The rightwards shift of France politically has become a commonplace idea, to the extent that former president Nicolas Sarkozy felt confident in telling the conservative newspaper Le Figaro at the end of August that “France is rightwing, probably more than it has ever been.” This diagnosis was also convenient, as it supported Emmanuel Macron's decision not to give the Left a chance to form a government after the parliamentary elections in July. And this view of a right-leaning country seems to have been confirmed by the changes that have taken place in France's electoral landscape since the end of François Hollande's presidency in 2017.

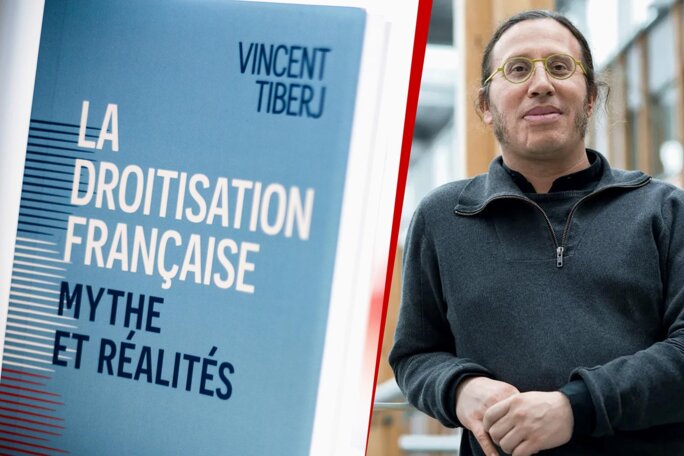

Yet for years political scientist Vincent Tiberj has challenged this accepted wisdom. With a certain degree of courage - given the unprecedented electoral gains made by the far-right Rassemblement National (RN) - he continues to argue his case in his recently-published book 'La Droitisation française. Mythe et réalités' ('France's move rightwards. Myths and realities' published by PUF). The phenomenon of a rightwards drift, he claims, certainly exists “in media discourse and in political life”. But he argues that it is out of kilter with - or even in contradiction to - broader movements within society itself, a society which cannot simply be reduced to its ruling elites or even to those who turn out and vote.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The author provides a wealth of information and in many respects presents a compelling argument, but there are blind spots in it which suggest that the debate needs to continue. There is also an unintended risk that overly “reassuring” interpretations could be drawn from Vincent Tiberj's work, which cannot just be boiled down to the idea that an electoral breakthrough is “within reach” for the Left. Indeed, in a nod to the song by Dougie MacLean, the academic from Sciences Po Bordeaux university in south-west France warns that we must be “ready for the storm…”

The challenge of how to measure public opinion

The book's first chapter is a mini-treatise on the proper use of opinion polls. Vincent Tiberj reminds us just how essential they are - or at least how they are the “least bad solution” - when it comes to understanding the attitudes that shape the population as a whole. However, he highlights their variable quality, depending on how the questions are formulated and managed. In other words, one-off polls conducted with 1,000 people that contain significant biases should not lead to hasty conclusions.

Tiberj himself has carefully constructed “longitudinal data” to track preferences that avoids these biases and aggregates the attitudes of the French public across three areas: socio-economic issues, cultural questions, and tolerance towards immigration and religious and ethno-racial minorities. When observed over a long period, specifically since the late 1970s, the evolution of these three indicators challenges the assumption of a general rightwards shift in society.

Public support for wealth redistribution may not be at its highest recorded levels, but neither is it at its lowest. As a result, there has been “no general conversion to economic liberalism”, he notes. On the other two fronts, there are even signs of a “leftwards shift” in public opinion. The rise in educational attainment and the advent of new generations have been significant drivers but so, too, in a less frequently discussed phenomenon, has been “reverse socialisation”, a process by which children influence the views of their parents and grandparents.

How, then, can we understand the electoral landscape of 2024 and the number of votes cast for the far-right Rassemblement National (RN)? Either the measuring instruments are flawed, or we need to seek explanations elsewhere. Vincent Tiberj believes that his indicators “remain particularly solid” and that “to my knowledge, there's no better way of measuring shifts in public opinion”. Even those researchers least convinced by his thesis do not radically challenge his tracking data. Instead, they point out that certain shifts in opinion are overlooked or too diluted in the combined indicators that he uses.

Political scientist Luc Rouban, who is about to release 'Les Ressorts cachés du vote RN' ('The hidden motives of the RN vote', to be published by Presses de Sciences Po), maintains that public opinion has hardened in recent years over the issue of cracking down on crime, with a “demand for tougher penalties”. Lack of recognition at work and social contempt are, according to him, another “vote-producing machine for [Marine] Le Pen”. This was also the argument made by political scientist Bruno Palier in Mediapart's columns last year, when he warned of the electoral consequences of pushing through the pension reforms.

Finally, while Luc Rouban acknowledges that the issue of balancing the budget does not inspire the masses, he insists that “entrepreneurial liberalism” - which values autonomy - has reached “very high levels, especially among the young”.

More broadly, one could argue that the fading of alternatives to capitalism, which remained vivid in people’s minds until the 1970s, is not fully captured in opinion polls. And the Left needs a strong and forward-looking project to mobilise people, as historian and former head of the French Communist Party Roger Martelli puts it, as well as “elements of social identification and hope”, which are sorely lacking, and not just in the context of France.

The answers to a paradox

Vincent Tiberj, in any case, offers a range of explanations for the disconnect between public opinion, as he measures it in society, and the results at the ballot box. He identifies political leaders and powerful media outlets in particular as the agents of a “top-down rightwards shift” in voting.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Indeed, there is a whole series of filters that exist between public opinion on one side and electoral behaviour on the other. Voting behaviour also depends on what is being discussed and how it is framed, given that many people are ambivalent in their views. This is either because their expectations themselves are contradictory, or because they are torn between opposing inclinations, making it difficult to predict which will prevail.

Thus the “framing” of certain events becomes crucial, for instance how we view urban riots may depend on whether they are linked to police violence and segregation on the ground, or to parental failings and the harmful impact of too much screen-time on young people. Similarly, what is put on the public agenda also matters; for example, when the public debate focuses on immigration and law and order, the RN is “playing on home turf”, and is sometimes helped in this by its supposed opponents.

In this regard, Vincent Tiberj explains, the rise of very right-leaning broadcast media, as well as social networks that limit exposure to dissenting information, are likely to “trigger a spiral of ideological reinforcement”. He writes: “If the rightwards shift seems to have spread, it's because there's indeed an intellectual and media echo chamber that finds its audience, which, though large enough, is clearly a minority.”

The political scientist also highlights what he calls a widespread sense of “resignation” in society. This is reflected in an open refusal to vote and a collapse in party political sympathies. All political groups have been affected by this radical disillusionment, which is even more pronounced among younger generations. However, Tiberj points out that the Left has suffered in particular as a result of the presidency of socialist François Hollande from 2012 to 2017.

In short, the reasons why society's progressive tendencies “don't translate” into votes can be found in the shortcomings of what is on offer politically. Regarding non-voters, the academic suggests that those groups who might express these progressive tendencies at the ballot box are the ones most likely to abstain. “Culturally,” he writes, “the most open generations are also those where intermittent voting dominates. […] When it comes to socio-economic values, it's clearly the issue of wealth redistribution that suffers the most from these changes in voting [patterns].”

The Left must not delude itself

Beyond the nuances mentioned earlier regarding exactly what is being measured in public opinion, some other questions remain, and there are also concerns about how Tiberj's work will be received by the Left. A recent triumphalist online article by Manuel Bompard, national coordinator of the radical-left La France Insoumise (LFI), illustrates this; he insists that the key to future electoral victory indeed lies in the so-called “fourth bloc” of those who currently do not vote.

If we focus on the 2022-2024 electoral period, there were several successive nationwide elections in which voter turnout ranged from 47% to 74%. Yet the combined score of the leftwing parties has remained stuck at around 30% of votes cast. While it is always possible to 'do better', how high does participation need to climb before this electoral base expands? The author talks of a “divergence” between citizens and voters, but one wonders when these groups might start to coincide.

Vincent Tiberj also notes there is an “obvious lack” of figures who embody the Left. Yet while the overall image of the Left has been tarnished since the Hollande era, for several years the LFI founder Jean-Luc Mélenchon has positioned himself as its champion by breaking from the former president. And even Olivier Faure, the current first secretary of the Socialist Party to which Hollande still belongs, has largely repudiated the latter's legacy. Although it is not the primary focus of the book, one might have wished for this issue to be addressed more directly, if only to outline the criteria for what would constitute more effective representation.

Even if the leaders of the Left were to change, their successors would still face the same structural obstacles. These include the decline in trade unionism and the fragmentation of working life, to which the author dedicates several pages. While progressive tendencies may languish in latent form within society, the Left should not assume that simply having the correct electoral message will be enough to spur people holding such views into action and vote. Without mutual networks and respected local figures to relay it across diverse social spaces and geographical areas, any such message may fail to reach enough of its intended audience.

More fundamentally, one might ask whether the distinction between “top-down” and “bottom-up” rightwards shifts in society is entirely sustainable. When a portion of the electorate doesn't change its values but begins voting for the Rassemblement National, it is hard to claim that it hasn’t moved to the right or that this shift only manifests itself in voting behaviour - which is hardly an insignificant act. Certainly, “top-down” actors may have played a role in shaping this behaviour, but the same was true when this portion of the electorate used to vote dutifully for mainstream governing parties.

In the past, filters between public opinion and the ballot box often worked in reverse, to the detriment of the far-right, even when society was far more sexist, homophobic, xenophobic and racist. While we can be pleased that this happened, was this any more normal than today? The gap between measured social attitudes and votes cast at the ballot box should not necessarily be seen as an anomaly, but rather as the outcome of normal political struggle, where the only option is to impart enough energy and strategy to prevail.

In summary, Vincent Tiberj’s work is valuable in deconstructing lazy narratives about an apparent and inevitable rightwards shift in the country. But we must avoid falling into another trap, that of imagining there is a “leftwing” France out there that is simply waiting to be awakened in order to become an electoral reality.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter