Is CETA already dead? That was the question resonating through Europe this week as European Union officials frantically sought to get the EU-Canadian trade deal – formally known as the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement – back on track.

It was dealt a crippling blow last week when political leaders in Wallonia – a French-speaking region of Belgium with a population of 3.5 million – said they were unable to back the free trade deal in its current form. This meant that Belgium itself was unable to sign the agreement, which requires the backing of all 28 EU member states. As a result Canadian officials announced late on Wednesday that prime minister Justin Trudeau would not be flying to Brussels this Thursday, October 27th, for a planned signing ceremony.

On Thursday news came through that the Walloons and the Belgian national governement had finally reached an agreement even though the deal was too late to stop Thursday's summit being postponed. The Canadians have insisted all along they are still prepared to sign the agreement “when Europe is ready” and the deal was eventually signed on Sunday October 30th. But despite the last-ditch agreement the delay in signing the CETA deal has caused disarray at the European Commission, which put its full authority behind the negotiations.

The stance taken by the Walloons and also the Brussels region towards CETA had attracted considerable criticism. In the Flemish area of Belgium, where there is strong support for the deal, critics have shown particular irritation. They have attacked what they see as the political manoeuvrings of a socialist government influenced by trade unions and the Belgian labour party the Parti du Travail de Belgique (PTB) in a region they consider lives solely on state subsidies. The Walloons retort that they have been acting in line with the framework of new federal laws that the Flemish imposed on them in the name of regionalism.

At the same time Wallonia's stance was met with applause and encouragement from opponents of the CETA free trade deal. They have congratulated the courage and tenacity of the Walloon government which, they say, has been the only body to stand up to the European Commission on the issue. These opponents hope that the Walloon objections means an end to this kind of agreement, which they say hands power to multinationals against nation states or, at the very least, will lead to renegotiations of them based on a different approach.

The Walloon government itself has denied suggestions it wanted to destroy CETA, saying it simply wants to improve the trade deal, not finish it off. “It is even more important to fix lofty social, environmental and commercial rules given that this agreement is seen as serving as a model for all the others,” the socialist head of the Walloons government Paul Magnette said last week. The other key agreement on everyone's mind is the planned EU-United States agreement known as the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) sometimes also known as the Trans-Atlantic Free Trade Agreement (TAFTA). Given the high stakes involved, said Magnette, all negotiations need to be carried out with full transparency, in a democratic framework and with the consent of the people. His comments contained a style and high-mindedness that, say many critics, one would be hard pushed to find in France. The initial rejection of the agreement had been down to Wallonia's “democratic vitality”, Magnette said.

The Walloon political leaders therefore insist that they do not want to be depicted as stuck-in-the mud locals fighting against the modern world but simply as people “defending their convictions”. Paul Magnette has also been adamant that his region will not be bullied into agreeing to the accord. “We will not decide anything under an ultimatum or under pressure. Every time you try to put an ultimatum it makes a calm debate and a democratic debate impossible,” Magnette said on Monday.

The president of the Walloon Parliament, centrist André Antoine, has also warned against outside pressure to hurry them. “There's a huge mish-mash of texts. I have 300 pages of texts, 1,300 pages of annexes, two or three interpretative declarations.... ultimatums and threats are not part of democracy. We want a deal, we want a treaty, but we want to negotiate it with a minimum of courtesy and respect,” he declared.

The Walloons have been worried about several aspects of the proposed CETA deal and, they say, demanded substantial modifications. The first concern is over planned measures for arbitration courts which they say risk leading to the creation of a parallel non-state justice system that will allow multinationals to take action against nation states over measures or rules that they consider are against their own interests. They were also alarmed at the absence in the free-trade agreement of clauses offering reciprocal safeguards over agriculture and key local produce brands, a gap that they fear American companies could exploit. They have also raised questions over the maintenance of public services and public safety policies. All this, they say, shows the need for tighter measures.

Yet none of these concerns were new. For ever since September 2015, when the European Commission first unveiled to political leaders the results of its seven years of negotiations with Canada, the Wallonia region has said that it had a problem with the text of the agreement and that it would refuse to sign it in its current state, as it is entitled to do under Belgian federal law. However, at the beginning this warning was greeted with general indifference.

It was only in the summer of 2016 that the national Belgian government started to wonder what the French-speaking Walloon region really wanted. And it was only in the last few weeks, after the signature for the EU-Canada deal was set for Thursday October 27th, that the Belgian government and European leaders realised that the Walloons were not joking and that they were not going to ratify an agreement they did not like. Suddenly everyone began to panic.

In less than a month officials did all they could to make up for lost time. The European Commission set a number of deadlines that came and went: first the Walloon government had to give its agreement by last Thursday, October 20th, then by Friday, then Sunday and then Monday. All through this process, which has continued on through the rest of this week too, European officials and leaders have been seeking to get the Walloon government to yield, employing a carrot and stick approach, to ensure the official signing could still take place this Thursday October 27th. Though an agreement was finally reached on Thursday, it was not in time for the planned summit.

Loss of legitimacy

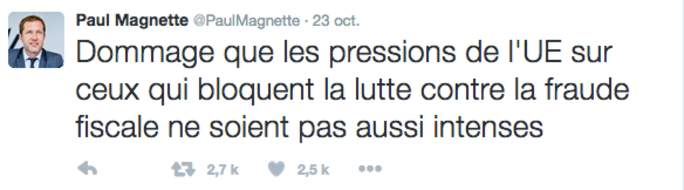

The pressure exerted by the EU machinery had certainly not been appreciated by the Walloon region. In particular local leaders took exception to some of the comments from the president of the European Council, Donald Tusk. “Too bad that the EU's pressure on those who block the fight against tax fraud is not so intense,” Paul Magnotte Tweeted angrily (see below).

The European Commission has since denied that it has been applying pressure to the Belgian region. “The Commission traditionally does not set deadlines or ultimatums,” said EU Commission spokesman Margaritis Schinas. Indeed, officials insisted it was showing “patience” towards Belgium's problems. In truth the Commission had little option, unless it wanted to provoke a constitutional crisis in the country.

Coming after the Greek debt crisis and the Brexit vote, the reluctance of Wallonia to sign the CETA deal has certainly caused further damage to the structure of the European Union and its international reputation. At the start of October, as doubts began to mount about the signature deadline, Canada singled out the Commission for criticism, claiming it was no longer able to negotiate on behalf of everyone in the EU. Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau said : “...if Europe cannot manage to sign this agreement, then that sends a very clear message not just to Europe, but to the whole world, that Europe is choosing a path that is not productive for its citizens or the world. And that would be a shame.”

Since last week the attacks have grown even more ferocious. The president of the Socialist Group in the European Parliament, Gianni Pittella, said: “It is obvious that if a small community is able to hold 500 million EU citizens hostage – whether one agrees with the specific reasons or not – there is a clear problem with the decision-making process and the implementing system in Europe.” He added: “Either the fundamental functioning is changed or the EU risks being sentenced to irrelevance.” Writing in The Wall Street Journalcommentator Simon Nixon wryly noted: “Perhaps the European Union’s problem is too much democracy rather than too little.”

Backers of the CETA deal place the blame for the obstacles first and foremost on Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker. Though under the Treaty of Rome the Commission has always had compete freedom to negotiate commercial agreements on behalf of everyone, Juncker agreed that the deals currently being discussed should be subject to approval by parliaments - and not just by state governments. Critics say this has opened the door to all kinds of last-minute bargaining and populism. “If we leave community policy in the hands of politicians of all kinds, it's a problem,” says Sébastien Jean, director of the French international research institute the Centre d'Études Prospectives et d'Informations Internationales (CEPII).

British observers are perhaps the most nervous about the hold-up to CETA, given the context of the Brexit vote. They fear that if the EU is unable to get all states to sign a deal with Canada that is judged relatively inoffensive, what will happen when Britain starts speaking to the other EU states about its own future trade relationship with the bloc?

In fact, observers point out that it was the very loss of the Commission's own legitimacy in this area that made it necessary to refer the deal to national parliaments for approval. “Given the animosity towards the EU in general and trade deals in particular, the decision to allow country by country ratification of CETA, rather than asserting the EU’s right to set policy on external trade, was a pragmatic one,” said the Financial Times. If the Commission is at fault, say other observers, it lies in not having taken sufficient account of Europeans' doubts and criticisms, in not having sought to build a broad consensus around some issues and in not having worked with full transparency.

The mistrust shown by Europe's citizens towards trade deals can be better understood when one appreciates how much people feel they have lost in terms of democracy, social rights and the environment faced with the power of money. “The opposition to trade deals is no longer solely about income losses.... It's about fairness, loss of control, and elites' loss of credibility. It hurts the cause of trade to pretend otherwise,” writes Dani Rodrik, an economics professor at Harvard Kennedy School.

Moreover, people's reluctance and uncertainty about these trade deals have grown because they go much further than simply reducing trade tariffs, which are already down to virtually zero. Instead these agreements seek to bring in new norms, shake up rights, cultures, attack modes of production and consummation, and impose rights to multinationals in relation to nation states.

“Lots of people are hiding behind Wallonia,” says Paul Magnette accusingly. In fact, CETA and other free trade agreements are already facing growing opposition across Europe. In Germany, Austria, Holland, France and all over the continent there are more and more protests, and two weeks ago more than 300,000 people took to the streets in Berlin to show their disapproval of them.

The problem is that only the regional parliaments in Belgium have been authorised to confront this deal before it is signed. Other parliaments only have the right to consider the accord once it is concluded, and then have to decide whether to approve or reject it in its entirety.

However, while much has been made of Wallonia's opposition to CETA, a verdict on the agreement handed down by Germany's constitutional court has been greeted with near total silence. Yet, potentially, it is just as significant as the Walloon refusal to sign. On October 13th the Federal Constitutional Court in Karlsruhe ruled that while the German government could ratify the agreement with Canada, there were conditions. These are that Germany must be able to leave the agreement at any time if it asks; and that Berlin cannot accept the measure on arbitration courts. According to the German court, the working of these bodies runs counter to the German constitution, as they raise the risk of a parallel justice system operating against the German state. In other words, it is not just non-governmental organisations and a handful of the usual suspects who are against this anti-democratic measure.

Meanwhile, as is its custom, France has procrastinated. On the one hand the French government has insisted that the Canadian deal – CETA – is the best possible accord. “It's a good, exemplary, agreement, which is nothing like the one in which the European Union is embroiled with the United States, and it must be rapidly implemented,” prime minister Manuel Valls said recently. On the other hand, the junior minister for overseas trade Matthias Fekl has insisted that France is opposed to the TTIP and that negotiations should be stopped. As for President François Hollande himself, he has on several occasions sought to persuade the Walloon leader Paul Magnette to accept the CETA deal.

Yet the difference between CETA and the proposed TTIP is miniscule, especially as the Canadian deal could serve as a Trojan horse for all American multinationals. Rather than equivocating or hiding behind tiny Wallonia, many in France would have preferred the government in Paris to have led the debate on CETA with the same conviction and seriousness as the Walloons have done. That would have been to the benefit of all parties, including Europe itself.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter