Shaj Mohan and Divya Dwivedi are from among a new generation of Indian philosophers, and are the co-authors of Gandhi and Philosophy: On Theological Anti-Politics, a study of the concepts of Mahatma Gandhi (published by Bloomsbury).

Mohan is a regular contributor to Indian academic journal The Economic and Political Weekly. Dwivedi is an assistant professor teaching philosophy and literature at the Indian Institute of Technology in Delhi, and she is guest editor of the forthcoming edition of UNESCO’s Women Philosophers’ Journal, entitled Women, Philosophers, Intellectuals in India: An Endangered Species?

In this interview together with Mediapart’s Joseph Confavreux, they offer their analysis of the history of Hindu nationalism in India, represented by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, the BJP, the role of so-called ‘post-colonial’ thinking in the BJP’s project, and the role of he who they describe as “the father of post-colonial theory”, Mahatma Gandhi.

-------------------------

Mediapart: The current government in India appears to base itself around the valorisation, pushed to extremes, of Hinduism and its traditions.

Shaj Mohan: The history of the Hindu fascist movement in India is older than that of independent India. But it is younger than the idea of British India. The most powerful rightwing Hindu organisation ever, and the most powerful organisation after the state in India is the RSS, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, which can be translated as national self-service corps. It was formed in 1925.

Today, the Indian state propaganda and many Indian academics would say that Hinduism is the most ancient religion in the world. In fact, it is one of the most recent religions in the world. It is the most recently invented ancient religion in the world. This word, Hindu, didn’t exist as a religious category before the 19th century. The history of the word Hindu reveals to us the process of Hindu nationalism.

Divya Dwivedi: The Hindu religion was invented as a response to certain progressive legal measures introduced by the British Raj. In 1850, the British colonial administration brought a law called “Caste Disability Removal Act”. This law made it a crime to discriminate against people on the basis of caste for the first time in the subcontinent. Until the appearance of this law caste discrimination was the normal or the way of nature. This new law alarmed the upper caste population who, at that time, wouldn’t call themselves Hindu at all; instead they would call themselves Brahman, Kshatriya and so on, which are like the Genus concept of caste.

In 1871, the British Government initiated a pan-India census process. They found that when questions were asked like “what is your religion?”, people would say “Brahman”. And when asked “what is your caste?” the answer would be again “Brahman”. The word Hindu doesn’t appear to them to be the answer to these questions.

But when the combinations of the figures of populations came through, it was shocking that the upper caste population was a small minority. The findings of the censuses from 1871 to 1911 led the British administration to initiating another step, because now they had a practical problem. They couldn’t have hundreds of religious names and caste names. They needed a smaller number of categories in which all these people could be fitted together. So, they proposed the name Hindu for these hundreds of caste groups. Hindu was to be understood as a religious grouping that is separate from Islam, Christianity, Buddhism, and Sikhism. Nobody knew what it meant to be in this new religion, except that if you went to the church on Sundays you were less likely to be a Hindu.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

S.M: When this name Hindu appeared as a category, many in the upper-caste groups found it really shocking because it is not an Indian word. It is actually an Arab word, derived from “Al-Hind”. The upper castes felt that it had an “untouchable” ring, “mlecha sabda”, to it.

But there was anxiety amongst the upper-caste population that if the census proves that they were a minority in the country, they will be in serious trouble. So they attempted to bring the lower castes also into this newly created Hindu religion. For the first time, the lower castes were given permission to visit certain temples, celebrate certain festivals. These concessions were themselves the effect of a census circular issued by the colonial administration which was trying to figure out who was Hindu and who was not. It asked the people questions like “are you allowed to visit the temple?” and “do you have access to Brahman priests for ceremonies in your families?”. So the upper castes initiated temple entries and other processes to merely fit the lower castes into the criteria set by the colonial administration for the term Hindu. The discriminatory caste-ist practices were left intact.

Mahatma Gandhi played a very important role in the creation of this religion, especially regarding temple entry movements. However, in those days Gandhi was opposed to intermarriage between the lower castes and the upper castes, and even to their eating a meal together. He would modify this position later due to the political challenges created by Dalit political leaders, especially Ambedkar.

The upper castes governed this religion, which was necessitated by the statistics. Keeping in mind the requirements of the British administration for this religion, they decided its gods, texts, and the degrees of participation each caste would have in the activities of this new religion. In fact, this power invested with the upper castes to decide the degree of participation of each individual in the society according to the caste order has not changed since ancient times. The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, the BJP, which is the electoral organ of the RSS, is only the continuation of this history, of the determination by the upper castes of what India and Indians should be. Today the governance of this society is done by a caste group called Baniya, or the trader caste, and then the Brahmans.

There is this word “govern” that Foucault was very interested in. It is related to cybernetics. It comes from the ancient Greek word kubernao, which meant to steer a ship. So you can see the relation it has to governance; those who govern steer the social ship. There is a related old Sanskrit term called Kubera. Kubera is the mythic god of wealth. We know that wealth truly steers. So the Kubera group of businessmen and traders together steer India in the Hindu direction now.

Mediapart: Earlier you mentioned that the academics follow the state project of “Hindu” as the identity of Indian caste groups. Do the academic programmes have a role in the success of the BJP?

D.D: In fact, since the 1980s, through an academic programme named “post-colonial theory”, the relation between the State and society has also been transforming effectively. If we look at the ancient societies of the subcontinent, they have the form of a king being obedient to the social Law. The state is absent. This fact has been established by legendary historian of the ancient subcontinent, Romila Thapar. The greatest king is the one most obedient to the social code, which is essentially the caste order. The king god Rama is the exemplar of this obedient king. The form and the permissible variations of the social order were decided by Brahmans.

In the modern state of post-independent India, there was this crisis with the appearance of a constitution of the European type. India is a secular, socialist, democratic republic according to the constitution, but the reality of the society is something else altogether, which is ordered along caste lines. The caste that people are born into still decides their jobs and possibilities in life. For example, if you are a Dalit you cannot ride a horse in most parts of India, nor can you marry a non-Dalit.

Post-colonial theory emerged into the political scene in the late 1980’s as a solution to this conflict between modern institutions and the caste order. Some important events of that time became occasions to establish the post-colonialist perspective by justifying misogynist traditions and calling feminism and secularism “euro-centric”.

For example, in 1987 a young educated girl named Roop Kanwar was burnt alive on the funeral pyre of her dead husband, following the traditional practice called “Sati”, or widow burning. Traditionally a woman is regarded as pure only if her sexual activity and reproductive function are strictly held inside the marital relationship. If her husband dies before her, the only way for her to remain pure is to die soon after him. Of course, it is ritualistic murder. This was a practice that was prominent in many parts of India, especially in north-west India. The British colonial administration had brought in legislation to ban this practice, and this legislation raised a number of debates about the role of British administration in reshaping the culture and practices in India.

In 1987 the attack on the feminists who protested this ritualistic killing was led by a sociologist called Ashis Nandy. Nandy gave theoretical formulations to oppose the modern views of the feminists: that the feminists were themselves the products of western ideology and epistemology, that they were trying to look at Indian society in the modernist terms that were forged by the colonial administration, and that they were inimical to the cultural identity of the subcontinent. These arguments are in fact a paraphrase of Gandhi’s opposition to the annihilation of the caste system.

Mediapart: What are the origins of post-colonial theory? How did it achieve this political success?

S.M.: It is important to note that there is something called a post-colonial condition. It refers to a society which has modern institutions including the constitution, the courts and the universities existing side by side with a social order which is very much opposed to it. It implies much more. For example, one does not speak a “mother tongue”. I do not know the language in which I dream, it could be any one of the four languages that I can speak. Languages appear in thought like lines on water in this unhomely state. Being unhomely in language is an excellent condition for imagination. But post-colonial theory is not an adequate theory for this post-colonial condition.

D.D.: We have to be careful with post-colonial studies whose primary methodology consists in the pre-emptive use of a technical term, “nuance”. Nuance is the attentive and careful reading of the texts of post-colonial studies, a kind of applied deconstruction, although not rigorously Derridean, in the following way: it holds colonisation to be a Eurocentric, epistemic violence which both instigates the construction of an ‘authentic’ non-Eurocentric episteme and justifies its valorisation. We can see that this explanation of an authentic Indian – Hindu – culture is both championed by the post-colonialist critique of Eurocentrism, and is superficially disavowed when the Hindu violence becomes internationally embarrassing. This disavowal is a “nuance” that can be held up as proof that post-colonialism is different from Hindu fascism. But the basic Hindutva insistence on anti-Eurocentrism has the approval of post-colonialists.

S.M.: “Nuance” is actually the cue for interpretation, the stress on meanings, and the persuasion to adopt a certain political direction. This is a very traditional Brahmanical practice, “nuance”, which you can get from your religious gurus or today from post-colonial theorists. In fact, it follows the traditional Brahmanical way of interpreting texts where one of the most important conditions for a correct interpretation is to see if you have authority, either as a guru or an authority conferred by a guru. Depending on who gives you the nuances, the history you write changes.

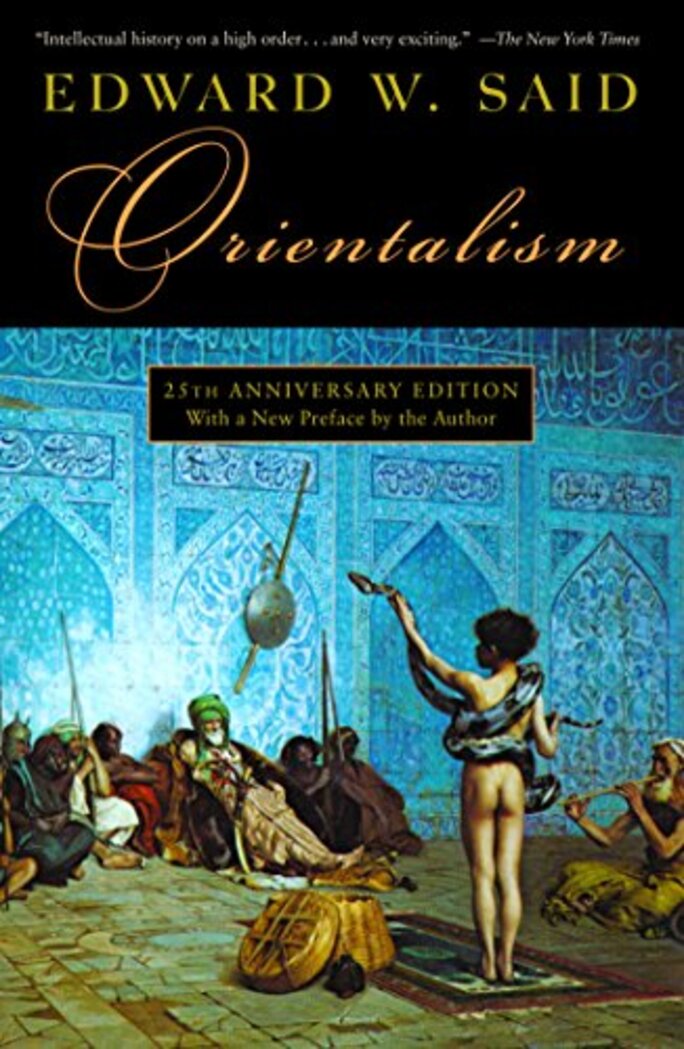

It is amusing that post-colonial theory derives its authority from the critique of what is called “European thought” by philosophers based in Europe. So, post-colonial theory begins with the authority of Europe as guru. One of its origins is in Michel Foucault’s researches. Edward Said wrote the influential book Orientalism, inspired by a misunderstanding of Foucault, and that work provided an awareness to all post-colonial societies about how they see themselves – the histories, the societies, the canon – through European lenses. They felt that they were condemned to this fate. Of course, this problem of seeing oneself through the lens of “the West” is possible only for the elites of these societies. Because only the elites have access to the European canon. The lower castes, for instance, reject the post-colonialist lens of the upper caste elite.

D.D: The other line is a school of historiography called “subaltern studies” which was trying to revise the nationalist way of writing history in India. One of the figures who led this historians’ movement is Ranajit Guha, who was based in London. Guha had some prominent students, such as Partha Chatterjee and Shahid Amin. These historians looked into the

Enlargement : Illustration 4

history of the independence struggle. Instead of focusing on leadership figures like Gandhi or [independent India's first prime minister Jawaharlal] Nehru, who were British-educated, they started to look at the villages which were not affected by colonial reforms. They found that there was a disconnection between the state-oriented programmes of the Congress Party, which was leading the independence struggle, and the common people living in the villages. The villagers were fascinated by people like Gandhi without knowing what he stood for. Subaltern studies is mostly a recovery and the celebration of the caste order which resists the state.

S.M.: Gandhi is an interesting figure here because he is the father of post-colonial theory. Many of the arguments of post-colonialist figures like Edward W. Saïd or Ashis Nandy can be found with Gandhi. Post-colonial theory is a “nuanced” and bawdy Gandhi.

Mediapart: How is post-colonial theory, and also Hindu nationalism, related to Gandhi?

D.D.: Shahid Amin is a great historian of the subaltern school – and also a kind of exception within it since he is the only one to address non-Hindu spheres –, which functions within post-colonial theory. He has a most intimate relation with the archives. He found an interesting fact: Gandhi was both a fakir and a sophisticated lawyer, and the latter disliked the attention the former received from the villagers. When Gandhi returned to India from South Africa, he discarded the attire of a western lawyer and started styling himself as an Indian peasant. From the peasant clothes he would change into fakir clothes; a fakir wears only his loin cloth.

S.M.: We feel that Gandhi should be understood as an unconscious “burlesque” in two senses: as a ribald political satire and as a striptease which takes decades to complete. The striptease of this burlesque figure seduced the villagers of India and the world. In order to create these effects Gandhi was deploying two languages at the same time. When he wrote for English newspapers or talked to the British administration, he would speak the language of modern law, because he was capable of that as a lawyer. On the other hand, if he had to write for the villagers or for the lower castes, he spoke the language of Hindu spirituality. Gandhi extended this equivocal speech to everything, even truth. Earlier we mentioned the conflict between the law according to the constitution and the law of the caste order. Gandhi mixed these senses of the law all the time. In this, too, he is a precursor of post-colonial theory.

D.D.: The villagers began to see Gandhi as a spiritual leader, or a guru, who was going to guide them to a spiritual victory, or even bless them with magical powers like a godman. Gandhi used the word “Swaraj” for independence, which means self-rule, or home rule. Sometimes, Gandhi spoke of a parliamentary form of self-rule. But at other times, he would say village rule, which meant preserving the traditional “Hindu” ways of life in India. This equivocal use of language between Western institutional theory and Indian spirituality contains the seeds of both post-colonial theory and the Hindu nationalist movement.

Mediapart: In what way are post-colonialism and Hindu nationalism different – if they are different?

D.D.: Post-colonial theory, Hindu nationalism, and Gandhi’s own project sought to recover the pure non-contaminated past of India. In this project, the degrees and qualities of the ambition differ between all the three. The expectation was and is that the past of India, the fictionalised idea of “the great Indian civilization”, would perform the very same role that Ancient Greece and Rome performed for the construction of Europe. So it is an imitation which tries to argue that “if it is great it happened in India first”.

Hindu nationalism and post-colonial theory both desire the same thing, but the only distinction – which didn’t last for very long – was that post-colonial theory wanted to rediscover the India which was just before European colonization or what we can call modernisation. Hindu nationalism instead had an older chronology in mind – they wanted to rediscover the India before the mogul rule began.

Nowadays there is no real distinction between the two. In fact, Hindu nationalism guides post-colonial theory. We have post-colonial theories that are moving towards a Sanskrit-isation of India, a Hindu-isation of India. One of the post-colonialist academics recently wrote an article in an Indian newspaper saying that the Indian constitution should reflect the Dharma of Indian society.

Mediapart: What is the meaning of Dharma?

S.M.: Originally it meant “to keep things together in a form” or “to fix an order”. It is also related to the Greek “Themis”, which too referred to order as something received from outside. In the ancient usage Dharma referred to the cosmic order. Later, it came to refer to the regular forms of society. It describes, as well as codifies, the regular forms of society. The texts which are collectively called Dharma Shastras, which means a system of codification of Dharma, list the social codes, their permissible variations, and the punishments for the violations of the codes.

Mediapart: Is this process of post-colonial theory and Hindu nationalism taking place in all institutions of education? Or, does that happen in specific universities or academic places? And how are they related to philosophy?

S.M.: Definitely, in all the universities and academic worlds where the humanities and social sciences are concerned in India. And now, increasingly in many academies in the European, American and Australian academic worlds. They see philosophy itself as Eurocentric.

Now, we must quickly define philosophy. Philosophy is the act of creating freedom; it takes place through the invention of new conceptual movements and also the creation of systems which give the concepts extra degrees of freedoms and range. In that sense, philosophy has no centrism. It should be possible to create philosophy anew everywhere with a simple question, “What do you think?”. The opposite of philosophy asks, “What did they think?”. This “they” could be the so-called original Aryans, proto Greeks, the inventors of religion and so on.

So, philosophy is a serious threat to Hindu nationalism, which is based on a certain “they” who were never in existence. It is a kind of common place to say that “philosophy is dangerous”. But in India being a philosopher can get you killed. Since 2013 three rationalist philosophers were shot dead in India.

D.D.: If we look at the practitioners or the proponents of post-colonial theory and Hindu nationalism, they have something in common. Post-colonialism is identified with the university and the academic world, and Hindu nationalism is identified with cultural and political fronts of the RSS, such as the BJP. But these two currents are led by the upper castes. The distinction, which is now disappearing, is that post-colonialists often had a kind of class superiority due to their Western education, cultural capital, and “the nuances” which allowed them to travel easily between the Western academies and Indian class rooms.

These two groups, which are really one, are themselves products of the institutions in the wake of British colonisation. But now they are speaking an equivocal language which denies this modern education to the lower castes and the poor, all the while using all the accoutrements of modern education.

So, post-colonial theory is used in order to deny modern education to the lower castes and classes, who are taught in regional languages and the quality of education remains extremely poor. It is funny to listen to post-colonialists from Gandhi onwards arguing in English that education should be in native languages and should concern native matters.

S.M.: The upper caste middle-class have control over the public sphere and the production of knowledge. Most importantly, they control the theories that provide the framework for production of knowledge, the directions of research, and the conduct of pedagogy.

This dominance of the upper castes using theory in this manner is also very ancient. This is what is called “Brahmanism”. It is the upper castes dominating the lower castes by using and controlling the theoretical language. Post-colonial theory is really the continuation of the ancient ways in this sense.

Mediapart: What is the effect of this kind of decolonisation? Is there a feeling of success in some degree?

D.D.: It is complicated, success might be failure in many ways. When Indians write about themselves, first of all they are expected to acknowledge the fact that they are contaminated by the Western and Eurocentric categories. This obligatory gesture installs a deconstructive notion of history which says “you will always return to the colonial moment to define yourself”. That produces something like a “double bind”, framed by the works of Jacques Derrida – which have Gregory Bateson’s idea behind it. There is a great deal of flexibility to such a theory. That this theory itself is itself happily European in its style and content is not a problem for its users.

Double bind is used to show that there is a trace of the colonial framework on whatever knowledge that can be produced in India. And that this very trace is also the trace of the violation of all other possibilities the Indian subcontinent would have organically had if it had not been interrupted by the colonial moment. So, although there appears to be a democratic impulse in post-colonial historiography, and particularly in subaltern historiography, the consequence of insisting on this failure – the double bind – is that we will always be confessing that every emancipatory discourse is a colonial discourse. And therefore, we will remain suspicious of any attempts that are made in the name of rights, in the name of equality, in the name of democracy.

So, decolonisation is not seen as a simple divorce between the coloniser and the colonised in social developments, in economy, in weaponology, and in trade relations. It is not a clean cut. Their argument is that once you are colonised, at a political and economic level, you can’t think outside the new framework that had been imposed by the coloniser. In other words, all of us are once and for ever colonised. This is how the “perpetual victim” is created. Hindu nationalists too see themselves as victims with respect to colonisation and also the Muslim minority.

Mediapart: What more would you say about how post-colonial theory works in the social and political spaces?

S.M.: First, theory in politics is the creation and defence of a terrain. In this sense, theory implies battle lines, which requires at least two parties. There has never been a theoretical warfare or a class warfare in India because there has been only one theory and then its variants. Theoretical polemic as something through which the lower castes could assert their position is yet to happen. Because theory, the institutions for theory, and the theorised public sphere are controlled by the upper castes belonging to post-colonialism and Hindu nationalism. Theoretical discourse is used, with the support of the Western academics and intellectuals, to suppress a real theoretical confrontation in politics.

D.D.: Now Indian society and its future are theoretically determined by post-colonial theory, which is an everyday language one can hear in television news studios. Post-colonial theory together with Hindu nationalism decides the directions Indian society can take, it alone speaks for Indian Society, and it decides which language should be used by who. Can, for instance, a non-Indian speak critically about Indian society? That becomes difficult.

Further, if an Indian speaks critically of Indian society and uses the language of rights, she becomes an illegitimate speaker. When Dalits, formerly "untouchable people”, demand that caste be recognised as racism so that they get international legal protection, they are said to be ignorant of Eurocentrism.

S.M.: It is very important to note is that post-colonial theory coincides with and supports the rise of the Hindu Right in India. The Rama Temple movement developed at the same moment as post-colonial theory became prominent. The temple movement was initiated by the RSS and one of the leaders was L. K. Advani, who became a deputy prime minister in 2002. He claimed that the fictional king god named Rama was born exactly on the location where a 15th-century mosque was standing. He said that unless this mosque was demolished and a temple was built for the fairy tale god Rama, the Hindu people will lack self-dignity.

This was also the time when a new kind of caste reform, based on the Mandal commission report, was to be tabled in Parliament. This reform allowed for a greater degree of reservation for Other Backward Classes – OBC, a collective term used by the government of India to classify castes which are socially and educationally disadvantaged. This created a strong resentment amongst the upper castes. BJP’s first phase of electoral victory in history was on the surge of this temple movement and the anti-lower caste movement.

The second phase began in 2002 with the pogroms in the state of Gujarat, when Modi was the head of that state, which killed more than 1,500 Muslims. This created the second wave of political prominence for Hindu nationalism, which was based entirely on the hostility towards Muslims. Since Modi, the term Hindu came to be primarily defined as Islamophobia.

Mediapart: What has happened since 2002 in the academic and intellectual spheres?

D.D.: Around this time, the early 2000s, Post-colonial theorists started to refer more and more to the Sanskrit texts of the Vedic period and fairy tales of the king god Rama and other minor gods. Seminars began to be conducted regularly on such themes. Delhi university’s English literature department held at least two seminars in the last two years on this very caste-ist, or racist, religious text called The Gita. So, a Hindu-isation of academic disciplines is now underway. Today most of the feminists, sociologists, political theorists and intellectuals accept “the Hindu direction” with some variations. And now this language called “Hindi” is being imposed even more aggressively on speakers of numerous other languages in the subcontinent.

Mediapart: What would you say about Hindi?

D.D.: Hindi language is an invention of the 1940s, it came soon after the recently invented Hindu religion became established. Hindi was invented to distinguish the Hindu language from what was considered an Islamic language, often called “Hindustani” or “Urdu”. Hindi adopted a new script and imported Sanskrit words and pronunciations in order to distinguish the so-called Hindus from the speakers of Urdu. Urdu originated centuries ago in the market places during the Mughal rule without any state programmes. It became the language of high culture, and was even the language of Bollywood until recently. But over the past several decades, Urdu has been identified as a purely Islamic language.

S.M.: India has a huge diversity of languages and cultures. The implications of the development of Urdu and Hindi are nationwide. Indian nationalism was European in the sense that nationalism didn’t exist in India, nor did the idea of a nation state. But the independence movement created this desire to be a nation like other nations, and to have a national language in which all citizens could communicate.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

It was necessary for inventing a community and for the conduct of codified politics. Which could be the language of this new nation which had so many languages within it? There were several local languages that were spoken in the north-west of India, which had varying degrees of similarities towards each other but also noteworthy differences. Alongside the independence movement, a language had to be invented which somehow could be attributed to a large part of the population. Hindi was built for that purpose, in order to absorb and at the same time annihilate the other languages by demoting them to the status of dialects of Hindi.

Mediapart: How did Hindi become Hindu?

D.D.: How was Hindi given a Hindu characteristic? Sanskrit was used for that, under the assumption that it was a language that originated in India just like the ‘Aryan’ people who sprouted in India, which is false of course. Words of Persian and Arabic origin and their cognates were programmatically weeded out, and their usage is actively discouraged. Hindi is a Sanskrit-ised version of the Urdu language.

Mediapart: What are the consequences of this obsession with origins, home, the outsider, and spontaneously created language?

S.M.: After forcibly establishing the Indian origin of the ‘Aryan’ people, Hindu caste order, and Sanskrit language, the Hindu nationalists could argue that since Muslims came to India during the medieval times, Islam is a foreign religion. Hindu nationalists do not grant other religions a reality. They say that other religions are superficial; superficially Muslim, superficially Christian, superficially Sikh. They say that everyone in India is really truly Hindu. Using this argument, violent reconversion programmes have been initiated recently to bring people back to their true home, which is the Hindu caste order. It is called “Ghar Vapsi”, or “Return home”.

The opposite of the original and the homely is the outsider. Violence is defined by Gandhi as the force which comes from the outside. The figure of the malicious outsider is in fact operative in post-colonial theory and Hindu nationalism.

The lowest castes are termed as outsiders or outcastes. Those who are outside the caste order, whose touch is impure, and in some cases even their sight! The distinction between the outsiders and the natives, which can only be characterized in terms of the caste system, is fundamental to the idea of Hindu and of Hindu nationalism. For example, a white European would be called either “Mlecha” or “Sudra”, which are terms referring to the lower castes. Whereas Sanskrit, which is actually derived from a people who came to the subcontinent many centuries ago, is regarded as the native language. That is why modern Hindi was Sanskrit-ised and declared the official language of India.

D.D.: A very important part of the political scenario today is that many people of the so-called lower castes, especially the Dalits – which means the people who are oppressed or broken – do not consider the colonial rule to be the most decisive moment. For them, there has been no relief in the oppressions by upper castes ever. The oppression of Dalits is the invariant in the history of the subcontinent. In fact there is even a positive appraisal of the colonial period from Dalit and lower-caste scholars. This tension between the so-called lower castes and the anticolonial upper caste elite began with the debates between Gandhi and Ambedkar.

-------------------------

- An abridged version of this interview translated into French can be found here.