macron did not stop there. He is a president who has said – and said often over the past nine years – that he “shares” some of the “impatience” and “anger” running through the country. In his address he listed a number of “urgent” issues that “demand answers”, from crime and the cost of living to immigration and falling birth rates. It was a kind of general policy statement that will remain simply a wish; the pious hope of a head of state at the end of his time in office and who lacks a parliamentary majority.

No commitments made

In an address also coloured by the geopolitical situation, the head of state portrayed France as a driving force for Europe and its values. “Our world is growing harsher by the day,” he said, regretting the “return of empires” and the “challenging” of both the international order” and “stability”.

Here again, what was not said mattered more than what was. A narrative of a France taking the initiative and calling the shots sits uneasily with a list of recent diplomatic episodes: the trade agreement between the United States and the European Union, signed at the end of July, the peace talks in Ukraine, the imminent conclusion of the EU–Mercosur trade treaty – opposed by French farmers - the peace negotiations in Gaza, and so on. At a time when Paris’s influence is visibly shrinking, even the magic of the festive season is not enough to make a script placing French diplomacy at the centre of events ring true.

It is hard, then, to see this address as anything other than an exercise in convention. Élysée advisers had already warned the press: “There will be no announcements.” That promise was kept, unlike the one Emmanuel Macron made a year ago. “I will ask you to decide on certain decisive issues,” he had said back in his 2025 New Year address, opening the door to referendums during the year.

Twelve months on, the idea of a referendum is no longer on the cards. “Political instability” is to blame, argue those close to the head of state, even though he had made that pledge a few weeks after the government was brought down by a vote of no confidence at the National Assembly.

Echoes of François Hollande

With just months to go before municipal and senatorial elections, which are likely to confirm the decline of his own centrist political camp, Emmanuel Macron did not this time even mention the current state of democracy. Yet there would have been plenty to say on this issue, not least about the curious decision to appoint his most loyal supporter - Sébastien Lecornu - to the post of prime minister after two electoral defeats and two governments having been brought down by parliamentary votes. Alone before the camera, the president was not forced to justify himself. Indeed, when will he be, given that he increasingly avoids the press when travelling?

Conversely, the press is paying less and less attention to Macron, as parliamentary debates and the pre-presidential campaign increasingly occupy its thoughts. All this recalls the final months of the presidency of François Hollande (2012-2017), who had become a discredited head of state in whom few people any longer took an interest. The parallel extends even to the words chosen by Emmanuel Macron to refer to the 2027 presidential campaign, which will be the “first in which I will not be taking part for ten years”, he noted in Wednesday's address.

“Even so, I will be working until the very last second,” he promised, just as his predecessor had pledged on December 31st 2016. Meanwhile, in outlining an argument about “fraternity” and “kindness” during his address to the nation, Emmanuel Macron implicitly criticised the far-right and its racism. This comes towards the end of two presidential terms that have been marked by the historic rise of the far-right Rassemblement National (RN). He does indeed inhabit a different dimension.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter