It was the biggest rout in the history of the CAC 40. On October 25th 2023, Worldline, the number two European provider of payment solutions for businesses, revised its earnings forecast downwards. The share price collapsed by 59% in a single day. And the group was thrown out of the well-known French stock market index.

Behind this collapse lies one of the biggest financial scandals Europe has ever seen. For ten years, the French group Worldline processed, with complete impunity, billions of euros in fraudulent or unethical payments on behalf of the worst actors in e-commerce: online swindlers, illegal casinos, controversial pornography groups and prostitution websites.

This is what has been revealed by the 'Dirty Payments' investigations, led by Mediapart and twenty other international media outlets coordinated by the European Investigative Collaborations (EIC) network, based on confidential documents and data from Worldline obtained by the EIC. For the first time, the structural flaws and the wall of silence in the payments industry are laid bare.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Fewer than three days after these revelations were first published, prosecutors in Belgium announced the opening of an “investigation on the grounds of money laundering concerning the company Worldline”.

“The company is suspected of processing payments on behalf of businesses engaged in illegal activities, where anti-money laundering regulations may not have been respected,” added the Brussels prosecutor’s office. The case has been entrusted to the federal police and “concerns the Belgian entity of the Worldline group”, based in the northern suburbs of Brussels.

When contacted, the Worldline group said it had “taken note” of the launch of the criminal investigation and that it will “cooperate with the authorities”.

Little known to the public, Worldline is nonetheless a key player in the European economy, handling 500 billion euros in card transactions each year, whether through shops or online.

The EIC investigation reveals that the group, in breach of its regulatory obligations, knowingly turned a blind eye to the fraudulent practices of its “high-risk” clients (involved with sex, casinos, digital goods and services, and so on), who were especially exposed to the risk of fraud and money laundering.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

At the helm of Worldline was the very cream of the French elite. Former economy minister Thierry Breton chaired the board until his appointment as European commissioner in 2019. He chose as its operations boss Gilles Grapinet, a graduate from the elite École nationale d'administration and a member of France's prestigious tax inspectorate who had been his chief of staff at the French Finance Ministry.

To boost profits and the share price, the bosses banked on shady websites that offered extraordinary returns, without a thought for the thousands of victims tricked in France and around the world, or for the kind of trade they were encouraging.

To explain: a standard online trader generally pays less than 5% in commission on each payment to the operator handling its transactions. At Worldline, more than 580 e-merchants identified in the 'Dirty Payments' investigation were paying more than 5% in commission, and at least 350 of them more than 10%. This is a reliable marker of fraud, behind which lay a vast scandal.

When contacted by the EIC, Worldline declined to comment on the facts reported in the investigation. It explained: “As a listed company, Worldline may not communicate to third parties, including journalists, confidential information on a selective basis. In addition, Worldline may not comment on individual past or current customers’ situations.”

It added: “Worldline is committed to the best standards in terms of compliance and prevention of financial crime and has reinforced its resources in that respect.” (See its full response in the appendix.)

The American fraudster

Hived off from the tech group Atos in 2014, from the start Worldline set up a department within its Belgian branch to attract high-risk merchants. One of the very first was a shady United States citizen, recently deceased, nicknamed the “porn baron”: Ray Akhavan.

By mid-2014, under the chairmanship of Thierry Breton, the group was already handling payments for more than 250 of Akhavan’s porn sites, even though his business relied on some ingenious financial setups and the so-called “subscription trap”: with adverts which hold out the promise of free access, while the monthly charge is tucked away in the small print.

In 2019, as the US justice system launched a probe into him over a fraud scheme to hide online cannabis sales, which led to his arrest in 2020 and a 30-month prison sentence in 2021, Akhavan tried to shield himself by hiding assets in a trust. In a Telegram message, one of his men said this should remain “discreet”, but added they ought to tell Worldline because “with the people that are close to us, we should be honest”.

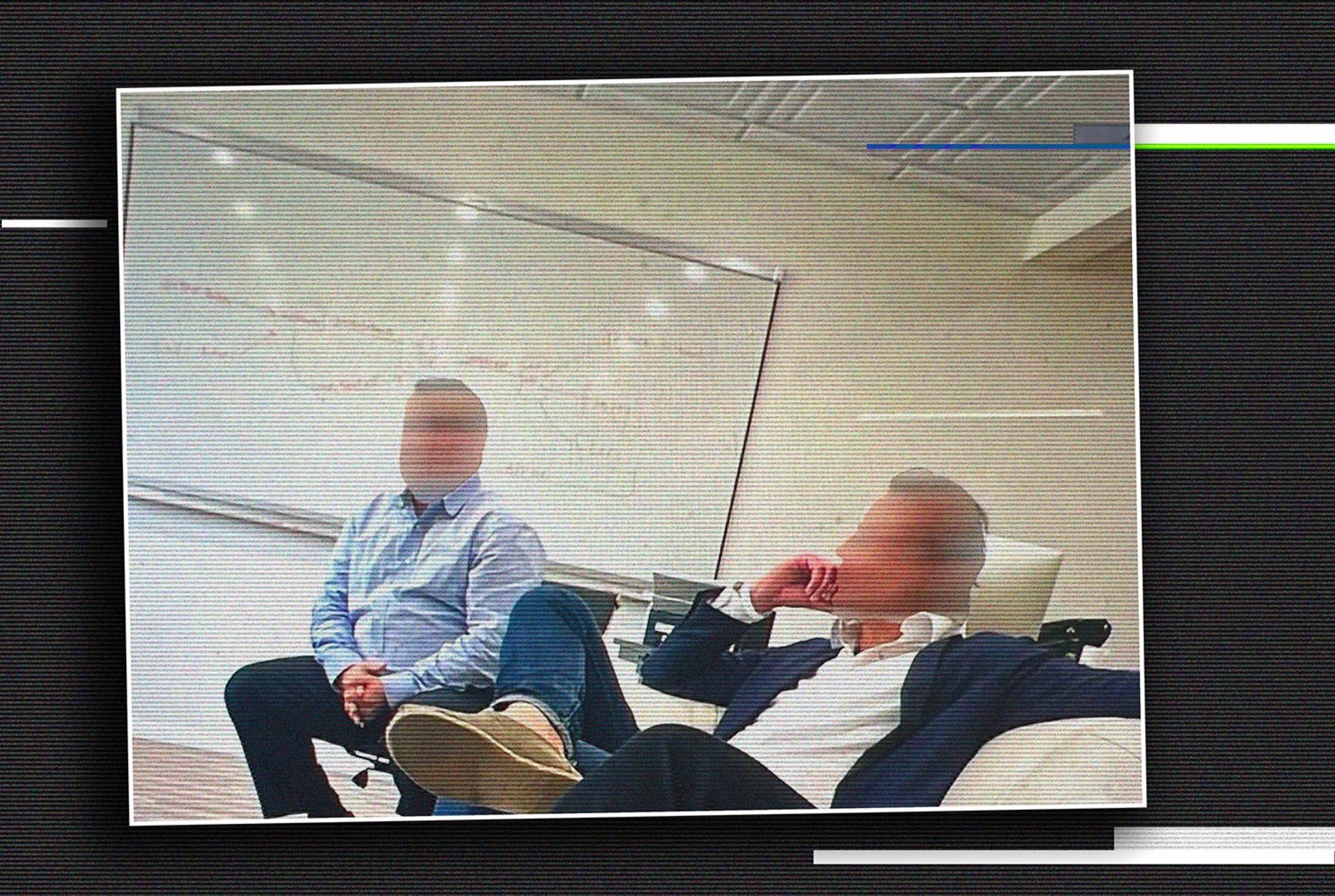

Enlargement : Illustration 3

The previous year, Akhavan and three of his close aides had hosted a Worldline salesman in California to talk business. It was a surreal scene: a chart of the cannabis scam was shown in large print on the wall (see photo above), and two of those present shared an intravenous injection - of “vitamins”, they said.

Approached by Mediapart, Thierry Breton said that right until he left Worldline in 2019, neither he nor the board had “any knowledge whatsoever of the facts” we put to him (see his full response in the appendix).

The agent

Ray Akhavan was introduced to Worldline by emerchantpay (EMP), a British firm that acts as an agent, in this case acting as a provider of high-risk merchants. EMP was the very first partner of the special department created in Brussels in 2014 to handle this sensitive business.

By 2020, this service had more than 3,000 clients, many of them problematic sites specialising in online scams.

In March 2020, the rate of fraudulent payments handled by Worldline hit 1.5%. That is twice the upper limit set by card company Visa, which launched an investigation. Visa - like its rivals - imposes strict fraud caps, and if they are breached it can hand out fines or even strip operators of the right to handle payments with its cards. For Worldline, that would spell financial death.

The French group then decided to shut down only the dirtiest merchant accounts, those with fraud rates above 15%, “with the exception of” those brought in by its British agent EMP. The group asked “eMerchantPay to help us with cleaner transactions” but this was turned down.

So, in order to “decrease the fraud ratio” of Worldline Belgium, hundreds of dubious merchants were moved to a subsidiary in Sweden, though they continued to be managed covertly from Brussels.

In 2021, an internal audit that was sent to Worldline CEO Gilles Grapinet flagged shortcomings in compliance within the Belgian “high risk” department. Yet soon after, its founder and head was promoted to head of e-commerce for the whole group.

Worldline even raised the fraud thresholds to very high levels: now, 20% of an online trader’s payments had to be fraudulent for it to be dropped, up from 15% before.

When contacted, emerchantpay said in a statement released after the publication of the EIC investigation: “We are aware of recent media allegations relating to the processing of transactions for online merchants, to which emerchantpay Ltd has been linked, and which we believe fundamentally misrepresent the facts.

“We take such matters extremely seriously. We have initiated an internal review to understand the full context of the claims to ensure we respond appropriately.”

It added: “We have always operated – and continue to operate - in full compliance with all applicable laws.” (Read the full statement in the appendix.)

Illegal casinos

Meanwhile, Worldline doubled down on its approach. In June 2021 the group's leadership launched a plan called 'Spark', with an outrageous target: to double turnover in four years. To reach that goal, the plan leaned heavily on high-risk merchants in general, and online casinos in particular.

Yet the group had serious compliance issues in this area. An internal document from March 2021 shows that in December 2020 alone, it handled over 5 million euros in card payments (that is, by players) for online casinos from six countries. These included France, where such casinos are completely banned.

Worldline’s bosses nonetheless made considerable efforts marketing a risky new tool, developed by one of their Swedish offshoots, which they hoped would be a money-spinner.

This software, named Payment IQ (PIQ), is also sold under the brand 'Worldline Payment Orchestration'. It was designed specifically to help online casinos beat payment refusals. When a player wants to top up their account with their bank card, PIQ can try the same payment with up to 250 payment operators in a row, which considerably increases the chance of it being accepted.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

This tech is a gift for illegal casinos, who use it a great deal thanks to Worldline. One major client is Soft2bet, a casino group based in Malta and Cyprus with a Comorian gambling licence that, in theory, bars it from operating in Europe. A recent investigation by the journalist collective Investigate Europe found that Soft2bet runs 140 gambling sites, 114 of which were blacklisted in at least one EU country as of February 2025.

Our investigation found that more than thirty online casinos linked to Soft2bet use Worldline’s PIQ tool for payments, and that they accept French players - illegally.

That is no surprise, given the damning findings of an internal audit in March 2024. It found that Worldline’s Swedish offshoot in charge of PIQ was “unaware of their legal compliance obligations” and carried out no checks on its clients; “contract signature” was carried out “without any basic document checks”, while after deals were signed there was “no client monitoring”. Worldline’s anti-financial crime unit ordered a reappraisal of all clients.

The results seem to have been underwhelming, as Soft2bet was still using Payment IQ a year later. Even more worrying, this system has now become huge, handling payments worth 12 billion euros a year. Since 2021, Worldline has stopped limiting it to casinos and opened it to other high-risk traders, such as cryptocurrency platforms.

Porn empire

Worldline has not publicised the fact, but the group has also made a fortune from porn sites, including the most controversial ones.

The top client of the “high risk” department by far is Onlyfans. This hugely successful site lets “creators” sell content, mainly sexual, while skimming off a cut. Worldline handles much of Onlyfans’ payments and huge sums are involved: over 3 billion euros in the past two years, which earned the French group more than 100 million euros in net income.

But Onlyfans is regularly accused of hosting videos of women who have been filmed without their knowledge, exploited or raped. More than 120 victims have filed complaints in the United States alone, as revealed by Reuters news agency.

Following such cases, in 2022 and again in 2023, Visa launched probes into Worldline and ordered the French group to prove, or risk fines, that Onlyfans’ control procedures were strong enough to stop the use of illegal content. Worldline chose to stick with its cash cow.

The same happened with many other porn operators under investigation in Europe. For instance, it happened with the Swiss company run by Marc Dorcel, despite being suspected by the French tax authorities of using that structure to dodge taxes. There is also the example of the website Jacquie & Michel, named in a wide-ranging criminal case over alleged rape and human trafficking.

Over the past two years, Worldline has also handled more than 20 million euros in payments for the porn giant WGCZ, owned by Frenchman Stéphane Pacaud. Half of this was for his site Analvids.com (formerly Legal Porno), whose extremely violent filming methods were made public by victimised actresses. Worldline continued to work with the firm.

The French payments giant also works for a Canadian group (Gamma Entertainment) active in the so-called 'fakecest' niche: one of its sites shows videos with plotlines involving sexual acts within families, such as between a young girl and her “stepfather” - the word “step” being used to avoid charges of promoting incest.

Sites linked to prostitution

The 'Dirty Payments' investigation also shows that Worldline has worked with at least ten websites linked to prostitution, despite the company’s own internal rules forbidding such activity outright.

Until June 2024, Worldline processed at least 20 million euros in payments for Secret Benefits, a website that invites young women to become “sugar babies”, meaning they are paid or supported by older, wealthy men old enough to be their fathers (“sugar daddies”).

Worldline also continues to count as a client a Swiss company owned by German and Russian businessmen, which runs a prostitution site aimed at the Austrian market. Most prostitutes in Austria are foreign women under the grip of trafficking networks.

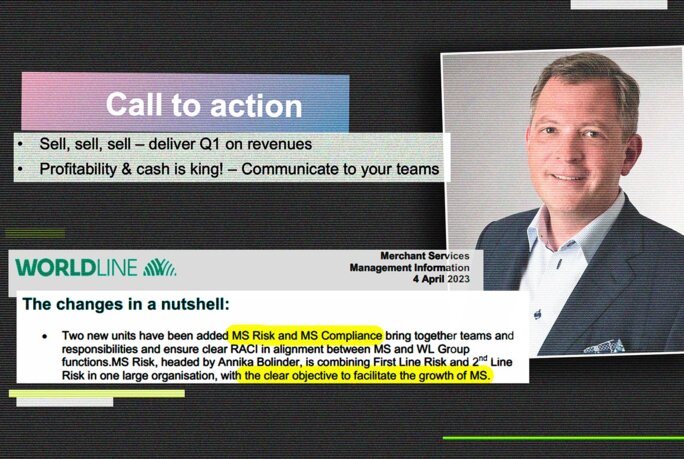

Sell, sell, sell… profitability and cash is king!

As we reveal in another part of this series of investigations, the French group has also handled payments for several prostitution sites, including one of the largest in France, controlled by an individual convicted of pimping.

It may seem astonishing that a publicly-listed company, which joined France's prestigious CAC 40 stock market index in 2019, would take the risk of getting involved in such a trade. Under French law, the offence of pimping, which carries a prison sentence of up to seven years, is defined very broadly. It includes “assisting” the prostitution of others or “benefiting from it”, “in any way whatsoever”.

The German connection

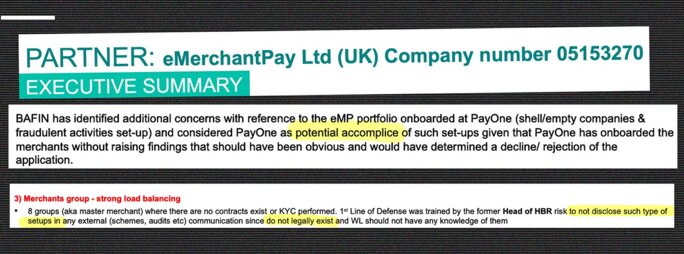

In 2020, Worldline bought a rival and its German subsidiary, PAYONE. A year later, two audits criticised PAYONE’s compliance record: the German firm had worked with 311 suspect merchants brought in by an associate of Ray Akhavan, the so-called “porn king”, who was convicted alongside him in the United States in a cannabis transaction fraud case.

In the wake of the audits, major German bank Commerzbank cut ties with PAYONE in several countries and for various high-risk activities, citing “inadequate oversight” internally, with only “1-2 employees for AML/CTF transaction monitoring” [editor's note, AML/CTF = anti money laundering/countering the financing of terrorism] despite “massive transaction volume”.

In Paris, Worldline boss Gilles Grapinet appeared unconcerned. No wonder: the dubious clients of the German arm were extremely profitable. Despite the scandals, in September 2022 PAYONE boss Niklaus Santschi was promoted to head of Worldline’s “merchant services” division, which accounts for 80% of the group’s income.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

“Sell, sell, sell… profitability and cash is king!” the Swiss manager wrote to his team in March 2023. He also worked to weaken the “risk” department, which was now given the “clear objective to facilitate the growth” rather than hold it back. Around ten experienced staff tasked with fighting fraud were sidelined, pushed aside or eventually left the company.

In June 2023, an internal document gave a damning picture of Worldline’s anti-money laundering efforts. Checks on new clients were “not compliant” and most monitoring tools were “ineffective”.

The sanction and the crash

These failures in tackling fraud began to become apparent, and not only internally, in the form of alarming but “confidential” briefings. Several banks stopped working with Worldline, including French bank Société Générale, due to its “limited trust” in the group. Rather than reassess matters, the leadership asked executives to seek out banks with a “risk appetite” that matched Worldline’s dubious clients.

Meanwhile three events would soon halt this headlong rush by the group.

In April 2023, Visa’s anti-money laundering division launched an investigation into Worldline after spotting 76 million euros in suspicious transactions possibly tied to fraud and scams.

In the UK, the auditor of emerchantpay (EMP), Worldline’s favoured agent, resigned citing potential “breach of applicable laws and regulations”. Worldline commissioned an audit, shared with a handful of executives in June 2023.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

The findings were devastating: most of the clients brought in by EMP were shell firms based in the UK and Cyprus, running over 1,700 websites mainly designed to fleece internet users. It was so “obvious” that PAYONE, Worldline’s German subsidiary, was seen by the local regulator as a “potential accomplice”.

Even worse was that the bulk of these merchants, officially independent, were in fact controlled by a handful of underground networks known as Linkmedia/Aether or iMerchant/Eureka [see our investigation, in French]. Worldline knew this, yet ordered staff in the “risk” department to hide it from Visa, Mastercard and regulators, as those networks did “not legally exist and Worldline should not have any knowledge of them”.

In July 2023 the German regulator BaFin sanctioned PAYONE for breaching its anti-fraud and anti-money laundering obligations. Worldline’s German arm was forced to drop more than 450 high-risk clients and barred from taking on new ones.

Yet more than 400 of these clients, deemed off-limits by BaFin, quietly carried on their business for at least seven months through other parts of the group, especially in Belgium.

Nonetheless, this sanction by the German regulator sparked panic at Worldline’s headquarters in La Défense, the business district west of Paris. A clean-up plan for high-risk clients managed in Brussels, codenamed “Atomic and Odin”, was set in motion.

According to confidential internal data from 2023, the 1,300 dirtiest clients, eventually dropped in Germany and Belgium, carried out at least 800 million euros in transactions over the previous year. One can thus reasonably infer that Worldline has facilitated billions of euros in suspect payments since 2014.

Among these same e-merchants, the rate of transactions flagged as fraudulent by clients to their banks was huge: it topped 10% for 550 merchants, and even 15% for 150 of them, according to our confidential information.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

Worldline declined to comment on these figures but insisted that “by nature”, merchants classified as high-risk “exhibit elevated chargeback [editor's note, a process under which unhappy customers can be reimbursed by their bank] and refund ratios due to customer behaviors and business model structure”.

These dubious merchants were so profitable that their departure dented earnings. As we have seen, on October 25th 2023, the group had to issue a profit warning, sending its share price plummeting. Staff then paid the price when a cost-cutting plan proposed 1,400 job losses, including 330 in France.

Two top executives were eventually fired in 2024: former PAYONE boss Niklaus Santschi in February, and Worldline CEO Gilles Grapinet in September. Other senior figures behind the fraudulent payment system remain in post.

The endless crisis

Officially, since 2024, all is now in order at Worldline. Asked by the EIC, the group says its “fraud ratio is below the industry average”.

But our 'Dirty Payments' investigation has uncovered several highly suspect merchants still on Worldline’s books, including illegal casinos, prostitution-linked websites and fake dating sites. And there are also porn giants such as OnlyFans, on whom Worldline remains heavily financially reliant.

The group’s high-risk activity remains vast: internal data from 2025 shows the French group processed 12 billion euros in payments in this sector over the past year, including 3 billion euros for gambling sites and 2 billion euros in the “adult” sector.

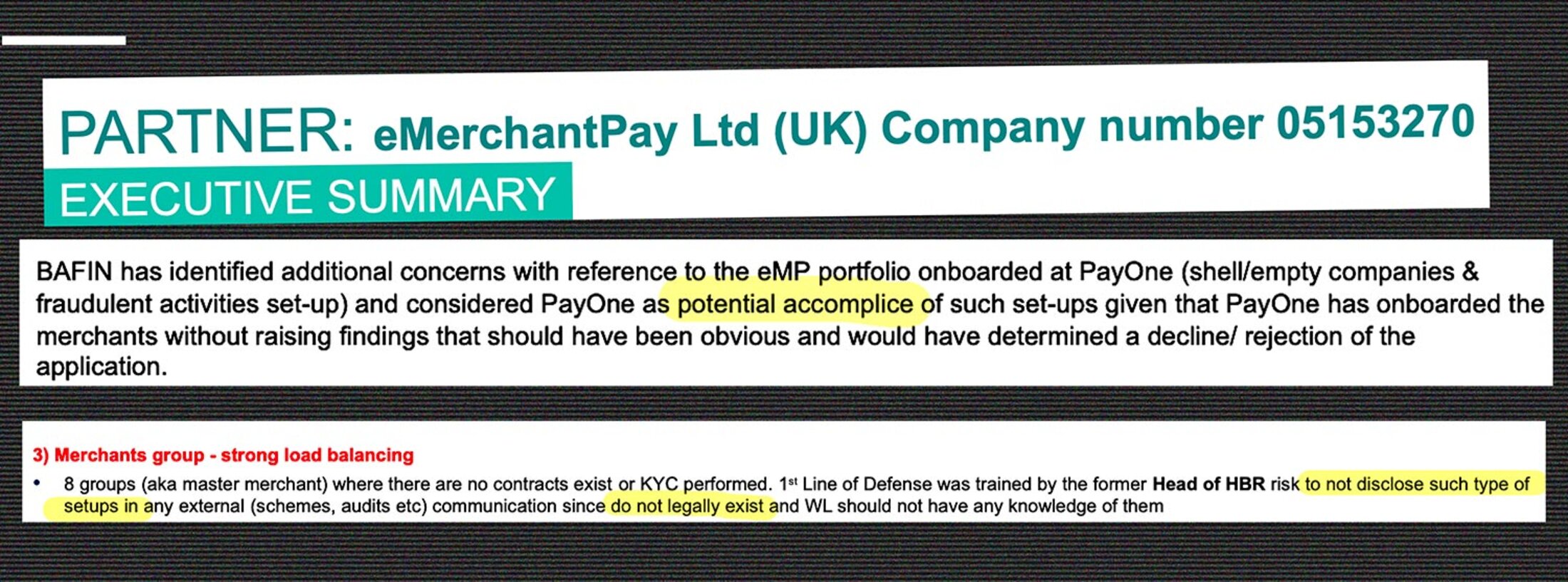

Despite the huge issues with fraud prevention, the leadership decided as part of the cost-cutting plan to axe dozens of roles across Europe in the “risk” division, known internally as “RMO”. The French payment champion even considered outsourcing most of this work to India, before switching to Poland after trade union protests (see document below).

Enlargement : Illustration 8

“Worldline is committed to the best standards in terms of compliance and prevention of financial crime and has reinforced its resources in that respect,” the group told us.

Yet an internal audit presented to senior management in April 2024 showed customer screening and anti-money laundering checks still remained inadequate. A major overhaul is under way in most countries but even if all goes to plan this will not be completed until 2026.

A sign of the seriousness of the situation is that two years after the first injunctions issued by BaFin in 2023 against PAYONE, the procedure is still ongoing and compliance problems are still unresolved. According to our information, inspections have also been launched by regulators in Belgium and the Netherlands. But with European regulators slow to act, no real sanction - a fine for instance - has yet been imposed, either on Worldline or its executives.

Worldline is also legally bound to report dubious clients to anti-money laundering agencies in countries where it operates, such as TRACFIN in France. Has it done so? The group declined to tell us. Our investigation has nonetheless found that several scam masterminds dropped by Worldline last year are still fleecing internet users to this day.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this investigation can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter