The April 22nd first round of the French presidential elections left incumbent candidate Nicolas Sarkozy in a close second-place behind the Socialist Party’s François Hollande. In his campaigning before the final play-off between the two on May 6th, Sarkozy has caused controversy and dismay over his overt attempts to capture the electorate of the far-right Front National party, whose candidate Marine Le Pen scored almost 18% in the first round poll. While the outgoing president has placed immigration issues to the fore, he also announced plans to organise a rally in Paris on May 1st to honour what he deems to be "real labour", as a counter-demonstration against the traditional trades union-organised May Day parade. The initiative is an outrageous throwback to the WWII collaborationist Vichy government of German-occupied France, writes Mediapart economic and social affairs correspondent Laurent Mauduit, who recalls the attempt in 1941 to transform this day of international workers’ solidarity into a day in honour of so-called "labour and social harmony".

-------------------------

In his madcap escapade to capture far-right voters and to transform his ruling conservative party, the UMP, into an extreme-right-wing party, Nicolas Sarkozy has now stepped across a line. It is a symbolic line, but a highly revealing one, because he has dreamed up a May Day celebration that closely resembles that conceived in other times by Marshal Philippe Pétain, head of the collaborationist Vichy government during the WWII occupation of France by Germany.

That the line has been crossed is clear from Sarkozy’s comments and by the controversy they created. A quick recap of events allows to better discern ulterior motives. The verbal jousting began on the morning of Monday April 23rd, the day after the first round of the presidential election. Leaving his campaign headquarters, Sarkozy announced to journalists that he intended to organise a May Day for "real labour". His spokeswoman, Nathalie Kosciusko-Morizet, following on his heels, announced that it could take the form of an outdoor rally in Paris, at the Trocadero square, for example.

During a campaign meeting just a few hours later in Saint-Cyr-sur-Loire, a suburb of Tours, Sarkozy attempted to explain his notion of "real labour" and the people it represents. "It is he who has built something his entire life without asking anything of anyone," he said, "who gets up very early every morning and goes to bed late at night, who doesn't ask for congratulations, nor medals, nothing. It is he who started at the bottom and hitched himself up as high as possible and tells himself, 'I want my children to live better than I do and to start out higher than me.' Real labour is he who says 'oh, I don't have great wealth but the wealth I do have means a lot to me because it represents so much sweat, so many thousands and thousands of hours of work, so much pain, so many sacrifices, so much suffering, that wealth will not be stolen from me. I worked hard for that wealth and I have no intention of making apologies for having built this life'. That's real labour. [...] It is he who says 'all my life I have worked, I paid my taxes, I didn't defraud the state, and when it is time to die, I want to leave everything I have built to my children without the State coming in and helping itself'."

The tone was set by he who has the gall to present himself, yet again, as the candidate of the people and of the lowly, he who, for five years, showered his rich supporters with gifts, he who has the nerve to disguise himself as an anti-establishment candidate when one of his political advisors is the so-very establishment business executive Alain Minc. Sarkozy’s rhetoric was deliberately close to that of the leader of the far-right Front National party, Marine Le Pen. Through allusion, Sarkozy also implies that France is a country of slackers. If he is issuing a call to the lifeblood of the nation, if he talks directly to the people, it is because the country is pulled down by the trade unions, he insinuates.

Sarkozy's allies have lost their republican benchmarks

In short, Nicolas Sarkozy will organise "his" May Day – in contrast with the May Day of the shirkers, of workplace union representatives and of trade union staffers.

On Tuesday, April 24th, interviewed on radio station France Inter, the president’s senior advisor, Henri Guaino, continued the attack in the same populist vein. "We have got used to seeing May Day parades with only union staffers," he deplored. "Do you mean we will have two parades, one for the workers and one for the slackers?" the journalist asked. "No, there will be the parade of the union staffers and a parade of workers," Guaino repeated. Those words reflect an earlier theme adopted by Sarkozy a few weeks earlier, launching a battle against what he calls the "intermediary bodies" - by which he means trade unions. One day he attacked the CGT, a major trade union confederation, the following the CFDT, another confederation, and accuses them of "getting involved in politics" rather than "defending the interests of the workforce".

Following the first-round results, Socialist Party candidate François Hollande was rightly indignant regarding Sarkozy's antisocial, populist and anti-union campaign aimed at picking-up far-right votes. He was also indignant at the type of counter-demonstration envisaged: a face-off between the workers and their unions. "That would mean that there is a false labour in France, that there is an opposition to be organised between workers themselves, or between the employed and the unemployed or between the employed and those on benefits?” Hollande asked speaking at a campaign rally in Lorient in Brittany on April 23rd. “No. If May Day was created it was because there were men and women who wanted to unite together."

The answer was clear, but Holland could have gone further. For this desire of Sarkozy's to organize a May Day for "real labour" draws on historic roots with which he is familiar.

Originally, May Day was not a celebration of labour, but of workers. It is the day of the oppressed against the oppressors. It is a grand show of unity among the workers across the world. The very fact of having to recall the roots of the international workers' movement demonstrates that the Sarkozy-led conservatives have lost all of their republican benchmarks.

On June 20th, 1889, the second congress of the Second International of Socialist and Labour Parties approved the principle of holding a day of worker mobilisation and international solidarity. It suggested it be held annually on May Day in commemoration of the 1886 Chicago Haymarket massacre. Strikes and demonstrations in favour of an eight-hour work day, over a ten-day period in the spring of 1886, were particularly successful in Chicago but were also brutally repressed by the police. During a strike on May 4, dynamite was thrown at the police and shooting broke out, eight police officers died as did at least four strikers,while about 80 people were injured. The police held eight strike leaders responsible. They were tried, found guilty and were hanged.

Does Henri Guaino, who scoffs at union staffers demonstrating on May Day, need to be reminded of the names of the martyrs who died in Chicago? They included new arrivals to the United States, just off the boat from Europe. Their names – and it is they whose memory is commemorated on May Day – are August Spies, born in Hesse, Germany in 1846; Samuel Fielden, a British national born in 1846; Oscar Neebe, born in the USA in 1846; Michael Schwab, born in Mannheim, Germany, in 1853; Louis Lingg, born in Germany, in 1864; Adolph Fischer, born in Germany 1856; Georges Engel, born in Germany in 1835; Albert Parsons, American, born in 1847.

A deliberate reference to France's darkest hours

On May Day 1891, in Fourmies, in northern France, a peaceful demonstration by textile workers, also calling for an eight-hour work day, ended in a bloodbath when the army shot at the crowd, killing ten. The outcry caused by this event rooted the Second International's May Day proposal in the traditions of the European Left.

Since then, only a single regime has attempted to sweep away this tradition - that of Marshal Pétain, who wanted to break with the idea of workers' unity to create a day celebrating labour. Not "real" labour but almost, as pointed out by Jean-Claude Mailly, leader of trade union confederation Force Ouvrière, speaking last week on radio station France Info.

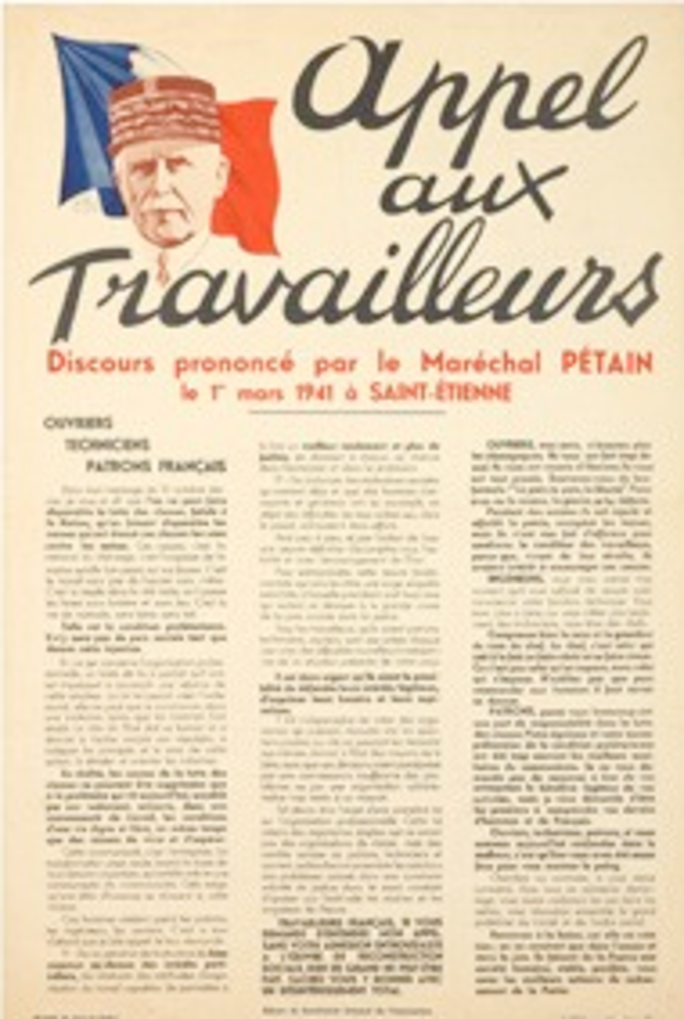

On May Day 1941, in the city of Saint Etienne, Pétain first made a speech addressed to "French workers, technicians and employers," which rejected the class struggle and promoted defending the common good and the creation of social committees. A poster was created to report the speech (see above left). Then on April 24th of the same year, Pétain officially proclaimed May Day as a "day for labour and social harmony". The red wild rose, dear to the Left, was replaced by the now ubiquitous lily of the valley.

The history, glorious and cruel, of workers' struggles of the late 19th century, and the shameful history of Vichy, is of course familiar to Nicolas Sarkozy. These allusions must thus be taken for what they are – a strong and deliberate reference to France's darkest hours.

"For the first time in ages, we have heard comments from the mouth of a serving president that are overtly Pétain-ist,” declared Jean-François Kahn, a veteran French newspaper and magazine editor and now an active supporter of the centrist MoDem party, in a communiqué released last week. “Whatever one may think of [François Hollande], hesitation is no longer possible, no longer tolerable,” continued Kahn, calling for an anti-Sarkozy vote in the final round of the presidential elections next Sunday. “All republicans, all democrats who, out of patriotism, reject the civil war rhetoric and the laceration of our common nation, whether they claim the legacy of [Jean] Jaurès, of [Georges] Clemenceau, of [Charles] De Gaulle, of [Pierre] Mendes France or of Robert Schuman, must vote to bar the road to the sorcerer's apprentice so that we can turn the page."

- Laurent Mauduit is one of Mediapart's specialist writers on economics, finance and social affairs. Previously economics editor of French daily Libération, and a senior economics journalist and editorialist with Le Monde, he is a co-founder of Mediapart.

-------------------------

English version: Patricia Brett

(Editing by Graham Tearse)