Two French presidents, both from the Right albeit to a greater and lesser degree, have succeeded in stating what their leftwing predecessors did not know how to express. After Jacques Chirac, who in 1995 unlocked official French memory of German occupation in WWII and collaboration with the Nazi regime, Emmanuel Macron has now unlocked the cupboard containing the hurt and the secrets of the Algerian war of independence.

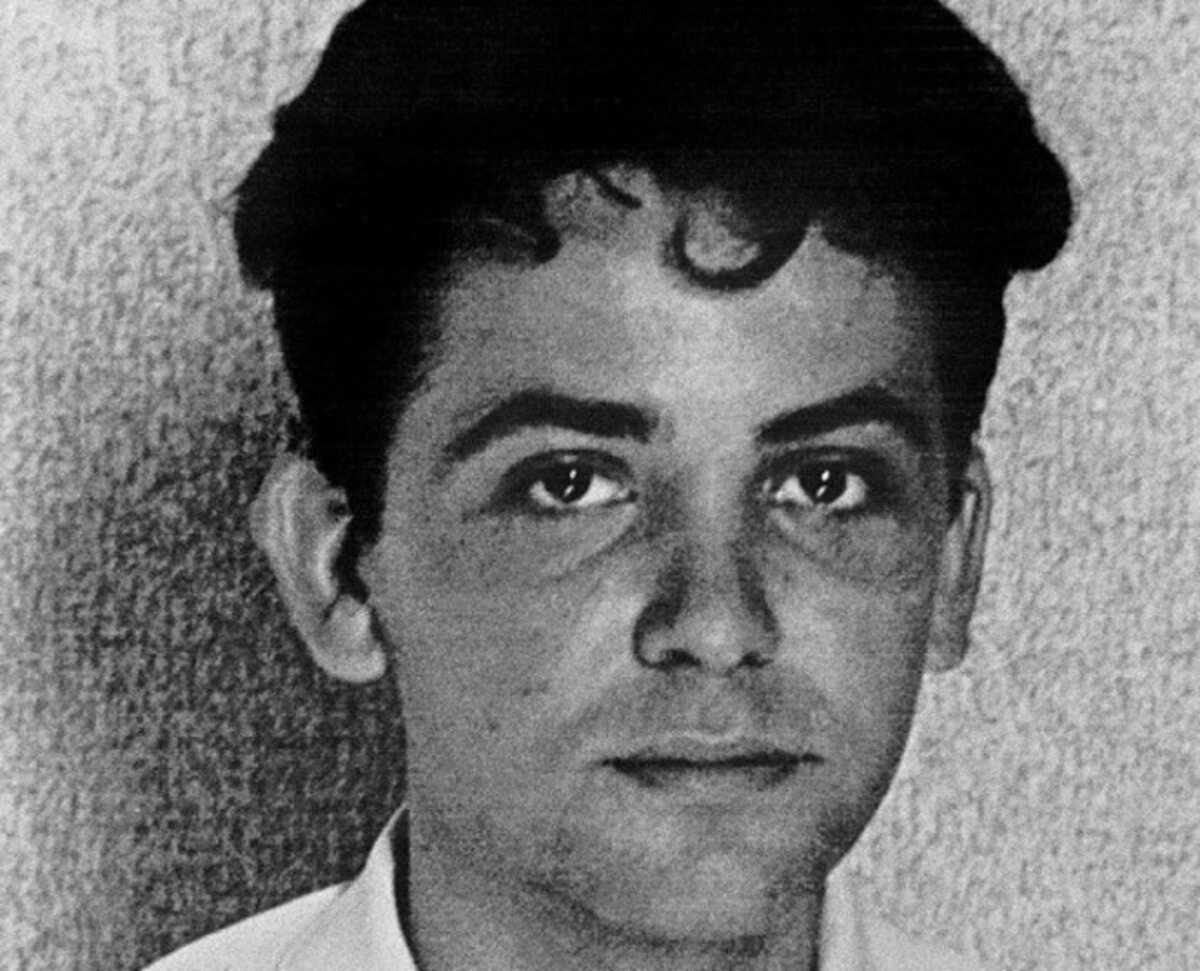

Through the tragic case of the young Algerian Communist militant Maurice Audin, arrested by the French army in Algiers on June 11th 1957, when he was tortured and subsequently either executed by the military or died from the wounds inflicted under torture – the incertitude about that remains – the eighth French president under the Fifth Republic has publicly recognised the existence of a “system instituted on a legal basis, the special powers” which, he added, “were the unfortunate breeding ground for sometimes terrible acts, including torture”. For all those who for a good 60 years have been engaged in a combat for the truth, that recognition is a victory that recompenses their courage, loyalty and doggedness.

Of course, we know this truth, as Michèle Audin, a writer as much as she is also a mathematician, like her father, explains in the wonderful book she dedicated to him Une vie brève (A brief life), published in 2013. “Maurice Audin was 25-years-old in 1957,” she wrote. “He was arrested during the battle of Algiers, he was tortured by the French army, he was murdered. His pretended escape was organised and the traces of his death were got rid of.”

What we have asked for is that by acknowledging this, the French state faces up to it with all its consequences, by admitting that the war in Algeria involved an institutionalisation of torture, in a perdition that damns the three powers that are the legislature, the executive and the judiciary.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

As welcome as it is tardy, the statement from the summit of the state about the truth of the case of Maurice Audin at last opens up a path to a reconciliation of Algerian and French memory of events, so much this traumatic past is still present at the heart of our two peoples, passed from generation to generation. The president’s declaration is an appeal to them, in their wounded diversity, to together carry out this task of truth and memory. A gangrene for France’s republic, the systematic use of torture – and also the arbitrary arrests, the disappearances, the internment camps and the violence used against the civil population – has led to a separation between Algeria and France which has hurt both, leading to a wrenching apart and certain radicalisations, all of which might have been avoided if it wasn’t for the blind stubbornness of the French government.

On this side of the Mediterranean, millions of us, across at least three generations, are party to this common story: the descendants of Algerian workers in France many of who, at the time, espoused the nationalist cause; those who are called the “pieds noirs” – black feet – the nickname for the Europeans who settled in Algeria and who were far from all being colonial oppressors – Maurice Audin, indeed, came from one such family; the families of Sephardic Jews for who Algeria is their ancestral land; the community of harkis, the native Algerians who fought with the French against the independence movement, and who are victims twice over after subsequently being rejected and despised by both sides. There are also all the families who live with the phantom-like silences of parents who served in the French army, either called up or as professional soldiers, duty-bound to fight a war in which France was morally defeated.

But the consequences of Emmanuel Macron’s declaration concern our present and future as much as the history of this illegitimate and disastrous eight-year colonial war, from 1954 to 1962, which led to the undoing of France’s Fourth Republic. It was a war that ended with Algerian independence, four years after the collapse of the Fourth Republic in 1958, battered by the hardliners in favour of continued French rule. It indeed serves as an alert of the dangers of every state of exception which, under the pretext of security threats, removes democracy from its usual legality, and as a result from its democratic course.

The president’s statement underlines that it was a law “voted by parliament in 1956 [which] gave the government carte blanche with which to restore order in Algeria”, and that it was this law of “special powers” – powers that were uncontrolled and with which every excess was allowed – notably gave the police and the army “the system called ‘arrest and detention’ at the time, which authorised the law enforcement services to arrest, detain and interrogate every ‘suspect’ in the aim of a more effective campaign against the opponent”.

We can hope that this historic pronouncement will henceforth prompt a reflection by parliamentarians who, in face of terrorist attacks these last years, agreed to chip away at the state of law with exceptional measures, arguing a provisional emergency which, after subsequently becoming permanent measures, enduringly weaken individual rights before the reason of state. It cannot be forgotten that measures of the state of emergency introduced under the presidency of François Hollande, which were then enshrined in common law under that of Emmanuel Macron, used as their reference point a law adopted in 1955 to combat the Algerian independence movement – and which was extended one year later by that which allowed for the “special powers”.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

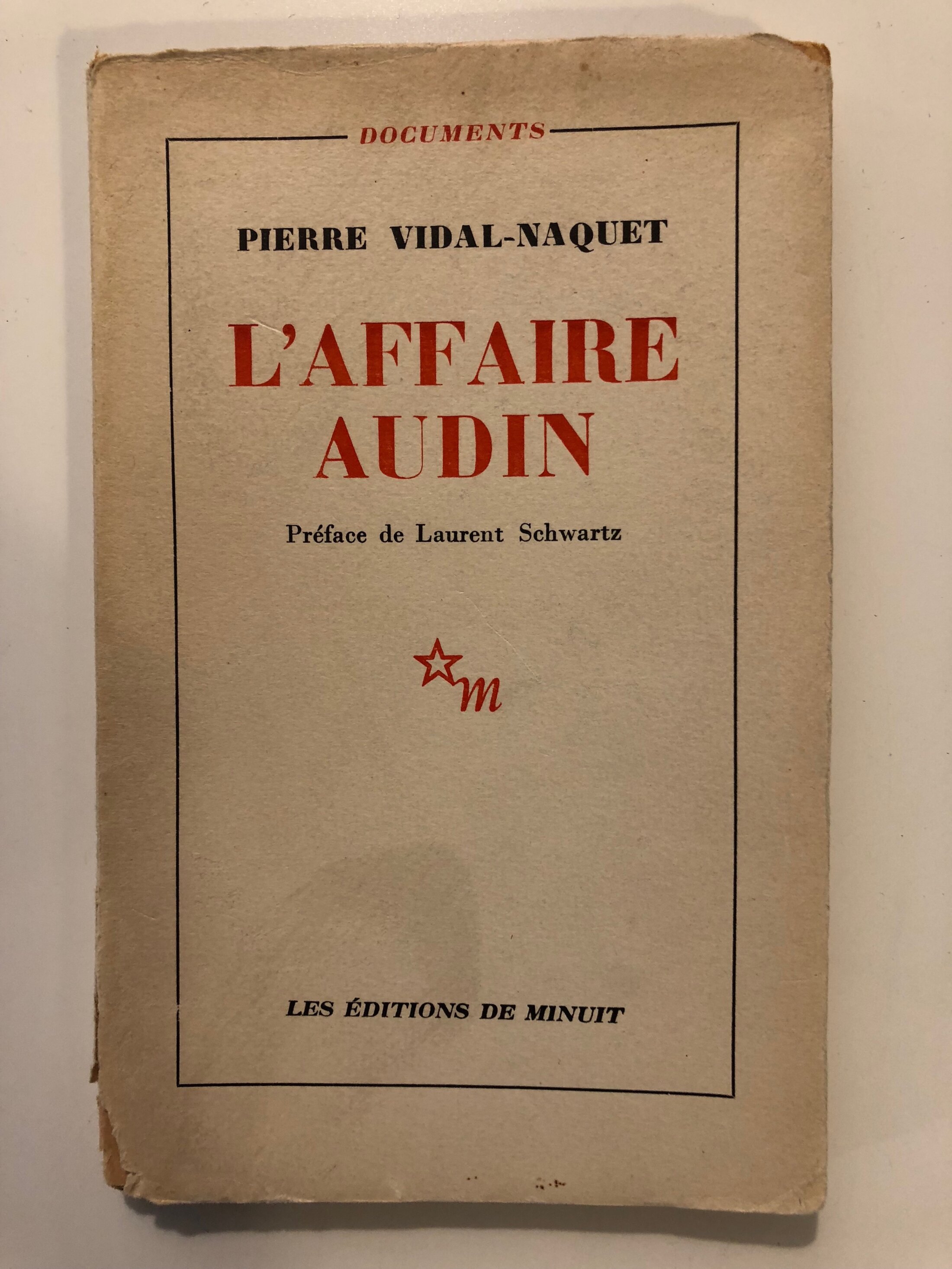

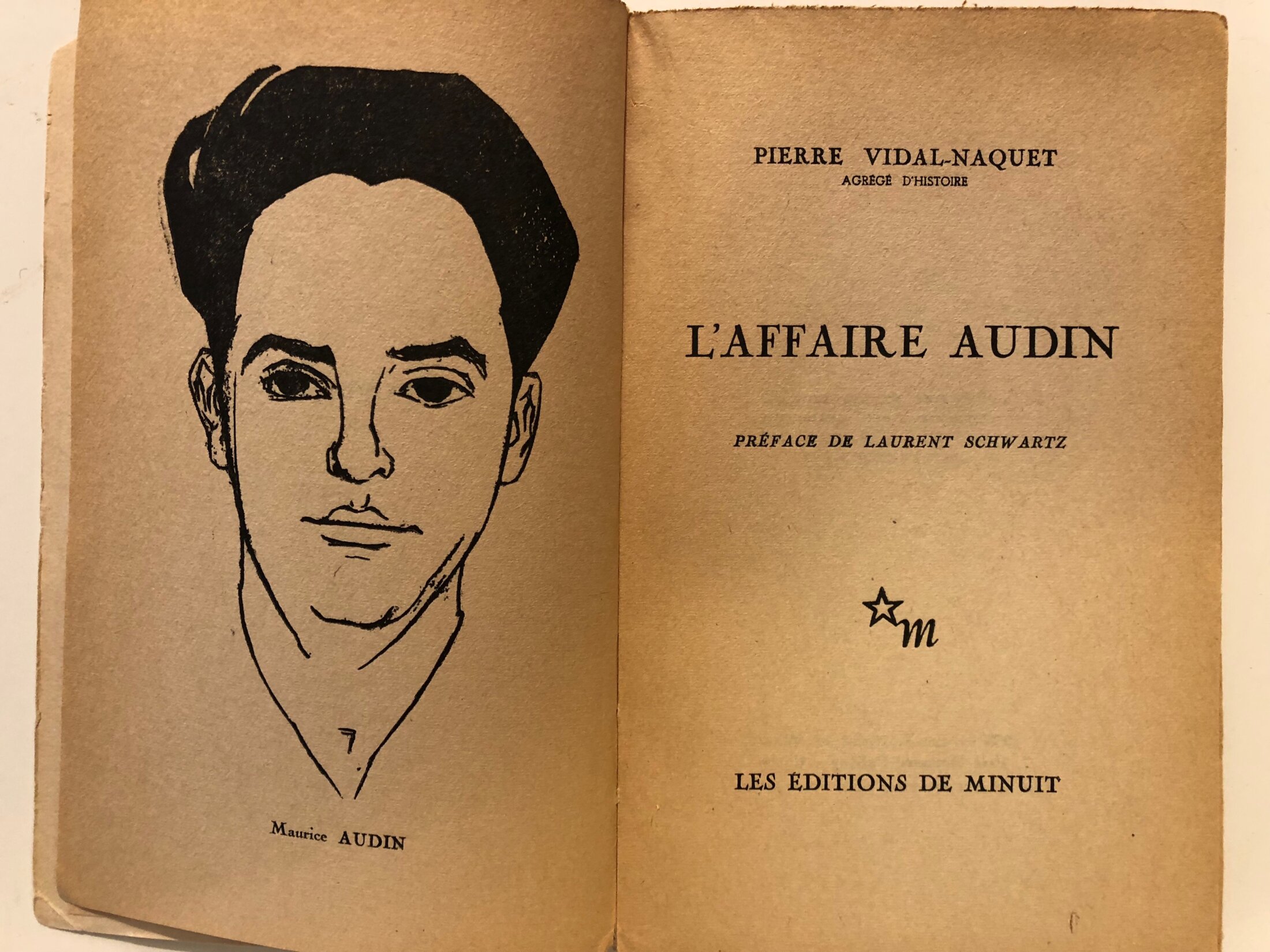

But concerning the case of Maurice Audin, the statement goes further. It establishes that, in the absence of sufficient vigilance by those who govern, democracies can submit to practices that systematically violate human rights even to the point of this totalitarian crime of torture, this negation of the humanity of those who fall victim to it. It is not by chance that this remarkable statement begins with a highlighted quote from the late French historian Pierre Vidal-Naquet, responsible for documenting the institutionalisation of the use of torture in his 1972 work La Torture dans la République and whose initial engagement against the war in Algeria was his 1958 book about the killing of Maurice Audin, entitled L’Affaire Audin.

“Certainly, torture has never stopped being a crime before the law, but it developed because it remained unpunished,” declared Emmanuel Macron. “And it remained unpunished because it was conceived as a weapon against the FLN [the Algerian National Liberation Front] which launched the insurrection in 1954, but also against those who were considered its allies, militants and partisans for independence; a weapon considered to be legitimate in that war, despite its illegality. By failing to prevent and punish the use of torture, successive governments placed in peril the survival of men and women held by the law enforcement services. However, in the last resort it is with them that lies the responsibility of ensuring the safeguard of human rights and, firstly, the physical safety of those who are detained under their rule.”

A duty of truth

“It is important that this story is made known, that it be looked upon with courage and lucidity,” added Emmanuel Macron. It is this courage and lucidity that was lacking in François Mitterrand, a tutelary figure for the French Socialist Party who served 14 years as president, from 1981 to 1995, whose attitude of staunch denial paralysed socialist administrations on these memorial issues, always so alive and pertinent. That was true for numerous socialists who surrounded Mitterrand in power and who had joined the cause against the war in Algeria as their first militant commitment – notably Pierre Joxe and Michel Rocard.

From Chirac to Macron, two doors kept locked by Mitterrand have given way. The latter not only refused to face up to his allegiance with the far-right in his younger years, and later with the collaborationist regime of Vichy in German-occupied France, when he was awarded the Order of the Gallic Francisque by the regime’s head, Marshall Philippe Pétain. Mitterrand also refused to face up to his past as a minister in government during the 1950s, during the Algerian war of independence, actively espousing policies of repression and denying the right of peoples to self-determination in order to maintain at whatever cost the colonial empire. It was only after his death, for example, that official archives were to confirm to what degree, when he was justice minister from February 1956 to May 1957 under the government of Guy Mollet, he was uncompromising, agreeing to 45 executions of Algerian nationalists, refusing to pardon almost all of those facing the death penalty.

For far too long the truth about the war in Algeria, its crimes and injustices, was officially denied or covered up. To the point where it was only in 1999 that French parliament recognised the military campaign, previously officially referred to as “operations carried out in North Africa”, was a "war", 45 years after the beginning of the FLN insurrection which was prompted by the French government’s refusal to allow the Algerian people self-determination.

With the events at last recognised by the French head of state, a path has been cleared for a deeper work of reflection on the period by Emmanuel Macron’s decision “to encourage the historic work on all the [people who] disappeared in the Algerian war, French and Algerian, civilians and military” through a move to open up “for unrestricted consultation all the state archives concerning this subject”.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

In his preface to Pierre Vidal-Naquet’s L’Affaire Audin, the pioneering French mathematician Laurent Schwartz said of Maurice Audin that, “If he was a partisan, it was for the truth only”. There were echoes of this original struggle, the principal protagonists of which were mathematicians and historians, in President Macron’s statement: “It is the duty of truth which is incumbent upon the French republic, which in this domain as in others must lead the way, for it is by truth alone that the reconciliation is possible and there is no liberty, fraternity and equality without the exercise of the truth.” A people must know how to look at the truth in the face, however painful it is to do so, for itself, its honour and its grandeur.

While obviously supported by numerous militant energies of goodwill, including from the French Communist Party of which Maurice Audin was a member and also the League of Human Rights, which has been constant in its engagement, two loyal figures have unfailingly championed this combat for justice. One is the outstanding mathematician and member of parliament for Emmanuel Macron’s ruling LREM party, Cédric Villani, awarded the prestigious Fields Medal, who took upon himself this duty of truth, in the continuation of his predecessors who include the late Laurent Schwartz, Henri Cartan and Gérard Tronel, and others still present like Michel Broué (president of the Amis de Mediapart), who Villani succeeded as head of the Sorbonne university’s mathematics research centre, the Institut Henri-Poincaré.

The other is the historian Sylvie Thénault, a research director with France’s national scientific research centre, the CNRS, who, in the wake of Pierre Vidal-Naquet, played a key part in establishing the precision of Emmanuel Macron’s statement regarding the “system” which allowed the killing in all impunity of Maurice Audin and so many others. Her accounts of the role of French magistrates during the war in Algeria and, more recently, on the arbitrary detentions carried out under French rule are regarded as works of reference.

As also is French historian Benjamin Stora’s 1998 landmark book La Gangrène et l’Oubli. Our governments, including the present one, cannot be reminded enough of how, without freely conducted academic research that is not dependent upon the logic of commercial returns, this moment of truth might never have been reached.

Pierre Vidal-Naquet liked to describe the movement of his generation against the war in Algeria as “Dreyfusiste” (in a reference to the infamous ‘Dreyfuss affair’, involving the wrongful accusation, driven by anti-Semitism, of treason against French army captain Alfred Dreyfus), underlining how much it involved the defence of individuals in face of the arbitrary and lies. If there is one lesson to retain from this long combat engaged by members of civil society, it is that one must refuse to be indifferent to others and to the world, and be actively concerned for the plight of men and women struck by injustice. That sentiment was embodied to the end by the Audin family’s lawyer, Roland Rappaport. Just days before his sudden death on June 26th 2017, he wrote to Emmanuel Macron (see the full text in French here) to bring to his attention the existence of documents he had discovered in the archives of his colleague Maurice Garçon, and which detailed that Maurice Audin had died while in the hands of French parachutists.

The Audin affair was for the anti-colonialist movement what the Dreyfus affair was for those who fought against anti-Semitism: the defence of all through the cause of one alone. On the jacket of the book by Pierre Vidal-Naquet, which was published one year after the disappearance of the young mathematician, Jérôme Lindon, head of publishing company Les Éditions de Minuit, included an extract from the 1898 book Preuves, a compilation of articles by French socialist leader Jean Jaurès (1859-1914) which argued the innocence of Alfred Dreyfus. It began: “Yes, which institution remains standing? There remains only one: it is France itself. For a moment, it was taken by surprise, but it recovered, and even if all the official flaming torches were extinguished, its clear good sense can still dispel the night.”

If France is standing upright this week, it is thanks to all those who led this long and patient anti-colonial combat for which Maurice Audin was both an emblem and a martyr.

-------------------------

- The French version of this op-ed can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse