A founder of the maverick Appalled Economists movement, prominent French economist André Orléan, specialised in finance and monetary policy, is a member of the French national scientific research centre, the CNRS. In this interview with Mediapart's Ludovic Lamant, he warns that European handling of the national debt crises is "heading straight into a wall" and decries the "total strategic inertia" of a "divided and powerless" Europe. He argues for a 1930s-style New Deal and against austerity measures under which "wage-earners pay the high revenues of financiers".

-------------------------

MEDIAPART: After Greece in the spring, it's now Ireland's turn to come under attack. How serious is this for the euro zone?

André Orléan: This new crisis was predictable. It's following the same logic [as the previous one] which consists of managing public debt by reassuring financial markets. But it's very difficult to reassure the markets, when all you have to offer are austerity plans. These are based on weak growth and weak growth is the worst thing possible for an indebted country.

MEDIAPART: Is there anything different from the Greek crisis?

A.O.: The market reaction is different. The markets reacted very positively to the Greek plan of May 10th, 2010. Today, that's no longer the case. Other countries, which until now were not at risk, such as Italy, also saw their interest rate rise. In fact, the financial press is rather alarmist. It was not reassured by the Irish plan either.

With the Irish case everybody is waiting for the next case to crop up while slowly realising that this is not the right strategy. This case-by-case response, once the contamination hits a new country, doesn't work. We are going to move from one country to the next and increase the amount of European bailouts with each aid package. This will create recession which in turn will lead to even greater public debt problems causing debt to rise in an unmanaged fashion, without a clear outlook.

Nobody understands anything anymore. How can one get out of the spiral of debt if it is always allowed to rise? European policies have reached their limits. It's like a bottomless pit: the markets will never be reassured. Policies must be changed.

'Europe is divided, therefore powerless'

MEDIAPART: What should be done?

Without a united Europe, not much. The current situation shows that a monetary zone as integrated as the euro zone cannot survive without a strong political power. Experience with international monetary systems is, in this regard, unambiguous. Their stability was assured when a nation showed that it was able to assume a leadership role. That nation would impose its currency, from which it drew advantages but it also acquired duties towards the other countries.

Whenever leadership is lacking, the period is unstable. That was the case in the period between the two world wars when the United States did not want to take over from England. What we had then was, the United States, a country with the dominant economy and which was the world's creditor, applying opportunist policies in line with its own private interests. We are sort of in the same situation today with Germany and the euro zone.

MEDIAPART: Germany is only looking out for itself?

Yes. It is too self-centred. It doesn't see that its trade surplus is possible only thanks to the deficits of other European countries - because the euro zone is more or less balanced if taken as a whole. It would therefore not be in Germany's interest for these countries to pull out of the euro. Thus we have Germany which is dominant from an economic stand point, but which is incapable of understanding the collective interests of Europe, which only aligns with the northern nations and which despises the countries of the south of the continent. This leads to a total absence of collective vision and consequently to a total strategic inertia.

MEDIAPART: But there is little chance that this will change in the short-term.

This type of situation will not be solved overnight. I am very pessimistic. I don't see how we can carry on with these types of differences in the euro zone. One only needs to look at the disparities in payroll costs. At the centre of the zone, there is a country that won't stimulate demand, that maintains a tight lid on wages and which is dependent on exports. Meanwhile, for the so-called peripheral countries there are only austerity measures on the horizon.

Europe facing off with the financial markets reminds me of the battle between the Horatii and the Curiatii.1 Because Europe is divided, it is powerless. Each time it's the same story: the markets face off with an isolated country that they can easily vanquish. First there was Greece, then there was Ireland. Each time, despite its huge resources, Europe is defeated. Its political divisions lead it into a dead-end. It doesn't know how to benefit from its global power.

Today, it is abundantly clear that monetary sovereignty and political sovereignty are closely linked. The existence of monetary union without the equivalent political sovereignty is untenable. It was thought that the markets alone would be able to produce common interests. This has been a resounding failure.

Today it is clear that creating common interests requires political integration. Political action is the foundation of all monetary unions - especially through budgetary transfers. But monetary policy and public debt policies also have a role to play. The United States illustrates how a country can use political sovereignty to loosen economic constraints. Lacking such a mechanism, monetary union in Europe is no more than a major constraint resulting in austerity measures.

-------------------------

1: Myth told by Livy about a war between Rome and their close kin of Alba Longa under the reign of Tullus Hostilius in the 5th century BC, in which triplets from Rome, the Horatii, were designated to do battle with triplets from Alba Longa, the Curiatii.

'Removing dependency upon markets is the central issue'

MEDIAPART: Has European monetary union reached breaking point?

A.O.: The current policy of negotiated, case-by-case bailouts, with conditions set by the markets, is heading straight into a wall. It will, eventually, be confronted by Germany's refusal to continue the bailouts. At some point, the German people will decide they can no longer pay.

Today, one has the impression that we are living in a remake of the 1930s, that is, a series of deflationist schemes that are pushing the European economy further into crisis. In 2008-2009 it was possible to think that European countries, by implementing plans to stimulate the economy, had taken on board the lessons of Keynes. But today the only policies mentioned are budget tightening, lower wages, cutting the number of civil servants, reducing spending on social programmes, just like the economic plans of Laval1 or Brüning.2

MEDIAPART: What would be some ways to get out of the crisis, if this European political power existed?

A.O.: First we need to understand that we won't get out of the crisis if we consider that the rights of creditors are untouchable. That is untenable and leads to a dizzying rise in debt, as the Irish case showed. Wage earners cannot continue to pay the high revenues of financiers. We need a 'New Deal'.

MEDIAPART: Does that mean that public debts must be renegotiated ?

A.O.: That would be an important step. But it is linked to the previous point: there must be a captain on board the ship. In order to renegotiate debts, one has to be able to speak to creditors with a single voice. It's the only option to free ourselves from the tyranny of the markets, and to put an end to excessive interest rates on debt.

It should be noted that the high interest rates that some European countries are paying on their debt is an example of European dysfunction. In theory, high interest rates serve to compensate the lender from the risk of insolvency. They provide creditors with additional revenues in case of losses incurred through default. But Europe is making debtor countries pay high rates while at the same time guaranteeing the debt.

This is totally contradictory: either the debt is guaranteed in which case the interest rates should fall or it is not guaranteed and default or restructuring are taken into account. Unless high rates are part of yet another option. Perhaps high rates are conceived as punishments, which brings us straight back to the total lack of European solidarity.

The idea of imposing the notion of European debt is often mooted. There would no longer be an Irish debt or a German debt, just a global European debt. But this solution can only succeed within the framework of a global negotiation aimed at reducing our extreme dependence on the markets. That's the central issue.

--------------------------

1: Pierre Laval was president of the French council of ministers (a post equivalent of today's prime minister) four times during the 3rd Republic between the two world wars.

2: Heinrich Brüning was German Chancellor from 1930-1932 during the Weimar Republic.

'Pulling out of the euro would only increase the pressure'

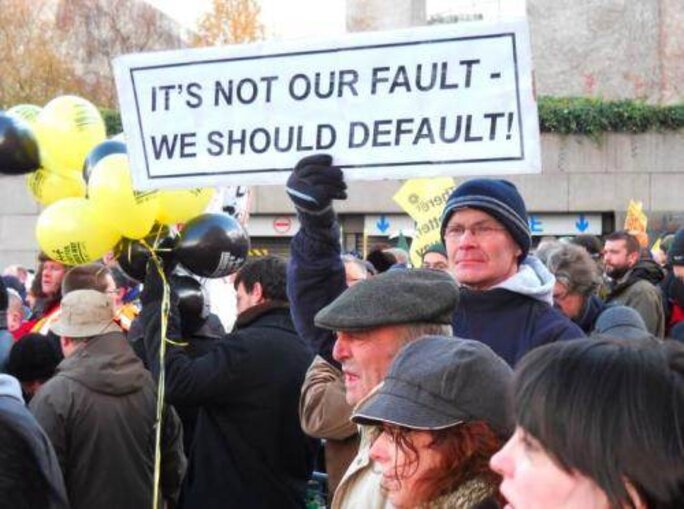

MEDIAPART: Wouldn't Ireland or Portugal be better off defaulting rather than accepting the Brussels or International Monetary Fund schemes?

A.O.: Please note that there are many ways to manage debt. Regarding Ireland, one concrete option is to lift State guarantees on bank bonds. Then decide that the creditors of those banks also have a responsibility and that their claim settlements will be capped. Depreciation of private debt is not uncommon, not to say intrinsic to the workings of the financial machine.

This brings us back to my earlier point. It would be mad to try to guarantee all of the credits. That would necessarily imply the transfer of tax revenue to the financial sector and that is fundamentally counterproductive - and unfair. It must be noted that the levels of public debt that have built up today are the direct consequence of dysfunctional financial and banking systems.

As for dealing with public debt, there are many possible paths including influencing interest rates, influencing repayments, playing a role in determining the payment deadline, and cost of the debt. In fact, there are many instruments available. However, all of these actions require a structured political policy. Denying access to international funds is a weapon, when in the hands of the markets, whose power must not be underestimated.

MEDIAPART: What if the 'small' states left the euro zone?

A.O.: That is technically possible. Whether that's the solution, I don't think so. One could argue that had they not joined the euro zone these countries might not be facing their current problems, more specifically they would have been able to adjust the parity of their currencies. But now that they're in, opting out would probably add to their woes more than anything. Once out of the euro zone, these countries would have a hard time obtaining credit. Pulling out would just increase the demands made by financial markets.

MEDIAPART: Are there any reasons to be optimistic?

A.O.: It's become clear over the past few years that reality can be a demanding task master. It managed to impose rapid and unexpected ideological shifts. In particular at the European Central Bank. Now [since spring], the ECB is buying back sovereign debt, something that was inconceivable just a year ago. From the standpoint of monetary doctrine, this is a radical change from the euro's founding myth of a single currency conceived purely as an economic instrument, free of political influence.

I believe that the ECB should continue down that path. A strong European political entity, willing to shed its state of dependence on international finance, would find the single currency to be a powerful force. Finally, regarding ideological changes imposed by necessity, one should keep in mind that at the time of the Greek crisis, the Germans were opposed to the idea of a European bailout for the indebted countries. Reality left them little choice.

-------------------------

English version: Patricia Brett