The French army was deployed in Afghanistan between 2001 and 2014, alongside an international coalition of armed forces that first entered the country to combat Taliban and al-Qaeda in the weeks following the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States.

During that time it employed about 800 Afghans to serve as interpreters, and who played a key and often dangerous role in its missions. They, like all Afghan civilians who served coalition forces, risked their personal safety and that of their families, and were exposed to revenge attacks and intimidation by the Taliban, and more recently by so-called Islamic State militants, as Western armies pulled out of the country.

France, like other countries (and notably Britain) previously engaged in the conflict, has accepted little subsequent responsibility for its former interpreters, and only a handful were allowed safe sanctuary on French soil. The many left behind in Afghanistan, considered as traitors by the Taliban, live in fear of their lives amid continuing insecurity in the country.

Shortly after the election as French president in May 2012 of socialist candidate François Hollande, he put in place his manifesto pledge of finalising the withdrawal of French troops from Afghanistan. But while the military began returning home, no provision had been made for Afghan nationals who had served with the French contingent, and notably the interpreters, some of whom had spent many years in the job.

Abdul (last name withheld), a father of three, was among those whose request to relocate with his wife and children to France was turned down, despite serving 12 years as an interpreter with the French army – which had written glowing testimony of his conduct. “Everyone knows us. We took part in official ceremonies. Our names, our faces have been seen,” Abdul, then aged 51, told Mediapart in an interview in May 2015, five months after the last French troops had left his country. “When I stopped work, I found a threatening letter in front of my door.” He said he hardly stepped out anymore, and that he regularly moves homes with his family to avoid being identified. “I am afraid for my children,” he added. “If I die, what will happen to them?”

Abdul had kept a careful record of numerous documents and photos relating to his work for the French armed forces, including letters from ranking officers and their character references.

In one letter written in 2005 by a French lieutenant-colonel in charge of a training programme with the Afghan army, Abdul was congratulated for being hard-working and ready at hand, and of being “of an affable and disinterested character”. In 2006, a colonel in charge of the French military’s joint training centre for intelligence activities wrote that Abdul “particularly merited being cited as an example” for his work. In 2008, the commander-in-chief of the French army’s training mission with the Afghan military, the ‘Epidote detachment’, wrote of Abdul’s “fine human and professional qualities”, adding that he was “a man with resources and heart”.

Abdul told Mediapart he could not understand why his request to resettle in France was turned down. “Nobody wants to explain to us why,” he said. “The military tell us they are not responsible, and we don’t have access to the [French] embassy. It’s a bit sad. Why did the French friends leave us in danger? I don’t find the answer.”

At the time of that interview, almost four years ago, a group of lawyers in France, moved by a press report about a demonstration in Kabul that March by former interpreters who had been refused entry to France, had just set up a group together, led by Paris lawyer Caroline Decroix, dedicated to help fight for the interpreters’ asylum requests.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

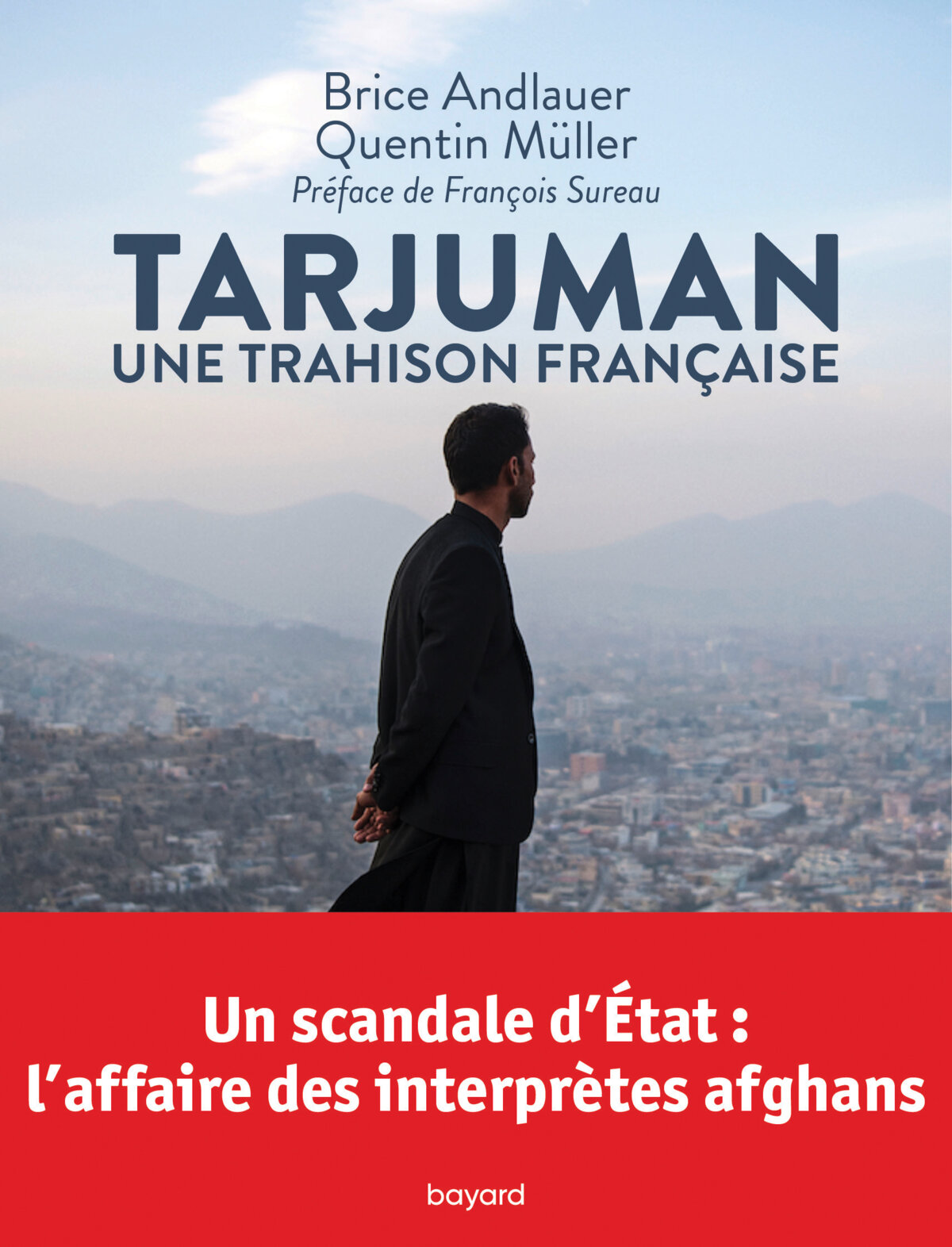

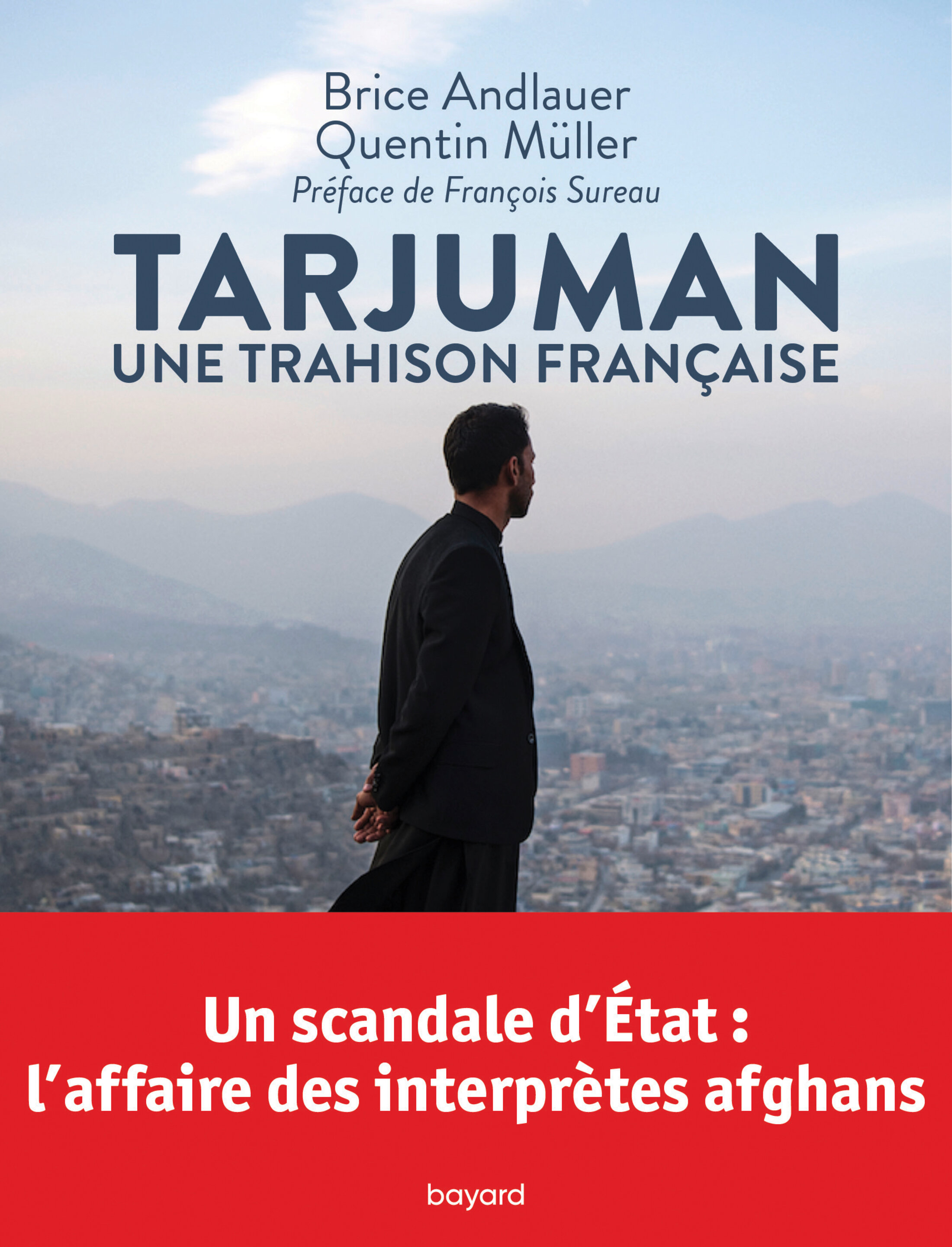

French journalists Brice Andlauer and Quentin Müller have followed Decroix on her trips between Paris and Kabul as part of a lengthy investigation into the history behind why and how the interpreters – called tarjuman in Afghanistan’s Dari language – have been snubbed by the French authorities. In their book Tarjuman, une trahison française (‘Tarjuman, a French betrayal’), published in France last month, Andlauer and Müller recount the long and desperate campaign of the interpreters in attempting to gain visas to enter France, applications which, when they were not clearly refused, were simply ignored. They detail the behind-the-scenes manoeuvring to deny entry to France for the interpreters and their families, the contradictory and sometimes cynical justifications given by the French authorities, and gathered first-hand accounts from a number of diplomats and military figures, some of whom describe their outrage at the betrayal, as well as from among political circles.

Mediapart publishes below the translation of a telling extract from the book, which details the opposing views within the French embassy in Kabul about the treatment of the interpreters, and quotes from correspondence by officials attempting to devise strategies to deal with the growing anger of those abandoned. Some explanatory notes are included by Mediapart, in hard brackets and in italics. It begins with the confidential notes sent to a colleague by a member of the French consular services in Kabul dealing with visa applications.

-------------------------

"As I told you, the PCRLs [the French administrative abbreviation for ‘locally recruited civilian personnel’] with who we spoke about a future meeting with the ambassador are languishing a little. I met two yesterday, who explained to me the illusions that were prompted by the invitation we made to them to put in a request for a visa. [Illusions felt] among themselves, but perhaps, above all, among those close to them, and their in-laws. For them, if we if we have led them to put in a request, it means that it will be delivered […] And they can’t prevent themselves from comparing their situation with numerous others who have left, and which they believe, in terms of [being in] danger, is no different. Which causes a strong feeling of failure, frustration, even resentment. One of them craftily spoke of his contacts with the press.”

A few months later, tensions rose to a new level, as the same French embassy official reported. “The refused applicants [for a visa to France] really have the impression that we’re playing them along by endlessly repeating this vague promise which they don’t really believe. I began handing back passports yesterday, which prompted comments, more than disenchanted, of ‘Well done France’. I was close to the point of calling security to throw out a former PCRL who was very upset and who wanted to share that with me, while I had other visitors in the visa section.”

Bertrand [a member of the consular staff interviewed at length by Andlauer and Müller] spoke of the inaction of the new ambassador, Jean-Michel Marlaud, who was appointed at the end of 2013, and how Paris insisted it had halted the repatriation procedure. The army, meanwhile, said it could no longer be involved because of the troop departures. The ambassador was eager not to “make waves”, keenly avoiding opposing himself to his hierarchy. The situation was beginning to rot. The war between the two ministries [defence and foreign affairs] was creating a monster: consented inaction. No-one was making a move and everyone hoped that the interpreters’ discontent would be stifled and short-lived. The dust was swept under the carpet.

During the two years of 2013 and 2014, the interpreters who had received no news flocked to the embassy to ask what was the state of their applications for visas to France. Bertrand wrote: “When one would ask ‘What’s the situation with my file?’ we would rummage through 25 boxes. They didn’t suspect anything, because when you’re in a position of power, you can always disguise things. So we told them, ‘Right, we’ll do some checks’.”

In fact, behind the armoured windows of the embassy, little by little, the boxes filled with passports and individual applications went missing. “One day, I remember, they found a box with 200 passports inside!” recalled Bertrand. During internal meetings, he alerted his hierarchy and the ambassador to the situation, warning that they could not keep all the passports, and the risk of losing them was too great. What could be done? The repatriation process was halted. “The interpreters didn’t come to get them themselves, because their visa request had not been [officially] turned down,” explained Bertrand. He came up with the idea of passing on the files to the last French contingent present on the ground, whose mission was to train the national Afghan army. “The army refused because it would have meant travelling left and right among the different bases across the country,” he said.

The hope among the interpreters was kept up by the combination of a lack of means, of organisation, of will, and the aim of nipping in the bud a discontent which had no yet spilled over. An email from the defence attaché, Patrick Sicé, dated March 29th 2013, detailed the new strategy adopted by the diplomats: “We spoke again yesterday of this business, in a service meeting with the ambassador. The pressure from former PCRLs and those who have filed applications is continuing, as much with regard to [the army] as upon our consulate. It appears to be time now to change our line and begin to get the message across that it’s over, and to have a more direct approach. Which is to say, that we take in applications but that we tell them that they have very, very, very [sic] little chance of obtaining a visa. We have provided protection to those who to whom we have felt it was necessary, there will be no more departures like those that have been carried out [except for one case mentioned by Sicé]. There needs to be a pause in the repatriations to France. The Force [French army] must put in place a framework of support for relocation within the country, which to my knowledge has not yet begun.”

To our knowledge, this framework of support, which is supposed to help some former PCRLs escape threats by moving to new homes in Afghanistan or in a neighbouring country, never existed. Above all, the email confirms the clear and firm intention of the authorities to halt all repatriation, contrary to what Bernard Bajolet [French ambassador to Afghanistan between February 2011 and April 2013] and [former commanding officer of French troops in Afghanistan, General] Olivier de Bavinchove both implied in interviews with us.

A little later, in January 2014, Patrick Sicé sent out another email detailing the procedure put in place to discourage the interpreters from visiting the embassy. “The procedure put in place last year, decided in agreement with the Force, allowed for the Force to inform those [visa] applicants who had not been chosen,” he wrote. “There are also certain application files which were blocked before reaching the embassy, which therefore the embassy did not know about […]. The aim being to protect, behind an administrative wall, our agent in permanent contact with all those who were disappointed.”

At the beginning of 2014, Abdul Raziq was the target of several anonymous phone calls threatening him directly. His complaints filed with the Directorate for Intelligence and Defence Security (the DRSD) prompted no reaction. He therefore made an appeal to all of his colleagues whose requests for protection had been dismissed, to bring them together for the first time. In February 2014, they gathered together at the Bagh-e Babur park [Garden of Babur] in Kabul where they unfurled their protest banners and marched towards the Green Zone to hold a demonstration in front of the French embassy. It was the first time such an event had occurred in Kabul.

“The ambassador sent out his guards with the military attaché,” recalled Abdul Raziq. “They made us disperse and when we asked why some [interpreters] had left for France while others were still waiting, they did not reply.”

Between 2014 and 2015 there were more protest demonstrations. From his ivory tower, Jean-Michel Marlaud [who had succeeded Bajolet as French ambassador] observed the events, sending out his personnel to the front line to calm the interpreters. Bertrand remembered that painful period. “The ambassador abandoned us,” he said. “He told us to drop it. He managed the affair in an extremely nasty manner. He laid low.” In reality, Marlaud hoped the protest movement would run out of steam. “For Marlaud, it was, ‘I’ll save my head from the chop’,” continued Bertrand. “It was, ‘Paris mustn’t take this badly, I don’t want to lose my post’. He never went to meet the demonstrators outside. He sent the poor defence attaché. He’d call him and say, ‘there are 20 to 25 guys demonstrating in front of the embassy, you’re going to go out and calm them’. The colonel did what he was told but he had nothing to say to them. What do you think he could have said?”

In face of the continuing demonstrations, Bertrand advised his colleagues that they should accept to meet with at least two spokespersons from the movement. “I said to one of them, ‘Get them to talk as much as possible, and listen to them. Transcribe their requests and make out a separate note where you write down your impressions. Afterwards, pass it on’.” According to Bertrand, the atmosphere inside the embassy was becoming difficult, and dialogue with Jean-Michel Marlaud came to an end. “I had staff who wanted to repatriate everyone, but it must be understood that it was impossible to discuss with Marlaud,” added Bertrand.

In the end, forced by the regular demonstrations, the ambassador accepted to open the embassy doors to two interpreters who were supposed to represent their colleagues. One of them was Adib Khodadad. It was the beginning of 2015, and the relocation procedure remained halted. The battle of the interpreters against the French authorities had just begun., Passing the visa processing section inside the fortress that was the French embassy, Adib had no idea that the requests for visas, that were so important for them, were lying untouched in boxes. Stepping inside the ambassador’s office, there was an exchange of cold handshakes. Jean-Michel Marlaud began by pretending that he had not responded to the interpreters because of the “jump” in immigration in France (it was the period when the so-called “migrant crisis” in Europe had begun). “I reminded him that we were not migrants, but people who had served France and that we were soldiers,” said Adib Khodadad. The French ambassador indicated his agreement, impassive. He told the two interpreters that he would transmit their comments to Paris. “He was indifferent and didn’t want to help,” recalled Adib. We asked Bertrand whether the ambassador lied to the interpreters? “It’s not me who said so,” he answered.

-------------------------

Tarjuman, une trahison française is published in France by Bayard, priced 18.9 euros.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse