On December 22nd, when the “gilets jaunes” movement in France was into its sixth successive Saturday of nationwide street protests, Arno Fortelny, a 35-year-old software developer in the United States, organised a “yellow vest” demonstration in front of the French consulate on New York’s Fifth Avenue, close to Central Park.

By that Saturday, the so-called yellow vests in France, whose movement began as a protest against a new eco-tax hike raising fuel costs – hence their use of hi-vis yellow jackets which all motorists must carry in their vehicles – had rapidly developed into a far wider and ongoing protest against falling living standards among low- and middle-income earners, and anger at the country’s social and political elite.

The ongoing protests have now entered into their 12th week.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

“Let the working people of this country finally unite outside our decrepit political establishment to come together against the common enemy: the ruling class and its politicians,” proclaimed the Facebook page set up for the New York event in late December by Fortelny, a militant with the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) party which has seen its membership numbers soar since the 2016 election of Donald Trump as 45th president of the US.

“Only *we the people* can end this failed neoliberal nightmare to bring freedom and prosperity to all,” added Fortelny on his Facebook post, calling on those planning to attend the demonstration to bring “signs, yellow vests and good vibes”.

On the day, only a handful of people showed up, outnumbered by NYPD officers on crowd-control duty. But in truth, Fortelny, a volunteer with the election campaign of Democrat Party leftwinger Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, elected to the House of Representatives last November, had not expected to spark a mass movement.

“I really just wanted to get people together, show solidarity with our brothers and sisters in France,” he told Mediapart. “I’m not expecting a big yellow vest movement here. It's fantastic how that came to be in France. It's a class protest and that makes it important, special. What has made it successful is that it's not Left or Right, it's a class struggle.”

“Everyone is frustrated, that's why we got Trump, Brexit, [French far-right leader, Marine] Le Pen,” added Fortelny.

Americans have followed the yellow vest campaign in France via the TV networks which have mostly covered with dramatic images of torched cars and commercial premises vandalised during demonstrations in central Paris.

Jamie Tyberg is an activist and director for development with the Brooklyn-based New York Communities for Change, an association that describes itself as leading a fight “against economic oppression” and social disadvantage in the city’s low- and middle-income neighbourhoods. She said she was not shocked by the sometimes violent images of the yellow vest movement in France.

“Speaking as an individual, I've always thought only organized violence could overcome the violence of the bourgeoisie, so in that sense I feel energized by this movement,” said Tyberg, who added that the original grievance that prompted the French protests – the new eco-tax on fuel – raised the question of how environmental policies are approached. “I absolutely agree that this has challenged mainstream environmental groups to realise that climate policies and actions will have to be socially just, and anti-capitalist in nature,” she argued. “But then again, indigenous communities and organisers in the global south have been saying that for years. It shouldn't take a bunch of young French people protesting for the ongoing demands of communities of colour to come to light.”

In an inward-looking country where its president, Donald Trump, monopolises the agenda of major cable networks from morning to night, the French yellow vest movement is nevertheless hardly at the centre of TV news coverage, in contrast to coverage in the press, which has regularly followed the movement – albeit without the same interpretation as Arno Fortelny or Jamie Tyberg.

For in the US, the view about the French yellow vests is inevitably clouded by Donald Trump, the self-declared hero of the American working class, a globalisation adversary and proud champion of nationalist policies, whose 35-day partial closure, or shutdown, of federal government activity was the first – and unsuccessful – step in his battle with the Democrats in Congress for the funding of a wall on the Mexican border to halt a supposed invasion of immigrants.

Just before the yellow vest movement erupted, Trump took to Twitter to attack French President Emmanuel Macron over his approval ratings in opinion polls. “The problem is that Emmanuel suffers from a very low Approval Rating in France, 26%, and an unemployment rate of almost 10%,” said Trump in a November 13th post. It began a spat that sealed a departure from the honeymoon period between the two leaders earlier last year, when Macron was feted by some in the US media as “the new leader of the free world”, and, in a supposedly amicable relationship of differences, “Trump’s ideological opposite”.

In December 2018, as the yellow vest protests multiplied into nationwide unrest, Trump continued with his barbs against Macron. "The Paris Agreement isn’t working out so well for Paris,” he wrote in a post on Twitter on December 8th. “Protests and riots all over France. People do not want to pay large sums of money, much to third world countries (that are questionably run), in order to maybe protect the environment." He added the false claim that protestors were chanting “We want Trump”, an example of “fake news”, subsequently debunked by news agency AFP.

Trump’s claims that, in sum, the yellow vest revolt is one against the introduction of policies to slow climate change, was relayed by a number of hard-right figures. One of them is Sebastian Gorka, who served as Trump’s national security aide in 2017, and who Democrats accuse of links to white supremacist groups, and who is a regular contributor to Fox News (see here his comments to the channel on the yellow vest movement) . Another is radio talk show host Rush Limbaugh, whose audience is chiefly in rural America.

Some Trump supporters have created “Yellow Vest” groups, which remain small, posting online messages of support, notably on Reddit discussion boards, for the French yellow vests, but also others that carry racist overtones and the promotion of conspiracy theories.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

In Canada, the largest “Yellow Vest” group online, with more than 100,000 members, was temporarily shut down earlier this month after there were threats posted against the country’s prime minister, Justin Trudeau. Protests by the Canadian so-called yellow vests have been marked by anti-immigration themes touted by the far-right.

Those within the large "liberal" centre of the US political spectrum have been following with caution, even concern, the development over the past two months of the yellow vest phenomena, a movement which they consider to be a “populist”, a term with negative connotations in the US and which, as historian Steven Hahn detailed in an article published this month in leftwing weekly The Nation is ill-defined. For them, the anti-tax and anti-elite messages, sometimes joined by conspiracy theories, they see in the movement is a disturbing aspect.

Neera Tanden is the head of US think tank Center for American Progress which has links to the Democrat Party. Close to Hillary Clinton, Tanden took to Twitter in early December to comment on the unfolding yellow vest movement in France. “I don’t understand why any progressive is cheering French protesters who are amassing against a carbon tax,” she wrote.

Her post drew a stinging reply from the Democratic Socialists of America party: “Because regressive taxes that don't make the rich and fossil fuel companies pay their fair share are, you know, bad? Because working class people don't want to foot the bill for crappy neoliberal policies, and we know when we're being screwed?”

That exchange is an illustration of the wide gap between the Democrat Party establishment, which is close to the world of large corporations, and the leftwing militants who denounce its relationship, including financial dependence, on big business. The leftists have called – so far without success – on the Democrats, who now make up the majority in the House of Representatives, to push for a programme to radically reduce over 15 years the carbon emissions of the country’s economy.

'Racial resentment and cultural anxiety got Trump elected'

In an article that largely sums up the concerns over the yellow vests as widely expressed in the media and among US "liberal" commentators, a Paris correspondent for The New Republic, a twice-monthly magazine centred on politics and the arts, slammed the movement for its racist elements and taste for conspiracy theories. In his article, headlined “The Ugly, Illiberal, Anti-Semitic Heart of the Yellow Vest Movement”, Alexander Hurst reports that “despite the legitimate economic pain and despair that have been highlighted by the protests, anti-Semitism, conspiracy theories, illiberal politics, and violent insurrectionism have been inextricable from the movement practically from its beginning”.

Hurst details racist, anti-Semitic and Islamophobic incidents and speech, and the sometimes wildly false rumours that have circulated, notably on social media, among some of the yellow vests, and “the illiberal streak, with members partially blocking the distribution of a major newspaper, Ouest-France, after it ran a critical editorial”.

He concludes, “how sad that, like the far right, a chunk of the left has become fascinated by the mob, choosing to pull bricks out of the wall in the hopes of climbing the rubble to political gain”.

But there was no detail of the demands of the movement, the political gains it has achieved, the solidarity it has inspired, the police violence that has left demonstrators seriously injured, or the attempts by some of the yellow vests to explore new democratic procedures like the experiment in north-east France for a novel citizens’ popular assembly.

Writing in the leftwing US bi-monthly, Current Affairs, journalist Vanessa A. Bee, a French citizen who travelled to France in December to visit her grandparents, offers a different analysis of the movement. She sets out the social and institutional demands of the yellow vests, beginning with their call for a “citizens’ initiative referendum” (which proposes a national referendum to decide upon an issue which has first attracted sufficient support in an online petition). Bee, who is black, (“I may be French, but my skin is black and my blood Cameroonian,” she writes), notes the prevalence of whites in the yellow vest demonstrations (but notes they are not exclusively white, and also include a large contingent of women), and expresses her concern at what she detects to be a “faint smell of nationalism and xenophobia”.

“Welcome to France,” she writes.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Beyond the agitation among those who make up the base of support for Trump – who takes care to maintain their fanaticism – the eruption of the yellow vests has also revived debate about the disillusionment and anger of the American middle class for which the US president made himself the self-styled hero of during his election campaign. Before his election, the issues were little aired, but have now become a regular feature of discussion and they most certainly will be at the centre of the next presidential elections in 2020.

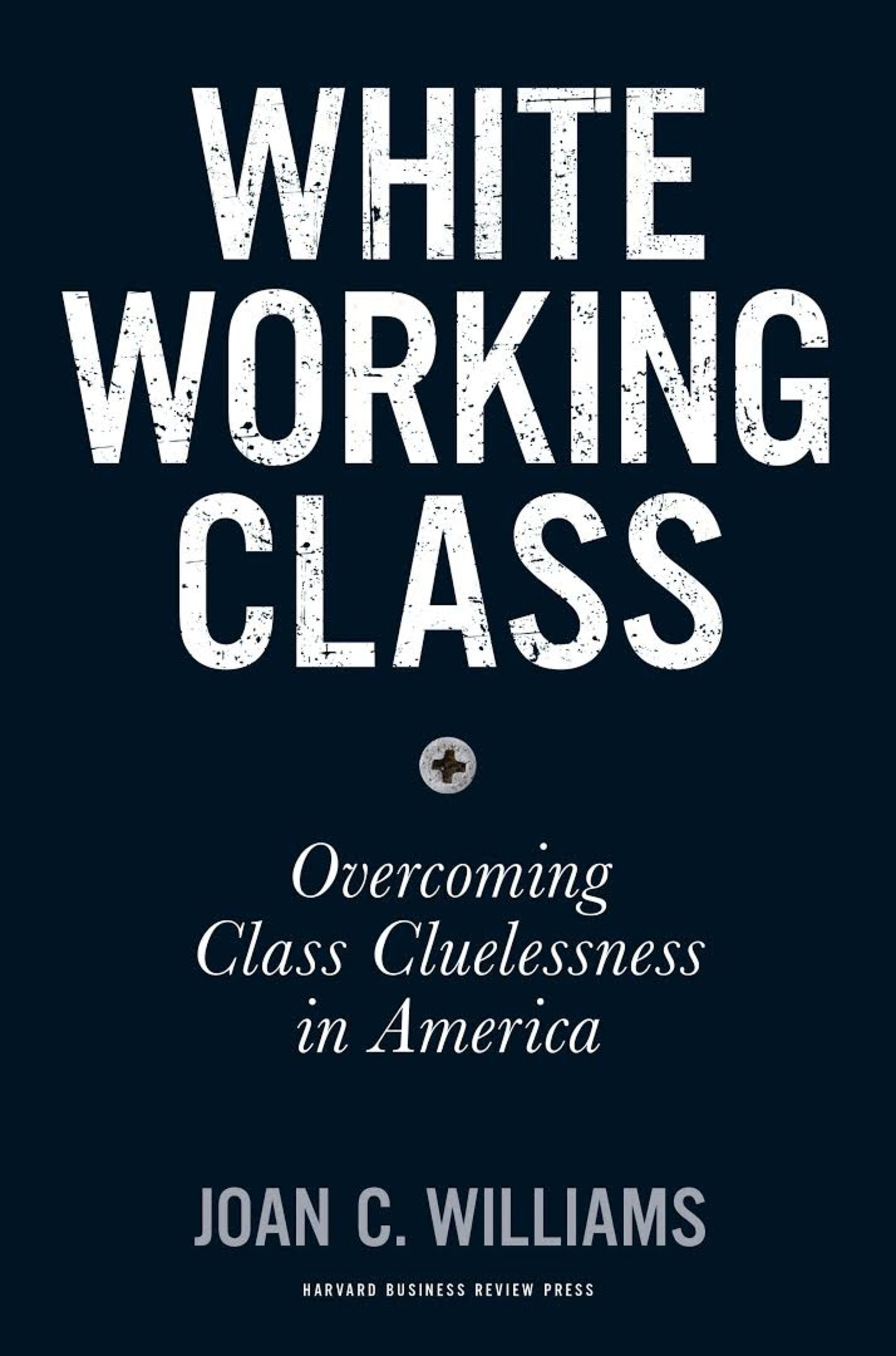

Joan C. Williams is a Distinguished Professor of Law at Hastings School of Law, at the University of California, and is a specialist in issues of gender inequality. She is also the author of White Working Class, a best-selling study in which she underlines how the social elite’s analyses of the white working classes is so often erroneous. She told Mediapart that she sees parallels between the yellow vest unrest and the frustrations of the white American middle class (although she notes cultural differences also).

Enlargement : Illustration 4

In White Working Class, which was published just after Donald Trump’s election, Williams examines the great divide between the American elite, a social minority but which dominate the cultural scene, and the true middle class, neither wealthy nor poor, often white and from rural environments, which has felt insulted or ignored amid their economic decline. She underlines also that this social group, which she identifies as having a yearly household income of 40,000-130,000 dollars, represents 53% of the US population.

Williams, who the Democrats consult with as they prepare to build a political platform capable of beating a Trump re-election bid in 2020, is an outspoken advocate for equal rights for Afro-Americans, for women and the LGBT population. She points out that the lower income groups among the black and hispanic population are also hard-hit by globalisation, de-industrialization, and who will be also further hit in the future with increasing automation of work. She is certain that beating Trump will depend upon forming a coalition that includes many different social groups of all racial kinds.

But she underlines the situation of the white lower middle class, and notably male blue-collar workers, who until the 1970s were presented as a social model but who have since then lost their economic and social status, alienated by snobbism of the classes above. With a falling standard of living, and lack of consideration (and the subject of derision, such as with the stereotyped Homer Simpson character in the series The Simpsons), Williams says there is “no mystery why they are absolutely furious”.

“They’re sick of being condescended to, sick of having more traditional cultural values depicted as ignorance, sexism or xenophobia,” she argues. Williams says the aspiration is to have a job that allows the attaining of a middle-class standard of living, and that Trump was the first politician in a long while to promise them that.

From what she argues, it would appear that the popularity of some of Trump’s racist overtones is less to do with any deep-seated racism among the white middle class but more about the lack of debate that highlights the class issue. Williams says that the people who feel abused use the language available to them, and that often in the US that relates to race.

But that idea, which highlights a form of historic and cultural humiliation that sometimes results in racism, is contested or relativized by others. For Donald Trump, who uses the codes, either explicitly or implicitly, of white supremacists, has indeed revived what Carol Anderson, professor of African American Studies at Emory University, calls “white rage” in her 2016 book White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide, a divide she dates back to the early years of modern American history.

Anderson argues that Trump hit the bull’s eye in his targeted conservative electorate who for decades were fed on a sentiment of resentment towards black people. “Not even a full month after Dylann Roof gunned down nine African Americans at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina,” she writes, “Republican presidential front-runner Donald Trump fired up his ‘silent majority’ audience of thousands in July 2015 with a macabre promise: ‘Don’t worry, we’ll take our country back’.”

In an article for the US online news outlet The Intercept, published last November just ahead of the US mid-term elections, Mehdi Hasan underlines that several studies carried out among Trump supporters (notably by political scientists John Sides and Diana Mutz), reveal that “racial resentment and cultural anxiety” among a certain white electorate – rather than economic fears – fuelled their vote for Trump. “Two years ago, in 2016, angry, white, working-class voters in the key swing states of Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin pulled the lever for Trump as a way of expressing their anger over economic injustice — and a populist blue-collar wave swept the billionaire property mogul into office,” Hasan wrote. “But a range of studies published since then from political scientists, economists, and pollsters have found that it was racial resentment and cultural anxiety – not economic anxiety – on the part of white voters that got Donald Trump into the Oval Office.”

'In France, uniting ‘the people’ against elites is possible'

It is no doubt the predominance of the notion of race in social issues in the US that explains the alarmed reactions of some American commentators, who see in the yellow vests in France a version of the politics peddled by Steve Bannon, the hard-right Breitbart News media executive who in 2017 served as Trump’s chief White House strategist and senior advisor. It also sometimes prevents them from understanding the complex nature of the French movement.

In a report published in The New York Times on December 5th, the daily’s Paris correspondent Adam Nossiter enlightened that appraisal, underscoring the difference between the yellow vest protests and populist movements in the United States and elsewhere in Europe. “[…] what makes France’s revolt different is that it has not followed the usual populist playbook,” he wrote. “It is not tethered to a political party, let alone to a right-wing one. It is not focusing on race or migration, and those issues do not appear on the Yellow Vests’ list of complaints. It is not led by a single fire-breathing leader. Nationalism is not on the agenda.”

“The uprising is instead mostly organic, spontaneous and self-determined. It is mostly about economic class. It is about the inability to pay the bills. In that regard, it is more Occupy than Orban,” he wrote, referring to the 2011 “Occupy Wall Street” movement in the US against financial inequalities and the power and privilege of finance, and which followed that year’s “Arab Spring” revolts and the “Indignados” movement in Spain.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

The socialist US quarterly magazine Jacobin has carried several articles about the yellow vests in France, inviting contributions from French far-left activist Olivier Besancenot, of the Nouveau Parti Anticapitaliste (New Anti-Capitalist Party), from French economist Cédric Durand, an academic and member of the leftwing Economistes Atterés association, Aurélie Dianara, a French research associate in economic history at Glasgow University and feminist activist, and also the Canadian-US actress and activist for numerous causes (notably for animal rights) Pamela Anderson, who has now settled in France. She has written several times in support of the French yellow vests, including a text, “Revolt! Don't React” published on her foundation’s website. In that piece, the former Baywatch star, who refers to “A revolt of the periphery” – “From the election of Trump as president, to Brexit, Catalonia, the Yellow Vests” – calls for a “manifesto for the revolutionary future”.

“We must fight against those who not only hold but hang on to power and wealth with relentless tenacity,” she writes. “We must stand against neoliberalism and its global and regional institutions. We must offer an alternative democratic and socially-just society, one devoid of social democratic compromises (especially those with big business).” She concludes: “The future will be either revolutionary or reactionary.”

Kevin Zeese is a lawyer and political activist, based in Baltimore, who helped organise the Occupy movement in Washington DC. He has published several articles about the French yellow vests on Popular Resistance, a website which reports on activist events and movements in the US. For Zeese, the two months of rolling yellow vest protests in France have helped put the “injustice” of neoliberal policies on the public agenda.

“The yellow vests are raising many of the same issues as Occupy, the 1% [most wealthy], inequality, corruption,” said Zeese. “All that was raised by Occupy. The tactic is different. Occupy camp out in the public space. The tactic of the yellow vests is successive week-end protests and crossing political barriers, just being a workers’ movement, a class movement, not Left and Right, across political ideologies.”

In an article published earlier this month in the leftwing quarterly review Dissent, Jacob Hamburger, a writer and co-editor of the French-American blog Tocqueville 21, and who is an experienced observer of French affairs, argued: “What the gilets jaunes have revealed is that there is in France today a large constituency of people who feel disconnected from politics: people who, by spending a Saturday occupying a roundabout with their neighbors, are literally seeking out new spaces for political action.”

“The gilets jaunes movement has shown that at least in France, it is possible to conceive of a coalition uniting ‘the people’ against ‘the elites’. At the same time, France’s actually existing left-populist party, Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s La France insoumise, has had a difficult time channeling the protesters’ anger into a viable political force. With the danger of the far right constantly in the background, the populist left will have its work cut out for it if it can ever hope to defeat Macron, let alone the neoliberal order he has come to symbolize.”

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.