Senior management at the French banking giant Société Générale validated the payment of vast secret commissions via tax havens as part of an operation to corrupt Libyan officials in order to gain lucrative contracts in the country, documents obtained by Mediapart suggest.

The corruption operation, for which the bank, as a legal entity, has officially accepted its responsibility, was active between 2005 and 2009 during the regime of the late Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi, who was killed in 2011.

In separate legal proceedings in the UK, the US and France, it has been established that during that period the banking group secretly paid an intermediary with close links to the dictatorship more than 90 million euros, via his Panama-registered company, to further its investment ambitions in Libya. A total of 14 investments the bank gained through bribery have been identified, worth a total value of more than 2 billion dollars.

The intermediary was identified as Libyan businessman Walid Giahmi, who controlled the Panamanian company Leinada Inc.

The Société Générale, commonly abbreviated to “SocGen” outside of France, has already settled three legal proceedings, in 2017 and 2018, over the corruption scam. The first of these was in the UK in May 2017, when the bank agreed to pay 963 million euros to Libya’s sovereign wealth fund, the Libyan Investment Authority (LIA), in compensation for the deals obtained by bribery, shortly before the case was due to be heard by the High Court in London. The bank apologised to the LIA as part of the agreement whose terms otherwise remained confidential.

In June 2018, the SocGen settled similar criminal and civil cases brought against it in the US and France for the corruption of the Gaddafi regime officials, when it admitted guilt and agreed to pay 1.3 billion dollars.

To settle the legal action in the UK, US and France, the French bank paid a total of almost 1.5 billion euros, including 250 million euros to the French treasury under the deal agreed in 2018 with the French prosecution services’ financial crimes branch, the PNF. Despite that deal, the PNF is today continuing with investigations into eventual personal responsibilities in the case.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

It was as part of those investigations that Elyes Jebali, one of the principal whistleblowers behind the revelations of the SocGen corruption campaign, was questioned on December 13th by the French national police force’s anti-corruption, financial and fiscal crimes unit OCLCIFF (l’Office central de lutte contre la corruption et les infractions financières et fiscales).

Jebali, meanwhile, has launched proceedings against the bank before the Paris industrial tribunal for unfair dismissal. The SocGen fired Jebali citing his “gross misconduct” and his “lack of loyalty” over the revelations of the Libyan scam.

The documents now obtained by Mediapart, which are all classified as “confidential”, come from an internal inquiry which the SocGen commissioned international law firm Herbert Smith Freehills (HSF) in 2015, just after the initial suspicions of the bank’s implication in the Libyan corruption scandal emerged.

The bank’s management has for years publicly blamed some of its staff over the corrupt dealings in Libya. After the initial settlement with the Libyan sovereign wealth fund, the LIA, in London in 2017, the bank issued a statement in which it said, “Société Générale wishes to place on record its regret about the lack of caution of some of its employees". But the documents now obtained by Mediapart, which amount to around 70 pages mostly made up of interviews by HSF with key staff involved in the Libyan operations, and also internal email correspondence, illustrate a far more complex situation.

One of the tactics of the bank to avoid arousing suspicions over its corrupt dealings was to keep secret from contacts among Libyan officials who were not aware of the bribery the identity of its intermediary with close links to the Gaddafi clan. This involved the use of the financial structure in Panama through which the illicit payments transited.

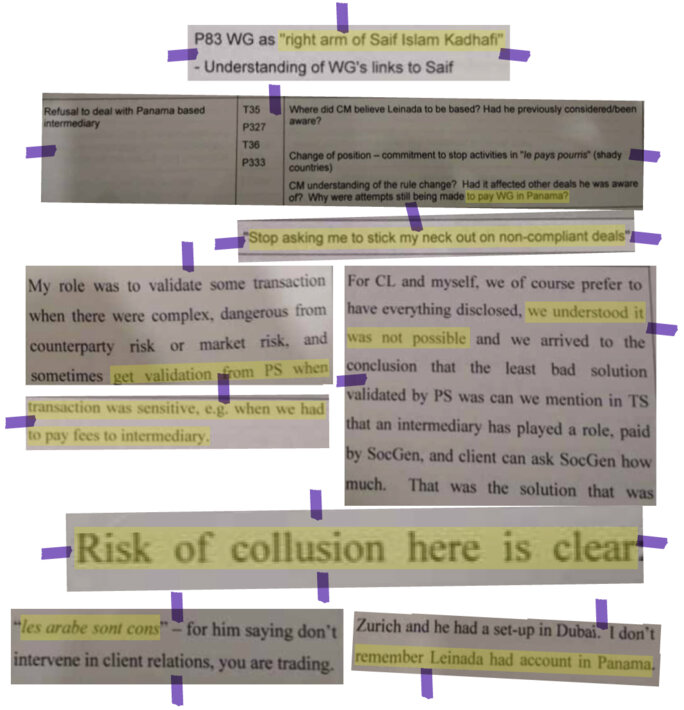

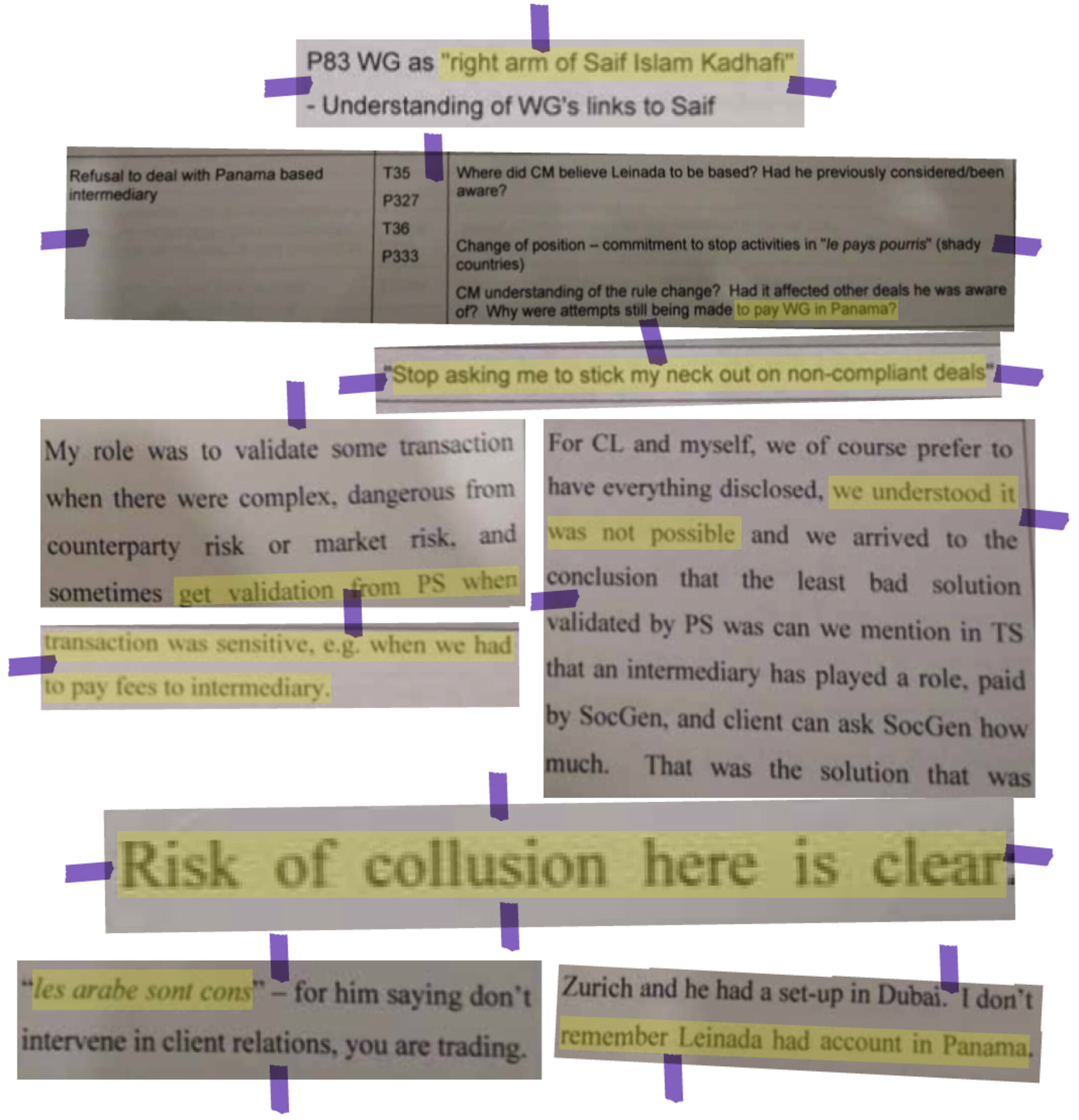

According to the documents seen by Mediapart, the dissimulation was decided at a very senior level at the bank, and in particular by Patrick Suet, its deputy general secretary and later, in 2009, general secretary, and currently secretary of the bank’s board of directors. His name features recurrently in the documents, most often under the initials “PS”.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The HSF inquiry questioned senior SocGen manager in charge of investments, Christophe M. (last name withheld), and also Christophe L. (last name withheld), in charge of the bank’s equity derivative department. Their textual replies are reproduced here in their original sometimes approximative English. Christophe M., in his reply dated June 15th 2015, said: “For CL and myself, we of course prefer to have everything disclosed. We understood it was not possible and we arrived to the conclusion that the least bad solution validated by PS was that we could mention in TS [editor’s note: “term sheet”, the name for a document outlining terms and conditions of a business agreement] that an intermediary has played a role, paid by SocGen, and client can ask SocGen how much. That was the solution that was accepted.”

Christophe M. added that this solution was accepted with regret because Libya’s Gaddafi regime was “an important client”.

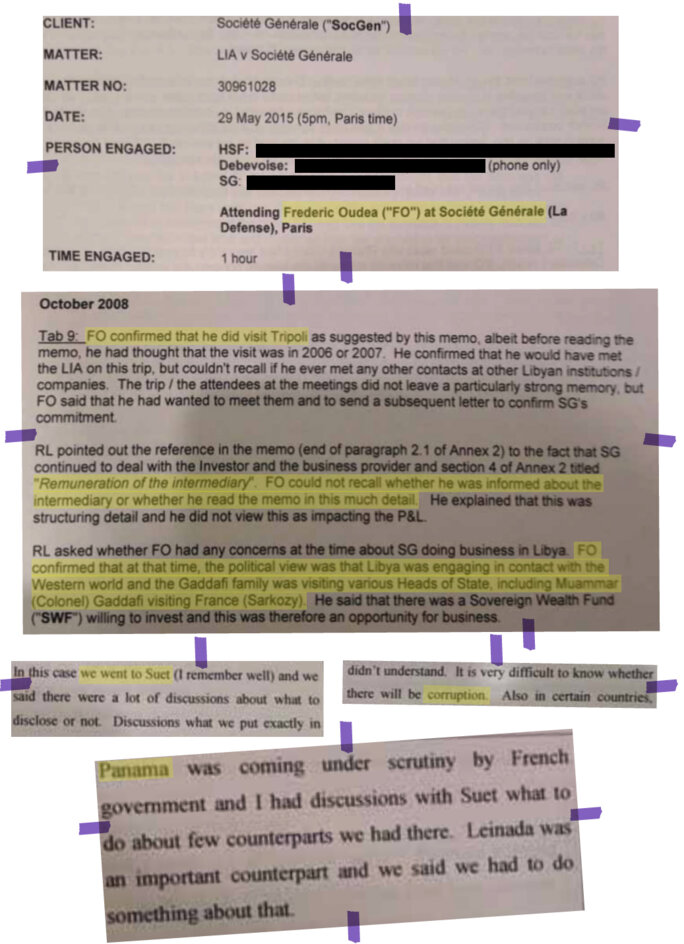

Christophe L. in a textual statement dated April 29th 2015, told the HSF team that he had had doubts about the adopted method which he said he found strange. He confirmed that “this type of deal” was managed “on high” because of the sums involved. “In this case we went to Suet (I remember well), and we said that there were a lot of discussions about what to disclose or not,” he recalled.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

The name of Patrick Suet was also cited by both men with regard to the vast secret commissions the bank agreed to pay, and which judicial investigations into the affair have conclusively identified as the source of funding for the bribery of Libyan officials. These were paid into the Panama-based company Leinada Inc., notably via a SocGen account in the Swiss city of Zurich. “My role was to validate some transaction[s], when there were complex, dangerous from counter party risk or market risk, and sometimes obtain validation from PS [Patrick Suet] when transaction was sensitive, e.g. when we had to pay fees to intermediary [sic],” Christophe M. told the HSF inquiry.

His colleague Christophe L. described the sums involved in the intermediary’s commissions as uncommon, adding that he and his colleagues gave the matter particular attention during the procedure. “It is very difficult to know if there will be corruption,” he said.

Christophe M. said they had been perhaps too naive, but at the time they did not think the intermediary had paid anyone, rather that he simply wanted “to be rich”. With hindsight, he said, the sums appear enormous.

Those questioned by the HSF inquiry presented differing recollections concerning the connection with Panama, a notorious tax haven where vast international money laundering activities were exposed in the 2016 Panama Papers leaks. Christophe M., said “I don’t remember Leinada had account in Panama [sic], while Christophe L. detailed: “Panama was coming under scrutiny by French government, and I had discussions with Suet [on] what to do about few counterparts we had there. Leinada was an important counterpart and we said we had to do something about that.”

Christophe L. added that he could not remember when France drew up a clear blacklist of internationally uncooperative tax havens, but that Suet had begun to be concerned about dealings with some countries, in particular Panama, before it became officially blacklisted – which he recalled happened in 2010.

But during the period between 2005 and 2009, which is the subject of the ongoing criminal investigations into personal responsibilities, there was apparently no obstacle for the SocGen’s operations with Libya. Some warnings were made within the bank over the secret payments transferred to Panama via Zurich, but to no avail. In several emails dated February and June 2008, one SocGen employee warned of “infractions of our own regulations” and called for “this high-risk account”, the object of which they could not understand, to be closed. In their report, the HSF legal team cited a document written by Christophe M. in which he demanded: “Stop asking me to stick my neck out on non-compliant deals.”

The links between the SocGen intermediary, Walid Giahmi, and the Gaddafi family were well known on high, although his competence in banking and financial matters was less established. In an internal SocGen document from June 2007 it was noted that the intermediary was above all known to be “right arm of Saif Islam Kadhafi [sic]”, a reference to Gaddafi’s second son, Saif al-Islam. In its closing report before the settlement reached with the bank in 2018, the French prosecution services’ financial crimes branch, the PNF, noted that, “This proximity was the basis of the contractual relationship that was established by the intermediary”.

SocGen chief executive Frédéric Oudéa is also called into question by the HSF documents seen by Mediapart. Oudéa, a former advisor to Nicolas Sarkozy when the latter was budget minister between 1993 and 1995, was questioned for an hour by the HSF inquiry at the bank’s headquarters at La Défense, on the outskirts of western Paris, on May 29th 2015.

Regarding the vast sums paid to the intermediary and which appeared notably excessive with regard to the services rendered, Oudéa said he had, “No problem” with the amount in question. Questioned about a trip he made to Tripoli in 2008 to sign a litigious deal worth 500 million euros, the HSF jurists, in the documents obtained by Mediapart, paraphrased his responses as follows: “He confirmed that he would have met the LIA [Libyan Investment Authority] on this trip, but couldn’t recall if he ever met any other contacts at other Libyan institutions/companies,” adding that for Oudéa, “The trip/the attendees at the meetings did not leave a particularly strong memory”.

Regarding a memo he was sent by email on October 9th 2008 in which the payment to an intermediary was noted, the jurists reported that “FO [Frédéric Oudéa] could not recall if he was informed about the intermediary or whether he read the memo in this much detail”.

Asked whether he had any concerns about SocGen doing business in Libya at that time, the HSF report said Oudéa “confirmed that at that time, the political view was that Libya was engaging in contact with the Western world and the Gaddafi family was visiting various Heads of State, including Muammar (Colonel) Gaddafi visiting France (Sarkozy)”.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Mediapart contacted the Société Générale about the comments that feature in the report of the HSF inquiry, and the information regarding the roles of Patrick Suet and Frédéric Oudéa in the Libyan corruption case. The bank sent the following response (in French, translated here): “Société Générale has concluded with the American Department of Justice an agreement for the suspension of prosecution, completed by a “guilty plea” agreement concluded by SG Acceptance NV (a subsidiary of the group). The bank has also concluded a judicial covenant of public interest with the [French] national financial [crime] prosecution services [the PNF]. These agreements follow in-depth investigations by the authorities. We invite you to consult these agreements, which have been made public, to determine the roles and responsibilities of each person in this case.”

“You will note that it is mentioned nowhere in these agreements that Mr Oudéa would have had knowledge of the failings that are identified in them,” the bank added.

Meanwhile, on December 17th, Bloomberg News, citing a well-informed but unnamed source, reported that the SocGen is searching for a successor to Oudéa, 56, who in May this year was reappointed as chief executive of the bank on a four-year contract. The report added that the successful candidate could be appointed before Oudéa sees out his current term.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The French version of this report can be found here.