In order to understand the task of translation for the United Nations (UN), it is necessary first to take a closer look at “the contraption” (in French, “le machin”) as it was called by Charles de Gaulle, who was not, in a formal sense, all that wrong. Indeed, the “contraption” is a complex machine with multiple cogs which, in local idiosyncrasy, is called “the United Nations system”, and which includes:

- The United Nations Organization, subdivided into principal organs (the Secretariat, the General Assembly, the Security Council, the International Court of Justice etc) and subsidiary organs (the major commissions, the international criminal tribunals – such as that for Rwanda or the former Yugoslavia – peace-keeping missions, etc.);

- Funds and programmes, for example UNICEF;

- United Nations bodies: research and training institutes, or others (for example, UN Women);

- Related organizations;

- Regional commissions;

- Specialised institutions, such as the World Health Organisation.

This is just a rapid snapshot, which doesn’t mention other, finer cogs with more romantic names and which are better adapted to the uniformed guard who filters those who enter the 17-storey building that houses the translation services, or the electronic badge that controls the opening of any and every door; the “Docs Control” (the Documents Control Unit which controls the documents, which sets the date of their publication and which ensures the follow-up), or the “Fifth Commission” (which manages budgetary affairs).

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The organisation chart, then, is relatively complex, but the complexity regarding the process of translations is a notch above. Depending on which language is involved, these different entities are not designated in equivalent terms and do not necessarily concern the same realities. In English, for example, no difference is made between what in French is described as the Nations unies (the “united nations” which are the member states of the Organization) and what in French is called the Organisation des Nations unies (the United Nations Organization); both are in English called the “United Nations”.

As we know, the French language is historically the traditional tongue of diplomacy, and 'UN French' strives to keep the degree of precision with which it is due that status, but for the translator this often raises problems. All the more so because the authors of the documents in question don’t necessarily know the onomastics of the UN and that also, if they write their reports in English, they are not always of English mother-tongue which adds further to the difficulties of the process.

Let’s return a moment to the "diplomatic" aspect which is inherent to every translation within the United Nations. While a large number of documents and reports that require translation have no confidential nature regarding politics (such as documents concerning internal management), they are all translated in accordance to the same methodology. And that, understandably, applies in particular to the choice of the terms which are used, and which are often arrived at according to political criteria.

A concrete example of this: a report written in English uses the word “riots”. The translator cannot decide on their own whether this should, in French, be translated as émeutes (as appears in the Robert&Collins dictionary, for example) or manifestations, or troubles etc. The translator is required to consult a source to discover how this term was officially translated in the precise context of the report –for it’s not because “riots” was translated as émeutes yesterday in a given context that this translation is correct in another context. So the translator will dig deep into the huge data bank of the Organization, with the help of different search engines, making sure to define the subject both historically and geographically (for example, using keywords “riots”, “France” and “1997”).

In general, just as when using Google, several hundreds of thousands of results appear, and which don’t all have the same degree of accuracy. This hierarchy of sources is also taken into account in the methodology of UN translations. At the top of the scale, there are the reports from the General Assembly, and when a term has been translated in one particular manner (in a given context, obviously), the translator cannot change that. The translator must therefore use what has come before to the exclusion of any other term. Also, the official value of the translation in question decreases according to the hierarchical importance of the body that produced the original document; broadly, a letter by the UN secretary general carries more prescriptive weight than a report on replacing office equipment.

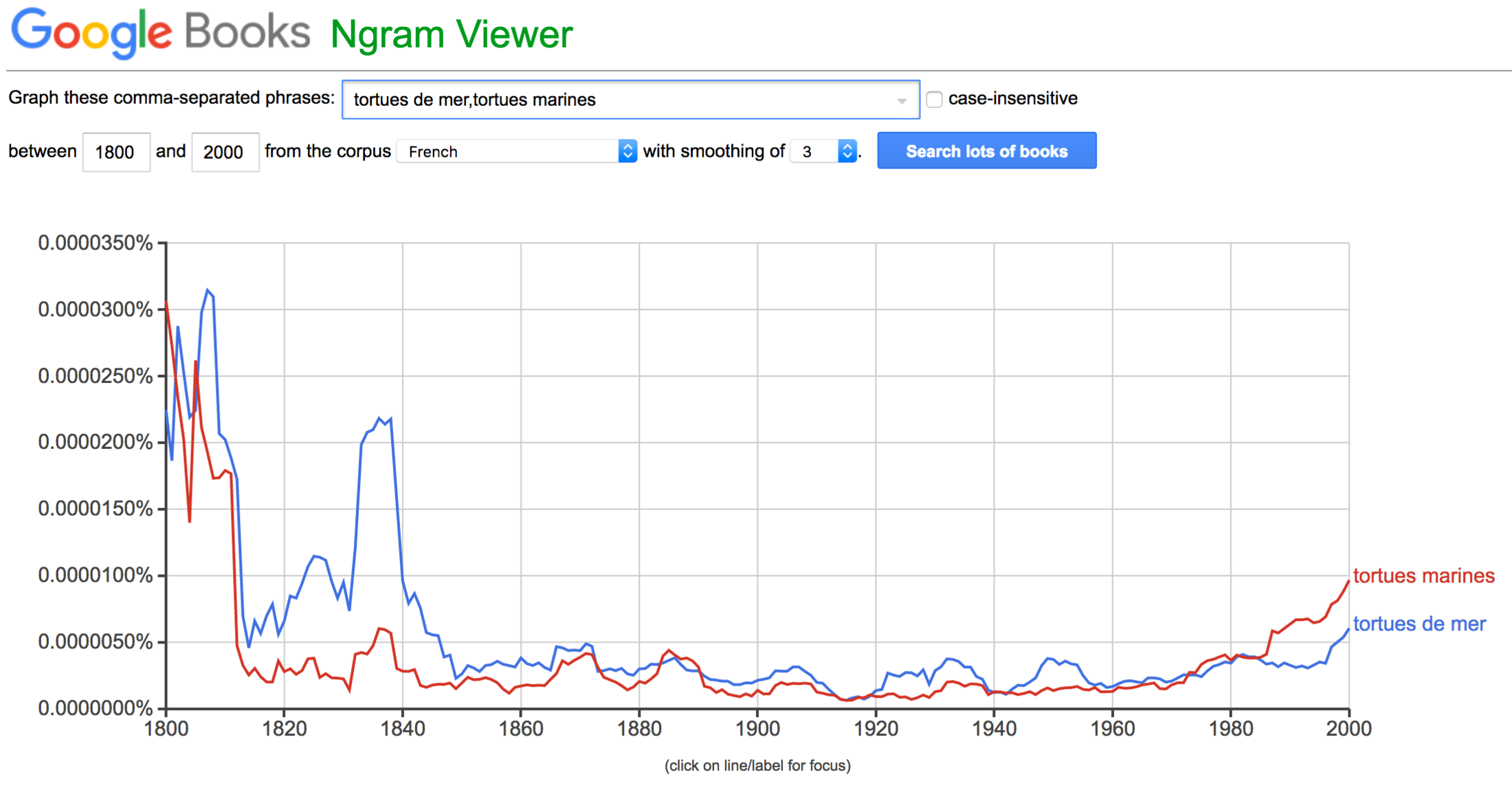

All that seems quite normal, and it appears even logical to proceed in this manner, but in the event this constraint serves to transform the act of translating the least sentence into a titanic job of research. You will look at the words “sea turtles” and you know that in French this is tortues de mer, but you nevertheless have to check in the data base to see what comes up. And you will have done well to do so, because the official translation turns out to be tortues marines, and that with tortues de mer you got it all wrong. What’s more, a search of Ngram Viewer shows that while historically tortues de mer predominates, tortues marines appears to have the upper hand in literature published in French since 1985 (see the chart below).

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The other advantage of this uniformity of terms employed is that the reports, which often run to 40 pages and sometimes more, have to be translated very quickly (on average within the two or three days after reception). They are therefore divided up between four or five translators, who will coordinated on the source-checking of terms in order to homogenize the final text. Correctors will subsequently check over and smooth the text. At the normal rate, the French translation services at the UN must every week translate 1,000 pages, each made up of 330 words, but at times of crisis (which means just about all the time), that output easily rises to 1,500 pages – a weekly volume equivalent to War and Peace.

Given these constraints, which are not only lexical, one better understands why reading UN reports can be indigestible, despite all the efforts of the translators to write in fine French, which they manage to do very well. But that is not the issue. The issue, if there is one, is about the prestige associated with “a certain image of France” which, according to one’s point of view, adorns or clutters up what one might call “official French”. For indeed, this French resembles nothing that a French-speaking person is used to reading. “Anthropomorphisme”, for example, rules supreme.

One regularly comes across phrases like La reprise de la conférence a décidé que…(“the resumption of the conference decided that…”) which means that a new conference was held and that its members decided that… When in English the phrase “draw someone’s attention” appears, it is translated in French as attirer l’attention when the “someone” in question is hierarchically below the person drawing their attention, and by appeler l’attention (“appeler” being “to call”) when the “someone” is hierarchically above. The hold of hierarchy! Because we are translators, we see very well that in English the language of these reports is much closer to the vernacular than in French. This difference, probably more of a cultural nature than a technical one, raises questions, and principally the following one: to who are these reports addressed?

Given the energy invested in their translation, one is tempted to think that they don’t only serve to flatter some retrograde chauvinism in the countries that speak one of the six official languages. One would rather believe – reasonably, without sinking into a kind of demagogy – that these reports are addressed to everyone, and that their role is to inform people about problems that arise and about the solutions to them that can be found. That being the case, it seems to me that in French, as it already is in English, the language of the UN should be brought closer to that which is practiced by people.

That does not place in question the work of the translators, who are professionals recruited on standards of excellence after passing exams and who, for the most part, wish only for that, but rather that idée de la France, a misplaced Atticism that dunks the language in starch and leaves it as stiff as the shirt of a notable. If one otherwise accepted to dispense with it, or at least to simplify these usages, people would better understand what purpose the machin serves, because it does indeed serve a purpose. The thousands of meetings, the tens of thousands of working hours, every month, have a concrete, enduring and positive result on the world that surrounds us, and to translate for the UN is above all to take part in an active way in this process. Which, as an aim, is no small ambition.

-------------------------

Santiago Artozqui is a regular contributor to the online literary review En attendant Nadeau and this article is published in partnership with Mediapart. The subject of translation is explored in a series of articles in a dedicated section of En attendant Nadeau, which can be found here.

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse