It is the worst-off in French society who have paid the heaviest price for the financial crisis. That is the main finding of the 2016 report by the official statistical agency the Institut National de la Statistique et des Études Économiques (INSEE) on “Household incomes and capital”, published on June 28th. Though the figures are not surprising they are nonetheless alarming: during the five years from 2008 to 2013, the years in which the effects of the world financial crisis were greatest, the median standard of living of French people fell on average by 0.2% a year or 1.1% in total. This fall, says the report, is “unprecedented” since such studies began in 1996. Indeed, for the bottom 10% of households income fell by 3.5% over that period. In other words, the financial crisis greatly increased inequalities. INSEE also highlights trends in poverty levels, talking about an “unprecedented worsening in France”.

The annual INSEE study usually elicits some frustration, as the figures it is based on are always three years old. This is because in order to get the clearest picture of changes in French household incomes and capital the official statistical agency has to collate tax returns, the most reliable source of data. As a result the annual study never gives the most recent trends. Yet this latest report, based on figures to the end of 2013, nonetheless has even greater than usual interest as it allows us to see the trends in these inequalities during the years when the financial crisis was at its worst, from 2008 to 2013.

Here is the INSEE report in full (in French):

The first figures that catch one's attention are the most recent ones. We see that in 2013 the median standard of living of people in mainland France was 20,000 euros a year, or 1,667 euros a month. (Here, 'standard of living' is defined as a household's net income divided by the number of 'units' it contains, with one adult counted as one unit with additional adults and children of 14 or over counting as 0.5 of a unit and younger children as 0.3.) Thus 50% of all French people in that year had a standard of living below this 20,000 euro threshold. This figure alone is itself very striking because it confirms that the median standard of living or income level of French people is very low. To give an indication of this, gross earnings based on a 35-hour-week on the minimum wage in 2016 come to 1,466.62 euros a month, compared with 1,457.52 in 2015. In the light of this figure one can understand the astonishment of French people when they learn that the annual pay of certain big bosses, such as the head of car-makers Renault-Nissan, Carlos Ghosn, can exceed 15 million euros a year.

But as soon as one steps back one can see that the changes over the years covered by the study itself are just as bad. This should come as no surprise as it was ordinary French households who were made to bear the brunt of the financial crisis, first by President Nicolas Sarkozy (2007-2012) then by President François Hollande (2012 to now). The figures show the scale of the social fractures that have been at work during the years of the crisis. Over the five-year period from 2008 to 2013 the median standard of living of French people went down by 1.1%, or 0.2% a year. “This slow decrease of the median standard of living over five years is unprecedented during the observation period of the Tax and Social Income studies from 1996 to 2013,” says INSEE.

In concrete terms, then, the median incomes of French people have fallen from 20,260 euros in 2008 to 20,000 euros in 2013. But the change is even more serious than it appears, as these figures hide the great disparities that exist depending on a person's level of income. If one looks at the bottom 10% in terms of standard of living it is apparent that the drop is considerably more accentuated: income here fell from 11,230 euros a year in 2008 to 10,730 euros in 2013. In other words, the net income of the poorest 10% in French society dropped from 935 euros a month in 2008 to 894 euros a month in 2013.

A damning indictment of economic and social policy

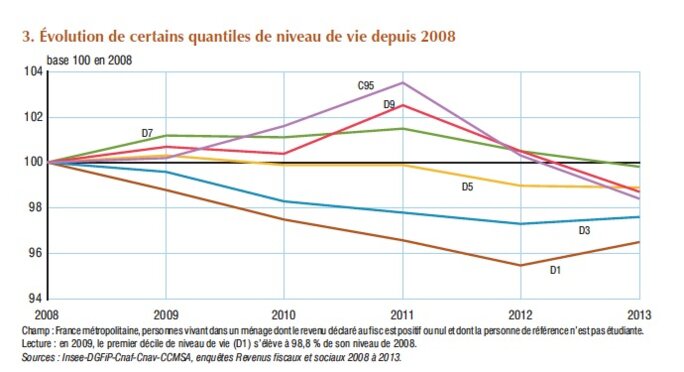

The poorest are not the only ones whose standard of living has been affected by the crisis. The ultra-rich, who own securities, have also, albeit probably temporarily, paid the price but by a lesser proportion. This is what the INSEE report has to say: “Ultimately, in the course of the five years of the small fall in the median income in France, the standard of living of all groups has fallen, with the exception of the eighth decile. The standard of living declines more the lower you are in the list (-3.5% for the first decile to -0.2% for the seventh decile). It goes up at the level of the eighth decile (+1.1%) and decreases clearly for the ninth decile (-1.3%, with -1.6% for the final vingtile).”

For those who want a visual demonstration of this, the INSEE graphic below gives a clear presentation: here one can see the confirmation that the poorest 10% (the D1 decile) are indeed those who have recorded the most worrying change in their level of income. In summary the crisis years were years of strong social suffering but also of a deepening of inequalities, to the detriment in particular of the least well-off.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

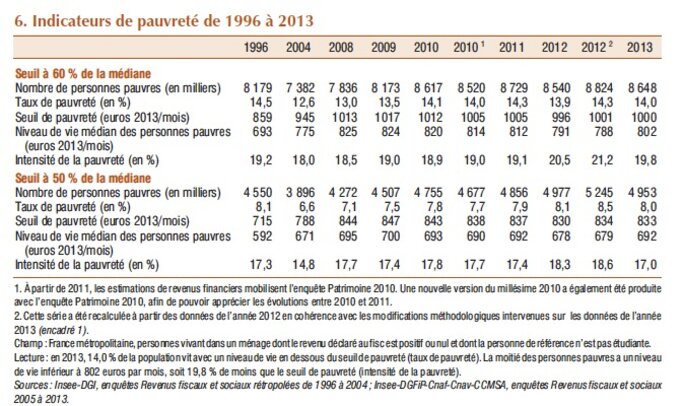

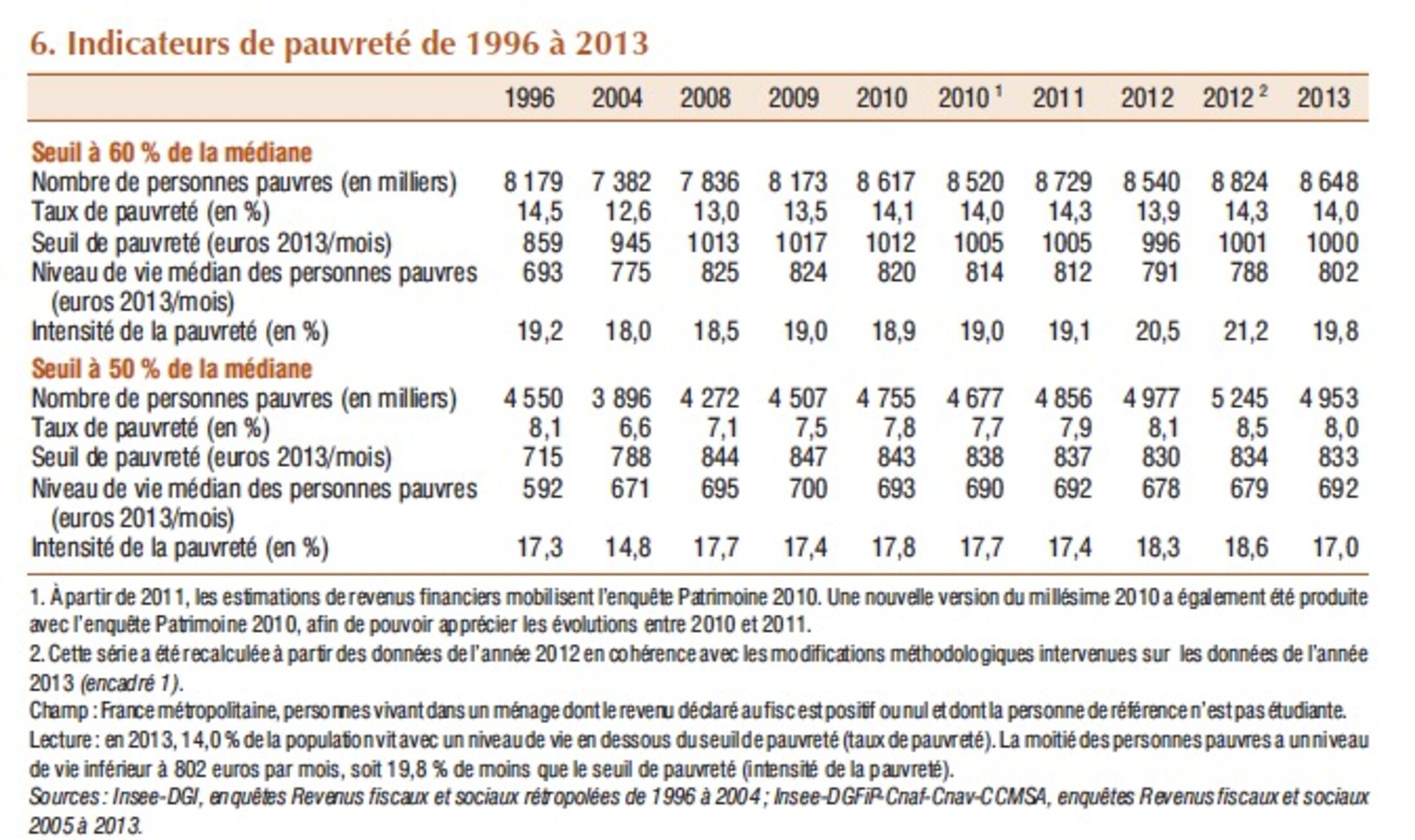

Unfortunately, and to no great surprise, the levels of poverty thus remain exceptionally high. Traditionally INSEE calculates two different indicators of poverty lines or thresholds. Under the first a person is considered to be poor where their standard of living is below 50% of the median income in France; under the second, the threshold is a standard of living under 60% of the median income. It is this second indicator that is most often used in public debate.

Below are the main changes in levels of poverty as shown by INSEE:

Enlargement : Illustration 4

INSEE says that in 2013 “the poverty line, which corresponds to 60% of the population's median standard of living, was put at 1,000 euros a month. Some 8.6 million people are in poverty or 14% of the population. This proportion decreased decreased slightly in 2012 and 2013 (-0.4% then -0.3%), but over the five years poverty increased by 0.7%, going against its previous downwards trend.”

Looking at these figures one could therefore think that the effect of the crisis was indeed to increase the number of poor people, but that this change is simply temporary. Yet it would be very wrong to minimise the seriousness of these figures. For once again INSEE uses a description which grabs the attention, speaking of an “unprecedented” change. It says: “The rate of monetary poverty in 2013 amounts to 14% of the population, in other words a slight fall in relation to that in 2012 (14.3%), continuing the decrease seen between 2011 and 2012 (-0.4%). The rate of poverty clearly increased between 2008 and 2011 (by +1.4%) before falling by 0.7% between 2011 and 2013 in a context where the median standard of living fell by 1% over two years. At the same time, after 2008 the poverty gap [editor's note, measured by INSEE as the relative gap between the median standard of living of poor people and the poverty line] increased by 0.5%, reflecting the deterioration of the situation of the poorest in relation to the rest of the population.”

INSEE then continues its analysis, making the following, devastating, observation: “This worsening of poverty is unprecedented in France. In fact, poverty decreased in an almost continuous manner between 1996 and 2004 (-1.9%). After that it had only fallen in a sporadic manner stabilising (due in particular to the postponement in updating levels of income used to calculate family benefits) around 13% in 2008.”

This indisputable diagnosis is thus a damning indictment of the economic and social policy carried out by Nicolas Sarkozy from 2008 to 2012, that is to say during a part of the period under review in this study. But it is just as damning for François Hollande, and for two reasons. First of all, a part of the period concerned by the INSEE study includes the start of Hollande's term of office from May 2012. Secondly, and most importantly, he has continued and made worse the policies of inequality implemented by his predecessor, increasing handouts to the wealthiest and to companies, refusing any gestures towards the least well-off and increasing the number of reforms that increase flexibility in the workplace. In summary, he did not seek to correct these poverty trends, he made them worse.

Yet what this INSEE study also reveals is the shock-wave of this impoverishment and, in particular, this increase in insecurity in society, which stem from continuing reforms aimed at creating more flexibility that have been carried out for the last 20 years. A final figure bears witness to this: in 2013 “1.9 million people with a job lived below the poverty line, which is 7.6% of employed people”, says INSEE. It goes on to add: “Having a job does not always shield one from poverty.” So, in summary, under this shareholder capitalism a new category of workers has appeared and is growing: that of the “working poor”.

If this comment is true for the year 2013, which is the last year in INSEE's study, then it is more relevant than ever for 2016. One simply has to study the latest statistics on people seeking work. The number of jobseekers in category A, which is the most restricted category (people who have no job and are actively seeking work), may be slightly coming down in the second quarter, but according to forecasters the number of jobseekers in all categories, from A to E, could continue to increase to historic levels, reaching perhaps 6.5 million people.

The INSEE study thus constitutes a very important warning because it shows the worrying nature of the latest trends, which are marked by deepening inequalities. In a second study, covering a much longer period, INSEE makes an observation which confirms the very unequal nature of the capitalism into which France was sucked in the 1980s and 1990s. “The study of standard of living inequality indicators over a long period show some notable variations: after a big drop in the 1970s and 1980s then a period of stability in the 1990s, the inequalities increased during the 2000s,” it writes. But INSEE's work is also important as a warning for the future: with the massive deregulation that France has seen in the workplace, the recovery could quite possibly be accompanied by a massive growth in job insecurity and thus poverty. Thus in a capitalism marked by great social selfishness, a recovery can go hand with a new deepening of inequalities.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter