On Saturday, November 6th 2004 Laurent Gbagbo, the president of Ivory Coast, was in his office at the presidential residence in Abidjan where he was drafting a speech he intended to deliver to the nation on television that evening.

According to information he had received, the country's armed forces – the Forces Armées Nationales de Côte d’Ivoire or 'FANCI' - were set to conclude 'Operation Dignity' later that day. This offensive, launched on November 4th, was aimed at reclaiming the northern part of the country, which had been occupied for two years by a rebel group known as the Forces Nouvelles. After a series of aerial bombardments of enemy military positions, at least two elite FANCI units had already reached the outskirts of the rebels’ stronghold, Bouaké, that Saturday morning. They had encountered no resistance.

The Ivorian president was particularly confident because both ONUCI, the United Nations peacekeeping mission in Ivory Coast, and France, which had deployed the 5,000-strong Operation Licorne (see box below) under a UN mandate, had allowed the military operation to proceed - even though in Paris an angry President Jacques Chirac had tried to prevent the assault. In his speech Laurent Gbagbo was therefore preparing to announce the liberation of Bouaké. He also planned to call on the rebels to disarm, something they had always refused to do. “Peace isn't far off,” he assured several of his friends the previous day.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

But the president never got to deliver his address. At 1.20pm, everything went wrong in Bouaké. Two Sukhoi SU-25 aircraft flying on behalf of FANCI but piloted by Belarusian mercenaries flew over a unit from Operation Licorne's GTIA 1 (Groupement Tactique Interarmes). One of the planes fired its rockets. Nine French soldiers and one American civilian were killed, with 38 others wounded.

This act marked the beginning of one of the most troubled and bloody episodes in the history of Franco-Ivorian relations since 1960 when the West African country achieved independence from its colonial ruler. Without waiting to determine whether his men had been deliberately targeted or were victims of a mistake, and without consulting the UN's ONUCI, France's General Henri Poncet, commander of Operation Licorne, ordered the destruction of the two SU-25s with missiles shortly after they landed at Yamoussoukro airport at 2.20pm.

Officially this strike, which injured some Ivorian soldiers, took place following orders from President Chirac to prevent any further action against the French forces.

This swift and brutal retaliation shocked Laurent Gbagbo, already reeling at the news from Bouaké, as well as the French ambassador in Abidjan, Gildas Le Lidec. The diplomat was surprised that Jacques Chirac could react so quickly on a Saturday and doubted that it was he who had given the order. He feared reprisals against the 15,000 French nationals living in the country.

'We immediately knew things were going to get out of hand'

His concerns were well-founded: the atmosphere between Paris and Abidjan had already been tense ever since the attempted coup by the rebel group Forces Nouvelles in September 2002. Massive demonstrations had been organised several times in Abidjan to support President Gbagbo, but also to denounce French interference, with France being accused of complicity with the rebels.

Movements such as the 'Young Patriots' had emerged, capable of quickly mobilising vast crowds. “Once the retaliation had been decided upon, we were aware that a process with serious consequences for the [Licorne] force and expatriates had been set in motion,” General Jean-Paul Thonier, the second-in-command of Operation Licorne, later testified before a French judge investigating the background to the deaths of the French soldiers.

Indeed, the news of the destruction of the SU-25s spread rapidly, much faster than that of the deaths of the French soldiers. It quickly circulated around the university residences in Abidjan, provoking anger and confusion. “We immediately saw that things were going to get out of hand,” recalled General Luc de Revel, who commanded France's 43rd Marine Infantry Battalion (BIMa), stationed in Abidjan under the command of Licorne.

He was ordered to seize control of Abidjan airport, located in the southern part of the city, in the commune of Port-Bouët. For the French military, this airport was a “key asset”. Not only was it located right next to their own base, but it would be crucial for receiving potential reinforcements and conducting any evacuations.

After exchanges of fire, which resulted in casualties among the Ivorian soldiers, and negotiations with the FANCI air detachment stationed there, the French, who numbered around 300 soldiers in Abidjan, managed to secure the site by late afternoon.

However, very soon they had to face thousands of protesters wanting to dislodge them. The clashes and chaos lasted for ten hours. The French soldiers fired tear gas grenades, shot rubber bullets and aimed warning shots above the crowd, General de Revel explained.

“We also had to fire a few direct shots in return,” he explained, in order to protect “one of our soldiers”. His men deployed a similar tactic about a mile further away at the Akwaba junction, to block the road leading to the French military base and the route towards the airport. A genuine battle took place there as well.

It was night, and in the sky, we saw what looked like lasers. We thought it was the Ivorian army guiding us. We applauded, we sang...

Around 8pm a new escalation occurred: General Poncet ordered the bombing of the helipad at the presidential palace in Yamoussoukro, a highly symbolic location where FANCI combat helicopters were stationed. At least 16 people were injured, and nearby homes as well as the palace were damaged.

This operation, based on dubious strategic and political foundations, had an immediate effect: it ratcheted up the tension even further. Many Ivorians now suspected the French of having found - or even created - a pretext to destroy their air capability and prevent them from gaining the upper hand over the rebellion. Ultimately, they believed it was a plot to overthrow President Gbagbo. On the other side, most of the French military personnel thought the Bouaké attack was deliberate and that the popular mobilisation they were witnessing was part of a well-prepared plan.

As the evening wore on, calls for “resistance” grew in number. Charles Blé Goudé, one of the leaders of the Young Patriots, urged his fellow citizens on Ivorian Radio and Television (RTI) to “liberate the airport”. He spoke of “dying with dignity” rather than “in shame”.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

With night now having fallen, thousands of people left their homes to swell the ranks of those already protesting. Some had heard the calls to take to the streets, while others, shocked by the actions of the French army, needed no prompting to react. “The patriotic spirit resonated within each of us,” recalls one Abidjan resident, who was a student at the time.

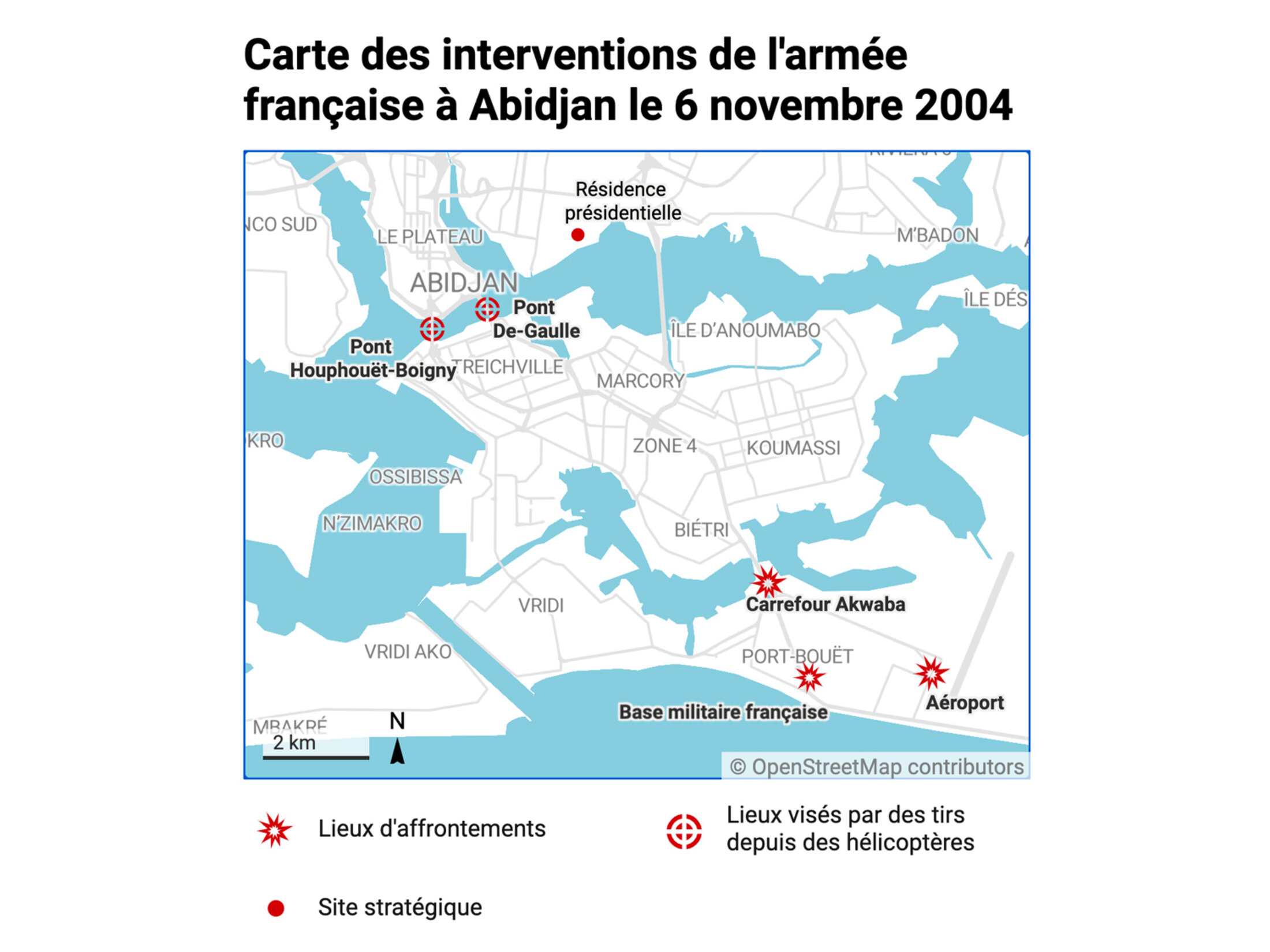

He had headed towards the presidential residence with the idea of protecting Laurent Gbagbo. Thousands of other residents from the northern part of the city made their way towards Port-Bouët, crossing the Charles-de-Gaulle and Félix-Houphouët-Boigny bridges that span the Ébrié Lagoon.

At 11.45 pm, French helicopters were deployed to stop the advancing crowd. In what resembled a war scene, they strafed both sides of the two bridges and then targeted the bridges themselves, also engaging in “a barrage of shooting” against vehicles. “It was night, and in the sky, we saw what looked like lasers. We thought it was the Ivorian army guiding us. We applauded, we sang,” recalls Guy-Constant Neza, another witness who was a student at the time.

When he was about a kilometre away from the Charles-de-Gaulle bridge, Guy-Constant saw a wave of people running in the opposite direction. Among them was a friend from childhood who shouted at him: “Don’t go there, there’s death, the French are shooting at the bridges, people are jumping into the water!”

“The shots were crosswise, in order to signal that people could no longer go across,” explains General de Revel. “The aim was to create a kind of curtain of iron and fire.” He adds: “It's possible that, at first, a car was hit, as well as one or two protesters, but it was never about firing on the crowd.”

A report broadcast weeks later by French television station Canal Plus painted a more horrifying picture. “Even isolated protesters were targeted. The few cars heading south in the city were shot at on sight. [...] Not a single protester fired a shot,” it stated. Witnesses told Amnesty International that they saw several people hit by the gunfire. Others described massive and dangerous stampedes caused by the shooting.

In total the helicopters, operating until 7.30am, fired more than 400 20mm shells, according to the French army, which took complete and final control of Abidjan airport around 2am.

'I want dead Ivorians'

Today, General Georges Guiai Bi Poin, a former student of the École de Guerre war college in Paris and commander of the Abidjan Gendarmerie School at the time, expresses his outrage at this aerial intervention. He points out that the French military base was about ten kilometres away, quite far from the scene. “If we, the Ivorian gendarmes and police, had been allowed to manage the situation, we could have stopped the crowd at Treichville,” he says, referring to a neighbourhood situated between the two bridges and Port-Bouët.

“So if the situation had been allowed to unfold between the crowd and us, meaning among Ivorians, nothing serious would have happened. But the French didn't have that mindset,” he asserts. “It was more than a law enforcement operation. It was a form of mass rioting, partly encouraged by the government or by those who represented it on radio and television,” comments General de Revel.

That night, groups of individuals looted and vandalised the properties of French nationals, targeting French interests and symbols, terrorising hundreds of families in certain neighbourhoods. This was despite the fact that the Young Patriots' Charles Blé Goudé had said in his televised address: “I'm not asking you to go and attack the poor French who are at home and have nothing to do with the situation.”

The following day, one source reported three protesters shot dead near the airport, while another instead spoke of six deaths. The Port-Bouët hospital said it had treated several dozen injured, some in a serious condition. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) recorded more than 410 injured.

You don't kill French soldiers with impunity.

The toll would doubtless have been higher if General Luc de Revel had agreed to fire upon and destroy FANCI aircraft (two SU-25s and two MI-24 helicopters) parked in a hangar at Abidjan airport. The officer disobeyed this order given by General Poncet because the building also housed a massive stockpile of ammunition. A missile attack would have caused significant material and human damage, he calculated.

He and his superior clashed “very fiercely” on this point. To justify his position, General Poncet told him: “I want dead Ivorians.” Reprimanded twice during the night of November 6th to 7th, General de Revel finally had the aircraft neutralised with sledgehammers and axes around 4am.

Why such a desire for destruction? “I believe the Bouaké bombing provoked psychological shock and a sense of betrayal in General Poncet,” was General de Revel's subsequent analysis.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

While President Chirac disapproved of the FANCI offensive, the French military, who “generally appreciated that the FANCI were likely to succeed”, had a “more permissive attitude” on the ground. “General Poncet did not seem opposed to Operation Dignity, but he basically told the FANCI, 'Be careful, lads, don’t touch a single hair on the heads of French forces',” General de Revel recalls. “Perhaps there were also hostile reactions in Paris - it's known that the phone conversation between Chirac and Gbagbo on the eve of the offensive was very sharp, even violent - and there was a lack of sufficiently nuanced geostrategic thinking to prevent our response from leading to widespread disorder.”

While the shocked citizens of Abidjan counted their dead and wounded, there was satisfaction in Paris. The Licorne forces had shown that “you don't kill French soldiers with impunity”, declared General Henri Bentégeat, the French Chief of the Defence Staff, on TV5 television on November 7th. “We had to fire a number of warning shots, and we may indeed have injured or killed a few people,” he admitted, likening all the protesters to “looters”. But it wasn’t over yet. Three more days of conflict were to follow.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here. Other parts of the series (in French) can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter